1749 St George Hanover Square Per Cent of Total Westminster Per Cent Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph MOGINIE (1818-1864)

Joseph MOGINIE (1818-1864) London Electoral Register 1850 St George Hanover Square, Westminster No.4826 Joseph Moginie, House, 9 New-street No.4827 Samuel Moginie, House, 19 Brewer-street 1851 Census 9 New Street, Saint George Hanover Square, London Joseph MOGINIE Head 31yrs Gas fitter [widower] b St George Hanover Square, Middlesex Edmund W. EVANS Lodger 40yrs Letter carrier [unmarried] b Hampstead, Middlesex 1851 Census 7 The Terrace, St James Bermondsey, Surrey Ann WATSON Head 30yrs Milliner [widow] b Portsmouth George WATSON Son 8yrs b Southwark, Surrey Emily WATSON Dau 4yrs b Southwark, Surrey Marriage Register St Mary’s in the Parish of Bermondsey, Surrey No.87 Joseph Moginie, full age, widower, gas fitter of Bermondsey, son of Samuel Moginie, watch maker and Annie Watson, full age, widow of Bermondsey, daughter of Robert Edmunds, builder were married 15 Nov 1851 by Banns. Witnesses: William Holdid and Kate Martin. 1861 Census 7 Spa Terrace, Bermondsey, Southwark Joseph MOGINIE Head 43yrs Clerk (Gas Meter Maker) b Pimlico, Middlesex Annie MOGINIE Wife 44yrs b Portsmouth, Hampshire Louisa MOGINIE Dau 15yrs b Pimlico, Middlesex Samuel MOGINIE Son 7yrs b Bermondsey, Surrey Kate MOGINIE Dau 6yrs b St Pancras, Middlesex Sidney MOGINIE Son 4yrs b St Pancras, Middlesex Florence MOGINIE Dau 2yrs b Bermondsey, Surrey Annie WATSON Step-dau 19yrs Drapers assistant [unmarried] b Whitehall, Middlesex George WATSON Step-son 18yrs Clerk (Wholesale Drapers) [unmarried] b Whitehall, Middlesex Jessie WATSON Step-dau 17yrs Drapers assistant [unmarried] -

House, and Poplar Sanitary Districts. the Metropolitan!Asylum the SERVICES

1163 of infants under one year of age and 35 of persons The lowest death-rates during April in the various sanitary aged upwards of sixty years ; the deaths of infants showed districts were 13’3 in Wands worth, 13’4 in Lewisham (ex- a slight increase, while those of elderly persons showed a cluding Penge), 15’3 in Kensington, 15’6 in Plumstead, 16-(}’ further decline from recent weekly numbers. Five inquest in Hampstead, and 16’2 in Hammersmith ; in the other cases and 5 deaths from violence were registered; and 62, sanitary districts the rates ranged upwards to 25’4 in or more than a third, of the deaths occurred in public St. George Southwark, 27-5 in Holborn, 27’7 in Limehouse, institutions. The causes of 6, or 4 per cent., of the deaths 28-6 in Whitechapel, 29-7 in St. George-in-the-East, 29-8 i]2, in the city last week were not certified. City of London, and 34-0 in St. Luke. During the four weeks of April 696 deaths were referred to the principal zymotic diseases in London; of these, 210 resulted from. VITAL STATISTICS OF LONDON DURING APRIL, 1893. whooping-cough, 172 from diphtheria, 125 from measles, 89 IN the table will be found summarised from scarlet fever, 51 from diarrhoea, 30 from different forms. accompanying I " complete statistics relating to sickness and mortality during of fever (including 28 from enteric fever and 2 from ill- April in each of the forty-one sanitary districts of London. defined forms of continued fever), and 19 from small-pox. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES WESTMINSTER SESSIONS of the PEACE: ENROLMENT, REGISTRATION and DEPOSIT WR Page 1 Reference Descript

