WATER QUALITY SUMMARY Grand Traverse Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscriptsummer 2019 Volume 71

landscriptSUMMER 2019 Volume 71 Lower Woodcock Lake – A Gem in the Platte Watershed A New Preserve on Torch Lake Arcadia Marsh UA Trail Open PHOTO BY D SMITH GTRLC.ORG 1 Protecting significant natural, scenic and farm lands — and advancing stewardship — now and for future generations. PHOTO BY DEKE LUDWIG A Letter from Glen Chown FRIENDS, Not long ago, I came across a quote from the there are the organized trail-building work days We are setting a new standard of excellence legendary naturalist Sir David Attenborough that at places like the newly opened Maplehurst in design and quality of construction that is really stuck with me: “No one will protect what Natural Area where people joyfully contribute exemplified at places like Arcadia Marsh (page they don’t care about, and no one will care about sweat equity to make a tangible impact. XX). And there is a deeply spiritual dimension what they have never experienced.” to “access to nature” investments that I did Since the beginning of the not fully anticipate when we envisioned this As we continue to make campaign, our dedicated campaign. I will never forget the comment of great progress with our staff and board have one dedicated supporter after stepping onto ambitious Campaign for worked hard to make the marsh boardwalk for the very first time. Generations goals, I feel sure that our supporters, “I feel like I am walking on water. What the overjoyed at the truly partners, and the general Conservancy has done here is truly miraculous,” remarkable projects we’ve public have opportunities she exclaimed, her face radiant. -

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics Lake Michigan is a dynamic deepwater oligotrophic ecosystem that supports a diverse mix of native and non-native species. Although the watershed, wetlands, and tributaries that drain into the open waters are comprised of a wide variety of habitat types critical to supporting its diverse biological community this section will focus on the open water component of this system. Watershed, wetland, and tributaries issues will be addressed in the Northeastern Morainal Natural Division section. Species diversity, as well as their abundance and distribution, are influenced by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors that define a variety of open water habitat types. Key abiotic factors are depth, temperature, currents, and substrate. Biotic activities, such as increased water clarity associated with zebra mussel filtering activity, also are critical components. Nearshore areas support a diverse fish fauna in which yellow perch, rockbass and smallmouth bass are the more commonly found species in Illinois waters. Largemouth bass, rockbass, and yellow perch are commonly found within boat harbors. A predator-prey complex consisting of five salmonid species and primarily alewives populate the pelagic zone while bloater chubs, sculpin species, and burbot populate the deepwater benthic zone. Challenges Invasive species, substrate loss, and changes in current flow patterns are factors that affect open water habitat. Construction of revetments, groins, and landfills has significantly altered the Illinois shoreline resulting in an immeasurable loss of spawning and nursery habitat. Sea lampreys and alewives were significant factors leading to the demise of lake trout and other native species by the early 1960s. -

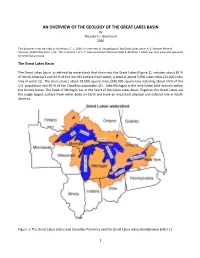

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

Northwest Region Michigan

Northwest Region Michigan Michigan’s Northwest Region offers a rich blend of adventure, relaxation and breathtaking natural attractions, making it a must for your travel bucket list. Don’t miss “The Most Beautiful Place in America,” also known as Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes National Lakeshore. In addition to epic sand dunes, the park features forests, historical sites and ancient glacial phenomena. A drive along M-22 will prove though that this is no diamond in the rough – Lake Michigan and the countless inland lakes in the region offer a chance to experience a Lake Effect like no other. CAMPGROUND LOCATIONS: 1. Wilderness State Park Campground Why We Love This Campground: Wilderness State Park offers visitors a variety of year-round recreational activities within its over 10,000 acres. Wilderness areas and 26 miles of beautiful Lake Michigan shoreline provide great places to observe nature from the numerous trails throughout the park. Max RV Length: 45' # Of Sites: 250 Fee: $22-$45 Address: 903 Wilderness Park Dr. Carp Lake MI Contact: (231) 436-5381 2. Petoskey State Park Campground Why We Love This Campground: The Oden Fish Hatchery is a short drive from the park and one of the most advanced facilities of its kind. For anyone interested in how brook and brown trout are raised, this is the premier destination. Max RV Length: 40' # Of Sites: 180 Fee: $31-$37 Address: 2475 M-119 Hwy. Petoskey MI Contact: (231) 347-2311 3. Young State Park Campground Why We Love This Campground: Young State Park on beautiful Lake Charlevoix spans over 560 acres and is a mix of gently rolling terrain, lowlands and cedar swamp. -

