DOBELL's CASE (Draft 21 April 2016) Over the Past Couple of Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PORTRAITURE and the PRIZE ART an Education Kit for K–6 Creative Arts with KLA Links GALLERY and 7–12 Visual Arts NSW

PORTRAITURE AND THE PRIZE ART An education kit for K–6 Creative Arts with KLA links GALLERY and 7–12 Visual Arts NSW ARCHIBALD.PRIZE.2010 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Toured by Museums & Galleries New South Wales www.thearchibaldprize.com.au PORTRAITURE AND THE PRIZE Contents General: the Archibald Prize and portraiture Who was JF Archibald? The Archibald Prize 1 A chronology of events Controversy and debate Portraiture as a genre: an overview Portraiture and the Prize: a selection of quotes List of winners since 1921 Syllabus connections: the Archibald Prize and portraiture Suggested case studies Years 7–12 Conceptual framework: the art world web Years 7–12 Framing the Archibald: questions for discussion Years 7–12 2 Portraiture: general strategies Years K–6 Vocabulary: portraiture Artists: portraiture References Syllabus connections: 2010 Archibald Prize Framing the Archibald: K–6 and 7–12 discussion questions and activities Analysing the winner K–6: Visual Arts and links with key learning areas 3 Years 7–12: The frames Focus works: K–6: Visual Arts and links with key learning areas 7–12: Issues for discussion 2010 Archibald Prize: selected artists Education kit outline This education kit has been prepared by the Public Programs Department of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in conjunction with Museums & Galleries New South Wales, to accompany the annual Archibald Prize exhibition. It has been designed to assist primary and secondary students and teachers in their enjoyment and understanding of the Archibald exhibition and the issues surrounding it, at the Art Gallery of NSW or throughout the 2010 Archibald Prize Regional Tour. -

Art Gallery of New South Wales Annual Report 2012 – 13

ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2012 – 13 1 CONTENTS 4 Vision and strategic direction 2010 – 15 5 President’s foreword 9 Director’s statement 13 At a glance 15 Access 15 Exhibitions and audience programs 19 Future exhibitions 21 Publishing 23 Engaging 23 Digital engagement 23 Community 30 Education 35 Outreach Regional NSW 40 Stewarding 40 Building and environmental management 42 Corporate Governance 58 Collecting 58 Major collection acquisitions 67 Other collection activity 70 Appendices 123 General Access Information 131 Financial statements 2 ART GALLERY OF NSW ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 The Hon George Souris MP Minister for Tourism, Major Events, Hospitality and Racing, and Minister for the Arts Parliament House Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister It is our pleasure to forward to you for presentation to the NSW Parliament the annual report for the Art Gallery of NSW for the year ended 30 June 2013. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Report (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulations 2010. Yours sincerely Steven Lowy Michael Brand President Director Art Gallery of NSW Trust 21 October 2013 3 VISION AND STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2010 – 2015 Vision The Gallery is dedicated to serving the widest possible audience, both nationally and internationally, as a centre of excellence for the collection, preservation, documentation, . interpretation and display of Australian and international art. The Gallery is also dedicated to providing a forum for scholarship, art education and the exchange of ideas. Strategic Directions Access To continue to improve access to our collection, resources and expertise through exhibitions, publishing, programs, new technologies and partnerships. -

"Jacky Jacky Was a Smart Young Fella": a Study of Art and Aboriginality in South East Australia 1900-1980 Sylvia Klein

