The Jlate Piano Works of Franz Liszt"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Late Works for Piano Solo, 1870–1886 Selected Late Works for Piano Solo, 1870–1886 Edited by Nicholas Hopkins Edited by Nicholas Hopkins

PL1058 Franz Liszt Franz Liszt Selected Late Works for Piano Solo, 1870–1886 Selected Late Works for Piano Solo, 1870–1886 Edited by Nicholas Hopkins Edited by Nicholas Hopkins The final years in the life of Franz Liszt were a period of great misfortune and distress. Much of his music from this time, largely sacred choral works and music for solo piano, 1870–1886 / ed. Hopkns Solo, for Piano Works Late Liszt: Selected Franz had been received with vitriolic criticism, hostility and public disinterest. He had endured a number of personal losses, including the deaths of his son Daniel and of his eldest daughter Blandine, as well as of a number of close friends and colleagues. A growing estrangement with his daughter Cosima subjected him to a deep depression that followed him for the remainder of his life, as did an abortive marriage to Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. He had become obsessed with death and even contemplated suicide on several occasions. All of these mounting setbacks would take their toll, and the aged Liszt would be subjected to critical bouts of depression, self-doubt and lethargy. Alcohol would become a comfort and eventually an addiction. His physical health would inevitably be affected. His eyesight failed over the course of his final years, to the extent that he was unable to maintain correspondence or to compose. He additionally suffered from ague and dropsy, an accumulation of excess water that resulted in extreme swelling. Chronic dental problems brought about the loss of most of his teeth, and warts developed on his face, a result of tumorous growths that are unequivocally displayed in his late portraits. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Franz Liszt: Spiritual Seeker

GOING BEHIND THE NOTES: EXPLORING THE GREAT PIANO COMPOSERS AN 8-PART LECTURE CONCERT SERIES FRANZ LISZT: SPIRITUAL SEEKER Dr. George Fee www.dersnah-fee.com Performance: Sancta Dorothea (1877) Liszt’s Life (1811-1886) Liszt’s Music Performance: Petrarch Sonnet No. 104 (1855) The Man Liszt Fact vs. Fiction Performance: Transcription of Robert Schumann’s Widmung (1848) 10 Minute Break Playing Liszt’s Music Liszt’s Later Years Liszt’s Late Piano Music Performance: Five Hungarian Folk Songs (1873) Csárdás obstiné (1884) Performance: La Lugubre Gondola no.2 (1882) Liszt’s Philosophy of Music c Performance: Les jeux d’eaux a la Villa d’Este (1877) Performance: Sursum Corda (1877) HIGHLY RECOMMENDED READING ON LISZT Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt. Alfred A. Knopf, Vol. 1, 1983; Vol. 2, 1989; Vol. 3, 1996. LISZT’S MOST SIGNIFICANT PIANO WORKS Annees de pelerinage (Years of Pilgrimage) 1st year: Switzerland 2nd year: Italy 3rd year: Italy Ballade #2 Funerailles Two Legends: #1 St.Francis of Assisi’s Sermon to the Birds; #2 St.Francis of Paola Walking on the Waves Mephisto Waltz #1 Sonata in B Minor LISZT’S BEST KNOWN NON- SOLO PIANO WORKS 13 Symphonic Poems (especially #3 ,” Les Preludes” ) A Faust Symphony Piano Concerti in E Flat Major and A Major Petrarch Sonnet 104 I find no peace, and yet I make no war: and fear, and hope: and burn, and I am ice and fly above the sky, and fall to earth, and clutch at nothing, and embrace the world. One imprisons me, who neither frees nor jails me, nor keeps me to herself nor slips the noose: and Love does not destroy me, and does not loose me, wishes me not to live, but does not remove my bar. -

