Autism, Parallel Embodiment, and Elemental Empathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Anxiety, Stress & Effective Living on the Autism Spectrum

Anxiety, Stress & Effective Living on the Autism Spectrum -Ava Ruth Baker Session Outline • What are stress & anxiety? • Fight / flight response • Executive function issues, stress & AS • Management & Prevention (emphasis on self-help) – General principles & range of options – Strategies for calming – Mind / Body approaches – Exposure anxiety – Cognitive Therapy • Concluding ideas: Beyond ‘tools’ • Further reading & references Terminology ‘Autistic’ / ‘autism’ / ‘AS’ (autism spectrum) = (person) anywhere on autism spectrum including Asperger’s, PDD etc ‘NT’ (neurotypical) / ‘NS’ (non-spectrum) = (person) not on autism spectrum What are stress & anxiety? • Anxiety: ‘a condition of excessive uneasiness or agitation’ • Stress: a condition of strain ‘when the demands imposed on you from the outside world outweigh your ability to cope with those demands’ (1) become strained, overwhelmed, anxious (1)Evans et al 2005; Gregson & Looker 1997 What are stress & anxiety? • Universal human experience: healthy & necessary • Part of body’s fight / flight response (stress response) • needed to activate us to • respond to threats • be focused, efficient, perform at our best • be motivated & ‘inspired’ • This activated state can be experienced as either • positive when excited, inspired, mastering challenges - or • negative when pressured, anxious, overwhelmed by challenges Autonomic nervous system • Involuntary: runs automatically (mostly subconsciously) • two opposing parts: – Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) =‘accelerator’ mobilizes for fight / flight, -

Gesnerus 2020-2.Indb

Gesnerus 77/2 (2020) 279–311, DOI: 10.24894/Gesn-de.2020.77012 Vom «autistischen Psychopathen» zum Autismusspektrum. Verhaltensdiagnostik und Persönlichkeitsbehauptung in der Geschichte des Autismus Rüdiger Graf Abstract Der Aufsatz untersucht das Verhältnis von Persönlichkeit und Verhalten in der Defi nition und Diagnostik des Autismus von Kanner und Asperger in den 1940er Jahren bis in die neueren Ausgaben des DSM und ICD. Dazu unter- scheidet er drei verschiedene epistemische Zugänge zum Autismus: ein exter- nes Wissen der dritten Person, das über Verhaltensbeobachtungen, Testver- fahren und Elterninterviews gewonnen wird; ein stärker praktisches Wissen der zweiten Person, das in der andauernden, alltäglichen Interaktion bei El- tern und Betreuer*innen entsteht, und schließlich das introspektive Wissen der ersten Person, d.h. der Autist*innen selbst. Dabei resultiert die Kerndif- ferenz in der Behandlung des Autismus daraus, ob man meint, die Persönlich- keit eines Menschen allein über die Beobachtung von Verhaltensweisen er- schließen zu können oder ob es sich um eine vorgängige Struktur handelt, die introspektiv zugänglich ist, Verhalten prägt und ihm Sinn verleihen kann. Die Entscheidung hierüber führt zu grundlegend anderen Positionierungen zu verhaltenstherapeutischen Ansätzen, wie insbesondere zu Ole Ivar Lovaas’ Applied Behavior Analysis. Autismus; Psychiatriegeschichte; Wissensgeschichte; Verhaltenstherapie; Neurodiversität PD Dr. Rüdiger Graf, Leibniz-Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam, Am Neuen Markt 1, 14467 Potsdam, [email protected]. Gesnerus 77 (2020) 279 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 01:45:02AM via free access «Autistic Psychopaths» and the Autism Spectrum. Diagnosing Behavior and Claiming Personhood in the History of Autism The article examines how understandings of personality and behavior have interacted in the defi nition and diagnostics of autism from Kanner and As- perger in the 1940s to the latest editions of DSM and ICD. -

AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn

Delft University of Technology AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn van Grunsven, Janna; Roeser, Sabine DOI 10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 Publication date 2021 Document Version Final published version Published in Social Epistemology Citation (APA) van Grunsven, J., & Roeser, S. (2021). AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn. Social Epistemology. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Social Epistemology A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsep20 AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn Janna van Grunsven & Sabine Roeser To cite this article: Janna van Grunsven & Sabine Roeser (2021): AAC Technology, Autism, and the Empathic Turn, Social Epistemology, DOI: 10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2021.1897189 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. -

