The Chinese Cultural Perceptions of Innovation, Fair Use, and the Public Domain: a Grass-Roots Approach to Studying the U.S.-China Copyright Disputes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatiotemporal Changes and the Driving Forces of Sloping Farmland Areas in the Sichuan Region

sustainability Article Spatiotemporal Changes and the Driving Forces of Sloping Farmland Areas in the Sichuan Region Meijia Xiao 1 , Qingwen Zhang 1,*, Liqin Qu 2, Hafiz Athar Hussain 1 , Yuequn Dong 1 and Li Zheng 1 1 Agricultural Clean Watershed Research Group, Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Key Laboratory of Agro-Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] (M.X.); [email protected] (H.A.H.); [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (L.Z.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Simulation and Regulation of Water Cycle in River Basin, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100048, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-82106031 Received: 12 December 2018; Accepted: 31 January 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: Sloping farmland is an essential type of the farmland resource in China. In the Sichuan province, livelihood security and social development are particularly sensitive to changes in the sloping farmland, due to the region’s large portion of hilly territory and its over-dense population. In this study, we focused on spatiotemporal change of the sloping farmland and its driving forces in the Sichuan province. Sloping farmland areas were extracted from geographic data from digital elevation model (DEM) and land use maps, and the driving forces of the spatiotemporal change were analyzed using a principal component analysis (PCA). The results indicated that, from 2000 to 2015, sloping farmland decreased by 3263 km2 in the Sichuan province. The area of gently sloping farmland (<10◦) decreased dramatically by 1467 km2, especially in the capital city, Chengdu, and its surrounding areas. -

Exploring Counterfactuals in English and Chinese. Zhaoyi Wu University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1989 Exploring counterfactuals in English and Chinese. Zhaoyi Wu University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Wu, Zhaoyi, "Exploring counterfactuals in English and Chinese." (1989). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4511. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING COUNTERFACTUALS IN ENGLISH AND CHINESE A Dissertation Presented by ZHAOYI WU Submitted to the Graduate Schoo 1 of the University of Massachusetts in parti al fulfillment of the requirements for the deg ree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February, 1989 School of Education © Copyright by Zhaoyi Wu 1989 All Rights Reserved exploring counterfactuals IN ENGLISH AND CHINESE A Dissertation Presented by ZHAOYI WU Approved as to style and content by: S' s\ Je#£i Willett^ Chairperson oT Committee Luis Fuentes, Member Alfred B. Hudson, Member /V) (it/uMjf > .—A-- ^ ' 7)_ Mapdlyn Baring-Hidote, Dean School of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the help and suggestions given by professors of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and the active participation of Chinese students in the discussion of counterfactuals in English and Chinese. I am grateful to Dr. Jerri Willett for her recommendation of references to various sources of literature and her valuable comments on the manuscript. -

Gutenberg Publishes the World's First Printed Book

Gutenberg Publishes the World's First Printed Book The exact date that Johannes Gutenberg published his first book - The Bible - isn't clear, although some historians believe the first section was published on September 30, 1452. The completed book - according to the Library of Congress - may have been released around 1455 or 1456. What is for sure is that Gutenberg's work, published on his printing press, changed the world. For the first time, books could be "mass produced" instead of "hand copied." It is believed that 48 originals, in various states of repair, still exist. The British Library has two copies - one printed on paper, the other on vellum (from the French word Vélin, meaning calf's skin) - and they can be viewed and compared online. The Bible, as Gutenberg published it, had 42 lines of text, evenly spaced in two columns: Gutenberg's Bible was a marvel of technology and a beautiful work of art. It was truly a masterpiece. The letters were perfectly formed, not fuzzy or smudged. They were all the same height and stood tall and straight on the page. The 42 lines of text were spaced evenly in two perfect columns. The large versals were bright, colorful and artistic. Some pages had more colorful artwork weaving around the two columns of text. (Johannes Gutenberg: Inventor of the Printing Press, by Fran Rees, page 67.) Did Gutenberg know how important his work would become? Most historians think not: Gutenberg must have been pleased with his handiwork. But he wouldn't have known then that this Bible would be considered one of the most beautiful books ever printed. -

Introduction to Neijing Classical Acupuncture Part II: Clinical Theory Journal of Chinese Medicine • Number 102 • June 2013

20 Introduction to Neijing Classical Acupuncture Part II: Clinical Theory Journal of Chinese Medicine • Number 102 • June 2013 Introduction to Neijing Classical Acupuncture Part II: Clinical Theory Abstract By: Edward Neal As outlined in Part I of this article, the theories and practices of Neijing classical acupuncture are radically different from the type of acupuncture commonly practised today. In essence, Neijing classical acupuncture is Keywords: a form of clinical surgery, the goal of which is to restore the body’s circulatory pathways and tissue planes to a Acupuncture, state of dynamic balance. In its clinical application, Neijing classical acupuncture is a physician-level skill built Neijing, classical, upon a sophisticated understanding of the innate patterns of nature and an in-depth knowledge of the structure history, basic and physiology of the human body. Neijing classical acupuncture does not depend on point-action theory - the principles conceptual framework that dominates most current thinking in modern acupuncture - for its therapeutic efficacy. Rather, the goal of Neijing classical acupuncture is to regulate the different tissue planes of the body in order to restore the free circulation of blood, and in doing so allow the body to return to its original state of balance and innate self-healing. I. Background theoretical descriptions of acupuncture were outlined The detailed writings laid down in the original texts in the original medical texts where their core principles of Chinese medicine during the later Warring States period (475-221 BCE) and Western Han Dynasty (206 that is the least understood today.3 BCE-9 CE) represent a comprehensive theoretical system that has stood the test of time for over two History of the Lingshu family of texts millennia. -