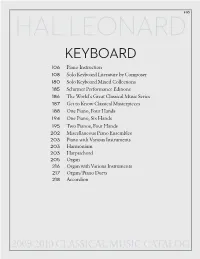

Keyboard: 6/18/09 3:51 PM Page 105 HAL LEONARD105 KEYBOARD

76164 4 Classical_Keyboard: 6/18/09 3:51 PM Page 105 HAL LEONARD105 KEYBOARD 106 Piano Instruction 108 Solo Keyboard Literature by Composer 180 Solo Keyboard Mixed Collections 185 Schirmer Performance Editions 186 The World’s Great Classical Music Series 187 Get to Know Classical Masterpieces 188 One Piano, Four Hands 194 One Piano, Six Hands 195 Two Pianos, Four Hands 202 Miscellaneous Piano Ensembles 203 Piano with Various Instruments 203 Harmonium 203 Harpsichord 205 Organ 216 Organ with Various Instruments 217 Organ/Piano Duets 218 Accordion 2009-2010 CLASSICAL MUSIC CATALOG 76164 4 Classical_Keyboard: 6/18/09 3:51 PM Page 106 106 PIANO INSTRUCTION ______49005413 Easy Baroque Piano Music (Emonts) PIANO INSTRUCTION Schott ED5096 ...........................................................$13.95 ______49005116 Easy Piano Pieces from Bach’s Sons to Beethoven ADAMS, BRET (ed. Emonts) Schott ED4747 .....................................$13.95 ______50006170 12 Primer Theory Papers ______49005117 Easy Romantic Piano Music – Volume 1 (ed. Emonts) Schirmer SG2566 ..........................................................$4.95 Schott ED4748 ...........................................................$13.95 BENNER, LORA ______49007882 Easy Romantic Piano Music – Volume 2 (ed. Emonts) Schott ED8277 ...........................................................$13.95 ______50330220 Theory for Piano Students Book 1 From Bartók to Stravinsky Easy Modern Piano Pieces Schirmer ED2511 ..........................................................$9.95 ______49005136 -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 583. - 2 - February 2014 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Aaberg, Philip: High Plains - comp.pno (1985) S WINDHAM HI WH 1037 A 12 2 Ackerman, William: Conferring with the Moon - Bisharat vln, Manring bass, WINDHAM HI WH 1050 A 12 comp.charango, etc (1986) S 3 Amirov: The 1001 Nights ballet - Kasimova, etc, cond.Rzaev 1982 S 2 x MELODIYA C10 19373 A 20 4 Antheil, George: Pno Sonata 4/ Bax: Elegiac Trio/ Debussy: Syrinx - F.Marvin pno, ALCO ALP 1007 A– 10 Ruderman fl, M.Thomas vla, Craft hrp (red vinyl) 10" 5 Arkhimandritov: Toulouse-Lautrec/P.Gekker: Spring Games/L.Balay: Lagushka- MELODIYA C10 22755 A 20 Puteshestvennitsa - cond.Sinaysky, Serov, Churzhel 1984, 1983 S 6 Artiomov: Vars for Fl; Invocations for Sop & Percs; Awakening for 2 Vlns; Totem for MELODIYA C10 18981 A 10 Percs - Krysa, Grindenko vln, Davydova sop, perc ens, Korneyev fl 1976-82 S 7 Artyomov: Sym of Elegies - Grindenko, Krysa vln, Lithuanian ChO, Sondeckis 1983 MELODIYA C10 20241 A 12 S 8 Arutyunian: Tr Con V.Kruikov: Concert Poem for Tr & Orch/Veinberg: Tr Con - ETERNA 826402 A 10 GD3 Dokshitser, cond.Rozhdestvensky, Juraitis S 9 Barber: Medea, Capricorn Concerto - cond.Hanson (EMI pressing) S MERCURY AMS 16096 A 15 EM1 10 Bialas, Gunther: Indianische Kantata (H.Brauer, cond.G.Konig)/F.Martin: Petite Sym DGG 4090 A 12 GY3 CVoncertante (cond.Fricsay) (gatefold) 11 Billings, William: Prise, Prayer & Patriotism - St.Columbia Singers, cond.Beale RPC Z 457621 A++ 12 S 12 Bloch: Sinfonia Breve/ Peterson: Free Variations - Minneapolis SO, cond.Dorati MERCURY -

72001 for PDF 11/05

EARL WILD LISZT THE 1985 SESSIONS DISC 1 From “Années de Pèlerinage” Second Year: Italy (S161/R10b) 1 Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi Sonata) 15:58 [“Dante Sonata”] (Andante maestoso - Presto agitato assai - Tempo I (Andante) - Andante (quasi improvvisato) - Andante - Recitativo - Adagio - Allegro moderato - Più mosso - Tempo rubato e molto ritenuto - Andante - Più mosso - Allegro - Allegro vivace - Presto - Andante (Tempo I)) 2 Sonetto 47 del Petrarca 6:20 (Preludio con moto - Sempre mosso con intimo sentimento) 3 Sonetto 104 del Petrarca 6:31 (Agitato assai - Adagio - Agitato) 4 Sonetto 123 del Petrarca 7:04 (Lento placido - Sempre lento - Più lento - (Tempo iniziale)) From “Années de Pèlerinage” Third Year (S163/R10e) 5 Les jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este 7:41 (Fountains of the Villa d’Este) (Allegretto) 6 Ballade No.2 in B minor (S171/R16) 13:59 (Allegro moderato - Lento assai - Tempo I - Lento assai - Allegretto - Allegro deciso - Allegretto - Allegretto sempre legato - Allegro moderato - Un poco più mosso - Andantino) From “Liebesträume, 3 Notturnos” (S541/R211) 7 Liebesträume (Notturno) No.2 in E flat Major (2nd Version) 4:27 (“Seliger Tod”) (Quasi lento, abbandonandosi) 8 Liebesträume (Notturno) No.3 in A flat Major 4:26 (“O lieb, so lang du lieben kannst!”) (Poco allegro, con affetto) 9 Concert Étude No.3 in D flat Major (“Un Sospiro”) (S144/R5) 5:14 (Allegro affettuoso) Total Playing Time : 72:16 – 2 – DISC 2 Bach/Liszt: Fantasia and Fugue in G minor (S463/R120) 11:12 1 Fantasia (Grave) 5:49 2 Fugue (Allegro) 5:23 Sonata -