On the Mystery of Human Consciousness

On the mystery of human consciousness Egon Gál 23 August 2007 Philosophers and natural scientists regularly dismiss consciousness as irrelevant. However, even its critics agree that consciousness is less a problem than a mystery. One way into the mystery is through an understanding of autism. It started with a letter from Michaela Martinková: Dear Egon Gál, Our eldest son, aged almost eight, has Asperger’s Syndrome (AS). It is a diagnosis that falls into the autistic spectrum, but his IQ is very much above average. In an effort to find out how he thinks, I decided that I must find out how we think, and so I read into the cognitive sciences and epistemology. I found what I needed there, although I have an intense feeling that precisely the way of thinking of such people as our son is missing from the mosaic of these sciences. And I think that this missing piece could rearrange the whole mosaic. In the book Philosophy and the Cognitive Sciences, [1] you write, among other things: “Actually the only handicap so far observed in these children (with autism and AS) is that they cannot use human psychology. They cannot postulate intentional states in their own minds and in the minds of other people.” I think that deeper knowledge of autism, and especially of Asperger’s Syndrome as its version found in people with higher IQ in the framework of autism, could be immensely enriching for the cognitive sciences. I am convinced that these people think in an entirely different way from us. [2] Why the present interest in autism? It is generally known that some people whose diagnosis falls under Asperger’s Syndrome, namely people with Asperger’s Syndrome and high-functional autism, show a remarkable combination of highly above-average intelligence and well below-average social ability. -

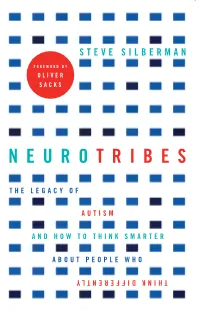

Neuro Tribes

NEURO SMARTER ABOUT PEOPLE WHO THE LEGACY OF ‘NeuroTribes is a sweeping and penetrating history, presented with a rare sympathy and sensitivity . it will change how you think of autism.’—From the foreword by Oliver Sacks STEVE SILBERMAN What is autism: a devastating developmental disorder, a lifelong FOREWORD BY disability, or a naturally occurring form of cognitive difference akin AUTISM to certain forms of genius? In truth, it is all of these things and more OLIVER —and the future of our society depends on our understanding it. TRIBES SACKS Following on from his ground breaking article ‘The Geek Syndrome’, AND HOW TO THINK Wired reporter Steve Silberman unearths the secret history of autism, THINK DIFFERENTLY long suppressed by the same clinicians who became famous for identifying it, and discovers why the number of diagnoses has soared in recent years. Going back to the earliest autism research and chronicling the brave and lonely journey of autistic people and their families through the decades, Silberman provides long-sought solutions to the autism puzzle, while mapping out a path towards a more humane world in which people with learning differences have access to the resources they need to live happier and more meaningful lives. NEUROTRIBES He reveals the untold story of Hans Asperger, whose ‘little professors’ STEVE SILBERMAN were targeted by the darkest social-engineering experiment in human history; exposes the covert campaign by child psychiatrist Leo Kanner THE LEGACY OF to suppress knowledge of the autism spectrum for fifty years; and casts light on the growing movement of ‘neurodiversity’ activists seeking respect, accommodations in the workplace and education, and the right to self-determination for those with cognitive differences. -

REALTIME FILE Drexel the 8Th Annual Autism

REALTIME FILE Drexel The 8th Annual Autism Public Health Lecture Tuesday, December 1, 2020 11:00 AM CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: ALTERNATIVE COMMUNICATION SERVICES, LLC WWW.CAPTIONFAMILY.COM COMMUNICATION ACCESS REALTIME TRANSLATION (CART) IS PROVIDED IN ORDER TO FACILITATE COMMUNICATION ACCESSIBILITY. CART CAPTIONING AND THIS REALTIME FILE MAY NOT BE A TOTALLY VERBATIM RECORD OF THE PROCEEDINGS. >>> Hello and welcome to the 8th annual autism public health lecture. I am Diana Robins director of the institute. Today is our first virtual all Tim public health lecture. Although I am sad that we cannot come together in person, the positive outcome is that people are attending who may not have been able to come to campus so I welcome all of you. I also want to thank the outreach corps for organizing this lecture. Formed in 2012, the A.J. Drexel autism institute was the first autism research center to focus on public health science. Our mission is to understand and address the challenges of autism by discovering, developing, and sharing population level -- and community based public health science. Our institute houses three research programs. The modifiable risk factors is program is led I did Dr. Diana Shendle, the early detection and intervention program is led by me and the life course outcomes is led by Dr. Lindsay Shae who leads the analytics sector. We are supported by three corps. The clinical core is led by Dr. Elizabeth Sheridan, the outreach core is led by Dr. Jennifer plumb and finance and administration services are led by Christine Jacko. Currently we have 54 faculty and staff in the institute and we also work with students and trainees from several Drexel schools and colleges. -

L Brown Presentation

Health Equity Learning Series Beyond Service Provision and Disparate Outcomes: Disability Justice Informing Communities of Practice HEALTH EQUITY LEARNING SERIES 2016-17 GRANTEES • Aurora Mental Health Center • Northwest Colorado Health • Bright Futures • Poudre Valley Health System • Central Colorado Area Health Education Foundation (Vida Sana) Center • Pueblo Triple Aim Corporation • Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition • Rural Communities Resource Center • Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy • Southeast Mental Health Services and Research Organization • The Civic Canopy • Cultivando • The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and • Eagle County Health and Human Transgender Community Center of Services Colorado • El Centro AMISTAD • Tri-County Health Network • El Paso County Public Health • Warm Cookies of the Revolution • Hispanic Affairs Project • Western Colorado Area Health Education Center HEALTH EQUITY LEARNING SERIES Lydia X. Z. Brown (they/them) • Activist, writer and speaker • Past President, TASH New England • Chairperson, Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council • Board member, Autism Women’s Network ACCESS NOTE Please use this space as you need or prefer. Sit in chairs or on the floor, pace, lie on the floor, rock, flap, spin, move around, step in and out of the room. CONTENT/TW I will talk about trauma, abuse, violence, and murder of disabled people, as well as forced treatment and institutions, and other acts of violence, including sexual violence. Please feel free to step out of the room at any time if you need to. BEYOND SERVICE -

