Nargis Periodic Review.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar Education Sector Snapshot for Comprehensive School Safety and Education in Emergencies

Myanmar Education Sector Snapshot for Comprehensive School Safety and Education in Emergencies Photo Courtesy of: Save the Children Myanmar Myanmar Education Sector Snapshot for Comprehensive School Safety and Education in Emergencies Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................. i Using and Updating this Education Sector Snapshot ................................................................................ iii Map of Myanmar ................................................................................................................................................ iv List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................. v 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Demographic Context ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Politico-Socio-Economic Context .............................................................................. 1 2. Education Sector Policy and Management Context ..................................... 3 2.1 Education Sector Policy ............................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 National Education System .................................................................................................................... -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Myanmar Transport Infrastructure Brief | 18 January – 24 January 2018 2

Issue 57 | 24 January 2017 News Analysis Myanmar Transport Tenders Companies Infrastructure Brief Data Market Updates MIC approves new logistics centre in upper Myanmar EFR Group aims to bring new facility online by mid-2018 Yangon chief minister visits site of potential deep-sea port U Phyo Min Thein continues to push for the development of a deep-sea port and SEZ in Yangon Region’s southern districts Company of the Week Myanmar-Japan JV launches new container freight station FMIDecaux is set to KMA-Suzue Logistics Myanmar unveils its new CFS in Dagon Seikkan township upgrade 250 Yangon bus-stops to MoC proposes interim budget for infrastructure, housing international standard Regional government shelves underpass projects following a tender win. Extensive river navigation project set to begin next month Construction schedule announced for Magway Region bridge YCDC finalises contract for bus-stop upgrade Second deputy minister appointed for transport and communications Elevated expressway may be implemented without proposal to MIC DCA, Chin State officials discuss airport projects President nominates new construction minister European company awarded seismic acquisition contract YPS implementation will commence shortly Yangon traffic control centre irks government again Large portion of Tanintharyi Region budget used on roads Project of the Week Construction begins on bridge spanning Kaladan River Malaysian infrastructure developer scopes opportunities in Myanmar Groundwork on the Road upgrade in Ayeyarwady set to improve connectivity in the delta Falam Airport project YBS operator chosen to implement new airport shuttle in Chin State is over New traffic alert system in the works 25% complete as of Myanmar Transport Infrastructure Monitor to launch new format mid-January. -

Despite Having Their Different Opinions, Service Personnel Need to Serve Dutifully No Matter What Government Takes Office: Senior General

CATTLE FARMING NEEDS TO ADAPT TO MODERN WAYS PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Virtual meeting held for rice procurement, Union Education Minister visits export issues refresher courses in Nay Pyi Taw PAGE-4 PAGE-5 Vol. VII, No. 341, 11th Waxing of Tabaung 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Tuesday, 23 March 2021 Despite having their different opinions, service personnel need to serve dutifully no matter what government takes office: Senior General Chairman of the State Administration Council Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Senior General Min Aung Hlaing delivers address at council meeting (7/2021) in Nay Pyi Taw on 22 March 2021. THE State Administration Dwe, Joint Secretary Lt-Gen Ye a certain degree. Regardless been enacted, measures to ex- The majority of civil serv- Council held its meeting Win Oo and Union Minister for of their residential place, party ercise and control them should ants have been serving for (7/2021) at the meeting room of Home Affairs Lt-Gen Soe Htut. and ethnic origin, the council be taken into consideration. many years. They are therefore the Council Chairman’s Office in In his address, the Senior members must collectively join Since it assumed the coun- urged to return to work. Despite Nay Pyi Taw yesterday, with an General said missions of the hands with the desire to serve cil duties, arrangements have having their different opinions, address delivered by Chairman Council were presented and the national interest. Regarding been made to reopen schools. service personnel need to serve of State Administration Coun- discussed. The council mem- the review of the laws discussed Some of the teachers of the dutifully no matter what govern- cil Commander-in-Chief of De- bers put forward region-we by them at the previous meet- basic education schools are ment takes office. -