"Jacky Jacky Was a Smart Young Fella": A study of art and Aboriginality in south east Australia 1900-1980 Sylvia Kleinert A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University, April 1994. xiv A note on the title The title of my thesis, "Jacky Jacky Was a Smart Young Fella" is a well-known south eastern Aboriginal song. As in any folk tradition, the origins of the song are obscure and wording varies according to time, place and performer. My title follows the version sung in 1961 by Alick Jackomos, a lifelong supporter of Victorian Aborigines and recorded by Alan West, then a curator at the Museum of Victoria. Some performers, including Percy Mumbulla from the south coast and Alick Jackomos attribute the song to the Wallaga Lake community, others, like the Aboriginal singer, Jimmy Little, and the ethnographer, Anna Vroland, favour Lake Tyers. In 1968 Percy Mumbulla claimed Jacky Jacky was a corroboree song taught to him by Sam Drew (Bubela) however the Lake Tyers informants cited by Vroland attribute the English verses to Captain Newman, manager of Lake Tyers station in 1928- 1931 : they maintain the chorus refers to the arrival of steamer traffic between Bairnsdale and Orbost at the turn of the century. The tune, in all cases, resembles the Liverpool song, "Johnny Todd". The song thus selectively incorporates from Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal traditions. Most particularly, "Jacky Jacky" encapsulates the way that south eastern Aborigines accommodated a colonial presence by parodying, and thereby gaining some control over, existing stereotypes. Through this inversion, humour becomes a tactical weapon in a song of political protest played back to the majority culture. -

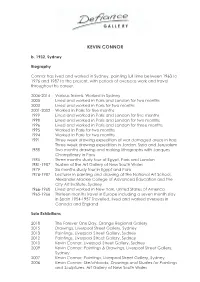

KEVIN CONNOR B

KEVIN CONNOR b. 1932, Sydney Biography Connor has lived and worked in Sydney, painting full time between 1963 to 1976 and 1987 to the present, with periods of overseas work and travel throughout his career. 2006-2014 Various travels. Worked in Sydney 2005 Lived and worked in Paris and London for two months 2003 Lived and worked in Paris for two months 2001-2002 Worked in Paris for five months 1999 Lived and worked in Paris and London for five months 1998 Lived and worked in Paris and London for two months 1996 Lived and worked in Paris and London for three months 1995 Worked in Paris for two months 1994 Worked in Paris for two months 1991 Three week drawing expedition of war damaged areas in Iraq Three week drawing expedition in Jordan, Syria and Jerusalem 1988 Two months drawing and making lithographs with Jacques Champfleury in Paris 1985 Three months study tour of Egypt, Paris and London 1981-1987 Trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales 1979 Six months study tour in Egypt and Paris 1976-1987 Lecturer in painting and drawing at the National Art School, Alexander Mackie College of Advanced Education and the City Art Institute, Sydney 1966-1968 Lived and worked in New York, United States of America 1965-1966 Thirteen months travel in Europe including a seven month stay in Spain 1954-1957 Travelled, lived and worked overseas in Canada and England Solo Exhibitions 2018 The Forever One Day, Orange Regional Gallery 2015 Drawings, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2013 Paintings, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2012 Paintings, Liverpool -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

Chapter 9 of the Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 Which Was Introduced by the Civil Law (Wrongs) Amendment Act 2005 and Commenced on 23 February 2006

PROTECTING REPUTATION DEFAMATION PRACTICE, PROCEDURE AND PRECEDENTS THE MANUAL by Peter Breen Protecting Reputation Defamation Practice, Procedure and Precedents THE MANUAL © Peter Breen 2014 Peter Breen & Associates Solicitors 164/78 William Street East Sydney NSW 2011 Tel: 0419 985 145 Fax: (02) 9331 3122 Email: [email protected] www.defamationsolicitor.com.au Contents Section 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 Section 2 Current developments and recent cases ................................................. 5 Section 3 Relevant legislation and jurisdiction ..................................................... 11 3.1 Uniform Australian defamation laws since 2006 ........................................ 11 3.2 New South Wales law [Defamation Act 2005] ........................................... 11 3.3 Victoria law [Defamation Act 2005] .......................................................... 13 3.4 Queensland law [Defamation Act 2005] ..................................................... 13 3.5 Western Australia law [Defamation Act 2005] .......................................... 13 3.6 South Australia law [Defamation Act 2005] .............................................. 14 3.7 Tasmania law [Defamation Act 2005] ........................................................ 14 3.8 Northern Territory law [Defamation Act 2006] .......................................... 15 3.9 Australian Capital Territory law [Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002] ............. 15 3.10 -

