The Tarikaka Settlement 85 Years of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore Wellington

EXPLORE Old Coach Rd 1 Makara Peak Mountain Bike Park This dual use track runs North SKYLINE and South along the ridge MAORI HISTORY AND KEY Wellington City Council set aside 200 TRACK between Old Coach Road in SIGNIFICANCE OUTER GREEN START/FINISH hectares of retired farmland South- EXPLORE Johnsonville and Makara Saddle BELT Carmichael St West of the city for a mountain bike in Karori. park in 1998. Volunteers immediately While European settlers named parts of the skyline, SKYLINE TRACK most of the central ridge was known to local Maori began development of the Makara Allow up to five hours to traverse 12kms of Wellington’s ridge tops 2 as Te Wharangi (broad open space). This ridge was Peak Mountain Bike Park by planting WELLINGTON following the Outer Green Belt onto Mt Kaukau, the Crow’s Nest, NORTHERN Truscott Ave not inhabited by Maori, but they traversed frequently trees and cutting new tracks. In the Discover Wellington’s Town Belt, reserves and walkways Kilmister Tops and Johnston Hill. Take time to indulge in the stunning WALKWAY Reserve and by foot when moving between Te Whanganui-a- Johnsonville Park first year, six tracks were built and rural, city and coastal views along the way. On a clear day, views of Tara and Owhariu. EXISTING TRACK 14,000 native seedlings planted. the Kaikoura ranges, the Marlborough Sounds, Wellington city and John Sims Dr Nalanda Cres A significant effort was also put into MT KAUKAU 3 dleiferooM dR harbour, and the Tararua and Orongorongo ranges will take your The Old Maori Trail runs from Makara Beach all the 1 9 POINTS OF controlling possums and goats, breath away. -

Khandallah, Broadmeadows, Ngaio, Crofton Downs and Kaiwharawhara

3 Management sector plans 3.1 Sector 1 Khandallah, Broadmeadows, Ngaio, Crofton Downs and Kaiwharawhara A unique feature of this sector is the harbour escarpment and the steep gullies off Onslow Road and Homebush Road. Where topography permits, the bush reserves have been developed to include tracks, with play areas, kick-about space or informal recreation space sometimes also provided. The Outer Green Belt (OGB) extends right down into Broadmeadows, Crofton Downs, Ngaio and Khandallah and provides a prominent natural setting for residential housing in this area and access to the extensive track system. The suburban reserves enhance ecological connectivity between the OGB and the harbour via the large natural gully reserves and smaller pockets of open space. This sector is adjacent to but does not include Trelissick Park or reserves in the Outer Green Belt. The open space network comprises: • One sport and recreation (community) park – Nairnville Park, which has a 3/4 size artificial field, three winter fields, two summer cricket blocks, a skateboard ramp and a community playground. Nairnville Recreation Centre is located on the park and provides a range of indoor recreation activities and programmes, changing rooms and public toilets during its hours of operation. • Kaiwharawhara Park on Hutt Road has one winter field and changing rooms. • Ngaio Tennis Club leases a recreation reserve on the corner of Crofton Road and Waikowhai Street. • 10 neighbourhood parks with a further two, Khandallah Park and play area and Silverstream Road play area, on the edge of this sector managed under the Outer Green Belt Management Plan. • Several large bush reserves. -

Wellington Walks – Ara Rēhia O Pōneke Is Your Guide to Some of the Short Walks, Loop Walks and Walkways in Our City