46390-003: Power Distribution Improvement Project

Environmental and Social Monitoring Report #5th Semi-Annual Report 31 December 2018 Project No. 46390-003, Loan 3084 MYA: Power Distribution Improvement Project Prepared by Yangon Electricity Supply Enterprise (YESC) through the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) of the Union of the Myanmar Republic and the Asian Development Bank. This Environmental and Social Monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or área. 1 | P a g e The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Electricity and Energy Yangon Electricity Supply Corporation Power Distribution Improvement Project Loan No: 3084-MYA (SF) Semi-annually Social Monitoring Report July-December 2018 Region : Yangon (Area 1) 2 | P a g e Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................. 3 Scope ..................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction and Project Characteristics ..................................................................... 4 1.1 Background .................................................................................................. -

Republic of the Union of Myanmar President Office Notification No. 92/2012

Published on Myanmar President Office (http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en) Home > Republic of the Union of Myanmar President Office Notification No. 92/2012 Republic of the Union of Myanmar President Office Notification No. 92/2012 Sun, 12/02/2012 - 11:29 Republic of the Union of Myanmar President Office Notification No. 92/2012 3rd Waxing of Tazaungmon 1374 ME 1 December 2012 Formation of Investigation Commission 1. “Investigation Commission” is formed with the following persons to go through whether copper mining should be continued and to find out the true situation about the recent containing of protest in Letpadaungtaung Copper Mining Project in Salingyi Township, Monywa District, Sagaing Region. (a) Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Chairperson Pyithu Hluttaw representative Yangon Region, Kawhmu Township Constituency (b) U Lun Thi Member Pyithu Hluttaw representative Yangon Region, Kungyangon Township Constituency (c) U Than Myint Member Pyithu Hluttaw representative Sagaing Region, Salingyi Township Constituency (d) Daw Khin San Hlaing Member Pyithu Hluttaw representative Sagaing Region, Pale Township Constituency (e) U Zaw Myint Pe Member Amyotha Hluttaw representative Mandalay Region, Constituency No. 5 (f) U Khin Maung Yi Member Amyotha Hluttaw representative Ayeyawady Region, Constituency No.6 (g) U Aung Kyi Nyunt Member Amyotha Hluttaw representative Magway Region Constituency No.4 (h) U Khin Maung Swe Member Chairman, National Democratic Forces Party (i) U Myo Nyunt Member General Secretary Democracy and Peace Party (j) Dr Win Maung -

Hlegu) Industrial Park Project - Located at Hlaeku Township - Jointly Developed by the Myanmar – Singapore , Has a Total Area of 1150 Acres ( 465 Hta

Outlines Why Invest in Yangon? Investment Environment in Yangon Mega Projects in Yangon Yangon Region Investment Committee 2 YANGON Heritage. Green. Livable. Commercial Region of Myanmar 3 „We are very ambitious to develop the Yangon region rapidly and create a city where sustainable economic development. We will try to create a Yangon that will be a vitally important city, not only for Myanmar but also for ASEAN countries. We are creating enabling investment environment to promote investment in Yangon Region‟ Chief Minister Yangon Region Government 4 Why Invest in Yangon ? Strong Economic Factors GDP 24 % GDP Growth Rate 9.8 % Manufacturing Sector 41% Trade Sector 28% Services Sector 29% Construction Sector 25% Electric Power Sector 22% Yangon City Working Population 70% Smallest Region 10,171 sq km Population 7.4 mil ( Yangon Region) Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon 6 YANGON ACCOUNTS FOR - CLOSE TO 85 % OF THE COUNTRY’S TRADE - OVER HALF OF THE TOTAL INVESTMENTS INTO THE COUNTRY 7 “Yangon Region” : Investment Hub in Myanmar 8 Mission To Attain Green Growth Economy of Yangon Region by Promoting Responsible and Quality Investment 9 Investment Priority Sectors Manufacturing Sector • Export Promotion Industries • Import Substitution Industries Infrastructure Sector • Power Generation, Transmission and Distribution • Construction of affordable Housing • Industrial Estate • Construction of Seaport, River Port and Dry Port • Construction of Road, Bridge and Railway Line • City Development Activities Information -