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 WESTMINSTER SESSIONS OF THE PEACE: ENROLMENT, REGISTRATION AND DEPOSIT WR Reference Description Dates NOTIFICATION OF FOREIGN ALIENS NOTIFICATION OF FOREIGN ALIENS WR/A/001 Copies of notices relating to 103 aliens from the 1798 Jul overseers of the poor for the parish of Saint French/English Anne to the Clerk of the Peace of Westminster, with covering note written by John Dickson. Lists name, address and country of origin of the aliens 53 documents WR/A/002 Copies of notices relating to 126 aliens from the 1798 Sep overseers of the poor for the parish of Saint French/English Anne to the Clerk of the Peace for Westminster, with covering note written by John Dickson. Lists name, address and country of origin of the aliens 66 documents WR/A/003 Return of aliens residing in the parish of Saint 1798 Jun Unfit Clement Danes made by the overseers of the Not available for general access poor, listing 20 aliens with their name, residence, occupation and duration of residence 1 document WR/A/004 Return of aliens residing in the parishes of 1798 Sep Saint Margaret and Saint John made by the overseers of the poor, listing 53 aliens with their name, arrival date, address and housekeeper's name 1 document WR/A/005 Notice from Peter Agar, householder, to the 1798 Jul parish officer for Saint Martin in the Fields, stating that Mr John Christopher Franckton, a German, is now lodging with him at 11 Old Round Court, Strand 1 document WR/A/006 Notice from P. -

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square St George’s Church Grosvenor Chapel July—October 2016: issue 34 Inside this issue The Rector writes 2 Organ Concerts 3 Services at St George’s 4 Services at Grosvenor Chapel 7 Prisons Mission 8 Parish Officers etc 9 Neighbours 10 St Mark’s Church, Lobatse in the Diocese of Botswana Hyde Park Place Estate Charity 11 s the Rector mentions on now parish priest at St Mark’s, Lo- Africa calling 11 page 2, thanks to the batse in southern Botswana and in generous support of need of funds to enable the parish Contacts 12 A members of the St to purchase a piano. Details may be George’s congregation and wider found on page 11. Please be as gen- took place on Maundy Thursday 1882 family, we have recently honoured erous as you can. when all seems to have been less our pledge to raise £5,000 in sup- than amicable between ourselves Churches Together in Westminster port of a Christian Aid Community and our Salvation Army neighbours features twice between these cov- Partnership project in Kenya. Now on Oxford Street. This came to ers. John Plummer provides an up- light earlier in the year when we have an opportunity to give a date on the CTiW Prisons Mission in Churches Together’s Meet the helping hand a little further south which St George’s has played a pio- Neighbours project invited partici- in Botswana. Links between the St neering role. If you would like to pating churches to visit the Sally George’s Vestry and Southern Af- receive further information or ex- Army’s premises at Regent Hall. -

PUBLIC HEALTH Average; While in Fulham, Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, and Whitechapel, St

March 14, 1891.] TEB BRITISH MEDlCAL JOURNAL. 613 Square, St. James Westminster, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, and London City, the birth-rates were considerably below the PUBLIC HEALTH average; while in Fulham, Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, AND Whitechapel, St. George-in-the-East, and Mile-End Old- POOR-LAW MEDICAL SERVICES. Town, where the population contains a large proportion of young married persons, the birth-rates showed an excess. The deaths of persons belonging to London registered THE TRUE DEATTH-RATES OF LONDON SANITARY during the year under notice were 89,694, equal to an annual DISTRICTS DURING 1890. rate of 20.0 per 1,000 of the estimated population; this rate IN tlle accompanying table will be found summarised the vital exceeded that recorded in any year since 1884, since which and mortal statistics of the forty-one sanitary districts of the date, when the rate was 20.4, it had continuously declined to, metropolis, based upon the Registrar-General's returns for the 17.4 in 1889, the lowest rate since the establishment of civil year 1890. The mortality figures in the table relate to the registration in 1837. During the decade just ended, 1881-90, deatlhs of persons actually belonging to the respective sani- the rate of mortality in London averaged only 19.9 per 1,000;. tary districts, anid( are the result of a complete system of dis- in the ten years 1861-70, it was equal to 24.4, and in the fol- tribution of deaths occurring in the public institutions of lowing ten years, 1871-80, to 22.5 per 1,000. -

