Mary Alice Evatt and Australian Modernist Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian & New Zealand

Australian & New Zealand Art Collectors’ List No. 176, 2015 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke Street) Kensington (Sydney) NSW Ph: (02) 9663 4848 Email: [email protected] Web: joseflebovicgallery.com 1. Ernest E. Abbott (Aust., JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY 1888-1973). The First Sheep Established 1977 Station [Elizabeth Farm], c1930s. Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney) NSW Drypoint, titled, annot ated “Est. by John McArthur [sic], 1793. Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia Final” and signed in pencil in Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 lower mar gin, 18.9 x 28.8cm. Small stain to image lower centre, Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com old mount burn. Open: Mon. to Sat. by appointment or by chance. ABN 15 800 737 094 $770 Member: Aust. Art & Antique Dealers Assoc. • Aust. & New Zealand Assoc. of English-born printmaker, painter and art teacher Abbott migrated to Aus- Antiquarian Booksellers • International Vintage Poster Dealers Assoc. • Assoc. of tralia in 1910, eventually settling in International Photography Art Dealers • International Fine Print Dealers Assoc. Melbourne, Victoria, after teaching art at Stott’s in South Australia. Largely self-taught, he took up drypoint etching, making his own engraving tools. Ref: DAAO. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 176, 2015 2. Anon. Sydney From Kerosene Bay, c1914. Watercolour, titled in pencil lower right, 22.8 x 32.9cm. Foxing, old mount burn. Australian & New Zealand Art $990 Possibly inspired by Henry Lawson’s On exhibition from Wednesday, 1 April to Saturday, 16 May. poem, Kerosene Bay written in 1914: “Tis strange on such a peaceful day / All items will be illustrated on our website from 11 April. -

Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA

arts Article Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA Marie Geissler Faculty of Law Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia; [email protected] Received: 19 February 2019; Accepted: 28 April 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: This paper explores how the appeal of the imagery of the Arnhem Land bark painting and its powerful connection to land provided critical, though subtle messaging, during the post-war Australian government’s tourism promotions in the USA. Keywords: Aboriginal art; bark painting; Smithsonian; Baldwin Spencer; Tony Tuckson; Charles Mountford; ANTA To post-war tourist audiences in the USA, the imagery of Australian Aboriginal culture and, within this, the Arnhem Land bark painting was a subtle but persistent current in tourism promotions, which established the identity and destination appeal of Australia. This paper investigates how the Australian Government attempted to increase American tourism in Australia during the post-war period, until the early 1970s, by drawing on the appeal of the Aboriginal art imagery. This is set against a background that explores the political agendas "of the nation, with regards to developing tourism policies and its geopolitical interests with regards to the region, and its alliance with the US. One thread of this paper will review how Aboriginal art was used in Australian tourist designs, which were applied to the items used to market Australia in the US. Another will explore the early history of developing an Aboriginal art industry, which was based on the Arnhem Land bark painting, and this will set a context for understanding the medium and its deep interconnectedness to the land. -

Download This PDF File

Illustrating Mobility: Networks of Visual Print Culture and the Periodical Contexts of Modern Australian Writing VICTORIA KUTTAINEN James Cook University The history of periodical illustration offers a rich example of the dynamic web of exchange in which local and globally distributed agents operated in partnership and competition. These relationships form the sort of print network Paul Eggert has characterised as being shaped by everyday exigencies and ‘practical workaday’ strategies to secure readerships and markets (19). In focussing on the history of periodical illustration in Australia, this essay seeks to show the operation of these localised and international links with reference to four case studies from the early twentieth century, to argue that illustrations offer significant but overlooked contexts for understanding the production and consumption of Australian texts.1 The illustration of works published in Australia occurred within a busy print culture that connected local readers to modern innovations and technology through transnational networks of literary and artistic mobility in the years also defined by the rise of cultural nationalism. The nationalist Bulletin (1880–1984) benefited from a newly restricted copyright scene, while also relying on imported technology and overseas talent. Despite attempts to extend the illustrated material of the Bulletin, the Lone Hand (1907–1921) could not keep pace with technologically superior productions arriving from overseas. The most graphically impressive modern Australian magazines, the Home (1920–1942) and the BP Magazine (1928–1942), invested significant energy and capital into placing illustrated Australian stories alongside commercial material and travel content in ways that complicate our understanding of the interwar period. One of the workaday practicalities of the global book trade which most influenced local Australian producers and consumers prior to the twentieth century was the lack of protection for international copyright. -

