Alcohol Services in Prisons: an Unmet Need

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nottinghamshire Primary Care Alcohol Misuse Guidelines

Nottinghamshire Primary Care Alcohol Dependence Guidelines V5.2 Last reviewed: April Review date: August 2021 2022 Title Nottinghamshire Primary Care Alcohol Dependence Guidelines Version 5.2 Lead - Dr Stephen Willott, GP Windmill Practice, Nottingham; Clinical Lead for alcohol misuse, Nottingham Recovery Network and Public Health Department, Nottingham City Council Author / Tanya Behrendt, Senior Pharmacist (Nottingham City Locality), NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG Nominated Apollos Clifton-Brown, Operational Manager, Nottingham Recovery Network Dr David Rhinds, Consultant Addictions Psychiatrist, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Lead Dr Kaanthan Jawahar, ST6 Old Age Psychiatry, Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Hannah Godden, Mental Health Interface and Efficiencies Pharmacist, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust/ NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG Jill Theobald, Interface Efficiencies Pharmacist, NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG Approval Date August 2019 Review Date August 2022 Section Contents Page Number i. Summary 2 1. Introduction 4 2. Scope 5 3. Aims of Community Detoxification 5 4. Identifying suitable patients 5 5. Medical risks of community detoxification 6 6. Risk reduction 6 7. Record keeping 7 8. Equipment 7 9. Preparation for home detoxification 7 10. Medication 8 11. Relapse prevention/Follow up 8 12. Reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence 9 13. Potentially difficult situations 10 14. References and version control 10 Appendix A Diagnostic Criteria -

The Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on 4 September 2008 The alcohol withdrawal syndrome A McKeon, M A Frye and Norman Delanty J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008;79;854-862; originally published online 6 Nov 2007; doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.128322 Updated information and services can be found at: http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/79/8/854 These include: References This article cites 115 articles, 38 of which can be accessed free at: http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/79/8/854#BIBL Rapid responses You can respond to this article at: http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/eletter-submit/79/8/854 Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at service the top right corner of the article Notes To order reprints of this article go to: http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform To subscribe to Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry go to: http://journals.bmj.com/subscriptions/ Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on 4 September 2008 Review The alcohol withdrawal syndrome A McKeon,1 M A Frye,2 Norman Delanty1 1 Department of Neurology and ABSTRACT every 26 hospital bed days being attributable to Clinical Neurosciences, The alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a common some degree of alcohol misuse.5 Despite this Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, and management problem in hospital practice for neurologists, Royal College of Surgeons in substantial problem, a survey of NHS general Ireland, Dublin, Ireland; psychiatrists and general physicians alike. Although some hospitals conducted in 2000 and 2003 indicated 2 Department of Psychiatry, patients have mild symptoms and may even be managed that only 12.8% had a dedicated alcohol worker.6 In Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, in the outpatient setting, others have more severe addition, few guidelines exist promoting the USA symptoms or a history of adverse outcomes that requires initiation of clear and uniform AWS treatment 7–9 Correspondence to: close inpatient supervision and benzodiazepine therapy. -

Pharmacological Treatments Protocols of Alcohol and Drugs Abuse

Pharmacological Treatments Protocols of Alcohol and Drugs Abuse 1 Purpose of the protocols: Use and abuse of drugs and alcohol is becoming common and can have serious and harmful consequences on individuals, families, and society. Care with a tailored treatment program and follow-up options can be crucial to success. Treatment should include both medical and mental health services as needed in managing withdrawal symptoms, prevent relapse, and treat co- occurring conditions. Follow-up care may include community- or family-based recovery support systems. These protocols have been developed to guide medical practitioners and nurses in the use of the most effective available treatments of alcohol and drug abuse in the in-patient and out- patient settings and serve as a framework for clinical decisions and supporting best practices. Targeted end users: • Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine Consultants, Specialists and Residents • Nurses • Psychiatry clinical pharmacists • Pharmacists 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Chapter (1) Alcohol 4 3.1 Introduction 4 3.2 Intoxication 4 3.3 Withdrawal 7 2. Chapter (2) Benzodiazepines 21 2.1 Introduction 21 2.2 Intoxication 21 2.3 Withdrawal 22 3. Chapter (3) Opioids 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 Intoxication 28 3.3 Withdrawal 29 4. Chapter (4) Psychostimulants 38 2.1 Introduction 38 2.2 Intoxication 39 2.3 Withdrawal 40 5. Chapter (5) Cannabis 41 3.1 Introduction 41 3.2 Intoxication 41 3.3 Withdrawal 43 6. References 46 3 CHAPTER 1 ALCOHOL INTRODUCTION Alcohol is a Central Nervous System (CNS) depressant. Its’ psychoactive properties contribute to changes in mood, cognition and behavior. -