Becoming Autistic: How Do Late Diagnosed Autistic People

Becoming Autistic: How do Late Diagnosed Autistic People Assigned Female at Birth Understand, Discuss and Create their Gender Identity through the Discourses of Autism? Emily Violet Maddox Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2019 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTERS .................................................................................................................................... -

1 Recommended Books About the Disability Experience Adventures In

Recommended Books About the Disability Experience Adventures in the Mainstream: Coming of Age with Down Syndrome. (2005). Greg Palmer. Like many parents, Greg Palmer worries about his son’s future. But his son Ned’s last year of high school raises concerns and anxieties for him that most parents don’t experience. Ned has Down syndrome; when high school ends for him, school is out forever. The questions loom: What’s next? How will Ned negotiate the world without the structure of school? Will he find a rewarding job in something other than food service? To help him sort out these questions and document his son’s transition from high school to work, Palmer, an award-winning writer and producer of PBS documentaries, keeps a journal that’s the basis of this thoughtful and entertaining book. (Amazon.com) After the Tears: Parents Talk About Raising a Child With a Disability. (1987). Robin Simons. In parenting a child with a disability you face a major choice. You can believe that your child's condition is a death blow to everything you've dreamed and worked toward until now or you can decide that you will continue to lead the life you'd planned - and incorporate your child into it. Parents who choose the latter course find they do a tremendous amount of growing. This is the story of many such parents - parents who have struggled, learned and grown in the years since their children were born. They share their stories with you to give you the benefit of their experiences, to let you know you're not alone, and to offer you encouragement in growing with and loving your child. -

Download Decision

BEFORE THE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS STATE OF CALIFORNIA In the Consolidated Matters of: PARENT ON BEHALF OF STUDENT, OAH CASE NO. 2013080387 v. LAS VIRGENES UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT, LAS VIRGENES UNIFIED SCHOOL OAH CASE NO. 2013071203 DISTRICT, v. PARENTS ON BEHALF OF STUDENT. DECISION Las Virgenes Unified School District (District) filed a Request for Due Process Hearing in OAH Case No. 2013071203 with the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH), State of California, on July 29, 2013, naming Student. Student filed a Request for Due Process Hearing in OAH Case No. 2013080387 with OAH on August 8, 2013, naming District. OAH consolidated the matters on August 16, 2013, and ordered the 45-day timeline for issuance of the decision to be based on the date the complaint was filed in Student‟s case (OAH Case Number 2013080387). OAH continued the consolidated matter for good cause on September 6, 2013. June R. Lehrman, Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), heard this matter on October 28- 31, 2013, and November 4-6, 2013, in Calabasas, California. Jane DuBovy, Attorney at Law, and Carolina Watts, educational advocate, represented Parents and Student (collectively, Student). Student‟s mother (Mother) attended the hearing on all days. Student‟s father (Father) attended the hearing on October 28, November 4, and November 5, 2013. 1 Wesley B. Parsons and Siobhan H. Cullen, Attorneys at Law, appeared on behalf of District. Mary Schillinger, Assistant Superintendent, and Sahar Barsoum, Coordinator of Special Education, attended the hearing on all days. On the last day of hearing, a continuance was granted for the parties to file written closing arguments and the record remained open until November 20, 2013. -

The Open Notebook – Writing Well About Disability

FTawciettbeor ok Search Reported Features Writing Well about Disability October 24, 2017 Rachel Zamzow Huntstock/disabilityimages.com In June, dozens of protesters with disabilities stormed Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s office in response to Medicaid cuts that were part of a proposed repeal of the Affordable Care Act. Headlines and striking images called attention to the many people who were removed forcibly by Capitol Police, some being lifted out of their wheelchairs. But s.e. smith (spelled in lowercase), a disabled journalist and disability-rights activist who lives in Northern California, was frustrated by most of the coverage. Story after story not only had little substance about the cuts, but also failed to quote a single disabled person. Fed up, smith took action. In three 80-hour weeks, smith launched Disabled Writers, a database that connects journalists with sources who have disabilities. Many of the people on the list are also writers whom editors can hire. On the site, you can search profiles of some 150 sources by specific disability, such as cerebral palsy or blindness, or by area of expertise, from public policy to the sciences to medieval history. Resources like smith’s are a response to persistent problems in media coverage of disability-related topics. (The same issues that aggravated smith plagued stories about September protests against the Graham-Cassidy health care bill, another attempt to repeal Obamacare.) The biggest problem: Though disabled people make up the nation’s largest minority group, their voices are often left out of stories about disabilities. That omission is particularly egregious, according to members of that community.