Second Life for Ponds Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WETLAND PLANTS – Full Species List (English) RECORDING FORM

WETLAND PLANTS – full species list (English) RECORDING FORM Surveyor Name(s) Pond name Date e.g. John Smith (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 (see your map) e.g. SP 1235 4325 (see your map) METHOD: wetland plants (full species list) survey Survey a single Focal Pond in each 1km square Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value using plants, by recording all wetland plant species present within the pond’s outer boundary. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from the extent of wetland vegetation (for example a ring of rushes growing at the pond’s outer edge), or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. After your survey please enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Stonewort, Bristly (Chara hispida) Bistort, Amphibious (Persicaria amphibia) Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia) Stonewort, Clustered (Tolypella glomerata) Crystalwort, Channelled (Riccia canaliculata) Arrowhead, Canadian (Sagittaria rigida) Stonewort, Common (Chara vulgaris) Crystalwort, Lizard (Riccia bifurca) Arrowhead, Narrow-leaved (Sagittaria subulata) Stonewort, Convergent (Chara connivens) Duckweed , non-native sp. -

ZNIEFF Continentales : Liste Des Espèces De Flore Déterminantes En Région PACA

Actualisation de l’inventaire des Zones Naturelles d’Intérêt Écologique, Faunistique et Floristique (ZNIEFF) de Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur ZNIEFF continentales : liste des espèces de flore déterminantes en région PACA Version du 28/07/2016 Référentiel taxonomique : TAXREF v5.0 Les alismatales PHYLUM CLASSE ORDRE FAMILLE CD_REF RANG NOM_VALIDE Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Alismataceae 85486 ES Baldellia ranunculoides (L.) Parl., 1854 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Alismataceae 160264 SSES Damasonium alisma Mill. subsp. polyspermum (Coss.) Maire Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Alismataceae 119860 ES Sagittaria sagittifolia L., 1753 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Butomaceae 87136 ES Butomus umbellatus L., 1753 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Hydrocharitaceae 103120 ES Hydrocharis morsus-ranae L., 1753 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Hydrocharitaceae 128504 ES Vallisneria spiralis L., 1753 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Juncaginaceae 141931 SSES Triglochin bulbosum subsp. barrelieri (Loisel.) Rouy, 1912 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Juncaginaceae 127546 ES Triglochin maritimum L., 1753 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Potamogetonaceae 81869 ES Althenia filiformis Petit, 1829 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Potamogetonaceae 115228 ES Potamogeton alpinus Balb., 1804 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Potamogetonaceae 115237 ES Potamogeton coloratus Hornem., 1813 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Potamogetonaceae 115258 ES Potamogeton gramineus L., 1753 Plantae Equisetopsida Alismatales Potamogetonaceae 115296 ES Potamogeton -

Buried Alive Aquatic Plants Survive in 'Ghost Ponds' Under Agricultural Fields

Biological Conservation 212 (2017) 105–110 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Buried alive: Aquatic plants survive in ‘ghost ponds’ under agricultural fields MARK ⁎ Emily Aldertona, ,1, Carl Derek Sayera, Rachael Daviesb, Stephen John Lambertc, Jan Christoph Axmachera a Pond Restoration Research Group, Environmental Change Research Centre (ECRC), Department of Geography, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK b Millennium Seedbank, Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, Ardingly, Sussex RH17 6TN, UK c School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Norfolk, NR4 7TJ, UK ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The widespread loss of wetlands due to agricultural intensification has been highlighted as a major threat to Biodiversity aquatic biodiversity. However, all is not lost as we reveal that the propagules of some aquatic species could Palaeoecology survive burial under agricultural fields in the sediments of ‘ghost ponds’ - ponds in-filled during agricultural land Propagules consolidation. Our experiments showed at least eight aquatic macrophyte species to germinate from seeds and Restoration oospores, following 50–150 years of dormancy in the sediments of ghost ponds. This represents a significant Resurrection proportion of the expected macrophyte diversity for local farmland ponds, which typically support between 6 Seed bank and 14 macrophyte species. The rapid (< 6 months) re-colonisation of resurrected ghost ponds by a diverse aquatic vegetation similarly suggests a strong seed-bank influence. Ghost ponds represent abundant, dormant time capsules for aquatic species in agricultural landscapes around the globe, affording opportunities for en- hancing landscape-scale aquatic biodiversity and connectivity. While reports of biodiversity loss through agri- cultural intensification dominate conservation narratives, our study offers a rare positive message, demon- strating that aquatic organisms survive prolonged burial under intensively managed agricultural fields. -