Grand Traverse Bay Watershed Survey of Experiences with Climate Change and Global Warming: a Summary

(Terry W. Phipps. Courtesy of Michigan Travel Bureau) Grand Traverse Bay Watershed Survey of Experiences with Climate Change and Global Warming: A Summary (Courtesy of Michigan Travel Bureau) Experiences with Climate Change in the Grand Traverse Bay Watershed Patricia E. Norris, Brockton C. Feltman and Jessica L. Batanian Department of Community Sustainability, Michigan State University April 2015 Introduction In late July 2014, we initiated a survey of residents in the Grand Traverse Bay Watershed as part of a larger project exploring implications of climate change in the region and opportunities for adaptation at community and watershed levels. Early scientific and policy discussions about climate change focused largely on gradual warming planet-wide, its causes, and its impacts. In recent years, however, discussions have become more nuanced and reveal a greater understanding of the many ways in which climate change will affect weather patterns generally, as well as many biotic and abiotic resources specifically. Various types of data collected in the Grand Traverse Bay (GTB) region show evidence of changes in the environment driven by shifts in climate conditions and the resulting weather patterns. Our survey asked residents what, if any, changes they have observed in a series of factors influenced by climate such as frequency and duration of rain events, ice cover on lakes, and length of growing season. We also asked a series of questions about perceptions of global warming, more generally. This report provides a summary of those survey results. Analysis of the survey data is underway to explore a number of different questions. These analyses will be described briefly at the end of this report. -

2011 Annual Beach Monitoring Report

MI/DEQ/WRD-12/034 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY WATER RESOURCES DIVISION AUGUST 2012 STAFF REPORT MICHIGAN BEACH MONITORING YEAR 2011 ANNUAL REPORT INTRODUCTION The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), Surface Water Quality Monitoring Program, is summarized in the January 1997 report entitled, “A Strategic Environmental Quality Monitoring Program for Michigan’s Surface Waters” (Strategy) (MDEQ, 1997). The objectives of the beach monitoring component of the Strategy are listed below: 1. Assist local health departments to implement and strengthen beach monitoring programs. 2. Create and maintain a statewide database. 3. Determine whether waters of the state are safe for total body contact recreation. 4. Compile data to determine overall water quality. 5. Evaluate the effectiveness of MDEQ programs in attaining Water Quality Standards (WQS) for pathogen indicators. 1. ASSIST LOCAL HEALTH DEPARTMENTS TO IMPLEMENT AND STRENGTHEN BEACH MONITORING PROGRAMS Beach Monitoring The monitoring of beaches in Michigan is voluntary and is conducted by the local health departments. Health departments are required to comply with Michigan’s WQS according to R 333.12544 of the Public Health Code, 1978 PA 368 (Act 368), as amended. According to R 333.12541 of Act 368, a local health officer or an authorized representative of a local health department that conducts tests at bathing beaches is required to notify the MDEQ and other entities of the test results within 36 hours of conducting a test or evaluation. This rule also states that the local health department may petition the circuit court for an injunction ordering the owners of a beach to close the beach. -