An Overview of Outpatient and Inpatient Detoxification

An Overview of Outpatient and Inpatient Detoxification Motoi Hayashida, M.D., Sc.D. lcohol detoxification can be defined as a period facility, where they reside for the duration of of medical treatment, usually including counsel- treatment, which may range from 5 to 14 days. A ing, during which a person is helped to overcome The process of detoxification in either setting initially physical and psychological dependence on alcohol (Chang involves the assessment and treatment of acute with- and Kosten 1997). The immediate objectives of alcohol drawal symptoms, which may range from mild (e.g., detoxification are to help the patient achieve a substance- tremor and insomnia) to severe (e.g., autonomic free state, relieve the immediate symptoms of withdrawal, hyperactivity, seizures, and delirium) (Swift 1997). and treat any comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions. Medications often are provided to help reduce a patient’s These objectives help prepare the patient for entry into withdrawal symptoms. Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam long-term treatment or rehabilitation, the ultimate goal of detoxification (Swift 1997). The objectives of long- and chlordiazepoxide) are the most commonly used term treatment or rehabilitation include the long-term drugs for this purpose, and their efficacy is well estab- maintenance of the alcohol-free state and the incor- lished (Swift 1997). Benzodiazepines not only reduce poration of psychological, family, and social interven- alcohol withdrawal symptoms but also prevent alcohol tions to help ensure its persistence (Swift 1997). withdrawal seizures, which occur in an estimated 1 to Alcohol detoxification can be completed safely and 4 percent of withdrawal patients (Schuckit 1995). -

What Works in Alcohol Use Disorders? Jason Luty APT 2006, 12:13-22

What works in alcohol use disorders? Jason Luty APT 2006, 12:13-22. Access the most recent version at DOI: 10.1192/apt.12.1.13 References This article cites 0 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at: http://apt.rcpsych.org/content/12/1/13#BIBL Reprints/ To obtain reprints or permission to reproduce material from this paper, please write permissions to [email protected] You can respond http://apt.rcpsych.org/cgi/eletter-submit/12/1/13 to this article at Downloaded http://apt.rcpsych.org/ on February 18, 2014 from Published by The Royal College of Psychiatrists To subscribe to Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. go to: http://apt.rcpsych.org/site/subscriptions/ Advances in PsychiatricWhat worksTreatment in alcohol (2006), use vol. disorders? 12, 13–22 What works in alcohol use disorders? Jason Luty Abstract Treatment of alcohol use disorders typically involves a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions. About one-quarter of people with alcohol dependence (‘alcoholics’) who seek treatment remain abstinent over 1 year. Research has consistently shown that less intensive, community treatment (particularly brief interventions) is just as effective as intense, residential treatment. Many psychosocial treatments are probably equally effective. Techniques for medically assisted detoxification are widespread and effective. More recent evidence provides some support for the use of drugs such as acamprosate to prevent relapse in the medium to long term. There has been much recent debate and criticism of Unfortunately there are many uncertainties in the UK alcohol policy (Drummond, 2004; Hall, 2005). evidence base for treatment of alcohol use disorders Over the past 20 years, per capita alcohol consump- – not least of which is the cost-effectiveness of tion in Britain has increased by 31%, leading to large therapy. -

Treatment for Cocaine Addiction

(19) TZZ¥_Z_T (11) EP 3 170 499 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 24.05.2017 Bulletin 2017/21 A61K 31/27 (2006.01) A61K 31/16 (2006.01) A61P 25/00 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 16204193.3 (22) Date of filing: 31.08.2011 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB • LEDERMAN, Seth GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO New York, NY 10022 (US) PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR • HARRIS, Herbert New York, NY 10022 (US) (30) Priority: 01.09.2010 US 379095 P (74) Representative: Bassil, Nicholas Charles et al (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in Kilburn & Strode LLP accordance with Art. 76 EPC: 20 Red Lion Street 11832859.0 / 2 611 440 London WC1R 4PJ (GB) (71) Applicant: Tonix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Remarks: New York, NY 10022 (US) This application was filed on 14.12.2016 as a divisional application to the application mentioned under INID code 62. (54) TREATMENT FOR COCAINE ADDICTION (57) A novel pharmaceutical composition is provided therapeutic dose application or a single dose of a com- for the control of stimulant effects, in particular treatment bined therapeutically effective composition of disulfiram of cocaine addiction, or further to treatment of both co- and selegiline compounds or pharmaceutically accepta- caine and alcohol dependency, including simultaneous ble non-toxic salt thereof. EP 3 170 499 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) 1 EP 3 170 499 A1 2 Description and MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), better -

