10.2478/Genst-2020-0015 BOOK REVIEW: Jane Austen: Glose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lukacs the Historical Novel

, LUKACS THE HISTORICAL NOVEL THE HISTORICAL NOVE�_ Georg Lukacs TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY Hannah and Stanley Mitchell Preface to the American edition by Irving Howe BEACON PRESS BOSTON First published in Russia, translated from the German, Moscow, I9 37 First German edition published in I955 in East Germany Second German edition published in I961 in West Germany English translation, from the second German edition, first published in 1962 by Merlin Press Limited, London Copyright© I962 by Merlin Press Limited First published as a Beacon Paperback in I963 by arrangement with Merlin Press Limited Library of Congress catalog card number: 63-8949 Printed in the United States of America ERRATA page II, head. For Translator's Note read Translators' Note page 68, lines 7-8 from bottom. For (Uproar in the Cevennes) read (The Revolt in the Cevennes) page 85, line I2. For with read which page ll8, para. 4, line 6. For Ocasionally read Occasionally page 150, line 7 from bottom. For co-called read so-called page I 54, line 4. For with which is most familiar read with which he is most familiar page I79, line 4 from bottom. For the injection a meaning read the injection of a meaning page I80, para. 4, line l. For historical solopism read historical solecism page I97, para. 3, line 2. For Gegenwartighkeit read Gegenwartigkeit page 22I, line 4 from bottom. For Bismark read Bismarck page 237, para. 3, line 2. For first half of the eighteenth century read first half of the nineteenth century page 246, para. 2, line 9. -

The Story of Chivalry

MISCELLANEOUS. THE STORY OF CHIVALRY. In a series of books entitled "Social England," published by Swan Sonnen- schein & Co., of London, and by The Macmillan Company, of New York, the at- tempt has been made to reconsider certain phases of English life that do not re- ceive adequate treatment in the regular histories. To understand what a nation was, to understand its greatness and weakness, we must understand the way in which its people spent their lives, what they cared for, what they fought for, what they lived for. Without this, which constitutes nine tenths of a nation's life, his- tory becomes a ponderous chronicle, full of details and without a guiding principle. Therefore, not only politics and wars, but also religion, commerce, art, literature, law, science, and agriculture, must be intelligently studied if our historical picture of a nation is to be complete. Vast indeed is the field which is here to be covered, the following being some of the subjects requiring distinct treatment : the influence upon the thought of geo- graphical discovery, of commerce, and of science; the part inventions have played, the main changes in political theories, the main changes in English thought upon great topics, such as the social position of women, of children, and of the church, the treatment of the indigent poor and the criminal, the life of the soldier, the sailor, the lawyer and the physician, the life of the manor, the life of the working classes, the life of the merchants, the universities, the fine arts, music, the horues of the people, and the implements of the people, the conception of the duties of the nobleman and of the statesman, the story of crime, of the laws of trade, com- merce, and industry. -

Legendary Author Sir Walter Scott Is Star of Saturday Night Show

19/03/21 Legendary author Sir Walter Scott is star of Saturday night show An international celebration for the 250th anniversary of the life and works of Sir Walter Scott gets underway this weekend (Saturday March 20th) with an online broadcast of a spectacular light show from the Scottish Borders. Scott fans around the globe are being invited to view the stunning display at Smailholm Tower by visiting the website, www.WalterScott250.com, at 6pm (GMT) on Saturday, which is World Storytelling Day (March 20th). The broadcast will feature well-known Scott enthusiasts, including Outlander author Diana Gabaldon who will share how Scott inspired her and what her writing has in common with the 19th Century author. This will be followed by the world premiere of a brand-new short film of the Young Scott, created by artist and director, Andy McGregor, which will be projected onto the 15th-century tower. The 250th anniversary launch event is being funded by EventScotland and organised by Abbotsford, home of Sir Walter Scott, on behalf of the international Walter Scott 250 Partnership. Smailholm Tower, which is owned by Historic Environment Scotland, was chosen as the location to start the celebrations because of its influence on Scott as a child. The tower is next door to the farm where Scott lived as a boy, and his early experiences here continued to inspire him throughout his life. The programme for the launch evening is: 6pm Start of broadcast at www.WalterScott250.com. This will be presented by Brian Taylor, former BBC correspondent and past President of the Edinburgh Sir Walter Scott Club. -

Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion

religions Article Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion Stephen S. Bush Department of Religious Studies, Brown University, 59 George Street, Providence, RI 02912, USA; [email protected] Received: 20 July 2017; Accepted: 20 August 2017; Published: 25 August 2017 Abstract: William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson are both committed individualists. However, in what do their individualisms consist and to what degree do they resemble each other? This essay demonstrates that James’s individualism is strikingly similar to Emerson’s. By taking James’s own understanding of Emerson’s philosophy as a touchstone, I argue that both see individualism to consist principally in self-reliance, receptivity, and vocation. Putting these two figures’ understandings of individualism in comparison illuminates under-appreciated aspects of each figure, for example, the political implications of their individualism, the way that their religious individuality is politically engaged, and the importance of exemplarity to the politics and ethics of both of them. Keywords: Ralph Waldo Emerson; William James; transcendentalism; individualism; religious experience 1. Emersonian Individuality, According to James William James had Ralph Waldo Emerson in his bones.1 He consumed the words of the Concord sage, practically from birth. Emerson was a family friend who visited the infant James to bless him. James’s father read Emerson’s essays out loud to him and the rest of the family, and James himself worked carefully through Emerson’s corpus in the 1870’s and then again around 1903, when he gave a speech on Emerson (Carpenter 1939, p. 41; James 1982, p. 241). -

Byron and the Scottish Literary Tradition Roderick S

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 16 1979 Byron and the Scottish Literary Tradition Roderick S. Speer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Speer, Roderick S. (1979) "Byron and the Scottish Literary Tradition," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 14: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol14/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roderick S. Speer Byron and the Scottish Literary 1radition It has been over forty years since T. S. Eliot proposed that we consider Byron as a Scottish poet. 1 Since then, anthologies of Scottish verse and histories of Scottish literature seldom neglect to mention, though always cursorily, Byron's rightful place in them. The anthologies typically make brief reference to Byron and explain that his work is so readily available else where it need be included in short samples or not at al1.2 An historian of the Scots tradition argues for Byron's Scottish ness but of course cannot treat a writer who did not use Scots. 3 This position at least disagrees with Edwin Muir's earlier ar gument that with the late eighteenth century passing of Scots from everyday to merely literary use, a Scottish literature of greatness had passed away.4 Kurt -

JACQUES ROUSSEAU's EMILE By

TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE NOVELISTIC DIMENSION OF JEAN- JACQUES ROUSSEAU’S EMILE by Stephanie Miranda Murphy A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Stephanie Miranda Murphy 2020 Toward an Understanding of the Novelistic Dimension of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile Stephanie Miranda Murphy Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science ABSTRACT The multi-genre combination of philosophic and literary expression in Rousseau’s Emile provides an opportunity to explore the relationship between the novelistic structure of this work and the substance of its philosophical teachings. This dissertation explores this matter through a textual analysis of the role of the novelistic dimension of the Emile. Despite the vast literature on Rousseau’s manner of writing, critical aspects of the novelistic form of the Emile remain either misunderstood or overlooked. This study challenges the prevailing image in the existing scholarship by arguing that Rousseau’s Emile is a prime example of how form and content can fortify each other. The novelistic structure of the Emile is inseparable from Rousseau’s conception and communication of his philosophy. That is, the novelistic form of the Emile is not simply harmonious with the substance of its philosophical content, but its form and content also merge to reinforce Rousseau’s capacity to express his teachings. This dissertation thus proposes to demonstrate how and why the novelistic -

The Abolition of Emerson: the Secularization of America’S Poet-Priest and the New Social Tyranny It Signals

THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Washington, DC February 1, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Justin James Pinkerman All Rights Reserved ii THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Dr. Richard Boyd, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Motivated by the present climate of polarization in US public life, this project examines factional discord as a threat to the health of a democratic-republic. Specifically, it addresses the problem of social tyranny, whereby prevailing cultural-political groups seek to establish their opinions/sentiments as sacrosanct and to immunize them from criticism by inflicting non-legal penalties on dissenters. Having theorized the complexion of factionalism in American democracy, I then recommend the political thought of Ralph Waldo Emerson as containing intellectual and moral insights beneficial to the counteraction of social tyranny. In doing so, I directly challenge two leading interpretations of Emerson, by Richard Rorty and George Kateb, both of which filter his thought through Friedrich Nietzsche and Walt Whitman and assimilate him to a secular-progressive outlook. I argue that Rorty and Kateb’s political theories undercut Emerson’s theory of self-reliance by rejecting his ethic of humility and betraying his classically liberal disposition, thereby squandering a valuable resource to equip individuals both to refrain from and resist social tyranny. -

Romanticism Romanticism Dominated Literature, Music, and the Arts in the First Half of the 19Th Century

AP ACHIEVER Romanticism Romanticism dominated literature, music, and the arts in the first half of the 19th century. Romantics reacted to the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and science, instead stressing the following: • Emotions – Taking their cue from Rousseau, Romantics emphasized feeling and passion as the wellspring of knowledge and creativity. • Intuition – Science alone cannot decipher the world; imagination and the “mind’s eye” can also reveal its truths. • Nature – Whereas the philosophes studied nature analytically, the Romantics drew inspiration and awe from its mysteries and power. • Nationalism – Romanticism found a natural connection with nationalism; both emphasized change, passion, and connection to the past. • Religion (Supernatural) – Romanticism coincided with a religious revival, particularly in Catholicism. Spirit, mysticism, and emotions were central to both. • The unique individual – Romantics celebrated the individual of genius and talent, like a Beethoven or a Napoleon, rather than what was universal in all humans. With these themes in mind, consider the topics and individuals below: • THEME MUSIC AND EXAMPLE BASE Prior to the 19th century, you will have noted the rise of objective thinking toward the natural world (Scientific Revolution, Enlightenment), but with the Romantics, we see one of the first strong reactions to the notion that all knowledge stems from the scientific method (OS). Though not the first to do so, the Romantics embrace the subjectivity of experience in a singular and seductive manner. Literature and History Lord Byron (1788-1824 ) – As famous for his scandalous lifestyle as for his narrative poems, Lord Byron died from fever on his way to fight for Greek independence, a cause he supported in his writings. -

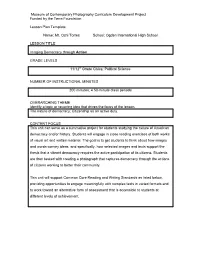

Lesson Plan Template

Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation Lesson Plan Template Name: Mr. Ozni Torres School: Ogden International High School LESSON TITLE Imaging Democracy through Action GRADE LEVELS 11/12th Grade Civics; Political Science NUMBER OF INSTRUCTIONAL MINUTES 200 minutes; 4 50-minute class periods OVERARCHING THEME Identify a topic or recurring idea that drives the focus of the lesson. The nature of democracy; Citizenship as an active duty. CONTENT FOCUS This unit can serve as a summative project for students studying the nature of American democracy and/or history. Students will engage in close reading exercises of both works of visual art and written material. The goal is to get students to think about how images and words convey ideas, and specifically, how selected images and texts support the thesis that a vibrant democracy requires the active participation of its citizens. Students are then tasked with creating a photograph that captures democracy through the actions of citizens working to better their community. This unit will support Common Core Reading and Writing Standards as listed below, providing opportunities to engage meaningfully with complex texts in varied formats and to work toward an alternative form of assessment that is accessible to students at different levels of achievement. Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation ART ANALYSIS List the names of artist(s) and titles of their artwork that students will do close reading exercises on. Artist Work of Art John Trumbull 12’ X 18’ 1818 Rotunda; U.S. Capitol D eclaration of Independence Paul Shambroom 2’9” X 5’6” 1999 Museum of Contemporary Photography Markl e, IN (pop. -

ED331751.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 331 751 SO 020 969 AUTHOR Brooks, B. David TITLE Success through Accepting Responsibility. Principal's Handbook: Creating a School Climate of Responsibility. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Thomas Jefferson Research Center, Pasadena, Calif. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 130p. AVAILABLE FROM Thomas Jefferson Research Center, 202 South Lake Avenue, Suite 240, Pasadena, CA 91101. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Guides; *Administrator Role; Citizenship Education; *Educational Environment; Educational Planning; Elementary Secondary Education; Ethics; *pri4cipals; School Activities; Self Esteem; Skill Development; Social Responsibility; Social Studies; *Student Educational Objectives; *Student Responsibility; *Success; Values; Vocabulary Development ABSTRACT Success Through Accepting Responsibility (STAR)is primarily a language program, although the valueshave a relationship to social studies topics. Through language developmentthe words, concepts, and skills of personal responsibilitymay be taught. This principal's handbook outlines a school-wide systematicapproach for building a positive school climate around self-esteemand personal responsibility. Following an introduction, the handbookis organized into eight sections: planning and implementation;kick-off activities; year-long activities; sustainingevents and activities; end-of-year activities; parent and communityinvolvement; evaluations and reports; and principal's memos. (DB) ** ***** **************************************************************** -

God Within": the Experience and Manifestation of Emerson's Evolving Philosophy of Intuition

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-05-21 Discovering the "God Within": The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson's Evolving Philosophy of Intuition Anne Tiffany Turner Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Turner, Anne Tiffany, "Discovering the "God Within": The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson's Evolving Philosophy of Intuition" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4099. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4099 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Discovering the “God Within”: The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson’s Evolving Philosophy of Intuition Anne Turner A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Edward Cutler, Chair Jesse Crisler Emron Esplin Department of English Brigham Young University April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Anne Turner All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Discovering the “God Within”: The Experience and Manifestation of Emerson’s Evolving Philosophy of Intuition Anne Turner Department of English, BYU Master of Art Investigating individual subjectivity, Ralph Waldo Emerson traveled to Europe following the death of his first wife, Ellen Tucker Emerson, and his resignation from the Unitarian ministry. His experience before and during the voyage contributed to the evolution of a self-intuitive philosophy, termed selbstgefühl by the German Romantics and altered his careful style of composition and delivery to promote the integrity of individual subjectivity as the highest authority in the deduction of truth. -

Graduate Seminar in American Political Thought University of Washington Autumn 2020 5 Credits Wednesday, 1:30-4:20 P.M

DEMOCRACY AS A WAY OF LIFE Political Science 516: Graduate Seminar in American Political Thought University of Washington Autumn 2020 5 Credits Wednesday, 1:30-4:20 p.m. Remote Learning Version Course Website: https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1401667 Jack Turner 133 Gowen [email protected] Office Hours: By appointment DESCRIPTION Democracy is often conceived of as a mode of government or form of rule, but both advocates and critics of democracy have just as frequently emphasized its significance as a social and cultural way of life, a manner of being in the world. Plato called democracy “the most attractive of the regimes . like a coat of many colors”; he also worried how democracy toppled the most basic relations of authority. Children defy their parents in a democracy, and students their teachers. Horses and donkeys wander “the streets with total freedom, noses in the air, barging into any passer-by who fails to get out of the way.” This seminar analyzes democracy as a distinctive way of life as it arose after the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions. It begins with the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century transatlantic debates about the meaning of democratic revolution (Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine), segues to the flowering of democratic culture in the United States and its relationship to white supremacy (David Walker, Alexis de Tocqueville, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau), examines the nature of democratic education, popular sovereignty, and racial violence in mass, industrializing society (John Dewey and Ida B. Wells), and probes the connections between democracy, race, and empire in the twentieth century (W.E.B.