Mackinac County

MACKINAC COUNTY S o y C h r t o u Rock r u BETTY B DORGANS w C t d 8 Mile R D n 6 mlet h o i C d t H o y G r e e Island LANDING 4 CROSSING B u N a Y o d Rd R R R 4 e 8 Mile e y 4 1 k t R k d n 2 ix d t S 14 7 r i Advance n p n 17 d i m Unknow d o e a F u 5 C 123 t e T 7 x k d y O l a o s e i R i R 1 Ibo Rd 1 r r e r Sugar d C M o d Island R a e d R 4 p y f e D c E e S l e n N e i 4 C r a R E R o Y d R L 221 e v a i l 7 R h d A i w x d N i C n S a e w r d g d p e n s u d p 5 a c o r R a r t e B U d d T Island in t g G i e e a n r i g l R R n i o R a d e e R r Rd d o C C o e d d 9 Mile e c 4 r r g k P r h d a L M e n M t h R v B W R R e s e 2 r R C R O s n p N s l k n RACO ea l e u l 28 o ROSEDALE n i R C C d 1 y C l i ree a e le Rd e k a U d e v i 9 Mi e o S y r S a re e d i n g C R R Seney k t ek N e r h C Shingle Bay o U e i u C s R D r e U essea S Sugar B d e F s h k c n c i MCPHEES R L n o e f a a r s t P x h B y e d ut a k 3 So i r k i f u R e t o 0 n h a O t t 1 3 R r R d r r A h l R LANDING 3 M le 7 7 s i T o 1 E d 0 M n i 1 C w a S t U i w e a o s a kn ECKERMAN t R R r v k C o n I Twp r C B U i s Superior e e Island h d d e b Mile Rd r d d Mile Rd 10 e a S f 10 o e i r r q l n s k i W c h n d C u F 3 Columbus u T l McMillan Twp ens M g C g a h r t E a h r 5 Mo reek R n E T 9 H H q m REXFORD c e i u a DAFTER n R W r a l k 5 o M r v Twp Y m r h m L e e C p e i e Twp F s e STRONGS d i Dafter Twp H ty Road 462 East R t d e a Coun P n e e S n e r e v o v o s l d C i R m s n d T o Twp h R t Chippewa l p R C r e NEWBERRY U o e R a n A -

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan Was Granted

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan was granted statehood on January 26, 1837, Michigan also acquired ownership of the Great Lakes' bottomlands under the equal footing doctrine.1 However before Michigan could become a state, the United States first had to acquire title from us (Ottawa and Chippewa bands) because Anglo-American law acknowledged that we owned legal title as the aboriginal occupants of the territory we occupied. But when we agreed to cede legal title to the United States in the March 28, 1836 Treaty of Washington ("1836 Treaty", 7 Stat. 491), we reserved fishing, hunting and gathering rights. Therefore, Michigan's ownership of both the lands and Great Lakes waters within the cession area of the 1836 Treaty was burdened with preexisting trust obligations with respect to our treaty-reserved resources. First, the public trust doctrine imposes a duty (trust responsibility) upon Michigan to protect the public trust in the resources dependent upon the quality of the Great Lakes water.2 In addition, Art. IV, § 52 of Michigan's Constitution says "conservation…of the natural resources of the state are hereby declared to be of paramount public concern…" and then mandates the legislature to "provide for the protection of the air, water and other natural resources from 3 pollution, impairment and destruction." 1 The State of Michigan acquired title to these bottomlands in its sovereign capacity upon admission to the Union and holds them in trust for the benefit of the people of Michigan. Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois, 146 U.S. 387, 434-35 (1892); Nedtweg v. -