Ii: Mary Alice Evatt, Modern Art and the National Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cultivating the Arts Page 394 CHAPTER 9 - WAGING WAR ON THE ESTABLISHMENT? II: MARY ALICE EVATT, MODERN ART AND THE NATIONAL ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES The basic details concerning Mary Alice Evatt's patronage of modern art have been documented. While she was the first woman appointed as a member of the board of trustees of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, the rest of her story does not immediately suggest continuity between her cultural interests and those of women who displayed neither modernist nor radical inclinations; who, for example, manned charity- style committees in the name of music or the theatre. The wife of the prominent judge and Labor politician, Bert Evatt, Mary Alice studied at the modernist Sydney Crowley-Fizelle and Melbourne Bell-Shore schools during the 1930s. Later, she studied in Paris under Andre Lhote. Her husband shared her interest in art, particularly modern art, and opened the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society in Melbourne 1939, and an exhibition in Sydney in the same year. His brother, Clive Evatt, as the New South Wales Minister for Education, appointed Mary Alice to the Board of Trustees in 1943. As a trustee she played a role in the selection of Dobell's portrait of Joshua Smith for the 1943 Archibald Prize. Two stories thus merge to obscure further analysis of Mary Alice Evatt's contribution to the artistic life of the two cities: the artistic confrontation between modernist and anti- modernist forces; and the political career of her husband, particularly knowledge of his later role as leader of the Labor opposition to Robert Menzies' Liberal Party. -

Fantin-Latour in Australia

Ann Elias Fantin-Latour in Australia Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Citation: Ann Elias, “Fantin-Latour in Australia,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn09/fantin-latour-in-australia. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Elias: Fantin-Latour in Australia Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Fantin-Latour in Australia by Ann Elias Introduction Australia is described as "a country of immigration"[1] and its non-indigenous people as "a cutting from some foreign soil."[2] This is an apt metaphor for a postcolonial population cut from British stock, then transplanted to the Antipodes in the eighteenth century, and augmented, changed, and challenged throughout the nineteenth century by migrations of European (British and other) and Asian nationals. The floral metaphor can be extended by speaking of migration and settlement in terms of grafting, hybridizing, and acclimatizing. In the early part of the nineteenth century, settlers viewed the landscape of Australia— including all flora and fauna—as "wild and uncivilised, almost indistinguishable from the Indigenous inhabitants."[3] The introduction, therefore, of flora and fauna from Britain was an attempt "to induce an emotional bond between Australian colonies and the mother country." [4] So too was the importation of art and artifacts from Britain, France, and other European countries, which was a further effort to maintain ties with the Old World. -

Shadows of Another Dimension: a Bridge Between Mathematician and Artist Janelle Robyn Humphreys University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year 2009 Shadows of another dimension: a bridge between mathematician and artist Janelle Robyn Humphreys University of Wollongong Humphreys, Janelle Robyn, Shadows of another dimension: a bridge between mathe- matician and artist, Doctor of Creative Arts thesis, School of Art and Design - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3079 This paper is posted at Research Online. Shadows of another dimension: A bridge between mathematician and artist A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Creative Arts from University of Wollongong by Janelle Robyn Humphreys BA (Mathematics and physics). Macquarie University Advanced Diploma of Fine Arts. Northern Sydney Institute TAFE NSW Master of Studio Art (hons.). Sydney College of the Arts Faculty of Creative Arts School of Art and Design 2009 1 CERTIFICATION I, Janelle Robyn Humphreys, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Janelle Robyn Humphreys 15 March 2009 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of figures……………………………………………………………………………5 List of tables……………………………………………………………………………..8 -