Franz Liszt: the Ons Ata in B Minor As Spiritual Autobiography Jonathan David Keener James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2011 Franz Liszt: The onS ata in B Minor as spiritual autobiography Jonathan David Keener James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Music Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Keener, Jonathan David, "Franz Liszt: The onS ata in B Minor as spiritual autobiography" (2011). Dissertations. 168. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/168 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Franz Liszt: The Sonata in B Minor as Spiritual Autobiography Jonathan David Keener A document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2011 Table of Contents List of Examples………………………………………………………………………………………….………iii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….v Introduction and Background….……………………………………………………………………………1 Form Considerations and Thematic Transformation in the Sonata…..……………………..6 Schumann’s Fantasie and Alkan’s Grande Sonate…………………………………………………14 The Legend of Faust……………………………………………………………………………………...……21 Liszt and the Church…………………………………………………………………………..………………28 -

The Poetic Ideal in the Piano Music of Franz Liszt: a Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals Of

6 7 THE POETIC IDEAL IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF FRANZ LISZT: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF MUSIC BY MOZART, BEETHOVEN, SCHUBERT, CHOPIN, BRAHMS, AND CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN AND NORTH AMERICAN COMPOSERS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Gladys Lawhon, M. A. Denton, Texas December, 1972 Lawhon, Gladys, The Poetic Ideal in the Piano Music of Franz Liszt: A Lecture Recital, Together with Two Solo Recitals and a Chamber Music Recital. Doctor of Musical Arts (Piano Performance), December, 1972, 23 pp., 8 illustrations, bib- liography, 56 titles. The dissertation consists of four recitals: one chamber music recital, two solo recitals, and one lecture recital. The chamber music program included a trio with the violin and cello performing with the piano. The repertoire of all of the programs was intended to demonstrate a variety of types and styles of piano music from several different historical periods. The lecture recital, "The Poetic Ideal in the Piano Music of Franz Liszt," was an attempt to enter a seldom- explored area of Liszt's musical inspiration. So much has been written about the brilliant and virtuosic compositions which Liszt created to demonstrate his own technical prowess that it is easy to lose sight of the other side of his cre- ative genius. Both as a composer and as an author, Liszt re- iterated his belief in the fundamental kinship of music and the other arts. The visual arts of painting and sculpture were included, but he considered the closest relationship to be with literature, and especially with poetry. -

Dubrovački Simfonijski Orkestar Dubrovnik Symphony Orchestra

72. DUBROVAČKE LJETNE IGRE 72ND DUBROVNIK SUMMER FESTIVAL 2021. HRVATSKA CROATIA DUBROVAČKI SIMFONIJSKI ORKESTAR DUBROVNIK SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA EDUARDO STRAUSSER dirigent Conductor GORAN FILIPEC glasovir piano ISPRED KATEDRALE IN FRONT OF CATHEDRAL 18. KOLOVOZA 2021. | 18 AUGUST 2021 21:30 9.30 PM FRANZ LISZT: TOTENTANZ / PLES MRTVACA / DANCE OF DEATH, FANTAZIJA ZA KLAVIR I ORKESTAR / FANTASY FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA, S. 126I ROBERT SCHUMANN: SIMFONIJA U C-DURU BR. 2, OP. 61 / SYMPHONY NO. 2 IN C MAJOR, OP. 61 SOSTENUTO ASSAI. ALLEGRO MA NON TROPPO SCHERZO. ALLEGRO VIVACE ADAGIO ESPRESSIVO ALLEGRO MOLTO VIVACE FRANZ LISZT / FERRUCCIO BUSONI: RHAPSODIE ESPAGNOLE / ŠPANJOLSKA RAPSODIJA / SPANISH RHAPSODY, BV B 58 (S. 254) Franz Liszt (Rajnof, 1811. – Bayreuth, (iako je inače objavljivao detalje o djelima). 1886.), skladatelj i jedan od najvažnijih Klavirski solist na praizvedbi 1865. bio je pijanista svojega doba, učio je glazbu u Hans von Bülow. Mađarskoj od oca, u Beču od Czernyja i Efektno djelo koje, očekivano, traži veliku Salierija, a u Parizu je svirao po salonima te virtuoznost solista, postoji u inačici za učio na privatnim satovima. Na mladog klavir i dvjema inačicama za klavir i Liszta, kao i na Schumanna, snažan je orkestar (nastalima nakon brojnih Lisztovih dojam ostavio Paganini, čiju je virtuoznost preinaka). Druga, razrađenija inačica češće Liszt želio prenijeti na klavirsku glazbu. se izvodi, a DSO i Goran Filipec izvest će Živio je u Ženevi, u Parizu, u Weimaru, prvu, koju je 1919. izdao Ferruccio Busoni poslije je često odlazio u domovinu – autor obrade drugog Lisztova djela na Mađarsku, kojom se oduševljavao, a i ona ovom programu. -

