Download PDF 432.63 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: the Ih Story and the Legend Booth Library

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Booth Library Programs Conferences, Events and Exhibits Spring 2015 Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend Booth Library Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Booth Library, "Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker: The iH story and the Legend" (2015). Booth Library Programs. 15. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/booth_library_programs/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Events and Exhibits at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Booth Library Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quanah & Cynthia Ann Parker: The History and the Legend e story of Quanah and Cynthia Ann Parker is one of love and hate, freedom and captivity, joy and sorrow. And it began with a typical colonial family’s quest for a better life. Like many early American settlers, Elder John Parker, a Revolutionary War veteran and Baptist minister, constantly felt the pull to blaze the trail into the West, spreading the word of God along the way. He led his family of 13 children and their descendants to Virginia, Georgia and Tennessee before coming to Illinois, where they were among the rst white settlers of what is now Coles County, arriving in c. 1824. e Parkers were inuential in colonizing the region, building the rst mill, forming churches and organizing government. One of Elder John’s many grandchildren was Cynthia Ann Parker, who was born c. -

Carmel Pine Cone, February 8, 2013 (Main News)

PEBBLE BEACH NATIONAL PRO-AM 2013 A SPECIAL ATSECTION INSIDE &TODAYS CARMELT PINE CONE — The pros and celebrities schedules, ticket info, how to get there & more… Volume 99 No. 6 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com February 8-14, 2013 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 Super Bowl coach is last-minute add to Pro-Am Hardy: Vesuvio By MARY SCHLEY tequila party HIS TEAM didn’t win the Super Bowl, but head coach Jim ‘disgusting’ Harbaugh was able to console himself at least a little by joining the field of this week’s AT&T and ‘appalling’ Pebble Beach National Pro-Am, one of the most popular and suc- n Pepe: Take it back or I’ll sue cessful tournaments on the PGA Tour. By MARY SCHLEY “He played last year, and he’s a friend of the tournament, and A CARMEL resident who wants the town to be quiet obviously, he’s a major draw,” and a restaurateur who wants it to have a bit more nightlife Monterey Peninsula Foundation are battling over plans for a racy party in the rooftop bar at a CEO Steve John, who oversees the downtown restaurant. tournament, said Thursday from At Tuesday’s council meeting, Carolyn Hardy asked the the 1st Tee at the Monterey council to protect her First Amendment right to free speech Peninsula Country Club Shore about what she feels is best for the town, but city attorney Course as celebrities and top pros PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES Don Freeman advised the mayor and council to stay out of a started their first round of com- San Francisco 49ers coach Jim Harbaugh made quite a fashion statement with some local fight that could end up in court. -

Cynthia Ann Parker, the White Indian Princess Robin Montgomery

Volume 1 Article 13 Issue 2 Winter 12-15-1981 Cynthia Ann Parker, The White Indian Princess Robin Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/westview Recommended Citation Montgomery, Robin (1981) "Cynthia Ann Parker, The White Indian Princess," Westview: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/westview/vol1/iss2/13 This Nonfiction is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Westview by an authorized administrator of SWOSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANS CYNTHIA ANN PARKER, THE WHITE INDIAN PRINCESS - Robin Montgomery On May 19, 1836, several hundred Comanche and Kiowa Indians attacked Fort Parker. During the next half hour in what is now Limestone County, Texas, the frenzied warriors broke inside the gates of the fort and nearly decimated the extended Parker family. Herein was the framework upon which developed one of the most heart-rending dramas in American History; a drama destined to delay until 1875 the closing of the Indian Wars in Texas. This massacre proved to be the breeding ground for the saga of Cynthia Ann Parker. As a nine-year-old girl, amidst the groans of her dying relatives and the blood-curdling screams of the Indians, Cynthia Ann was lifted upon a pony and carried away to become the white princess of the Comanches. She lived with these Indians for twenty-four years and seven months during which time she married the Great War Chief, Peta Nocona. -