Khin Htar Nwe EMPA.Pdf (591

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PROGRAMME A STUDY ON LAND ADMINISTRATION OF THE GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT IN THANLYIN AND KYAUKTAN TOWNSHIPS, YANGON REGION KHIN HTAR NWE EMPA –18 (14th Batch) AUGUST, 2018 1 YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PROGRAMME A STUDY ON LAND ADMINISTRATION OF THE GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT IN THANLYIN AND KYAUKTAN TOWNSHIPS, YANGON REGION A thesis submitted as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Administration (MPA) Supervised by Submitted by Daw Sintheingie Khin Htar Nwe Professor/head (Retd.) Roll No. 18 Department of Economics EMPA 14th Batch Yangon University of Economics 2015-2018 AUGUST, 2018 2 YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PROGRAMME This is certify that this thesis entitled: A Study On Land Administration Of The General Administration Department In Thanlyin And Kyauktan Townships, Yangon Region submitted as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Administration has been accepted by the Board of Examiners. Board of Examiners 1. Professor Dr. Tun Aung Pro-Rector Yangon University of Economics (Chief Examiner) 2. Professor Dr. Daw Ni Lar Myint Htoo Pro-Rector Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 3. Professor Dr. Kyaw Min Htun Pro-Rector (Retd.) Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 4. Professor Dr. Phyu Phyu Ei Programme Director and Head of Department Department of Applied Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 5. U Thein Naing Associate Professor Department of Applied Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) August, 2018 3 ABSTRACT This study focuses on Land Administration of the General Administration Department in Thanlyin and Kyauktan Townships, which is located in Thilawa SEZ for the period 2007 - 2017. -

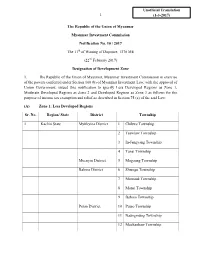

Zone Notification

Unofficial Translation 1 (1-3-2017) The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Myanmar Investment Commission Notification No. 10 / 2017 The 11th of Waning of Dapotwe, 1378 ME (22nd February 2017) Designation of Development Zone 1. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Myanmar Investment Commission in exercise of the powers conferred under Section 100 (b) of Myanmar Investment Law, with the approval of Union Government, issued this notification to specify Less Developed Regions as Zone 1, Moderate Developed Regions as Zone 2 and Developed Regions as Zone 3 as follows for the purpose of income tax exemption and relief as described in Section 75 (a) of the said Law: (A) Zone 1: Less Developed Regions Sr. No. Region/ State District Township 1 Kachin State Myitkyina District 1 Chibwe Township 2 Tsawlaw Township 3 In-Jangyang Township 4 Tanai Township Moenyin District 5 Mogaung Township Bahmo District 6 Shwegu Township 7 Momauk Township 8 Mansi Township 9 Bahmo Township Putao District 10 Putao Township 11 Naungmung Township 12 Machanbaw Township 2 13 Sumprabum Township 14 Kaunglanhpu Township 2 Kayah State Bawlakhe District 1 BawlakheTownship 2 Hpasaung Township 3 Mese Township Loikaw District 4 Loikaw Township 5 Demawso Township 6 Hpruso Township 7 Shataw Township 3 Kayin State Hpa-an District 1 Hpa-an Township 2 Hlaignbwe Township 3 Papun Township 4 Thandaunggyi Township Kawkareik District 5 Kawkareik Township 6 Kyain Seikkyi Township Myawady District 7 Myawady Township 4 Chin State Falam District 1 Falam Township 2 Tiddim Township 3 Hton Zan Township -

List of Townships of Burma

State/ Region Name of District Township Central Burma Magway Region Gangaw District Gangaw Township Central Burma Magway Region Gangaw District Tilin Township Central Burma Magway Region Gangaw District Saw Township Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Magway Township Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Yenangyaung Township Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Chauck Township Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Taungdwingyi Township Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Myothit Township Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Natmauk Township Central Burma Magway Region Minbu District Minbu Township Central Burma Magway Region Minbu District Pwintbyu Township Central Burma Magway Region Minbu District Ngape Township Central Burma Magway Region Minbu District Salin Township Central Burma Magway Region Minbu District Sidoktaya Township Central Burma Magway Region Pakokku District Myaing Township Central Burma Magway Region Pakokku District Pakokku Township Central Burma Magway Region Pakokku District Pauk Township Central Burma Magway Region Pakokku District Seikphyu Township Central Burma Magway Region Pakokku District Yesagyo Township Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Aunglan Township Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Kamma Township Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Mindon Township Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Minhla Township Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Sinbaungwe Township Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Thayet Township Central -

