Spirituality and Immorality in Early Sydney Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emu Island: Modernism in Place

Emu Island: Modernism in Place Visual Arts Syllabus Stages 5 - 6 CONTENTS 3 Introduction to Emu Island: Modernism in Place 4 Introduction to education resource Syllabus Links Conceptual framework: Modernism 6 Modernism in Sydney 7 Gerald and Margo Lewers: The Biography 10 Timeline 11 Mud Map Case study – Sydney Modernism Art and Architecture Focus Artists 13 Tony Tuckson 14 Carl Plate 16 Frank Hinder 18 Desiderius Orban 20 Modernist Architecture 21 Ancher House 23 Young Moderns 24 References 25 Bibliography Front Page Margel Hinder Frank Hinder Currawongs Untitled c1946 1945 shale and aluminium collage and gouache on paper 25.2 x 27 x 11 24 x 29 Gift of Tanya Crothers and Darani Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers, 1980 Lewers Bequest Collection Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Margel Hinder Emu Island: Modernism in Place Emu Island: Modernism in Place celebrates 75 years of Modernist art and living. Once the home and studio of artist Margo and Gerald Lewers, the gallery site, was, as it is today - a place of lively debate, artistic creation and exhibitions at the foot of the Blue Mountains. The gallery is located on River Road beside the banks of the Nepean River. Once called Emu Island, Emu Plains was considered to be the land’s end, but as the home of artist Margo and Gerald Lewers it became the place for new beginnings. Creating a home founded on the principles of modernism, the Lewers lived, worked and entertained like-minded contemporaries set on fostering modernism as a holistic way of living. -

Australian Painting from One of the World's Greatest Collectors Offered

Press Release For Immediate Release Melbourne 3 May 2016 John Keats 03 9508 9900 [email protected] Australian Painting from One of the World’s Greatest Collectors Offered for Auction Important Australian & International Art | Auction in Sydney 11 May 2016 Roy de Maistre 1894-1968, The Studio Table 1928. Estimate $60,000-80,000 A painting from the collection of one of world’s most renowned art collectors and patrons will be auctioned by Sotheby’s Australia on 11 May at the InterContinental Sydney. Roy de Maistre’s The Studio Table 1928 was owned by Samuel Courtauld founder of The Courtauld Institute of Art and The Courtauld Gallery, and donor of acquisition funds for the Tate, London and National Gallery, London. De Maistre was one of Australia’s early pioneers of modern art and The Studio Table (estimate $60,000-80,000, lot 127, pictured) provides a unique insight into the studio environment of one of Anglo-Australia’s greatest artists. 1 | Sotheby’s Australia is a trade mark used under licence from Sotheby's. Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd is independent of the Sotheby's Group. The Sotheby's Group is not responsible for the acts or omissions of Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd Geoffrey Smith, Chairman of Sotheby’s Australia commented: ‘Sotheby’s Australia is honoured to be entrusted with this significant painting by Roy de Maistre from The Samuel Courtauld Collection. De Maistre’s works are complex in origins and intricate in construction. Mentor to the young Francis Bacon, De Maistre remains one of Australia’s most influential and enigmatic artists, whose unique contribution to the development of modern art in Australia and Great Britain is still to be fully understood and appreciated.’ A leading exponent of Modernism and Abstraction in Australia, The Studio Table was the highlight of Roy de Maistre’s solo exhibition in Sydney in 1928. -

The Fairfax Women and the Arts and Crafts Movement, 1899-1914

CHAPTER 2 - FROM NEEDLEWORK TO WOODCARVING: THE FAIRFAX WOMEN AND THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT, 1899-1914 By the beginning of the twentieth century, the various campaigns of the women's movement had begun to affect the lives of non-campaigners. As seen in the previous chapter activists directly encouraged individual women who would profit from and aid the acquisition of new opportunities for women. Yet a broader mass of women had already experienced an increase in educational and professional freedom, had acquired constitutional acknowledgment of the right to national womanhood suffrage, and in some cases had actually obtained state suffrage. While these in the end were qualified victories, they did have an impact on the activities and lifestyles of middle-class Australian women. Some women laid claim to an increased level of cultural agency. The arts appeared to fall into that twilight zone where mid-Victorian stereotypes of feminine behaviour were maintained in some respects, while the boundaries of professionalism and leadership, and the hierarchy of artistic genres were interrogated by women. Many women had absorbed the cultural values taken to denote middle-class respectability in Britain, and sought to create a sense of refinement within their own homes. Both the 'new woman' and the conservative matriarch moved beyond a passive appreciation and domestic application of those arts, to a more active role as public promoters or creators of culture. Where Miles Franklin fell between the two stools of nationalism and feminism, the women at the forefront of the arts and crafts movement in Sydney merged national and imperial influences with Victorian and Edwardian conceptions of womanhood. -

Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2013-228 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989 — section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the associated plan. Ben Ponton Delegate of the Minister 04 September 2013 Page 1 of 7 Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Division of Lawson: Henry Lawson’s Australia NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Bellbird Loop Crested Bellbird ‘Bellbird’ is a name given in Australia to two endemic (Oreoica gutturalis) species of birds, the Crested Bellbird and the Bell-Miner. The distinctive call of the birds suggests Bell- Miner the chiming of a bell. Henry Kendall’s poem Bell Birds (Manorina was first published in Leaves from Australian Forests in melanophrys) 1869: And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing, The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing. The silver-voiced bell-birds, the darlings of day-time! They sing in September their songs of the May-time; Billabong Street Word A ‘billabong’ is a pool or lagoon left behind in a river or in a branch of a river when the water flow ceases. The Billabong word is believed to have derived from the Indigenous Wiradjuri language from south-western New South Wales. The word occurs frequently in Australian folk songs, ballads, poetry and fiction. -

Australian & New Zealand

Australian & New Zealand Art Collectors’ List No. 176, 2015 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke Street) Kensington (Sydney) NSW Ph: (02) 9663 4848 Email: [email protected] Web: joseflebovicgallery.com 1. Ernest E. Abbott (Aust., JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY 1888-1973). The First Sheep Established 1977 Station [Elizabeth Farm], c1930s. Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney) NSW Drypoint, titled, annot ated “Est. by John McArthur [sic], 1793. Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia Final” and signed in pencil in Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 lower mar gin, 18.9 x 28.8cm. Small stain to image lower centre, Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com old mount burn. Open: Mon. to Sat. by appointment or by chance. ABN 15 800 737 094 $770 Member: Aust. Art & Antique Dealers Assoc. • Aust. & New Zealand Assoc. of English-born printmaker, painter and art teacher Abbott migrated to Aus- Antiquarian Booksellers • International Vintage Poster Dealers Assoc. • Assoc. of tralia in 1910, eventually settling in International Photography Art Dealers • International Fine Print Dealers Assoc. Melbourne, Victoria, after teaching art at Stott’s in South Australia. Largely self-taught, he took up drypoint etching, making his own engraving tools. Ref: DAAO. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 176, 2015 2. Anon. Sydney From Kerosene Bay, c1914. Watercolour, titled in pencil lower right, 22.8 x 32.9cm. Foxing, old mount burn. Australian & New Zealand Art $990 Possibly inspired by Henry Lawson’s On exhibition from Wednesday, 1 April to Saturday, 16 May. poem, Kerosene Bay written in 1914: “Tis strange on such a peaceful day / All items will be illustrated on our website from 11 April. -

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA

arts Article Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA Marie Geissler Faculty of Law Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia; [email protected] Received: 19 February 2019; Accepted: 28 April 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: This paper explores how the appeal of the imagery of the Arnhem Land bark painting and its powerful connection to land provided critical, though subtle messaging, during the post-war Australian government’s tourism promotions in the USA. Keywords: Aboriginal art; bark painting; Smithsonian; Baldwin Spencer; Tony Tuckson; Charles Mountford; ANTA To post-war tourist audiences in the USA, the imagery of Australian Aboriginal culture and, within this, the Arnhem Land bark painting was a subtle but persistent current in tourism promotions, which established the identity and destination appeal of Australia. This paper investigates how the Australian Government attempted to increase American tourism in Australia during the post-war period, until the early 1970s, by drawing on the appeal of the Aboriginal art imagery. This is set against a background that explores the political agendas "of the nation, with regards to developing tourism policies and its geopolitical interests with regards to the region, and its alliance with the US. One thread of this paper will review how Aboriginal art was used in Australian tourist designs, which were applied to the items used to market Australia in the US. Another will explore the early history of developing an Aboriginal art industry, which was based on the Arnhem Land bark painting, and this will set a context for understanding the medium and its deep interconnectedness to the land. -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