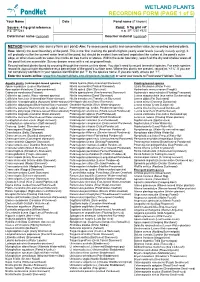

Pondnet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5)

WETLAND PLANTS PondNet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5) Your Name Date Pond name (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 e.g. SP 1235 4325 Determiner name (optional) Voucher material (optional) METHOD (complete one survey form per pond) Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value, by recording wetland plants. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from wetland vegetation like rushes at the pond’s outer edge, or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put ’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. Enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ or send your results to Freshwater Habitats Trust. Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Nitella hyalina (Many-branched Stonewort) Floating-leaved species Apium inundatum (Lesser Marshwort) Nitella mucronata (Pointed Stonewort) Azolla filiculoides (Water Fern) Aponogeton distachyos (Cape-pondweed) Nitella opaca (Dark Stonewort) Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (Frogbit) Cabomba caroliniana (Fanwort) Nitella spanioclema (Few-branched Stonewort) Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (Floating Pennywort) Callitriche sp. -

Wetland Plants Survey Form

WETLAND PLANTS PondNet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5) Your Name Date Pond name (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 e.g. SP 1235 4325 Determiner name (optional) Voucher material (optional) METHOD (complete one survey form per pond) Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value, by recording wetland plants. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from wetland vegetation like rushes at the pond’s outer edge, or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. Enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ or send your results to Freshwater Habitats Trust. Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Stonewort, Bearded (Chara canescens) Floating-leaved species Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia) Stonewort, Bristly (Chara hispida) Bistort, Amphibious (Persicaria amphibia) Arrowhead, Canadian (Sagittaria rigida) Stonewort, Clustered (Tolypella glomerata) Crystalwort, Channelled (Riccia canaliculata) Arrowhead, Narrow-leaved (Sagittaria subulata) Stonewort, Common (Chara vulgaris) Crystalwort, Lizard (Riccia bifurca) Awlwort (Subularia aquatica) Stonewort, Convergent (Chara connivens) Duckweed, non-native sp. -

Written Representation Expert Report

Interested Party ID: 20025904 THE SIZEWELL C PROJECT NNB Generation Co (SZC) Ltd EN010012 WRITTEN REPRESENTATION EXPERT REPORT A critical review of SZC Co’s site characterisation, impact assessment, and proposals for impact mitigation, in relation to the risks posed to the ecohydrological integrity of Sizewell Marshes SSSI Dr Rob Low, Dr David Mould, Jonathan Graham [email protected] Acknowledgements Suffolk Coastal Friends of the Earth would like to thank Suffolk Wildlife Trust, the RSPB and the Minsmere Levels Stakeholder Group for their kind assistance during the preparation of this report. 2 A critical review of SZC Co.’s site characterisation, impact assessment, and proposals for impact mitigation, in relation to the risks posed to the ecohydrological integrity of Sizewell Marshes SSSI by the development of Sizewell C Nuclear Power Station, as proposed. Authored by Dr. Rob Low (lead), Dr. David Mould and Mr. Jonathan Graham. This Written Representation to the Sizewell C hearing concerns the serious risks to the viability of wetland plant communities and species of interest within Sizewell Marshes Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), leading from the proposals to develop the Sizewell C Nuclear Power Station, brought forward by NNB Generation Company (SZC) Ltd (SZC Co. hereafter). It has been written on behalf of Friends of the Earth and Suffolk Wildlife Trust by Dr Rob Low, Dr David Mould and Jon Graham. 1 Names, qualifications and experience 1.1 Dr. Rob Low I am Dr. Rob Low, and I am the Managing Director of Rigare Ltd (Abergavenny), a company which provides expert services and advice on the subjects of wetland ecohydrology and hydrogeology. -

