Defining the Contralto Voice Through the Repertoire of Ralph Vaughan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

A Comparison of the Alto Voice in Early and Modern Opera

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk • w #*>* brought to you by CORE provided.'V by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship... J HUTCHINS A Comparison of the Alio Voice in Early mii Modern Opera j A ' Tw V ill, .^ i%V** i i • i ! 1 i i 4 Music j • 19 15 i • * THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/comparisonofaltoOOhutc COMPARISON OF THE ALTO VOICE IN EARLY AND MODERN OPERA BY MARJORIE HUTCHINS THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1915 , ftfy UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June I 19235. SUPERVISION BY THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY MARJORIS HUTCHIUS, - MODERN ENTITLED A COMPARISON OF THE ALTO VOICE IN EARLY JJffl OPERA, - - FOR THE IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS DEGREE QF BACHELOR OF MUSIC. , Instructor in Charge 1 IG HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF .S • u»uc H^T A COMPARISON OP THE ALTO VOICE IN EARLY AND MODERN OPERA. The alto voice is, in culture and use, as an important solo instrument, comparatively modern. It must be well understood that the alto voice, due to its harmonic relation to the soprano, has always been the secondary voice. The early opera writers, such as Monteverde, Cavalli, Lully, and Scarlatti, although they wrote for this voice when it was sung only by the male artificial con- tralli or counter-tenor, have done much toward putting it where it is today. -

Tippett Stereo Add Set

SRCD.2217 2 CD TIPPETT STEREO ADD SET SIR MICHAEL TIPPETT (1905 - 1998) THE MIDSUMMER MARRIAGE Opera in Three Acts CD1 1 - 15 Act I 61’50” CD 2 1 - 5 Act II (completion) 19’13” 16 - 19 Act II (start) 14’15” (76’07”) 6 - 21 Act III 58’13” (77’27”) (153’34”) Mark, a young man of unknown parentage (tenor) . Alberto Remedios Jenifer, his betrothed, a young girl (soprano) . Joan Carlyle King Fisher, Jenifer's father, a businessman (baritone) . Raimund Herincx Bella, King Fisher's secretary (soprano) . Elizabeth Harwood Jack, Bella's boyfriend, a mechanic (tenor) . .. Stuart Burrows Sosostris, a clairvoyante (contralto) . Helen Watts The Ancients: Priest (He-Ancient) (bass) . Stafford Dean The Ancients: Priestess (She-Ancient) (mezzo) . Elizabeth Bainbridge Half-Tipsy Man (baritone): David Whelan. A Dancing Man (tenor): Andrew Daniels Mark's and Jenifer's friends: Chorus. Strephon, dancer attendant on the Ancients (silent) Chorus & Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (Chorus Master: Douglas Robinson, Conductor's Assistant: David Shaw) Chorus & Orchestra of the The above individual timings will normally include two pauses, one before the beginning and one after the end of each Act. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden P 1971 The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Digital remastering P 1995 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Sir Colin Davis ©1995 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the U.K. Alberto Remedios • Joan Carlyle • Raimund Herincx • Elizabeth Harwood LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita by Wyastone Estate Limited, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK 48 Stuart Burrows • Helen Watts • Stafford1 Dean • Elizabeth Bainbridge CD 1 (76’07”) Act I (61’50”) Act II (start) (14’15”) Make haste, ALL “All things fall and are built again 1 Scene 1 This way! This way! 3’45” Make haste And those that build them again are gay!” To find the way 2 What’s that? Surely music? 1’07” In the dark 3 Scene 2 (leading to:) 0’51” To another day. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

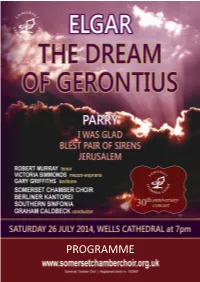

To View the Concert Programme

PROGRAMME Happy birthday Somerset Chamber Choir! Welcome to our 30th birthday party! We are delighted that our very special invited guests, our loyal choir ‘Friends’ and everyone here tonight could join us for this occasion. As if that weren’t enough of a nucleus for a wonderful party, the BERLINER KANTOREI have travelled from Berlin to celebrate with us too ... their ‘return match’ for an excellent time some of us enjoyed singing with them when they hosted us last autumn. This concert comes at the end of a week which their party of singers and supporters have spent staying in and sampling the delights of Somerset; we hope their experience has been a memorable one and we wish them bon voyage for their journey home. Ten years of singing together in the 1970s and 1980s under the inspirational direction of the late W. Robert Tullett, founder conductor of the Somerset Youth Choir, welded a disparate group of young people drawn from schools across Somerset, into a close-knit group of friends who had discovered the huge pleasure of making music together and who developed a passion for choral music that they wanted to share. The Somerset Chamber Choir was founded in 1984 when several members who had become too old to be classed as “youths” left the Youth Choir and, with the approval of Somerset County Council, drew together other like-minded singers from around the County. Blessed with a variety of complementary skills, a small steering group set about developing a balanced choir and appointed a conductor, accompanist and management team. -