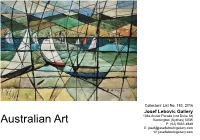

Australian Art

Australian Art Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke Street) Kensington (Sydney) NSW Ph: (02) 9663 4848; Fax: (02) 9663 4447 Email: [email protected] Web: www.joseflebovicgallery.com JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY Established 1977 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney) NSW Post: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia Tel: (02) 9663 4848 • Fax: (02) 9663 4447 • Intl: (+61-2) Email: [email protected] • Web: joseflebovicgallery.com Open: Wed to Fri by appointment, Sat 12-5pm • ABN 15 800 737 094 Member of • Association of International Photography Art Dealers Inc. International Fine Print Dealers Assoc. • Australian Art & Antique Dealers Assoc. 1. Anon. Antipodeans - Victorian Artists Society, 1959. Lithograph, inscribed in ink in an unknown hand verso, 35.3 x 43cm COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 145, 2010 (paper). Some stains and soiling overall. $1,250 Text continues “[On show] 4th August to 15th August. Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd, David 2. Normand Baker (Australian, 1908- Australian Art Boyd, John Brack, Bob Dickerson, John Perceval, 1955). [George Chew Lee’s Produce Store], Clifton Pugh, Bernard Smith.” Inscription reads c1930. Pencil drawing with colour notations, “Dear Sir, Would it be possible if you could please put this poster in your window. Yours sincerely, accompanied by a handwritten note of Compiled by Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Lenka Miklos, Mariela Brozky The Antipodeans. P.S. The Antipodeans would be authenticity, 34 x 24.2cm. Slight foxing, On exhibition from Saturday, 16 October to Saturday, 20 November and thankful.” minor soiling to edges. The artists mentioned in this poster formed the $880 on our website from 23 October. Antipodean group to show work by figurative The note reads “I declare that this pencil sketch All items have been illustrated in this catalogue. -

Australian Art P: (02) 9663 4848 E: [email protected] W: Joseflebovicgallery.Com 1

Collectors’ List No. 183, 2016 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW Australian Art P: (02) 9663 4848 E: [email protected] W: joseflebovicgallery.com 1. Anon. [Gnome Fairies], c1920s. Gouache JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY with ink, partially obscured initials “A.J.[?]” in Established 1977 gouache lower right, 21.6 x 17.9cm. Laid down Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) on original backing. $1,350 Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney) NSW In the style of Ida Rentoul Outhwaite (Aust., 1888-1960). Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com Open: Monday to Saturday by chance or please make an appointment. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 183, 2016 Australian Art 2. John Baird (Aust., 1902-c1988). [Young Wo man], On exhibition from Wed., 6 July to Sat., 26 August. c1930. Pencil drawing, signed lower right, 30 x 7cm All items will be illustrated on our website from 22 July. (image). $880 Prices are in Australian dollars and include GST. Exch. rates as at Painter and cartoonist John Baird was a foundation member of time of printing: AUD $1.00 = USD $0.74¢; UK £0.52p the Society of Australian Black and White Artists. Baird became known for his oil paintings, especially for his portrait of ‘Model © Licence by VISCOPY AUSTRALIA 2016 LRN 5523 of the Year’ Patricia “Bambi” Tuckwell in 1946. Ref: DAAO. Compiled by Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Dimity Kasz, Takeaki Totsuka, Lenka Miklos NB: Artists’ birth and death dates in this list are based on currently available references and information from institutions, which can vary. -

Swinburne Research Bank

Swinburne Research Bank http://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au Jackson, Simon (2003). Industrial design journals in Australia. Australiana magazine. 25(2) : 45-46. Copyright © 2003 Simon Jackson. This is the author’s version of the work. It is posted here with permission of the publisher for your personal use. No further distribution is permitted. If your Library has a subscription to this journal, you may also be able to access the published version via the library catalogue. Industrial Design journals in Australia Simon Jackson Journals devoted to the fine arts and architecture have flourished in Australia. Rarer has been the brave publisher willing to promote industrial design. While Australian designers have long had access to international design journals, local publications have been fewer in number. Of these, the influence of the Sydney Ure Smith journals, The Home and Art in Australia has been widely acknowledged. In both, however, objects of design are only discussed in terms of ‘taste’ and decorating, avoiding the more prosaic associations of design with industry. Less well known are another two Ure Smith publications which focused on design and manufacturing issues. Australia: National Journal was first published on the cusp of WWII and strongly promoted industrial design and manufacturing. Ure Smith’s plans for this pioneering new journal reflect a country recognising a need to further industrialise: Industry will be featured, because in industry our greatest activity is taking place. Our development of new industries will need to be swift and sure, and it is as well for our public to be informed regularly on the subject.. -