Detail map: Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori Hill) Detail map: Mount Victoria (Matairangi) Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. ade North North Wellington Otari-Wilton’ss BushBush OrientalOriental ParadePar W ADESTOWN WeldWeld Street Street Wade Street Oriental Bay Walks Grass St. WILTON Oriental Parade O RIEN T A L B A Y Ara Rēhia o Pōneke Northern Walkway PalliserPalliser Rd.Rd. Skyline Walkway To City ROSENEATH Majoribanks Street City to Sea Walkway LookoutLookout Rd.Rd. Te Ara o Ngā Tūpuna Mount Victoria Lookout MOUNT (Tangi(Tangi TeTe Keo)Keo) Te Ahumairangi Hill GrantGrant RoadRoad VICT ORIA Lookout PoplarPoplar GGroroveve PiriePirie St.St. THORNDON AlexandraAlexandra RoadRoad Hobbit Hideaway The Beehive Film Location TinakoriTinakori RoadRoad & ParliameParliamentnt rangi Kaupapa RoadStSt Mary’sMary’s StreetStreet OOrangi Kaupapa Road buildingsbuildings WaitoaWaitoa Rd.Rd. HataitaiHataitai RoadHRoadATAITAI Welellingtonlington BotanicBotanic GardenGarden A B Southern Walkway Loop walks City to Sea Walkway Matairangi Nature Trail Lookout Walkway Northern Walkway Other tracks Southern Walkway Hataitai to City Walkway 00 130130 260260 520520 Te Ahumairangi metresmetres Be prepared For more information Your safety is your responsibility. Before you go, Find our handy webmap to navigate on your mobile at remember these five simple rules: wcc.govt.nz/trailmaps. This map is available in English and Te Reo Māori. 1. Plan your trip. Our tracks are clearly marked but it’s a good idea to check our website for maps and track details. Find detailed track descriptions, maps and the Welly Walks app at wcc.govt.nz/walks 2. Tell someone where you’re going. -

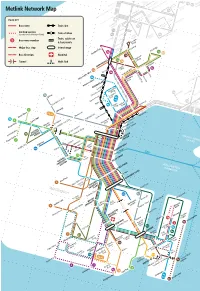

Metlink Network

1 A B 2 KAP IS Otaki Beach LA IT 70 N I D C Otaki Town 3 Waikanae Beach 77 Waikanae Golf Course Kennedy PNL Park Palmerston North A North Beach Shannon Waikanae Pool 1 Levin Woodlands D Manly Street Kena Kena Parklands Otaki Railway 71 7 7 7 5 Waitohu School ,7 72 Kotuku Park 7 Te Horo Paraparaumu Beach Peka Peka Freemans Road Paraparaumu College B 7 1 Golf Road 73 Mazengarb Road Raumati WAIKANAE Beach Kapiti E 7 2 Arawhata Village Road 2 C 74 MA Raumati Coastlands Kapiti Health 70 IS Otaki Beach LA N South Kapiti Centre A N College Kapiti Coast D Otaki Town PARAPARAUMU KAP IS I Metlink Network Map PPL LA TI Palmerston North N PNL D D Shannon F 77 Waikanae Beach Waikanae Golf Course Levin YOUR KEY Waitohu School Kennedy Paekakariki Park Waikanae Pool Otaki Railway ro 3 Woodlands Te Ho Freemans Road Bus route Parklands E 69 77 Muri North Beach 75 Titahi Bay ,77 Limited service Pikarere Street 68 Peka Peka (less than hourly, Monday to Friday) Titahi Bay Beach Pukerua Bay Kena Kena Titahi Bay Shops G Kotuku Park Gloaming Hill PPL Bus route number Manly Street71 72 WAIKANAE Paraparaumu College 7 Takapuwahia 1 Plimmerton Paraparaumu Major bus stop Train line Porirua Beach Mazengarb Road F 60 Golf Road Elsdon Mana Bus direction 73 Train station PAREMATA Arawhata Mega Centre Raumati Kapiti Road Beach 72 Kapiti Health 8 Village Train, cable car 6 8 Centre Tunnel 6 Kapiti Coast Porirua City Cultural Centre 9 6 5 6 7 & ferry route 6 H Coastlands Interchange Porirua City Centre 74 G Kapiti Police Raumati College PARAPARAUMU College Papakowhai South -

Stage 1 – Issues and Needs Analysis Summary of Submissions

Stage 1 – Issues and Needs Analysis Summary of Submissions Summary of Submissions 1 Executive summary This report summarises the submissions received as part of the first stage of consultation on the North Wellington Public Transport Study. The first stage of the study seeks to identify the public transport issues of the community and key stakeholders, particularly the passenger transport needs of the area. Key stakeholders including land transport providers, community groups, schools, affected residents and the general public were invited to participate in the consultation process. Notification of the process was undertaken in November 2005 through public notices in local papers, public displays at the Johnsonville Mall, Johnsonville, Khandallah and Ngaio Libraries, and a maildrop to over 15,000 households throughout the study area. In addition a webpage was set up to increase awareness and provide an ongoing reference point for interested parties. In total, just over 500 submissions were received from individuals, 5 from community groups and 4 from other organisations. Geographically, submissions were received from the suburbs within the study area. Khandallah, Ngaio, and Johnsonville (in order) were the largest submitter groups. 42 submitters did not specify a suburban address, 8 were from the wider Wellington Region and 1 was from a national organisation. Over half of submitters wished to be contacted further regarding the study. Key findings • Slightly over 50% of submitters use bus services while slightly under 50% use train services. • Approximately 85% walk to their public transport, 15% drive. • The top six issues raised by submitters were frequency of buses (18%), reliability (17%), route (17%), new trains (12%), and the rundown state of trains (10%). -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