High Court of Australia

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2000-01 High Court of Australia Canberra ACT 7 December 2001 Dear Attorney, In accordance with Section 47 of the High Court of Australia Act 1979, I submit on behalf of the Court and with its approval a report relating to the administration of the affairs of the High Court of Australia under Section 17 of the Act for the year ended 30 June 2001, together with financial statements in respect of the year in the form approved by the Minister for Finance. Sub-section 47(3) of the Act requires you to cause a copy of this report to be laid before each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after its receipt by you. Yours sincerely, (C.M. DOOGAN) Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia The Honourable D. Williams, AM, QC, MP Attorney-General Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 CONTENTS Page PART I - PREAMBLE Aids to Access 4 PART II - INTRODUCTION Chief Justice Gleeson 5 Justice Gaudron 5 Justice McHugh 6 Justice Gummow 6 Justice Kirby 6 Justice Hayne 7 Justice Callinan 7 PART III - THE YEAR IN REVIEW Changes in Proceedings 8 Self Represented Litigants 8 The Court and the Public 8 Developments in Information Technology 8 Links and Visits 8 PART IV - BACKGROUND INFORMATION Establishment 9 Functions and Powers 9 Sittings of the Court 9 Seat of the Court 11 Appointment of Justices of the High Court 12 Composition of the Court 12 Former Chief Justices and Justices of the Court 13 PART V - ADMINISTRATION General 14 External Scrutiny 14 Ecologically Sustainable Development -

Scientists' Houses in Canberra 1950–1970

EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 MILTON CAMERON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cameron, Milton. Title: Experiments in modern living : scientists’ houses in Canberra, 1950 - 1970 / Milton Cameron. ISBN: 9781921862694 (pbk.) 9781921862700 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Scientists--Homes and haunts--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Architecture, Modern Architecture--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Canberra (A.C.T.)--Buildings, structures, etc Dewey Number: 720.99471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Sarah Evans. Front cover photograph of Fenner House by Ben Wrigley, 2012. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press; revised August 2012 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Illustrations . xi Abbreviations . xv Introduction: Domestic Voyeurism . 1 1. Age of the Masters: Establishing a scientific and intellectual community in Canberra, 1946–1968 . 7 2 . Paradigm Shift: Boyd and the Fenner House . 43 3 . Promoting the New Paradigm: Seidler and the Zwar House . 77 4 . Form Follows Formula: Grounds, Boyd and the Philip House . 101 5 . Where Science Meets Art: Bischoff and the Gascoigne House . 131 6 . The Origins of Form: Grounds, Bischoff and the Frankel House . 161 Afterword: Before and After Science . -

Annual Report 2010–11

ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Thapich Gloria Fletcher Dhaynagwidh (Thaynakwith) people The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the Eran 2010 cultural enrichment of all Australians through access aluminium to their national art gallery, the quality of the national 270 cm (diam) collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra programs, and the professionalism of Gallery staff. acquired through the Founding Donors 2010 Fund, 2010 Photograph: John Gollings The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, (back cover) corporate governance, administration and financial and Hans Heysen business management. Morning light 1913 oil on canvas In 2010–11, the National Gallery of Australia received 118.6 x 102 cm an appropriation from the Australian Government National Gallery of Australia, Canberra totalling $50.373 million (including an equity injection purchased with funds from the Ruth Robertson Bequest Fund, 2011 of $15.775 million for development of the national in memory of Edwin Clive and Leila Jeanne Robertson collection and $2 million for the Stage 1 South Entrance and Australian Indigenous Galleries project), raised $27.421 million, and employed 262 full‑time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2011 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Ii: Mary Alice Evatt, Modern Art and the National Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cultivating the Arts Page 394 CHAPTER 9 - WAGING WAR ON THE ESTABLISHMENT? II: MARY ALICE EVATT, MODERN ART AND THE NATIONAL ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES The basic details concerning Mary Alice Evatt's patronage of modern art have been documented. While she was the first woman appointed as a member of the board of trustees of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, the rest of her story does not immediately suggest continuity between her cultural interests and those of women who displayed neither modernist nor radical inclinations; who, for example, manned charity- style committees in the name of music or the theatre. The wife of the prominent judge and Labor politician, Bert Evatt, Mary Alice studied at the modernist Sydney Crowley-Fizelle and Melbourne Bell-Shore schools during the 1930s. Later, she studied in Paris under Andre Lhote. Her husband shared her interest in art, particularly modern art, and opened the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society in Melbourne 1939, and an exhibition in Sydney in the same year. His brother, Clive Evatt, as the New South Wales Minister for Education, appointed Mary Alice to the Board of Trustees in 1943. As a trustee she played a role in the selection of Dobell's portrait of Joshua Smith for the 1943 Archibald Prize. Two stories thus merge to obscure further analysis of Mary Alice Evatt's contribution to the artistic life of the two cities: the artistic confrontation between modernist and anti- modernist forces; and the political career of her husband, particularly knowledge of his later role as leader of the Labor opposition to Robert Menzies' Liberal Party. -