Adatok a Színes Békaszőlő (Potamogeton Coloratus) Hazai

http://kitaibelia.unideb.hu/ ISSN 2064-4507 (Online) ● ISSN 1219-9672 (Print) © 2016, Department of Botany, University of Debrecen, Hungary 22 (1): 77–83.; 2017 DOI: 10.17542/kit.22.77 Adatok a színes békaszőlő ( Potamogeton coloratus ) hazai előfordulásához MESTERHÁZY Attila 1, VIDÉKI Róbert 2, LUKÁCS Balázs András 3, MÉSZÁROS András 4 & MOLNÁR V. Attila 5 (1) Hortobágyi Nemzeti Park Igazgatóság, H-4024 Debrecen, Sumen u 2. (2) Doronicum Kft., H-9794 Felsőcsatár, Petőfi u. 13. (3) MTA Ökológiai Kutatóközpont DKI, Tisza-kutató Osztály, H-4026, Debrecen, Bem tér 18/C; (4) Balaton-felvidéki Nemzeti Park Igazgatóság, H-8229 Csopak, Kossuth L. u. 16. (5) Debreceni Egyetem TTK, Növénytani Tanszék, H-4032 Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1.; [email protected] Recent Hungarian distribution of Potamogeton coloratus Abstract – The distribution of fen pondweed ( Potamogeton coloratus ) restricted to Europe where it is one of the rarest and most threatened pondweed species. In Hungary, former data of fen pondweed originated mostly from thermal and karstic springs. Due to intensive bauxite mining activity in the edge of the Transdanubian Mountain Range (NW Hungary) these springs dried up by the end of the 20 th century, and it caused the temporal extinction of the species. After the ceasing of mining activity many of the former karstic springs have regenerated and several fen pondweed populations have re- established. In this paper we summarized 18 population data of fen pondweed collected between 1999 and 2016. Many of them were formerly registered in the 19 th century too. Most of the new and re- discovered populations were found in karstic springs or in artificial and natural lakes in the vicinity of these springs. -

HANDY GUIDE to AQUATIC PLANTS in IRELAND Waterlilies Duckweeds

HANDY GUIDE TO AQUATIC PLANTS IN IRELAND Floating: Nymphaea, Nuphar, Nymphoides, Potamogeton, Lemna Rooted rosettes: Isoetes, Lobelia, Littorella, Subularia Ribbon-leaves: Sagittaria, Stratiotes, Potamogeton, Sparganium Simple alternate: Potamogeton, Lagarosiphon, Persicaria, Fontinalis antipyretica Opposite pairs: Crassula, Callitriche, Simple whorls: Elodea (3), Egeria (4-6), Hydrilla (4-5) Elodea Ceratophyllum Hottonia Egeria Ranunculus Myriophyllum Lagarosiphon Utricularia Hippuris, Hydrilla Other Compound leaves: Apium inundatum (Bipinnate, fine hair like branches) Oenanthe aquatica (Tripinnate; narrow leaflets, becoming emergent and cow- parsley-like) Waterlilies Nuphar lutea (2ndry veins arising along midrib; Yellow flwrd; over-wintering leaves lettuce like, petiole angular) Nymphaea alba (2ndry veins arising from petiole; White flwrd; petiole round, margin entire) Nymphoides peltata (Yellow flwrd; margin scalloped). – an alien invasive species Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (white flwd; leaves small, thick, rounded, margin smooth) Duckweeds Lemna gibba (Fat duckweed – bead-like) Lemna minor (2-4 mm across) Lemna minuta (1 mm across) Lemna trisulca (Ivy-leaved, usually submerged, sitting on plants or sediment) Spirodela polyrhiza (4-5 mm across; 2-4 roots) Starworts Submerged leaves long and linear, floating leaves blunt, ovate Callitriche brutia (leaves expanded at tip and notched) Callitriche hamulata (leaves expanded at tip and notched) Callitriche hermaphroditica (fruits winged) Callitriche obtusangula Callitriche palustris Callitriche -