A Call for Ideas to Make Grosvenor Square a Great London Space

Evolving Grosvenor Square together 1 At their best, London’s Your invitation to dream A quick introduction to our ‘Shaping the Square’ campaign 2 squares are all things to all people: quiet havens from A short history of our oval square the hustle and bustle of The Grosvenor Square story 3 city life; convenient spaces to meet family or friends; Reimagining Grosvenor Square centres for al fresco eating, Setting the scene for change 4 entertainment and art. Many of them, being famous Here's what we have learned landmarks, are global tourist A summary of what our research has revealed 5 attractions, others attract visitors in quieter ways, each 1,000 Londoners thinking `inside the square' A summary of our quantitative opinion survey 6 having their own unique atmospheres. Focused dreaming London without its squares is A summary of our qualitative focus group research 8 unimaginable and Grosvenor A CALL FOR IDEAS TO MAKE GROSVENOR Square, already popular with Welcome to their square of the future A last word from some very creative local school kids 11 SQUARE A GREAT LONDON SPACE those who know it, has the potential to become London’s leading square again. What happens next? Five principles for success and an inspiring platform 12 Come into the square and join the conversation How you can get involved and share your ideas 13 SHAPING THE SQUARE Evolving Grosvenor Square together 2 YOUR INVITATION TO A quick introduction to our ‘Shaping the Square’ campaign Why? of a thousand Londoners, running We're asking thousands Because we want to reimagine interviews with local residents and and rejuvenate this unique space visitors and creating a panel of experts of people who live, work for all who visit it now and in the to focus on their answers to the future. -

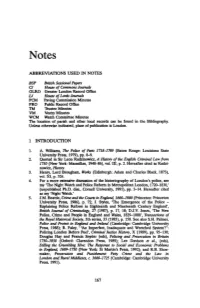

Abbreviations Used in Notes 1 Introduciton 5

Notes ABBREVIATIONS USED IN NOTES BSP British Sessional Papen CJ House of Commons Journals GLRO Greater London Record Office U House of Lords Journals PCM Paving Commission Minutes PRO Public Record Office TM 'Ihlstee Minutes VM Vestry Minutes WCM Watch Committee Minutes The location of parish and other local records can be found in the Bibliography. Unless otheiWise indicated, place of publication is London. 1 INTRODUCITON 1. A Williams, The Police of Paris 1718-1789 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979), pp. 8-9. 2. Quoted in Sir Leon Radzinowicz, A History of the English Criminal Law from 1750 (New York: Macmillan, 1948-86), vol. III, p. 2. Hereafter cited as Radzi nowicz, Hutory. 3. Henry, Lord Brougham, Works (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1873), vol. XI, p. 324. 4. For a more extensive discussion of the historiography of London's police, see my 'The Night Watch and Police Reform in Metropolitan London, 1721J-1830,' (unpublished Ph.D. diss., Cornell University, 1991), pp. 3-14. Hereafter cited as my 'Night Watch.' 5. J.M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England, 1660--1800 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. 72; J. Styles, 'The Emergence of the Police - Explaining Police Reform in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century England', British Journal of Criminology, 27 (1987), p. 17, 18; D.J.V. Jones, 'The New Police, Crime and People in England and Wales, 1829-1888', 'lhmsactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series, 33 (1983), p. 158. See also S.H. Palmer, Police and Protest in England and Irelond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); R. -