Alcoholic Liver Disease Your Role Is Essential in Preventing, Detecting, and Co-Managing Alcoholic Liver Disease in Inpatient and Ambulatory Settings

Preventing drinking relapse in patients with alcoholic liver disease Your role is essential in preventing, detecting, and co-managing alcoholic liver disease in inpatient and ambulatory settings Gerald Scott Winder, MD lcohol use disorder (AUD) is a mosaic of psychiatric and Assistant Professor medical symptoms. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in its acute Department of Psychiatry University of Michigan Health System and chronic forms is a common clinical consequence of long- Ann Arbor, Michigan A standing AUD. Patients with ALD require specialized care from pro- Jessica Mellinger, MD, MSc fessionals in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. However, Clinical Lecturer medical specialists treating ALD might not regularly consider medi- Department of Internal Medicine University of Michigan Health System cations to treat AUD because of their limited experience with the Ann Arbor, Michigan drugs or the lack of studies in patients with significant liver disease.1 Robert J. Fontana, MD Similarly, psychiatrists might be reticent to prescribe medications for Professor of Medicine AUD, fearing that liver disease will be made worse or that they will Division of Gastroenterology cause other medical complications. As a result, patients with ALD Department of Internal Medicine University of Michigan Health System might not receive care that could help treat their AUD (Box, page 24). Ann Arbor, Michigan Given the high worldwide prevalence and morbidity of ALD,2 gen- Disclosures eral and subspecialized psychiatrists routinely evaluate patients with Dr. Winder and Dr. Mellinger report no financial AUD in and out of the hospital. This article aims to equip a psychia- relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of trist with: competing products. -

3 Regimens for Alcohol Withdrawal and Detoxification

Applied Evidence N EW R ESEARCH F INDINGS T HAT A RE C HANGING C LINICAL P RACTICE 3 Regimens for alcohol withdrawal and detoxification Chad A. Asplund, MD, Jacob W. Aaronson, DO, and Hadassah E. Aaronson, DO Department of Family Practice, DeWitt Army Community Hospital, Fort Belvoir, Va Practice recommendations withdrawal symptoms and no serious psychiatric or medical comorbidities can be safely treated in ■ Patients with mild to moderate alcohol with- the outpatient setting. Patients with history of drawal symptoms and no serious psychi- severe withdrawal symptoms, seizures or deliri- atric or medical comorbidities can be safely um tremens, comorbid serious psychiatric or med- treated in the outpatient setting (SOR: A). ical illnesses, or lack of reliable support network should be considered for detoxification in the ■ Patients with moderate withdrawal should inpatient setting. receive pharmacotherapy to treat their symptoms and reduce their risk of seizures ■ THE PROBLEM OF ALCOHOL and delirium tremens during outpatient WITHDRAWAL detoxification (SOR: A). Up to 71% of individuals presenting for alcohol ■ Benzodiazepines are the treatment of detoxification manifest significant symptoms of choice for alcohol withdrawal (SOR: A). alcohol withdrawal.4 Alcohol withdrawal is a clinical syndrome that affects people accus- ■ ln healthy individuals with mild-to-moderate tomed to regular alcohol intake who either alcohol withdrawal, carbamazepine has decrease their alcohol consumption or stop many advantages making it a first-line drinking completely. treatment for properly selected patients (SOR: A). Physiology Alcohol enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid’s n our small community hospital—with limited (GABA) inhibitory effects on signal-receiving financial and medical resources—we have neurons, thereby lowering neuronal activity, Idesigned and implemented an outpatient alco- leading to an increase in excitatory glutamate hol detoxification clinical practice guideline to pro- receptors. -

Alcohol Detoxification: Inpatient Clinical Algorithm

Alcohol Detoxification: Inpatient Clinical Algorithm CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2. OVERVIEW OF THE PROCESS ............................................................................................................. 3 2.1. Admission to the Ward ............................................................................................................. 3 2.2. Assessment.................................................................................................................................. 4 2.3. Management using Chlordiazepoxide......................................................................................... 5 3. ASSESSMENT TOOLS............................................................................................................................ 7 3.1. AWS (Alcohol Withdrawal Scale) ............................................................................................ 7 3.2. AUDIT-C and AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test) ....................................... 8 3.3. Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) .................................................. 10 3.4. APQ (Alcohol Problem Questionnaire) ............................................................................... 13 3.5. SOCRATES 8A motivational assessment tool ........................................................................... 15 4. ALCOHOL WITHDRAWAL RECORDING FORMS ............................................................................... -