Aquatic Plants Checklist

CHECKLIST OF SUBMERGED AND FLOATING AQUATIC PLANTS - BEDS, OLD CAMBS, HUNTS, NORTHANTS AND PETERBOROUGH Scientific name Common Name Beds old Cambs Hunts Northants and Ellenberg P'boro N PLANTS WITH SIMPLE, MORE OR LESS LINEAR UNDERWATER LEAVES; FLOATING OR EMERGENT LEAVES MAY BE BROADER Linear leaves only Eleogiton fluitans Floating Club-rush absent rare very rare extinct 2 Juncus bulbosus Bulbous Rush very rare rare rare very rare 2 Lagarosiphon major Curly Waterweed occasional occasional very rare very rare 6 + Potamogeton acutifolius Sharp-leaved Pondweed absent absent absent extinct 6 Potamogeton berchtoldii Small Pondweed rare occasional rare occasional 5 Potamogeton compressus Grass-wrack Pondweed extinct rare rare occasional 4 + Potamogeton friesii Flat-stalked Pondweed very rare occasional rare very rare 5 Potamogeton obtusifolius Blunt-leaved Pondweed very rare absent absent rare 5 + Potamogeton pectinatus Fennel Pondweed frequent frequent frequent frequent 7 + Potamogeton pusillus Lesser Pondweed occasional occasional occasional occasional 6 Potamogeton trichoides Hairlike Pondweed extinct occasional very rare very rare or extinct 6 Ruppia cirrhosa Spiral Tasselweed absent extinct absent absent 5 Zannichellia palustris Horned Pondweed occasional frequent occasional frequent 7 + Zostera marina Eelgrass absent very rare or extinct absent absent 6 Broad-leaved floating rosettes/leaves may be present Callitriche brutia ssp. hamulata Intermediate Water-starwort occasional absent very rare occasional 5 Callitriche obtusangula Blunt-fruited -

Synonymique De La Flore De Suisse Synonymie-Index Der Schweizer Flora Indice Sinonimico Della Flora Della Svizzera

Documenta Floristicae Helvetiae N° 2 Index synonymique de la Flore de Suisse et territoires limitrophes (ISFS) Synonymie-Index der Schweizer Flora und der angrenzenden Gebiete (SISF) Indice sinonimico della Flora della Svizzera e territori limitrofi (ISFS) D. Aeschimann & C. Heitz avec la collaboration de – in Zusammenarbeit mit – con la collaborazione di C. Latour, P. Perret & B. Bäumler 2ème édition – 2te Auflage – 2da edizione Genève 2005 Abréviations Statut des noms latins Ouvrages de référence aggr. = [lat.: aggregatum], agrégat 1. Les noms Acceptés, retenus par les auteurs de l’ISFS. Ils Referenzwerke auct. = [lat.: auctorum], des auteurs figurent en gras (ex.: Sparganium angustifolium Michx.). Opere di riferimento s.l. = [lat.: sensu lato], au sens large 2. Les noms Synonymes, qui sont en italiques (ex.: Sparganium AB = Aeschimann, D. & H. M. Burdet (2005). Flore de la s.str. = [lat.: sensu stricto], au sens strict minimum Wallr.). Suisse et des territoires limitrophes. Le Nouveau Binz. subsp. = [lat.: subspecies], sous-espèce 3. Les noms appliqués à des taxons Inclus, qui correspondent Ed. 3. Haupt, Berne. var. = [lat.: varietas], variété à des entités taxonomiques étroites, incluses dans un taxon Ξ = xénophyte plus large au nom le plus souvent accepté. Ils sont cités en BH = Binz, A. & Ch. Heitz (1990). Schul- und Exkursions- X = pas présent en Suisse gras et italiques (ex.: Sparganium erectum subsp. oocarpum flora für die Schweiz. Ed. 19. Schwabe, Basel. ? = présence en Suisse douteuse, ou sporadique (Čelak.) Domin). FH = Lauber, K. & G. Wagner (2001). Flora Helvetica. 4. Les noms en Regroupant plusieurs autres. Ils figurent en Explications complètes aux pp. 5-6. Ed. -