Untitled Manuscript, Privately Owned, Ca

The Centennial Series of the Association of Former Students, Texas A&M University Frontier The Saga of the Parker Family Blood Jo Ella Powell Exley Copyright © by Jo Ella Powell Exley Manufactured in the United States of America All rights reserved First edition The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, .-. Binding materials have been chosen for durability. -- Exley, Jo Ella Powell, – Frontier blood : the saga of the Parker family / Jo Ella Powell Exley.—st ed. p. cm.—(The centennial series of the Association of Former Students, Texas A&M University ; no. ) Includes bibliographical references and index. --- (alk. paper) . Pioneers—Texas—Biography. Parker family. Frontier and pioneer life—Texas. Parker, Cynthia Ann, ?‒. Parker, Quanah, ?–. Comanche Indians—Texas— History—th century. Indian captivities—Texas. Texas— History—th century—Biography. Pioneers—Southern States—Biography. Frontier and pioneer life—Southern States. I. Title. II. Series. .'' To Jim & Emily, my ever-faithful helpers CONTENTS List of Illustrations Preface . . A Poor Sinner . The Wrong Road . Plain and Unpolished—The Diamond in the Rough State . . Father, Forgive Them . Vengeance Is Mine . How Checkered Are the Ways of Providence . . The Tongue of Slander . The House of God . Sundry Charges . Called Home . . Miss Parker . The Hand of Savage Invasion . The Long-Lost Relative . . Thirsting for Glory . It Was Quanah . So Many Soldiers . Blood upon the Land . I Lived Free Notes Bibliography Index ILLUSTRATIONS Replica of Fort Parker page Sam Houston Lawrence Sullivan Ross Isaac Parker Cynthia Ann Parker and Prairie Flower Cynthia Ann Parker Mowway, Comanche chief Ranald Slidell Mackenzie Mowway’s village in – Isatai, Quahada medicine man Quanah Parker in his war regalia Quanah Parker and Andrew Jackson Houston Genealogy . -

August, 1949 TABLE of CONTENTS

/4Oli TEE HISTORY OF IARIEMAN COUNTY, TEXAS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By J. Paul Jones, B. S. Quanah, Texas August, 1949 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page . V LIST OF TABLES . v Chapter I. THE BACKGROUND AND EARLY HISTORY, 1835-1860 . Creation of Red River Municipality Creation of Fannin County Creation and Naming of Hardeman County Physiographical Description Early Indians of the County Recapture of Cynthia Ann Parker II. FIRST PERIOD OF EXPANSION, 1860-1890 . 26 Last Indian Raid and Indian Remains in the County County Organized The Founding of Towns: Chillicothe, Quanah, and Others Old Trails and Roads Railroads and Railway Passenger Service . 57 Spread of the Cattle Industry III. AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT, 1890-1918 . - - - . 69 Removal of County Seat Separation of Foard County from Hardeman, 1891 Disastrous Flood and Fire of 1891 Beginning of Wheat Farming Expansion of Cotton over the County Demsite Irrigation Project Attempted Agricultural Experiment Station Built Extension and Improvement of Railways IV. GROWTH OF COUNTY FROM 1918 TO 199 . 88 Improvement of Highways Mechanization of Farms iii Chapter page Construction of a Power Plant Development of Quanah Airport V. CULTURAL PROGRESSR,.*... ... .... .105 Newspapers of the County Public School Development Clubs and Organizations Founded CONCLUSION . 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 125 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. late on Cotton in Hardeman County, 1899-1947 . 78 V CHAPTER I TEE BACKGROUND AND EARLY HISTORY, 1835-1860 Creation of Red River Municipality Hardeman County as a political subdivision did not ex- ist until it was created as such by the Texas legislature on February 21, 1858. -

The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1977 The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Joseph Norman Heard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Heard, Joseph Norman, "The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries." (1977). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3157. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3157 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