COMMERCIAL DIRECTORY, 1895. Sal

1373 COMMERCIAL DIRECTORY, 1895. SAl st. Goorge's (Hanover square)Public Library (Frank Pacy,librarian St. James' Governess School & Domestic Institute (Mrs. CecH & clerk to the commissioners), Buckingham palace road SW Young, sec.), 16gPiccadilly W SL Goorge's (Hanover Square) Workmen's Dwellings Association St. James' Hall Co. Limited (George Wragge, sec.); offices, 28 Picca {R. H. Burden, sec.), 333 Oxford street W dilly W & 73 Regent street W ~ George's East Vestry Office (Horatio Thompson, clerk: George St. James LaundryCo.(HenryThompson,manager),19St.Agnes piS E A. Wilson, surveyor ; Brougham R. Rygate, M. B. medical officer of St. James' & Pall MWl Electric Light Co. Limited (Frederic J. he&l.th; Wm. Chas. Young, analyst; Jas. Geo. Parker, assistant Walker, manager & sec.); offices, Carnaby street, Golden square clerk; JIID!es Wocnton, A.ndrew W. Willey & George Emest W (T A "Licensable"; T N 35o82); .central stations, Carnaby Corill, sanitary inspectors; Alfred Collins, street inspector; H. street, Golden square W & Ma.son's yard, Duke st. St. James' SW Newlyn, messenger), Cable street E St. James' Property Co. Limited, 25 Jermyn street SW St George's German & Engli.eh School, 33 Little Alie street E St. James' Public Baths & Washhouses (William Ross, supt.), 14 St. George's Girls' Friendly Society Lodge and Club (Miss Lucy to 18 Marshal! st W & Dufour's place, ~road st. Golden square W Cotes, secretary), 5 Bourdon street W St. James' Residential Chambers Co. Lim. (Thomas F. Woo<lhouse, m, George's Hall, 4 Langham place, Regent street W sec.), 42 Duke street, St. Ja.mes' SW-TA "Jambers" Bt. -

Monumental Inscriptions in Westminster Graveyards

Westminster City Archives Information Sheet 8 Monumental Inscriptions in Westminster Memorial tablet from St Anne’s, Soho Printed Works for South Westminster General Source Reference Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster. John Stowe, 1720 ff942.11 Lists monuments in churches of St Anne, Archive store St Clement Danes, St James, Piccadilly, St Margaret, St Martin-in-the-Fields, St Mary, Savoy, St Paul, Covent Garden. Christ Church, Broadway List of gravestones. Notes and Queries, Photocopy 22 July 1939 f929.3, pamphlet List of inscriptions on tombstones from the grave- AGR Elliott, Typescript yard on junction of Victoria Street and Broadway, 5 January 1992 f929.3, pamphlet Westminster. City of Westminster Archives Centre 10 St Ann’s Street, London SW1P 2DE Tel: 020-7641 5180, fax: 020-7641 5179 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.westminster.gov.uk/archives January 2010 Westminster City Archives Monumental Inscriptions Information Sheet 8 in Westminster Christ Church, Down Street Source Reference Christ Church, Down Street. Memorial Inscriptions C Tucker, 1971 Typescript 1862-1924. f929.3, pamphlet St Anne, Soho St Anne, Soho, Monumental Inscriptions. AGR Elliott, 1985 Typescript f929.3, pamphlet Monumental Inscriptions and extracts from the WE Hughes, 1905 929.3 registers of births, marriages and deaths at Archive store St Anne’s, Soho. St Clement Danes See entry for John Strype under General St George, Hanover Square Brief History of St George’s Chapel [St George’s Cecil Moore, 1883 942.135 burial ground, Bayswater Road]. Includes Open shelves monumental inscriptions. Mount Street Gardens – Mount Street Burial Ground Westminster City Council, Typescript [St George’s], list of gravestones. -