Redalyc.Potamogeton Schweinfurthii in the Iberian Peninsula

Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid ISSN: 0211-1322 [email protected] Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas España Aymerich, Pere; Kaplan, Zdenek; Guardiola, Moisès; Petit, Albert; Schwarzer, Udo Potamogeton schweinfurthii in the Iberian Peninsula Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid, vol. 69, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2012, pp. 187-192 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=55625159002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 2297 Potamogeton.af_Anales 69(2).qxd 14/12/2012 12:35 Página 187 Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid 69(2): 187-192, julio-diciembre 2012. ISSN: 0211-1322. doi: 10.3989/ajbm. 2297 Potamogeton schweinfurthii in the Iberian Peninsula Pere Aymerich1*, Zdenek Kaplan2, Moisès Guardiola3, Albert Petit3 & Udo Schwarzer4 1C/Barcelona, 29, E-08600 Berga, Spain, [email protected] 2Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; [email protected] 3Grup de Geobotànica i Cartografia de la Vegetació, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Diagonal 645, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain [email protected]; [email protected] 4Apartado 1020, P-8671-909 Aljezur, Portugal; [email protected] Abstract Resumen Aymerich, P., Kaplan, Z., Guardiola, M., Petit, A. & Schwarzer, U. 2012. Aymerich, P., Kaplan, Z., Guardiola, M., Petit, A. & Schwarzer, U. 2012. Potamogeton schweinfurthii in the Iberian Peninsula. Anales Jard. Bot. Potamogeton schweinfurthii en la Península Ibérica. -

Die Makrophyten Des Senftenberger Sees

88 NATURSCHUTZ UND LANDSCHAFTSPFLEGE IN BRANDENBURG 18 (3) 2009; 88-95 IM SENFTENBERGER SEE VERMISCHT SICH SAURES, CARBONAT- UND NÄHRSTOFFARMES WASSER MIT NEUTRALEM, CARBONAT- UND NÄHRSTOFFREICHEM WASSER AUS DER SCHWARZEN ELSTER. DIESE MISCHUNG FÜHRT ZU EINER EINZIGARTIGEN ZUSAMMENSETZUNG DER MAKROPHYTENVEGETATION. KLAUS VAN DE WEYER, JÜRGEN NEUMANN, WERNER PIETSCH, JENS PÄZOLT, PATRICK TIGGES Die Makrophyten des Senftenberger Sees Schlagwörter: Tagebauseen, Makrophyten, Juncus bulbosus, Littorella uniflora, Potamogeton nodosus, Characeae, Chara braunii, Wasserrahmenrichtlinie Zusammenfassung Insbesondere in weichen, karbonatarmen Makrophyten wurden Artenzusammensetz- Gewässern wirkt der pH-Wert als weiterer ungen von Weich- und Hartwasserarten Die aquatischen Makrophyten im Tage- differenzierender Faktor. So finden sich z.B. sowie von oligo- und eutraphenten Arten bausee Senftenberger See wurden im August in sauren Seen Arten wie Juncus bulbosus, beobachtet, die nachfolgend dargestellt wer- 2007 durch Tauchgänge an 11 Transekten Sphagnum spp. bzw. Utricularia minor. Un- den. Da zudem ältere Aufzeichnungen von untersucht. An ausgewählten Standorten terschiede sind hierbei zwischen natürlichen PIETSCH (1990a, 1998) vorliegen, kann auch wurde die physikalisch-chemische Beschaf- Seen und Tagebauseen zu beobachten auf die Entwicklung der Makrophyten im fenheit der Wasserkörper und Gewässersedi- (PIETSCH 1973, 1995). Weiterhin ist die Tro- Senftenberger See seit dem Jahr 1968 einge- mente erfasst. Aufgrund der speziellen phie von großer Bedeutung. In karbonatrei- gangen werden. physikalisch-chemischen Bedingungen kom- chen bayerischen Seen finden sich z.B. men im Senftenberger See sowohl Hart- wie Potamogeton coloratus und Chara hispida auch Weichwasser-Makrophyten vor. Deren in nährstoffarmen bzw. gering belasteten 2 Untersuchungsgebiet Bestandsentwicklung von 1968-2007 wird Abschnitten, während z.B. Potamogeton beschrieben. Bei der Mehrzahl der Makro- nodosus und P.