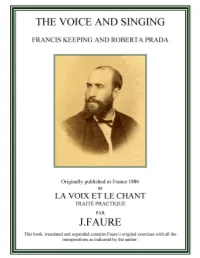

The Voice and Singing Sample Pages.Pdf

2 THE VOICE AND SINGING FRANCIS KEEPING AND ROBERTA PRADA Originally LA VOIX ET LE CHANT TRAITÉ PRACTIQUE J. FAURE PARIS 1886 this book, translated and expanded contains Faure’s original exercises with all the transpositions as indicated by the author. 3 Copyright © 2005 Francis Keeping and Roberta Prada. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2005 by Vox Mentor LLC. For sales please contact: Vox Mentor LLC. 343 East 30th street, 12M. New York, NY. 10016 phone: 212-684-5485 Email: [email protected] Website: www.voxmentor.biz Printed in USA. Awaiting Library of congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ISBN 10: 0-9777823-0-1 Originally La Voix et le Chant, J. Faure, Paris, 1886, AU Menestrel, 2 bis, Rue Vivienne, Henri Heugel. The present volume is set in Times New Roman 12 point, on 28 lb. bright white acid free paper and wire bound for easy opening on the music stand. Page turns have been avoided wherever possible in the exercises, meaning that there are intentional blank spaces throughout. The cover photo of J. Faure as a younger man is from the collection of Bill Ecker of Harmonie Autographs, New York City. The present authors have faithfully translated the words of Faure, taking care to preserve the original intent of the author making changes only where necessary to assist modern readers. The music was written using Sibelius 3 and 4™ software. -

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN's USE of the Passacagt.IA Bernadette De Vilxiers a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Wi

BENJAMIN BRITTEN'S USE OF THE PASSACAGt.IA Bernadette de VilXiers A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Johannesburg 1985 ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) was perhaps the most prolific cooposer of passaca'?' las in the twentieth century. Die present study of his use of tli? passac^.gl ta font is based on thirteen selected -assacaalias which span hin ire rryi:ivc career and include all genre* of his music. The passacaglia? *r- occur i*' the follovxnc works: - Piano Concerto, Op. 13, III - Violin Concerto, Op. 15, III - "Dirge" from Serenade, op. 31 - Peter Grimes, Op. 33, Interlude IV - "Death, be not proud!1' from The Holy Sonnets o f John Donne, Op. 35 - The Rape o f Lucretia, op. 37, n , ii - Albert Herring, Op. 39, III, Threnody - Billy Budd, op. 50, I, iii - The Turn o f the Screw, op . 54, II, viii - Noye '8 Fludde, O p . 59, Storm - "Agnu Dei" from War Requiem, Op. 66 - Syrrvhony forCello and Orchestra, Op. 68, IV - String Quartet no. 3, Op. 94, V The analysis includes a detailed investigation into the type of ostinato themes used, namely their structure (lengUi, contour, characteristic intervals, tonal centre, metre, rhythm, use of sequence, derivation hod of handling the ostinato (variations in length, tone colouJ -< <>e register, ten$>o, degree of audibility) as well as the influence of the ostinato theme on the conqposition as a whole (effect on length, sectionalization). The accompaniment material is then brought under scrutiny b^th from the point of view of its type (thematic, motivic, unrelated counterpoints) and its importance within the overall frarework of the passacaglia. -

A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Research 5-8-2021 The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera Samuel Sherman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/honors Recommended Citation Sherman, Samuel, "The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 47. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/honors/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Northern Colorado Greeley, Colorado The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for Graduation with Honors Distinction and the Degree of Bachelor of Music Samuel W. Sherman School of Music May 2021 Signature Page The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera PREPARED BY: Samuel Sherman APPROVED BY THESIS ADVISOR: _ Brian Luedloff HONORS DEPT LIAISON:_ Dr. Michael Oravitz HONORS DIRECTIOR: Loree Crow RECEIVED BY THE UNIVERSTIY THESIS/CAPSONTE PROJECT COMMITTEE ON: May 8th, 2021 1 Abstract Opera, as an art form and historical vocal practice, continues to be a field where self-expression and the representation of the human experience can be portrayed. However, in contrast to the current societal expansion of diversity and inclusion movements, vocal range classifications within vocal music and its use in opera are arguably exclusive in nature.