Antrim County

Economic Profile – Antrim County Updated 2016 County Highlights Antrim County is located in the northwestern part of the lower peninsula, east of Lake Michigan and Grand Traverse Bay and bordered on the west by the Mackinaw State Forest, also referred to as the Jordan River Valley. The county has a total area of 602 square miles of which 477 square miles is land and 125 square miles is water. The county contains 45 lakes, has 24 miles of Lake Michigan shoreline, and rivers covering 65 miles of waterways throughout the area. The county has nearly 44,000 acres of state forest land, the Grass River Natural Area and Wilcox-Palmer-Shah Nature Preserve. Most notable of the lakes is Torch Lake, considered to be one of the most beautiful lakes in the world. Torch Lake is on a chain of lakes that runs from Bellaire to Elk Rapids. North of Bellaire is another chain of lakes that goes from there through Central Lake and Ellsworth, with the largest of these being Intermediate Lake. Paddle Antrim was created in 2015 with a primary purpose of supporting efforts to maintain water quality in the rivers, lakes, and streams in Antrim County. Mancelona, located in the southwest corner of the county, on US-131, is home to the annual White Pine Stampede, Bass Festival and Deadman’s Hill Scenic Overlook. The county also has over a dozen fine golf courses, and is a major ski resort area, home to Shanty Creek Resort. The county is the 8th smallest in the state and holds its county seat in Bellaire. -

Naming Rationale

Naming Rationale Label-wise, the goal of the map is to illuminate the various landforms of Michigan, of which many residents are quite unaware. It should inform them of existing toponyms, as well as provide new toponyms for noteworthy features which don’t seem to have any. Landform toponyms can be approached from a folk or a technical perspective. A local might refer to the Yellow Hills that lay beside the Green Plain, whereas a physical geographer would recognize the glacial origins of these features and have good reason to call them the Yellow Moraine, next to the Green Glacial Lake Plain. My chosen perspective is folk toponymy. However, for many features in Michigan such names are lacking or poorly-attested, whereas technical names are much more common (experts think about landforms much more than other residents). Therefore I have sometimes borrowed from the list of technical names, modifying them at times to be more folk-like. For some features, the sources I have disagree as to their name or extent. I have done my best to mediate disputes. Other features have names that appear only on a single source, invented by mapmakers who saw landforms languishing in anonymity. I have propagated these names where they seemed sensible to me, and coined some of my own. All toponyms have to start somewhere. The result is a mixture of folk and technical, existing and newly-coined. Another cartographer would, given the same starting materials, produce a different result. I hope though, that my decisions seem justifiable and sound. List of Names and Sources In the pages that follow, I have compiled my notes and sources for every label on the map. -

Lighthouses – Clippings

GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION MILWAUKEE PUBLIC LIBRARY/WISCONSIN MARINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY MARINE SUBJECT FILES LIGHTHOUSE CLIPPINGS Current as of November 7, 2018 LIGHTHOUSE NAME – STATE - LAKE – FILE LOCATION Algoma Pierhead Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan - Algoma Alpena Light – Michigan – Lake Huron - Alpena Apostle Islands Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Apostle Islands Ashland Harbor Breakwater Light – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Ashland Ashtabula Harbor Light – Ohio – Lake Erie - Ashtabula Badgeley Island – Ontario – Georgian Bay, Lake Huron – Badgeley Island Bailey’s Harbor Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bailey’s Harbor Range Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bala Light – Ontario – Lake Muskoka – Muskoka Lakes Bar Point Shoal Light – Michigan – Lake Erie – Detroit River Baraga (Escanaba) (Sand Point) Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Sand Point Barber’s Point Light (Old) – New York – Lake Champlain – Barber’s Point Barcelona Light – New York – Lake Erie – Barcelona Lighthouse Battle Island Lightstation – Ontario – Lake Superior – Battle Island Light Beaver Head Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Beaver Island Beaver Island Harbor Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – St. James (Beaver Island Harbor) Belle Isle Lighthouse – Michigan – Lake St. Clair – Belle Isle Bellevue Park Old Range Light – Michigan/Ontario – St. Mary’s River – Bellevue Park Bete Grise Light – Michigan – Lake Superior – Mendota (Bete Grise) Bete Grise Bay Light – Michigan – Lake Superior -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey