Invasion, Surveillance, Biopolitics, and Governmentality: Representations from Tactical Media to Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

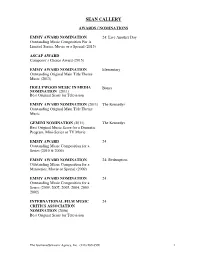

Sean Callery

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD Composer’s Choice Award (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY TELEVISION SERIES JESSICA JONES (series) Melissa Rosenberg, Jeph Loeb, exec. prods. ABC / Marvel Entertainment / Tall Girls Melissa Rosenberg, showrunner BONES (series) Barry Josephson, Hart Hanson, Stephen Nathan, Fox / 20 th Century Fox Steve Bees, exec. prods. HOMELAND (pilot & series) Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Avi Nir, Gideon Showtime / Fox 21 Raff, Ran Telem, exec. prods. ELEMENTARY (pilot & series) Carl Beverly, Robert Doherty, Sarah Timberman, CBS / Timberman / Beverly Studios Craig Sweeny, exec. prods. MINORITY REPORT (pilot & series) Kevin Falls, Max Borenstein, Darryl Frank, 20 th Century Fox Television / Fox Justin Falvey, exec. prods. Kevin Falls, showrunner MEDIUM (series) Glenn Gordon Caron, Rene Echevarria, Kelsey Paramount TV /CBS Grammer, Ronald Schwary, exec. prods. 24: LIVE ANOTHER DAY (event-series) Kiefer Sutherland, Howard Gordon, Brian 20 TH Century Fox Grazer, Jon Cassar, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, David Fury, exec. -

The Art of 'Governing Nature': 'Green' Governmentality

THE ART OF ‘GOVERNING NATURE’: ‘GREEN’ GOVERNMENTALITY AND THE MANAGEMENT OF NATURE by KRISTAN JAMES HART A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Environmental Studies In conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Environmental Studies Queen„s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2011) Copyright ©Kristan James Hart, 2011 Abstract This thesis seeks to unpack the notions of Michael Foucault's late work on governmentality and what insights it might have for understanding the „governing of nature‟. In doing this it also operates as a critique of what is often termed 'resourcism', a way of evaluating nature which only accounts for its utility for human use and does not give any acceptance to the idea of protecting nature for its own sake, or any conception of a nature that cannot be managed. By utilizing a study of the govern-mentalities emerging throughout liberalism, welfare-liberalism and neoliberalism I argue that this form of 'knowing' nature-as-resource has always been internal to rationalities of liberal government, but that the bracketing out of other moral valuations to the logic of the market is a specific function of neoliberal rationalities of governing. I then seek to offer an analysis of the implications for this form of nature rationality, in that it is becoming increasingly globalized, and with that bringing more aspects of nature into metrics for government, bringing new justifications for intervening in „deficient‟ populations under the rubric of „sustainable development. I argue, that with this a new (global) environmental subject is being constructed; one that can rationally assess nature-as-resource in a cost-benefit logic of wise-use conservation. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

Foxtel in 2016

Media Release: Thursday November 5, 2015 Foxtel in 2016 In 2016, Foxtel viewers will see the return of a huge range of their favourite Australian series, with the stellar line-up bolstered by a raft of new commissions and programming across drama, lifestyle, factual and entertainment. Foxtel Executive Director of Television Brian Walsh said: “We are proud to announce the re- commission of such an impressive line-up of our returning Australian series, which is a testament to our production partners, creative teams and on air talent. In 2016, our subscribers will see all of their favourite Australian shows return to Foxtel, as well as new series we are sure will become hits with our viewers. “Our growing commitment to producing exclusive home-made signature programming for our subscribers will continue in 2016, with more Australian original series than ever before. Our significant investment in acquisitions will also continue, giving Foxtel viewers the biggest array of overseas series available in Australia. “In 2016 we will make it even easier for our subscribers to enjoy Foxtel. Our on demand Foxtel Anytime offering will continue to be the driving force behind the most comprehensive nationwide streaming service available to all customers as part of their package. Over the next year, Foxtel will provide its subscribers with more than 16,000 hours of programming, available anytime.” “To complement our outstanding on demand offering, our Box Sets channel is designed for our binge- watching viewers who want to watch or record full series of their favourite shows from Australia and around the world. It’s the only channel of its kind in our market and content on Box Sets will also increase next year, giving our subscribers even more freedom to watch what they want, when they want.” “Foxtel also continues to be the best movies destination in Australia. -

![TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres En Séries (I) » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 18 Mai 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1578/tv-series-9-2016-%C2%AB-guerres-en-s%C3%A9ries-i-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-mars-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-18-mai-2021-381578.webp)

TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres En Séries (I) » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 18 Mai 2021

TV/Series 9 | 2016 Guerres en séries (I) Séries et guerre contre la terreur TV series and war on terror Marjolaine Boutet (dir.) Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/617 DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.617 ISSN : 2266-0909 Éditeur GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Référence électronique Marjolaine Boutet (dir.), TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres en séries (I) » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 mars 2016, consulté le 18 mai 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/617 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/tvseries.617 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 18 mai 2021. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 Ce numéro explore de façon transdisciplinaire comment les séries américaines ont représenté les multiples aspects de la lutte contre le terrorisme et ses conséquences militaires, politiques, morales et sociales depuis le 11 septembre 2001. TV/Series, 9 | 2016 2 SOMMAIRE Préface. Les séries télévisées américaines et la guerre contre la terreur Marjolaine Boutet Détours visuels et narratifs Conflits, filtres et stratégies d’évitement : la représentation du 11 septembre et de ses conséquences dans deux séries d’Aaron Sorkin, The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) et The Newsroom (HBO, 2012-2014) Vanessa Loubet-Poëtte « Tu n’as rien vu [en Irak] » : Logistique de l’aperception dans Generation Kill Sébastien Lefait Between Unsanitized Depiction and ‘Sensory Overload’: The Deliberate Ambiguities of Generation Kill (HBO, 2008) Monica Michlin Les maux de la guerre à travers les mots du pilote Alex dans la série In Treatment (HBO, 2008-2010) Sarah Hatchuel 24 heures chrono et Homeland : séries emblématiques et ambigües 24 heures chrono : enfermement spatio-temporel, nœud d’intrigues, piège idéologique ? Monica Michlin Contre le split-screen. -

GEO 755 Political Ecology: Nature, Culture, Power Syllabus

Political Ecology: Nature, Culture, Power Geography 755 Tuesdays, 5:00-7:45pm, Eggers 155 Professor Tom Perreault Eggers 529 Office Hours: Tuesdays 2:00-4:00pm or by appointment [email protected] 443-9467 Course Overview This course surveys key themes in the field of political ecology. We will examine the political economies of environmental change, as well as the ways in which our understandings of nature are materially and discursively bound up with notions of culture and the production of subjectivity. The course does not attempt to present a comprehensive review of the political ecology literature. Rather, it is a critical exploration of theories and themes related to nature, political economy, and culture; themes that, to my mind, fundamentally underlie the relationship between society and environment. The course is divided into four sections: (I) “Foundations of Political Ecology: Core Concepts and Key Debates” examines the intellectual foundations and key debates of political ecology as a field; (II) “Governing Nature” examines capitalist transformations of nature, with a particular focus on neoliberalism and commodification, and the modes of environmental governance they engender; (III) “Nature and Subjectivity” focuses on subjectivity and the production of social difference, and how these are experienced in relation to nature; and (IV) “Spaces and Scales of Political Ecology” considers three key spheres of political ecological research: (a) agrarian political economy and rural livelihoods; (b) urban political ecology; and (c) the Anthropocene. No seminar can be completely comprehensive in its treatment of a given field, and this class is no exception. There are large and well-developed literatures within political ecology that are not included in the course schedule. -

6. Neoliberal Governmentality: Foucault on the Birth of Biopolitics

MICHAEL A. PETERS 6. NEOLIBERAL GOVERNMENTALITY: FOUCAULT ON THE BIRTH OF BIOPOLITICS The political, ethical, social, philosophical problem of our days is not to liberate the individual from the State and its institutions, but to liberate ourselves from the State and the type of individualisation linked to it (Foucault, 1982, p. 216). Power is exercised only over free subjects, and only insofar as they are free. (Foucault, 1982, p. 221). INTRODUCTION In his governmentality studies in the late 1970s Foucault held a course at the Collège de France the major forms of neoliberalism, examining the three theoretical schools of German ordoliberalism, the Austrian school characterised by Hayek, and American neoliberalism in the form of the Chicago school. Among Foucault’s great insights in his work on governmentality was the critical link he observed in liberalism between the governance of the self and government of the state – understood as the exercise of political sovereignty over a territory and its population. He focuses on government as a set of practices legitimated by specific rationalities and saw that these three schools of contemporary economic liberalism focused on the question of too much government – a permanent critique of the state that Foucault considers as a set of techniques for governing the self through the market. Liberal modes of governing, Foucault tells us, are distinguished in general by the ways in which they utilise the capacities of free acting subjects and, consequently, modes of government differ according to the value and definition accorded the concept of freedom. These different mentalities of rule, thus, turn on whether freedom is seen as a natural attribute as with the philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, a product of rational choice making, or, as with Hayek, a civiliz- ational artefact theorised as both negative and anti-naturalist. -

Cape Coral Breeze

THREE DAYS A WEEK POST COMMENTS AT CAPE-CORAL-DAILY-BREEZE.COM Series CAPE CORAL sweep St. Lucie Mets hand Miracle third straight loss BREEZE — SPORTS MID-WEEK EDITION WEATHER: Partly Cloudy• Tonight: Mostly Clear • Friday: Partly Cloudy — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 50, No. 45 Thursday, April 14, 2011 50 cents Stewart requests apology, threatens lawsuit By DREW WINCHESTER on Wednesday. FAC members claimed that Stewart said that he simply information that was presented [email protected] Stewart is eyeing Mayor John Stewart signed a construction wrote the wrong date on the con- contained no malice “toward him Former City Manager Terry Sullivan, Councilmembers Bill contract 11 months prior to City tract, and that he was never in or anybody else.” Stewart plans on moving forward Deile, Pete Brandt, Erick Kuehn Council ever seeing the docu- league with MWH. Grasso said there was “no with his lawsuit against the city and Chris Chulakes-Leetz, and ments. He added that since he was way” he would apologize to and certain members of City Finance Advisory Committee FAC Chairman Don maligned publicly, a public apol- Stewart because he did not make Council, he said Wednesday, member Sal Grasso for the suit, McKiernan also said during the ogy would negate his desire to the presentation Monday night — unless those parties make a public following a presentation on presentation that MWH manipu- move forward with the lawsuit. that was handled by McKiernan apology for statements that he Monday that used Stewart’s name lated population and water usage “Yes, it would take away the — and that he “never accused” said impugned his professional in conjunction with “manipulated projections over the course of need for legal action,” Stewart Stewart of “ever doing anything reputation. -

Review Ordered in Wake of Shooting Provided by the Lake City Police Department in August, Officers Responded to a 911 Dis- Huddleston Looks at Possible Cer on Campus

1 TUESDAY, DECEMBER 18, 2012 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM COUNTY SCHOOLS Officer cleared Safety to get a boost in fatal shooting Armed man was killed in encounter at apartment complex. By TONY BRITT [email protected] A Columbia County grand jury ruled Monday that a Lake City Police officer’s shooting of an armed man during a con- frontation at the Windsong Apartment Complex in August was justified. J e r a m e y S w e e n y , 30, died in the con- f r o n t a t i o n with Lake City Police Officer Brian Bruenger. Sweeny S w e e n y was the vic- tim in a fight with one his roommates before authorities arrived and happened to fit the physical description of the assailant. However, Sweeny was carrying a gun when he Photos by JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter was met by authorities and ABOVE: Students at Westside Elementary load the bus for home Monday. BELOW: April Montalvo kisses her daughter, Eva, 6, after school at Westside on killed in a confrontation when Monday. he pointed the gun a law enforcement officers. According to information Review ordered in wake of shooting provided by the Lake City Police Department in August, officers responded to a 911 dis- Huddleston looks at possible cer on campus. tress call at 2:27 a.m. Tuesday, “We would certainly like to enhance that at the Jitters for some, Aug. 21 at 2720 SW Windsong federal funding as means for elementary level...,” Huddleston said. -