Download This PDF File

Illustrating Mobility: Networks of Visual Print Culture and the Periodical Contexts of Modern Australian Writing VICTORIA KUTTAINEN James Cook University The history of periodical illustration offers a rich example of the dynamic web of exchange in which local and globally distributed agents operated in partnership and competition. These relationships form the sort of print network Paul Eggert has characterised as being shaped by everyday exigencies and ‘practical workaday’ strategies to secure readerships and markets (19). In focussing on the history of periodical illustration in Australia, this essay seeks to show the operation of these localised and international links with reference to four case studies from the early twentieth century, to argue that illustrations offer significant but overlooked contexts for understanding the production and consumption of Australian texts.1 The illustration of works published in Australia occurred within a busy print culture that connected local readers to modern innovations and technology through transnational networks of literary and artistic mobility in the years also defined by the rise of cultural nationalism. The nationalist Bulletin (1880–1984) benefited from a newly restricted copyright scene, while also relying on imported technology and overseas talent. Despite attempts to extend the illustrated material of the Bulletin, the Lone Hand (1907–1921) could not keep pace with technologically superior productions arriving from overseas. The most graphically impressive modern Australian magazines, the Home (1920–1942) and the BP Magazine (1928–1942), invested significant energy and capital into placing illustrated Australian stories alongside commercial material and travel content in ways that complicate our understanding of the interwar period. One of the workaday practicalities of the global book trade which most influenced local Australian producers and consumers prior to the twentieth century was the lack of protection for international copyright. -

Ii: Mary Alice Evatt, Modern Art and the National Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cultivating the Arts Page 394 CHAPTER 9 - WAGING WAR ON THE ESTABLISHMENT? II: MARY ALICE EVATT, MODERN ART AND THE NATIONAL ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES The basic details concerning Mary Alice Evatt's patronage of modern art have been documented. While she was the first woman appointed as a member of the board of trustees of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, the rest of her story does not immediately suggest continuity between her cultural interests and those of women who displayed neither modernist nor radical inclinations; who, for example, manned charity- style committees in the name of music or the theatre. The wife of the prominent judge and Labor politician, Bert Evatt, Mary Alice studied at the modernist Sydney Crowley-Fizelle and Melbourne Bell-Shore schools during the 1930s. Later, she studied in Paris under Andre Lhote. Her husband shared her interest in art, particularly modern art, and opened the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society in Melbourne 1939, and an exhibition in Sydney in the same year. His brother, Clive Evatt, as the New South Wales Minister for Education, appointed Mary Alice to the Board of Trustees in 1943. As a trustee she played a role in the selection of Dobell's portrait of Joshua Smith for the 1943 Archibald Prize. Two stories thus merge to obscure further analysis of Mary Alice Evatt's contribution to the artistic life of the two cities: the artistic confrontation between modernist and anti- modernist forces; and the political career of her husband, particularly knowledge of his later role as leader of the Labor opposition to Robert Menzies' Liberal Party. -

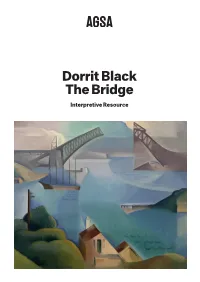

Dorrit Black the Bridge

Dorrit Black The Bridge Interpretive Resource Australian modernist Dorrit Black The Bridge, 1930 was Australia’s first Image (below) and image detail (cover) (1891–1951) was a painter and printmaker cubist landscape, and demonstrated a Dorrit Black, Australia, who completed her formal studies at the new approach to the painting of Sydney 1891–1951, The Bridge, 1930, Sydney, oil on South Australian School of Arts and Crafts Harbour. As the eye moves across the canvas on board, 60.0 x around 1914 and like many of her peers, picture plane, Black cleverly combines 81.0 cm; Bequest of the artist 1951, Art Gallery of travelled to Europe in 1927 to study the the passage of time in a single painting. South Australia, Adelaide. contemporary art scene. During her two The delicately fragmented composition years away her painting style matured as and sensitive colour reveals her French she absorbed ideas of the French cubist cubist teachings including Lhote’s dynamic painters André Lhote and Albert Gleizes. compositional methods and Gleizes’s vivid Black returned to Australia as a passionate colour palette. Having previously learnt to supporter of Cubism and made significant simplify form through her linocut studies contribution to the art community by in London with pioneer printmaker, Claude teaching, promoting and practising Flight, all of Black’s European influences modernism, initially in Sydney, and then in were combined in this modern response to Adelaide in the 1940s. the Australian landscape. Dorrit Black – The Bridge, 1930 Interpretive Resource agsa.sa.gov.au/education 2 Early Years Primary Responding Responding What shapes can you see in this painting? What new buildings have you seen built Which ones are repeated? in recent times? How was the process documented? Did any artists capture The Sydney Harbour Bridge is considered a this process? Consider buildings you see national icon – something we recognise as regularly, which buildings do you think Australian.