2488 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 101 145434 Pearson, Tillyard Chapman, Clerk, 82 Lyall Parade, Lyall 227197 Pugh, William Rowe, Warehouseman, 35 White's Line West, Bay, Wellington. Lower Hutt. 423817 Pedersen, Philip Edmound, Slabby, Park House, Park Rd, 280315 Purcell, Rev. Philip, Clergyman, Catholic Presbytery, Upper Hutt. Knight's Rd, Lower Hutt. 383543 Pegler, Albert, Motor-trimmer, 4 Patrick St, Petone. 378390 Pye, John William, Process Worker, Tinakori Rd, Wellington. 215528 Peirse, Bruce Gilbert Pawley, Farm Hand, P.O. Box 1073, 099812 Radford, Ronald Leslie, Postman, Postmen's Branch, Wellington. G.P.O., Wellington. 300808 Pelham, Douglas James, Stable Hand, 32~York St, Moera, 421707 Railey, George, Watersider, 7 Jacobs Place, Wellington. Lower Hutt. 416375 Rainbow, Edwin Frederick, Seaman, Union Steam Ship Co., 253301 Perfect, Stanley Ernest, Sorter, 27 Plunket St, Kelburn, N.l. Ltd, Wellington. 281177 Perno, Charles, Garage-assistant, 336 High St, Lower Hutt. 085690 Rainey, Robert Henry Wilson, Clerk, Meteorological Office, 298638 Perrin, Roy Gihner, Soldier, Mobilization Camp, Trentham. Kelburn, Wellington. 247778 Perry, Albert William Joseph, Maintenance Engineer, 277760 Rait, Horace Francis, Hotel Porter, 33A Mulgrave St, 27 Totara St, Eastbourne. Wellington. 286354 Peterkin, Edward Roderick, 29 Ponsonby Rd, Karori, 404580 Raitt, David Muir, Builder, Hill House, Porirna. Wellington, W. 3 285390 Raitt, George, Apprentice Boilermaker, Eastwood Avenue, 263339 Petersen, Frederick Gordon, Filing Clerk, 260 The Terrace, Porirua. Wellington. 149268 Ramage, Colin Stokes, Clerk, 34 Glen Rd, Wellington. 425740 Petersen, Reinold Eric Mark, Assembler, care of A. Gripp, 159987 Ramsden, Edward, Sorter, 30 McColl St, Vogeltown, Wel Plimmerton. lington. 390878 Petrie, Graham Young, Salesman, 23 Epuni St, Wellington, 375233 Ramsden, Matthew Arthur, Furnishing Salesman, 121 C. -