A Survey of Orchestral Excerpt Books for the Flutist Sarah Jane Young

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2015 A Survey of Orchestral Excerpt Books for the Flutist Sarah Jane Young Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A SURVEY OF ORCHESTRAL EXCERPT BOOKS FOR THE FLUTIST By SARAH JANE YOUNG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2015 Sarah Jane Young submitted this treatise on March 25, 2015. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eva Amsler Professor Directing Treatise Alice-Ann Darrow University Representative Eric Ohlsson Committee Member Alexander Jiménez Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I dedicate this treatise in loving memory of my grandparents, Helen H. and Robert W. Starke. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Darrow, Dr. Jiménez, and Dr. Ohlsson for their support and wisdom. I am very grateful for my parents Jane and Richard Young, and my grandparents Janet and Gordon Young, for encouraging me. I am indebted to Ellen Mosley, Dean Pieskee, Justin Page, and Andrew Young for their assistance editing this document. I am especially grateful for my teacher Eva Amsler for all of her dedication and support. iv TABLE -

Concert: Liszt Festival II - the Dualities of Liszt Mallory Bernstein

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-9-2011 Concert: Liszt Festival II - The Dualities of Liszt Mallory Bernstein Kawai Chan Peter Cirka Angela DiIorio Joshua Horsch See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bernstein, Mallory; Chan, Kawai; Cirka, Peter; DiIorio, Angela; Horsch, Joshua; Sender, Shelby; Weismann, Allison; and Welsh, Sam, "Concert: Liszt Festival II - The Dualities of Liszt" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 271. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/271 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Authors Mallory Bernstein, Kawai Chan, Peter Cirka, Angela DiIorio, Joshua Horsch, Shelby Sender, Allison Weismann, and Sam Welsh This program is available at Digital Commons @ IC: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/271 Liszt Festival II The Dualities of Liszt Franz Liszt: Saint or Sinner? Hockett Family Recital Hall Sunday, October 9, 2011 1:00 p.m. Alumni Recital from Years of Pilgrimage - 1st Year: Switzerland, Franz Liszt S160 (1848-54) (1811-1886) No. 6 Vallée d'Obermann Angela DiIorio BM '09, piano from Years of Pilgrimage - 1st Year: Switzerland, Franz Liszt S160 (1848-54) No. 9 Les cloches de Genève from Years of Pilgrimage - 2nd Year: Italy, S161 (1837-49) No. 1 Sposalizio Peter Cirka BM '06, piano from Poetic and Religious Harmonies, Franz Liszt S173 (1845-52) No. -

Franz Liszt (1811—1886)

Simply Charlotte Mason presents usic tudy M with tShe Masters liszt “Let the young people hear good music as often as possible, . let them study occasionally the works of a single great master until they have received some of his teaching, and know his style.” —Charlotte Mason With Music Study with the Masters you have everything you need to teach music appreciation successfully. Just a few minutes once a week and the simple guidance in this book will infuence and enrich your children more than you can imagine. In this book you will fnd • Step-by-step instructions for doing music study with the included audio recordings. • Listen and Learn ideas that will add to your understanding of the music. • A Day in the Life biography of the composer that the whole family will enjoy. • An additional longer biography for older students to read on their own. • Extra recommended books, DVDs, and CDs that you can use to learn more about the composer and his works. Simply Charlotte Maso.comn Music Study with the Masters Franz Liszt (1811—1886) by Emily Lin and Sonya Shafer Music Study with the Masters: Franz Liszt © 2019, Simply Charlotte Mason All rights reserved. However, we grant permission to make printed copies or use this work on multiple electronic devices for members of your immediate household. Quantity discounts are available for classroom and co-op use. Please contact us for details. Cover Design: John Shafer ISBN 978-1-61634-445-0 printed ISBN 978-1-61634-446-7 electronic download Published by Simply Charlotte Mason, LLC 930 New Hope Road #11-892 Lawrenceville, Georgia 30045 simplycharlottemason.com Printed by PrintLogic, Inc.