KEVIN CONNOR B

KEVIN CONNOR b. 1932, Sydney BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES Connor has lived and worked in Sydney, painting full time between 1963 to 1976 and 1987 to the present, with periods of overseas work and travel throughout his career. 2006-2014 Various travels. Worked in Sydney 2005 Lived and worked in Paris and London for two months 2003 Lived and worked in Paris for two months 2001-2002 Worked in Paris for five months 1999 Lived and worked in Paris and London for five months 1998 Lived and worked in Paris and London for two months 1996 Lived and worked in Paris and London for three months 1995 Worked in Paris for two months 1994 Worked in Paris for two months 1991 Three week drawing expedition of war damaged areas in Iraq Three week drawing expedition in Jordan, Syria and Jerusalem 1988 Two months drawing and making lithographs with Jacques Champfleury in Paris 1985 Three months study tour of Egypt, Paris and London 1981-1987 Trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales 1979 Six months study tour in Egypt and Paris 1976-1987 Lecturer in painting and drawing at the National Art School, Alexander Mackie College of Advanced Education and the City Art Institute, Sydney 1966-1968 Lived and worked in New York, United States of America 1965-1966 Thirteen months travel in Europe including a seven month stay in Spain 1954-1957 Travelled, lived and worked overseas in Canada and England SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Drawings, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2013 Paintings, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2012 Paintings, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2010 Kevin Connor, -

The Devil's Triangle

THE DEVIL’S TRIANGLE Civil liberties and the relationship between the law, the media and the parliament Bob Debus Attorney General of New South Wales 2000-2007 Sir Frank Kitto Lecture, University of New England, November 23rd 2012. This Lecture commemorates the great figure in Australian legal history Justice Sir Frank Kitto, who served on The High Court of Australia from 1950 to 1970 and was thereupon elected Chancellor of this University. As long ago as 1998 Justice Michael Kirby used this lecture to describe not only Sir Frank’s contribution to the law but his high integrity, demonstrated for instance, in the unequivocal judgment in which he joined the majority in Communist the seminal decision to strike down the Menzies Government’s Party Dissolution Act 1950. It was the beginning of the Cold War but Kitto was immune to the politics of the situation: “…it may have been thought (although never said in those more graceful days) that Justice Kitto was a ‘capital C conservative’. His skills were in the black letter law… He had just succeeded in a substantial brief for the banks in striking down the nationalisation scheme of the former Labor Government. Yet in less than a year, he performed his function as a judge of our highest court, in accordance with his understanding of the law and the Constitution precisely and only as his learning and 1 conscience dictated.” In the period 1976 to 1982 he was inaugural Chairman of The Australian Press Council. I venture to believe that he may have grudgingly approved the national defamation law finally achieved by the Commonwealth and State Attorneys General in 2005 after years of difficult negotiation.