Magisterarbeit 24

„Tell me where the bomb is or I’ll kill your son“– Folter in der TV-Serie „24“ und ihr Einfluss auf die aktuelle Folterdebatte in den Vereinigten Staaten Zur Erlangung des Grades eines Magister Artium der Philosophischen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Westfalen vorgelegt von Jens Wiesner aus Dissen a.T.W. 2008 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ......................................................................................................... 1 1 Einleitung .................................................................................................................. 2 1.1. Problemstellung und Relevanz der Forschungsfragen...................................... 5 1.2. Aufbau der Arbeit ............................................................................................ 13 2 Theoretische Grundlage: Folter ............................................................................. 14 2.1. Zur Definition von Folter ................................................................................. 14 2.1.1. Die Folter als Rechtsmittel ....................................................................... 16 2.1.2. Folter – eine rechtswissenschaftliche Definition ..................................... 18 2.1.3. Natur der Folter ........................................................................................ 19 2.1.4. Ziel der Folter ........................................................................................... 21 2.1.5. Folter - ein rein öffentlicher Akt? -

Michel Foucault's Lecture at the Collège De France on Neo-Liberal Governmentality

1 "The Birth of Bio-Politics" – Michel Foucault's Lecture at the Collège de France on Neo-Liberal Governmentality From 1970 until his death in 1984, Michel Foucault held the Chair of "History of Systems of Thought" at the Collège de France.1 In his public lectures delivered each Wednesday from early January through to the end of March/beginning of April, he reported on his research goals and findings, presenting unpublished material and new conceptual and theoretical research tools. Many of the ideas developed there were later to be taken up in his various book projects. However, he was in fact never to elaborate in writing on some of the research angles he presented there. Foucault's early and unexpected death meant that two of the key series of lectures have remained largely unpublished ever since, namely the lectures held in 1978 ("Sécurité, territoire et population") and in 1979 ("La naissance de la biopolitique").2 These lectures focused on the "genealogy of the modern state" (Lect. April 5, 1978/1982b, 43). Foucault deploys the concept of government or "governmentality" as a "guideline" for the analysis he offers by way of historical reconstructions embracing a period starting from Ancient Greek through to modern neo-liberalism (Foucault 1978b, 719). I wish to emphasize two points here, as they seem important for an adequate assessment of the innovative potential of the notion of governmentality. First of all, the concept of governmentality demonstrates Foucault's working hypothesis on the reciprocal constitution of power techniques and forms of knowledge. The semantic linking of governing ("gouverner") and modes of thought ("mentalité") indicates that it is not possible to study the technologies of power without an analysis of the political rationality underpinning them. -

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION in the Period Immediately Following The

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION In the period immediately following the close of the Civil War, philanthropic endeavors were undertaken to reconstruct secessionist states, establish wide-scale peace among still- hostile factions, and develop efforts to enact social, legal, and educational support. This philanthropic era is characterized by the activities of a number of individual, denominational, organizational, including state and federal supporters that were subsequently responsible for engendering a Negro College Movement, which established institutions for providing freed slaves, and later, Negroes with advanced educational degrees. This dissertation studied: the genesis, unfolding, contributions, and demise issues in conjunction with the social, economic, and political forces that shaped one such institution in Harper’s Ferry (Jefferson County), West Virginia: Storer College, which was founded in 1865 as an outgrowth of several mission schools. By an Act of Congress, in 1868, the founders of Storer College initially were granted temporary use of four government buildings from which to create their campus.1 Over the next 90 years, until its closure in 1955, the college underwent four distinct developmental phases: (a) Mission School [Elementary], (b) Secondary Division, (c) a Secondary Expansion, and (d) Collegiate. Even today—as a result of another Act of Congress—it continues to exist, albeit in altered form: in 1960, the National Park Service branch of the United States Department of the Interior was named the legal curator of the 1 United States. Congress. Legislative, Department of War. An Act Providing for the Sale of Lands, Tenements, and Water Privileges Belonging to the United States at or Near Harpers Ferry, in the County of Jefferson, West Virginia (1868).