The Management of Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence in Primary Care 74 74

The management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence in primary care 74 74 1 Introduction 1 2 Detection and assessment 4 3 Brief interventions for hazardous and harmful drinking 7 4 Detoxification 11 5 Referral and follow up 16 6 Advising families 20 7 Information for discussion with patients and carers 21 8 Implementation, audit and further research 24 9 Development of the guideline 25 Annexes 28 Abbreviations 36 References 37 September 2003 - 2015 KEY TO EVIDENCE STATEMENTS AND GRADES OF RECOMMENDATIONS LEVELS OF EVIDENCE 1++ High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), or RCTs with a very low risk of bias 1+ Well conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias 1 - Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias 2++ High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort studies High quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal 2+ Well conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal 2 - Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal 3 Non-analytic studies, e.g. case reports, case series 4 Expert opinion GRADES OF RECOMMENDATION Note: The grade of recommendation relates to the strength of the evidence on which the recommendation is based. It does not reflect the clinical importance of the recommendation. -

A Report by the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman Nigel Newcomen CBE

A Report by the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman Nigel Newcomen CBE Investigation into the death of a man at hospital while in the custody of HMP Wormwood Scrubs in August 2012 1 Our Vision ‘To be a leading, independent investigatory body, a model to others, that makes a significant contribution to safer, fairer custody and offender supervision’ 2 This is the report of the investigation into the death of a man, who died in hospital in August 2012, while he was a prisoner at HMP Wormwood Scrubs. He was 43 years old and died as a result of a gastrointestinal bleed, caused by the perforation of a stomach ulcer. I offer my condolences to his family and friends. A review was undertaken of the clinical care the man received at received at Wormwood Scrubs. Wormwood Scrubs co-operated fully with the investigation. The man was remanded into custody on 10 August 2012. He was treated for alcohol withdrawal in the substance misuse unit. He had no symptoms of an intestinal ulcer until his collapse on 14 August. The emergency response was quick and effective. He was taken to hospital by the paramedics, but died shortly after. The investigation has not identified any concerns about the man’s care. We agree with the clinical reviewer that the standard of his healthcare at the prison was good and there was an appropriate medical response to his collapse. Sadly his death was neither predictable nor preventable. This version of my report, published on my website, has been amended to remove the names of the man who died and those of staff and prisoners involved in my investigation. -

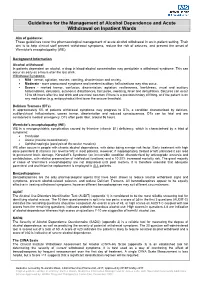

Guidelines for the Management of Alcohol Dependence and Acute Withdrawal on Inpatient Wards

Guidelines for the Management of Alcohol Dependence and Acute Withdrawal on Inpatient Wards Aim of guidance: These guidelines cover the pharmacological management of acute alcohol withdrawal in an in-patient setting. Their aim is to help clinical staff prevent withdrawal symptoms, reduce the risk of seizures, and prevent the onset of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE). Background Information Alcohol withdrawal In patients dependent on alcohol, a drop in blood-alcohol concentration may precipitate a withdrawal syndrome. This can occur as early as 6 hours after the last drink. Withdrawal Symptoms: Mild - tremor, agitation, nausea, vomiting, disorientation and anxiety. Moderate - more pronounced symptoms and transient auditory hallucinations may also occur. Severe - marked tremor, confusion, disorientation, agitation, restlessness, fearfulness, visual and auditory hallucinations, delusions, autonomic disturbances, fast pulse, sweating, fever and dehydration. Seizures can occur 12 to 48 hours after the last drink and are more common if there is a previous history of fitting, or if the patient is on any medication (e.g. antipsychotics) that lower the seizure threshold. Delirium Tremens (DTs) In approximately 5% of patients withdrawal symptoms may progress to DTs, a condition characterised by delirium, auditory/visual hallucinations, coarse tremor, disorientation and reduced consciousness. DTs can be fatal and are considered a medical emergency. DTs often peak later, around 96 hours. Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) WE is a neuropsychiatric complication caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, which is characterised by a triad of symptoms: Confusion Ataxia (muscle incoordination) Ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of the ocular muscles) WE often occurs in people with chronic alcohol dependence, with detox being a major risk factor.