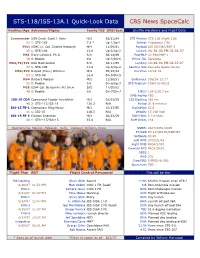

STS-118/ISS-13A.1 Quick-Look Data CBS News Spacecalc

STS-118/ISS-13A.1 Quick-Look Data CBS News SpaceCalc Position/Age Astronaut/Flights Family/TIS DOB/Seat Shuttle Hardware and Flight Data Commander USN Cmdr. Scott J. Kelly M/2 02/21/64 STS Mission STS-118 (flight 119) 43 1: STS-103 7.9 * Up-1/Up-1 Orbiter Endeavour (19) Pilot USMC Lt. Col. Charles Hobaugh M/4 11/05/61 Payload ISS S5/CMG/ESP-3 45 1: STS-104 12.8 Up-2/Up-2 Launch 06:36:36 PM 08.08.07 MS1 Tracy Caldwell, Ph.D. S/0 08/14/69 Pad/MLP LC-39A/MLP-1 38 0: Rookie 0.0 Up-3/Dn-6 Prime TAL Zaragoza MS2/FE/EV1 Rick Mastracchio S/0 02/11/60 Landing 12:49:00 PM 08.22.07 47 1: STS-106 11.8 Up-4/Up-4 Landing Site Kennedy Space Center MS3/EV2 Dafydd (Dave) Williams M/2 05/16/54 Duration 13/18:12 53 1: STS-90 16.0 Dn-5/Dn-5 MS4 Barbara Morgan M/2 11/28/51 Endeavour 206/14:12:17 55 0: Rookie 0.0 Dn-6/Up-3 STS Program 1096/16:48:21 MS5 USAF Col. Benjamin (Al) Drew S/0 11/05/62 48 0: Rookie 0.0 Dn-7/Dn-7 MECO 134.8/35.7 sm OMS Ha/Hp TBD ISS-15 CDR Cosmonaut Fyodor Yurchikhin M/2 01/03/59 ISS Docking 220 sm 48 2: STS-112,ISS-15 129.3 N/A Period 91.6 minutes ISS-15 FE-1 Cosmonaut Oleg Kotov M/2 10/27/65 Inclination 51.6 41 1: ISS-15 118.3 N/A Velocity 17,188 mph ISS-15 FE-2 Clayton Anderson M/2 02/23/59 EOM Miles 5.7 million 48 1: STS-117/ISS-15 55.8 N/A EOM Orbits 218 Mastrachchio, Morgan, Hobaugh, Kelly, Caldwell, Williams, Drew SSMEs 2047/2051/2045 ET/SRB ET-117/Bi130/RSRM97 Software OI-30 Left OMS LP03/31/F1 Right OMS RP04/27/F1 Forward RCS FRC5/20/F1 OBSS 1 RMS 201 Cryo/GN2 5 PRSD/6 GN2 Spacesuits TBD Flight Plan EDT Flight Control Personnel This will be the… ISS Docking Steve Stich Ascent 119th Shuttle mission since STS-1 8/10/07 01:51 PM Matt Abbott Orbit 1 FD (lead) 6th Post-Columbia mission EVA-1 Richard Jones Orbit 2 FD 94th Post-Challenger mission 8/11/07 01:07 PM Mike Moses Planning 20th Flight of Endeavour EVA-2 Steve Stich Entry 90th Day launch 8/13/07 12:07 PM K. -