The New Zealand Gazette. 195

JAN. 20.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 195 MILITARY AREA No. 5 (WELLINGTON)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 5 (WELLINGTON)-continued. 616986 McAdam, Derryck Roland, insurance clerk, 120 Richmond 47-9114 McDonald, Ivan Allan, warehouseman, Flat 3, Belvedere St., Petone. Flats, Austin St., Wellington. 498532 McAleese, James, barman, 238 Tinakori Rd., Wellington. 469623 Macdonald, James Third, caretaker, 18 Garden Rd., North 615408 McAlister, Desmond, musterer, Fort Dorset, Wellington. land, Wellington. 513057 McAllister, Donald Charles William, seaman, 42 Rose St., 4 74979 McDonald, Keith Hargreaves, commercial traveller, 4 Gore Wadestown, Wellington. St;, Seatoun, Wellington. 586129 Macan, Charles Davis, public servant, 37 Adams Tee., 619212 McDonald, Neil Ross, clerk, 23 Upland Crcs., Kelburn, Wellington. Wellington W. 1. 467967 McAnerin, Cecil William, welder mechanic, 4 Hinau Rd., 609060 Macdonald, Peter, shift pitman, 47 Balfour St., Newtown, Hataitai, Wellington. Wellington. 469156 McArdle, John, despatch clerk, 14 Beaumont Ave., Lower 544216 McDonnell, Howard William, coppersmith, 18 Tama, St., Hutt. Lower Hutt. 4 79614 McArley, Thomas Leo, architect, 80 Ghuznee St., Wellington. 491476 Mac Dougall, Gordon Ross, storeman-driver, 64 Maupuia Rd., 479615 Macarthur, Colin Turnbull, X-ray engineer, 21 Amritsar Wellington E. 4. St., Khandallah, Wellington. 618074 McDougall, John Colin, dental student, 115 Melbourne Rd., 515373 McArthur, William, salesman, 12 Veronica St., Brooklyn, Wellington S. 2. Wellington. 491481 McDowell, Allen, fitter and turner, 2 St. Ronans Ave .. Lower 436505 McArtncy, Robert John, lorry-driver, 215 Vivian St., Hutt. Wellington. 601440 McDowell, Douglas Herbert, bus-driver, 44A Pretoria St., 500194 McAuley, Christopher Richard James, labourer, 54 Strath Lower Hutt. more Ave., Wellington. 583638 McEnnis, James Daniel, civil servant, 7 Brougham Ave., 492137 Macbrayne, James, electric welder, 40 Stone St., Miramar, Wellington E. -

Combined Earthquake Hazard Map Wellington City

Combined earthquake hazard map Wellington City Slope failure Key to slope failure susceptibility zones Very high High Moderate Low Very low Churton Park Grenada Village Johnsonville Newlands Raroa Liquefaction potential Key to liquefaction potential zones High Moderate Low Variable Khandallah No Ngaio Crofton Downs Kaiwharawhara Wadestown Northland Groundshaking Key to ground shaking hazard High Karori Moderate Low Variable No Kelburn Roseneath KEY Mt Victoria Hazard index Low Hataitai Mt Cook Mitchelltown Brooklyn Medium Newtown Kilbirnie Miramar Rongotai Tsunami and fault lines Berhampore High Key to tsunami inundation and faultline Lyall Bay Seatoun Land that will be inundated Roads Major fault Land outside study area Island Bay Owhiro Bay N Major fault Background statement Earthquake Hazard Mitigation Measures In recognition of the earthquake hazard in the Region, the Greater Wellington Regional Council has carried out studies on ground surface rupture from active faulting, ground shaking, liquefaction potential and associated ground damage, slope failure and tsunami inundation (Wellington Harbour). Single factor hazard maps have been produced by Greater Wellington for each of these earthquake hazards. Hazard Effect on ground Effect on Mitigation options: Mitigation options: planned This map sheet is part of a series of four map sheets showing the combined earthquake hazard for the main urban areas in the western part of the Wellington facilities existing facilities facilities Region. The map series is one of Greater Wellington’s natural hazard education and awareness initiatives. Fault Ground disturbances vertically and Upheaval, tearing apart, 1. Verify. 1. Verify. The combined earthquake hazard map is a generalised map of earthquake hazard refl ecting possible effects on a typical range of facilities (buildings, roads, horizontally over a zone depends on movement of foundations, 2. -

KHANDALLAH SCHOOL New Handbook

Tātai ki te Rangi Parent / Family / Whanau Handbook 2017 ‘Inspiring Future Stars’ Page 1 ‘Inspiring Future Stars’ Page 2 ‘Inspiring Future Stars’ Page 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 OUR SCHOOL ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 GENERAL ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 SCHOOL ORGANISATION .............................................................................................................................................. 6 ENROLMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABOUT KHANDALLAH SCHOOL ..................................................................................................................................... 7 BOARD OF TRUSTEES .................................................................................................................................................... 7 LEARNING PROGRAMMES ............................................................................................................................................ 8 SCHOOL OPERATION.................................................................................................................................................. -

SUBMISSION Khandallah Medium Density Housing and Town Centre Plans

SUBMISSION Khandallah Medium Density Housing and Town Centre Plans From: Khandallah Residents Group c/o 53 Cashmere Avenue Khandallah Wellington 6035 [email protected] Contacts: Diane Calvert Ph 029 971 8994 Christine McKenna Ph 021 107 1675 This submission is made on behalf of the above working group. There are 11 members on the working group, and 305 people who have chosen to be on our database. Summary 1. To be clear, the Khandallah Residents group supports housing choice and supply solutions that best meet the current and future needs of our community. 2. Khandallah Residents Group is opposed to Council’s plan for medium-density housing in Khandallah as an appropriate solution to meeting housing choice and supply needs. 3. The need for additional housing in Khandallah is modest and does not justify the introduction of medium-density housing of the type and scale proposed. Rather than copying housing solutions from larger and different types of cities, we should be more innovative and devise answers appropriate to the scale of the future need and that fit with our community. 4. We have significant concerns about the quality of the consultation process and the flawed and leading submission form. 5. The town planning process needs to take into account the whole suburb and its infrastructure needs and be undertaken in collaboration with the community. This should culminate in a holistic plan for the future of Khandallah. Only then should a Khandallah Design Guide should be developed (not the other way around as has already occurred). 6. Local residents highly value Khandallah’s character (e.g. -

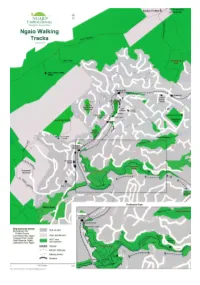

Walking Tracks Running from the Lower Lower the from Running Tracks Walking and Reserves Bush Accessible Many

www.ngaio.org.nz www.metlink.org.nz (Kaukau is a corruption of kaka, the native parrot). native the kaka, of corruption a is (Kaukau Open 1- 4pm Sunday 4pm 1- Open ph 0800 801 700 801 0800 ph and bird snaring was done on the slopes of Mt Kaukau. Kaukau. Mt of slopes the on done was snaring bird and www.teararoa.org.nz 86 Khandallah Road Khandallah 86 Metlink has train and bus timetables and journey planner. journey and timetables bus and train has Metlink in the present Kenya Street - Trelissick Crescent area area Crescent Trelissick - Street Kenya present the in Te Araroa Trail site Trail Araroa Te · · Onslow Historical Society Historical Onslow · to Khandallah. The Kaiwharawhara Pa had gardens gardens had Pa Kaiwharawhara The Khandallah. to Several bus routes connect from Wellington to Ngaio. to Wellington from connect routes bus Several http://wellington.govt.nz route of the present Bridle Track from Winchester Street Street Winchester from Track Bridle present the of route Cummings Park Library, Ngaio Library, Park Cummings · Otari. There was also a track to the north following the the following north the to track a also was There Otari. parks, reserves and heritage trails. trails. heritage and reserves parks, www.tranzmetro.co.nz www.tranzmetro.co.nz www.tracks.org.nz and Makara Pas via various tracks that passed near near passed that tracks various via Pas Makara and and brochures on tracks, walkways, walkways, tracks, on brochures and Downs, Ngaio, Awarua Street, Simla Crescent and Box Hill. Hill. Box and Crescent Simla Street, Awarua Ngaio, Downs, Tracks Tracks · Wellington City Council has maps maps has Council City Wellington · Kaiwharawhara Stream. -

Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This Is Part 1 of a Two Part Trail

Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This is Part 1 of a two part trail. Part 2 is contained in a separate booklet. This part of the trail will take two to three hours to drive. There is some walking involved as well but it is of a generally easy nature. It features the southern suburbs - Kaiwharawhara, Ngaio, Crofton Downs, Wilton and Wadestown - that largely surround and overlook the Kaiwharawhara Stream. Part 2 follows the Old Porirua Road through Ngaio, Khandallah and Johnsonville, Glenside and Tawa with deviations to Ohariu, Grenada Village, Paparangi and Newlands. The trail finishes at Ngauranga. Main features of the trail Bridle Track Kaiwharawhara Magazine Crofton Wellington-Manawatu Railway (Johnsonville Line) Wilton House Panels describing the history of the major centres Key Registered as a historic place by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust / Pouhere Taonga Part 1 Listed as a heritage item in the Wellington City District Plan Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This is Part 1 of a two part trail. Part 2 is contained in a separate booklet. This part of the trail will take two to three hours to drive. There is some walking involved as well but it is of a generally easy nature. It features the southern suburbs - Kaiwharawhara, Ngaio, Crofton Downs, Wilton and Wadestown - that largely surround and overlook the Kaiwharawhara Stream. Part 2 follows the Old Porirua Road through Ngaio, Khandallah and Johnsonville, Glenside and Tawa with deviations to Ohariu, Grenada Village, Paparangi and Newlands.