OCHA Situation Report No

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS Myanmar Cyclone Nargis Yangon Hub Update No. 7 12 February 2009 (Reporting period 28 January- 11 February 2009) OVERVIEW AND KEY DEVELOPMENTS • Taiwan Tzu-chi Buddhist Group will build 390 houses at San Pya Ward, Kungyangon Township. Asia World and Kyaw Thar Construction Company have been contracted to undertake the project. • Some informally settled families (about 80) at Let Khote Kone on the outskirts of Kungyangon are requesting support in the form of latrines and other basic assistance. Durable solutions for the long-term future of these families are currently being discussed by humanitarian partners. • The authorities in Mee Pya Village of Kyaut Tan Township are advising 172 households, currently residing on the seaside of planned embankments, to move to a designated area inside the embankments. • On 7 February 2009 at Kungyangon, the Ministry of Health, Department of Traditional Medicine and the Nippon Foundation, Japan, distributed 500 Traditional Medicine Boxes to 500 villages in 13 townships of Yangon Division. The Deputy Minister of Energy, Brigade General Than Htay and the Chairman of Nippon Foundation, Mr. Yohei Sasakawa, attended the ceremony. • On 10 February 2009, a ceremony was held to open 29 low cost latrines donated by Myittar Foundation for cyclone affected people of Myo Thit Road 6, Kungyangon. The Managing Director of the Ministry of Energy and the Chairman of the Township Peace and Development Council (TPDC) attended. • The second National Immunization Day was held on 10 February 2009 in all townships and oral vaccine on polio was also given to children. -

Syriam District Volume A

BURMA GAZETTEER. SYRIAM DISTRICT VOLUME A COMPILED BY J. S. FURNIVALL, I.C.S. (ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER) ASSISTANT SETTLEMENT OFFICER AND COMPLETED BY W. S. MORRISON, I.C.S. (ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER) SETTLEMENT OFFICER RANGOON OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA 1914 [price,--Rs. 2-4-0=3s. 5d.] LIST OF AGENT SALE OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA: THACKER, SPINK & Co., Calcutta and Simla. W. NEWMAN & Co., Calcutta. THACKER & Co., Ltd., Bombay. HIGGINBOTHAM & Co., Madras. SUPERINTENDENT, AMERICAN BAPTIST MISSION PRESS, Rangoon. * D. B. TARPOREVALA & SONS & Co, 103, Medows Street, Fort, Bombay. BUTTERWORTH & Co. (India), Ltd., 8-2, Hastings Street, Calcutta. IN ENGLAND: HENRY S. KING & Co., 65, Cornhill, E.C. A, CONSTABLE & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, W.C. KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRÜBNER & Co., 68--74, Carter Lane, E.C. BERNARD QUARITCH, II, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, W. P. S. KING & SON, 2 & 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, S.W. GRINDLAY & Co., 54, Parliament Street, S.W. T. FISHER UNWIN, I, Adelphi Terrace, W.C. W. THACKER & Co., 2, Creed Lane, Ludgate Hill, E.C. LUZAC & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, W.C. OLIVER & BOYD, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. E. PONSONBY, LTD., 116, Grafton Street, Dublin. B. H. BLACKWELL, 50 & 51, Broad Street, Oxford. DEIGHTON BELL & Co., Trinity Street, Cambridge. ON THE CONTINENT: R. FRIEDLANDER & SOHN, II, Carlstrasse, Berlin, Germany. OTTO HARRASSOWITZ, Leipzig, Germany. KARL W. HIERSEMANN, Leipzig, Germany. ERNEST LEROUX, 28, Rue Bonaparte, Paris, France MARTINUS NIJHOFF, The Hague, Holland. * For· the ease of official publications excluding those of the Legisiative Department of the Government of Burma. TABLE OF CONTENTS.