Rachel Plummer Narrative; a Stirring Narrative Of

HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY R01251 28564 Houston * JM:!l£ libXatf * Texas Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/rachelplummernarOOpark 5*jiHiiiiiiiiiciiiiiimimHiiiiiiiiminiiiiiiiiiiiiHiiiiiimmt]iiiiiiiiiiii[]i iiiiiiE]iiiiiiiiiiiiE3iiimiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiic]iiiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiifiEU> -The- Rachel Plummer Narrative A stirring narrative of adven- ture, hardship and privation in the early days of Texas, depicting struggles with the Indians and other adventures. > ca!iiiiitifiiiC3ii!iiiiiiiiic3iiiiiiiHiiiC2iifiiiiiiiiicaiiiiiieiiiticaiiiiiiiiiiifC2iiiiiiiiitiic3fifiiiifiiiicaiiiiiiiiiiiicaiiiiiiiiiincaiitiiifuiimfiiitiirnnc<* HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY HOUSTON, TEXAS &&.£>. /, JSax 31, Palestine. Oexas. KOlSSl 2*54,4 .. The .. Rachel Plummer Narrative f^fe ^o^Jks^, icLvvu^i i//, u-t <?7 A stirring narrative of adven- ture, hardship and privation in the early days of Texas, depicting struggles with the Indians and other \ adventures,. Copyright, 1926, by Rachel Lofton, Susie Hendrix and Jane Kennedy. 133609 Picture of Quanna Parker, Chief of Comanche Indians, now deceased. N r Please do n &is book or turn down the p; Forewon In presenting this little book to the public, our aim and desire is to impress or refresh the minds of the people of the hardships and suffering the pioneer settlers of Texas had to endure in opening the way for the blessings and civilization the people of Texas now enjoy. We realize the fact, that half has never yet been told, no doubt it never will all be told. Our grandfather has only given a brief sketch of his travels and trials while seeking to rescue his daughter and grandson from captivity by the Redmen; also his niece, Cyntha Ann Parker, that was captured at the Parker Fort massacre on the Navasota River ; and it is not our desire to rekindle the ill feelings between the Redmen and the Paleface men, that existed between the two tribes at that time. -

Curator's Corner

The BOOKMARK A publication of the Foundation for Lincoln City Libraries BROWSE AT YOUR OWN RISK! It’s time for the annual Lincoln City Libraries’ Book Sale. We hope to see you, your family, relatives, and neighbors for another terrific Book Sale. The volunteers have been sorting for the last year to ensure that thousands of quality books are available for new homes. We hope that you can’t resist the temptation to buy that book you never realized you needed (or even existed). There is something for everyone and all ages! Please join us at the Lancaster Event Center 4100 N. 84th Street at the following times: Thursday October 27, 10 a.m. – 7 p.m. Friday October 28, 10 a.m. – 7 p.m. Saturday October 29, 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. Sunday, October 30, 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. UNL’s student Rotary Group, Rotaract, spent their afternoon helping at the 2015 Book Sale. PREVIEW SALE: If you want to get an early start, please join us at the Preview Sale: Wednesday October 26, 4:30 p.m.-8:30 p.m. This is a fundraiser to benefit Lincoln City Libraries. Tickets are $40, and for Friends of Lincoln City Libraries’ members $35. On October 1, tickets are $50. Your ticket will also provide you with a sandwich, chips, and a beverage to enjoy as you are search through over 100,000 books! VOLUNTEERS NEEDED! Volunteers from B & R Stores joined the fun at the 2015 Book Sale, Volunteers are needed throughout the book sale! If you have an hour or two, the entire week, or belong to a group looking for a project, we invite you to join the fun! Lincoln’s own Jimmy Buffet fan club, the Corn Republic Parrot Head Club, is adding to the fun as their members are once again volunteering! They truly live up to their motto, “Party with a purpose in an effort to make our community just a little better than we found it.” To volunteer or if you have questions, call Gail McNair at 402-441-0164; E-mail – [email protected]; or visit the website, www.foundationforlcl.org. -