The La Trobe Journal No. 93-94 September 2014 End Pages

Endnotes Not Lost, Just Hiding: Eugene von Guérard’s first Australian sketchbooks (Pullin) I am grateful to John Arnold, editor of the La Trobe Journal, Gerard Hayes, Librarian, Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria, Alice Cannon, Senior Paper Conservator, State Library of Victoria, and Börries Brakebusch, Conservator, Brakebusch Conservation Studio, Düsseldorf, for their generous assistance with the research for this paper. In particular I would like to thank Anna Brooks, Senior Paper Conservator, State Library of New South Wales, for her professional advice and commitment to the project. I am grateful to Anna for making the trip to Melbourne, with the von Guérard ‘Journal’, and to the State Library of New South Wales for making this possible. I thank Doug Bradby, Buninyong, for sharing his knowledge of Ballarat and its goldfields’ history with me and as always I thank my partner, Richard de Gille for his assiduous proofreading of the document. I wish to acknowledge and thank the State Library of Victoria for its support of my research with a State Library of Victoria Creative Fellowship (2012-2013). 1 Von Guérard reached ‘journey’s end’, Melbourne, on 28 December 1852. The site, known as Fitzroy Square from 1848, became the Fitzroy Gardens in 1862. George McCrae (b.1833) recalled that in his boyhood the area was clothed in one dense gum forest’, Gary Presland, The Place for a Village: how nature has shaped the city of Melbourne, Melbourne: Museum Victoria, 2008, pp. 122-4. 2 The tally of the number of drawings in the collection is higher when drawings on each side of a sheet are counted as individual drawings. -

ANN ELIAS Flower Men: the Australian Canon and Flower Painting 1910-1935

Ann Elias, Flower Men: The Australian Canon and Flower Painting 1910-1935 ANN ELIAS Flower Men: The Australian Canon and Flower Painting 1910-1935 Abstract Historical studies of Hans Heysen, George Lambert, Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton concentrate on paintings of landscape and people. Less well known are their paintings of flowers, which take the form of still-life painting or adjuncts to figure painting, such as portraits. While these artists are famous for the masculine way they approached masculine themes, and flower painting represents a stereotypically feminine subject, I argue that by making flowers their object of study, they intended to define and differentiate femininity from masculinity in an era of the ‘New Woman’. Sex and gender are central to the subject of flower painting and are important for discussions about the work produced by all four men, although sex is often camouflaged behind the innocence of naturalistically painted flowers. Fig.1. Tom Roberts, Roses, 1911, oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm, Gift of Mr F.J.Wallis 1941, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Photograph: Jenni Carter. Introduction: The Rough and the Pretty In 1996, Humphrey McQueen remarked on the striking contrast in Tom Roberts’ output between the feminine subject of flowers and the masculine subject of landscape: Roses could not have been further removed in subject or mood from the sketches Roberts had been making in the Riverina of masculine work. We have approached the manner of man who could switch between the pretty and the rough.1 This switch between ‘the rough and the pretty’ also applies to Hans Heysen, George Lambert, and Arthur Streeton. -

What's the Matter?: the Object in Australian Art History1

What’s the Matter?: The Object in Australian Art History1 Peter McNeil My paper is an analysis of the vested interest groups that create conflicting histories and narratives, and carries a suggestion that the study of objects in this country falls between a backwards glance and a looking to the future. Australia is a nation that has a problem in dealing with the period before 1830 but constructs its own traditions nonetheless. Where does a nation’s ‘aesthetic identity’ come from – by looking forward to a better material future, or from the past, where a truncated ‘long eighteenth century’ created all manner of problems for Australian connoisseurs and also historians? The construction of the narrative of a material past involved questions of taste and was a process of looking backwards in the immediate post-war period – against ‘Victorianism’, to a more remote European past which barely existed in this continent, and also forwards, beyond the 1950s, considered the nadir of taste for its perceived banality and levelling tendencies. An unsurprising entente has existed between those who wish to re-imagine a more pure Georgian past for this country, a concept that was largely invented in the inter-war years in Britain and the United States at any rate, and those who spurned the perceived vulgarity of contemporary commercial life. In this essay I suggest some of the historiographical issues that inflect the study of objects within Australian art history, firstly for the nineteenth century and then, more briefly, for the twentieth. The possibility of studying a wide range of visual culture within art historical frames has been transformed in the academy since Terry Smith published his ‘Writing the history of Australian art: its past, present and possible future’ in 1983.2 A new interest in affect, materiality, quality, and the sensuous nature of inert objects, as well as the sustainable and indigenous agenda, has transformed the possibility and 1 I thank my Research Assistant Kevin Su for the preparation of this article.