Poor Law Records in London and Middlesex

RESEARCH GUIDE Poor Law Records in London and Middlesex LMA Research Guide 4: Guide to Poor Law records for London and Middlesex including records held at LMA and other institutions. CONTENTS Introduction Where to find Poor Law Records The Old Poor Law: Parish Records The London Workhouse (CLA/075) London Parishes exempted from the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act The New Poor Law 1834-1930: Boards of Guardians Workhouses Workhouse Infirmaries and Pauper Lunatic Asylums Out Relief Children and Schools Staff Records available online Reading List Introduction Many people in the past have been forced by old age, illness, disability, unemployment, bereavement, or other misfortune to seek assistance from the Poor Law authorities. This assistance might have taken the form of out relief, that is money or food or medical assistance provided while they continued to live in their own homes, or they might have been admitted to the workhouse or treated for illness in the workhouse infirmary or county lunatic asylum. Children may have been brought up and educated in the Poor Law schools and when old enough, apprenticed or placed in service or joined the merchant navy or armed forces. When anyone applied for poor relief, they would probably have undergone a settlement examination to determine which parish was legally responsible for relieving them. The settlement examination would have taken the form of questioning about their life history, including where they were born, whether they had served an apprenticeship or been in service for a year, where they had lived and for how long and what rent they had paid, where their children were born, and even their parents' life histories, as any of these might determine their place of legal settlement or that of their children. -

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square St George’s Church Grosvenor Chapel November 2017 — February 2018: issue 38 Inside this issue The Rector writes 2 Mayfair Organ Concerts 3 Services at St George’s 4 A new Verger 6 Services at Grosvenor Chapel 7 Bishop Edward Holland 8 Prisons Mission 9 Giles Pilgrim Morris 11 St George’s School 13 Handel Messiah 14 HPPEC 15 Contact details 16 terest once wedding couples real- St George’s Undercroft: a new floor is laid. ise they can book a one-stop wed- ding day at St George’s, incorpo- bservant readers of this Yes, work on converting the St rating both the marriage and re- thrice-yearly publication George’s undercroft from a stor- ception? may have noticed that it age area to something integral to Meanwhile life in the Parish con- O varies capriciously in ex- the life of the parish finally began tinues in all its long-established tent between 12 and 16 pages. in August and, all being well, will Indeed on one occasion it even be complete by early next sum- diversity. extended to a massive 20 pages. mer. Meanwhile we are learning St George’s Richards, Fowkes & Co Behind the scenes, Murphy – if how to cope with just one loo and organ is now five years old and he’ll forgive me - ensures that the occasional jack-hammer- this anniversary is marked by a submitted copy inevitably falls induced earth tremors. recital by David Goode on 4th No- somewhere between the magazine vember. editor’s nemesis: the four-page The long-term consequences of multiple. -

First Notice. the Said County of Surry, Victualler

Prisoners in the KI*N G's #E tt C H Prison, \ of the Pariih of St. George in the County of Surry, Pat ternmaker. in the County of Surry. William Wardsworth, late of the PariJh of Christ Church in the County of Surry, now ofthe Pariih of St. Gecrgu in First Notice. the said County of Surry, Victualler. James Cooley, late of the PariJh o'f St. Mary Matfellon, Jonas Dimant, formerly of Kingston upon Thames in the otherwise Whitechapel, Victualler. ' County of Surry, Carpenter and Victualler, late ot" Hamp James Hobbs, formerly of Calne in the County of Wilts, ton Wick in theCounty ofMiddlefex, CA penter. late qf Blackman-street Southwark in the County of Surry, James Scouler the Elder, formerly of Duk"'s Court in the Pa Cordwainer, Haberdasher and Hosier. riJh of St. Martin in the F.elds, late of tht pjr ih of St. Jimes Wilks, formerly of Rebio Hood's Court in the Parisli Ann, both in theCounty of Middlesex, K-rpsichoi-i-makcr. t of St. Mary le Bow, la^e of Little St. Thomas the Apostle, William Holford, formerly of Sunbury, late o; Kr.ighisbr.d^c both in London, Dealer in Cotton. in the County of Middlesex., Merchant. William Vaux, • fortherly of Wboburh in Buckinghamshire, Ezra Waite, formerly of WcT, bank -tt reet, late of Edw H- late of Knightsbridge in the Councy of Middlesex, Spade street, both in the P.uiwi tt St. Mary lo Ben in the: Couniy and Shovel-maker. of Middlesex, Carpenter. Geofge'Spencer the Elder, formerly of the City of Bath in the Robert Woodward, f.rrnerly of Eastcheap, late us SeacoaJ- County of Somerset, Dealer and Chapman, late of Red lane in the PariJh of St.