Spring 2020 Commencement Program Book

Spring 2020 Fayetteville, Arkansas Contents: Commencement Program – 3 The Academic Procession – 4 The Official Party – 5 Notes on Ceremony – 6 Honorary Degree Recipient – 7 Degree Candidates – 8 Senior Scholars – 25 Past Honorary Degree Recipients – 82 Board of Trustees – 84 Colleges: Graduate School – 3 School of Law – 21 Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences – 27 Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design – 36 J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences – 38 College of Education and Health Professions – 50 College of Engineering – 57 Sam M. Walton College of Business – 68 2 GRADUATE SCHOOL SPRING 2020 2 THE ACADEMIC PROCESSION Chief Marshal and Bearer of the Mace Candidates for Specialist Degrees The Official Party Candidates for Master’s Degrees Faculty of the University Candidates for Juris Doctor Degrees Candidates for Doctoral Degrees Candidates for Baccalaureate Degrees Chief Marshal and Bearer of the Mace Stephen Caldwell, Chair of the Campus Faculty Associate Professor, Music Marshals Adnan A. K. Alrubaye, Research Assistant Douglas D. Rhoads, University Professor, Professor, Biological Sciences Biological Sciences and Poultry Science Barbara B. Shadden, University Professor Emerita, Valerie H. Hunt, Associate Professor, Rehabilitation, Human Resources and Political Science Communication Disorders Charles Leflar,Clinical Professor, Kate Shoulders, Associate Professor, Accounting Agricultural Education, Communication and Harry Pierson, Assistant Professor, Technology Industrial Engineering Anna Zajicek, Professor, Sociology and Criminology Banner Carriers Nancy Arnold, Director of Credit Studies, John M. Norwood, Professor, Global Campus Accounting Kristopher R. Brye, Professor, Graduate School and Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences International Education Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Gary Prinz, Associate Professor, Life Sciences Civil Engineering Alphonso W. -

Representations of Texas Indians in Texas Myth and Memory: 1869-1936

REPRESENTATIONS OF TEXAS INDIANS IN TEXAS MYTH AND MEMORY: 1869-1936 A Dissertation by TYLER L. THOMPSON Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Angela Hudson Committee Members, Walter Buenger Carlos Blanton Cynthia Bouton Joseph Jewell Head of Department, David Vaught August 2019 Major Subject: History Copyright 2019 Tyler Leroy Thompson ABSTRACT My dissertation illuminates three important issues central to the field of Texas Indian history. First, it examines how Anglo Texans used the memories of a Texas frontier with “savage” Indians to reinforce a collective identity. Second, it highlights several instances that reflected attempts by Anglo Texans to solidify their place as rightful owners of the physical land as well as the history of the region. Third, this dissertation traces the change over time regarding these myths and memories in Texas. This is an important area of research for several reasons. Texas Indian historiography often ends in the 1870s, neglecting how Texas Indians abounded in popular literature, memorials, and historical representations in the years after their physical removal. I explain how Anglo Texans used the rhetoric of race and gender to “other” indigenous people, while also claiming them as central to Texas history and memory. Throughout this dissertation, I utilize primary sources such as state almanacs, monument dedication speeches, newspaper accounts, performative acts, interviews, and congressional hearings. By investigating these primary sources, my goal is to examine how Anglo Texans used these representations in the process of dispossession, collective remembrance, and justification of conquest, 1869-1936. -

From Hate Crimes to Activism: Race, Sexuality, and Gender in the Texas Anti-Violence Movement

FROM HATE CRIMES TO ACTIVISM: RACE, SEXUALITY, AND GENDER IN THE TEXAS ANTI-VIOLENCE MOVEMENT _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Christopher P. Haight May 2016 FROM HATE CRIMES TO ACTIVISM: RACE, SEXUALITY, AND GENDER IN THE TEXAS ANTI-VIOLENCE MOVEMENT _________________________ Christopher P. Haight APPROVED: _________________________ Nancy Beck Young, Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________ Linda Reed, Ph.D. _________________________ Eric H. Walther, Ph.D. _________________________ Leandra Zarnow, Ph.D. _________________________ Maria C. Gonzalez, Ph.D. University of Houston _________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics ii FROM HATE CRIMES TO ACTIVISM: RACE, SEXUALITY, AND GENDER IN THE TEXAS ANTI-VIOLENCE MOVEMENT _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Christopher P. Haight May 2016 ABSTRACT This study combines the methodologies of political and grassroots social history to explain the unique set of conditions that led to the passage of the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act in Texas. In 2001, the socially conservative Texas Legislature passed and equally conservative Republican Governor Rick Perry signed the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act, which added race, color, religion, national origin, and “sexual preference” as protected categories under state hate crime law. While it appeared that this law was in direct response to the nationally and internationally high-profile hate killing of James Byrd, Jr.