Chinese Inventions - Paper & Movable Type Printing by Vickie

Name Date Chinese Inventions - Paper & Movable Type Printing By Vickie Invention is an interesting thing. Sometimes, an invention was developed to fulfill a specific need. Other times, it was simply a chance discovery. Looking back in history, there are two Chinese inventions that fell into the first category. They are paper and movable type printing. Long before paper was invented, the ancient Chinese carved characters to record their thoughts on tortoise shells, animal bones, and stones. Since those "writing boards" were heavy and not easy to carry around, they switched to writing on bamboo, wooden strips, and silk. The new alternatives were clearly better, but they were either still heavy or very costly. Then, during the Western Han dynasty (202 B.C. - 8 A.D.), paper made its debut. Its inventor is unknown. When paper first came out, it was not easy to produce in large quantities. And its quality was poor. Several decades later, a palace official named Tsai Lun (also spelled as Cai Lun) had a breakthrough in the papermaking process. He experimented with different materials and eventually settled on using tree bark, rags, and bits of rope to produce paper. He presented his first batch of paper to the emperor of the Eastern Han dynasty in 105 A.D. Tsai Lun's technique of making paper became an instant hit! It was quickly introduced to Korea and other countries nearby. In 751 A.D., Arabs learned the technique from the Chinese soldiers they captured in a war. They passed it on to Europe and, eventually, other parts of the world. -

Four Great Inventions of China Many of the Greatest Inventions in Human History Were First Made in China

History Topic of the Month Four Great Inventions of China Many of the greatest inventions in human history were first made in China. By the 13th century, China was an innovative and exciting place to live. Travellers from Europe discovered things there that were beyond imagination in Europe. When the explorer Marco Polo arrived in China, he encountered a Contributer: © Patrick Guenette / 123rf country vastly different from his home of Venice. In his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, Polo describes cities Cai Lun (AD c.57 – 121), was a Chinese courtier official. He is believed to with broad, straight and clean streets (very different from his be the inventor of paper and the home in Venice) where even the poorest people could wash papermaking process, discovering in great bath houses at least three time a week (again very techniques that created paper as we different from hygiene in Europe). would recognise it today. China celebrates four particular innovations as “the Four Great Inventions” — they were even featured as a part of the opening ceremony for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. So, what were these four great inventions? Writing it all down: Paper The first of the great inventions was something we all use almost every day: paper. Many different materials had been used for writing things down, like bamboo, wood (both hard to store and write on) or silk and cloth (much more expensive). Types of paper have been found in archaeological records dating back thousands of years, but it was very difficult to make. It wasn’t until AD c.105 that a quick and easy way of making paper was invented. -

Spatial Association and Effect Evaluation of CO2 Emission in the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration: Quantitative Evidence from Social Network Analysis

sustainability Article Spatial Association and Effect Evaluation of CO2 Emission in the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration: Quantitative Evidence from Social Network Analysis Jinzhao Song 1, Qing Feng 1, Xiaoping Wang 1,*, Hanliang Fu 1 , Wei Jiang 2 and Baiyu Chen 3 1 School of Management, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an 710055, China; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (Q.F.); [email protected] (H.F.) 2 Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Pennsylvania State University, Forest Resources Building, University Park, PA 16802, USA; [email protected] 3 College of Engineering, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 October 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018; Published: 20 December 2018 Abstract: Urban agglomeration, an established urban spatial pattern, contributes to the spatial association and dependence of city-level CO2 emission distribution while boosting regional economic growth. Exploring this spatial association and dependence is conducive to the implementation of effective and coordinated policies for regional level CO2 reduction. This study calculated CO2 emissions from 2005–2016 in the Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration with the IPAT model, and empirically explored the spatial structure pattern and association effect of CO2 across the area leveraged by the social network analysis. The findings revealed the following: (1) The spatial structure of CO2 emission in -

UC GAIA Chen Schaberg CS5.5-Text.Indd

Idle Talk New PersPectives oN chiNese culture aNd society A series sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies and made possible through a grant from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange 1. Joan Judge and Hu Ying, eds., Beyond Exemplar Tales: Women’s Biography in Chinese History 2. David A. Palmer and Xun Liu, eds., Daoism in the Twentieth Century: Between Eternity and Modernity 3. Joshua A. Fogel, ed., The Role of Japan in Modern Chinese Art 4. Thomas S. Mullaney, James Leibold, Stéphane Gros, and Eric Vanden Bussche, eds., Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China’s Majority 5. Jack W. Chen and David Schaberg, eds., Idle Talk: Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China Idle Talk Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China edited by Jack w. cheN aNd david schaberg Global, Area, and International Archive University of California Press berkeley los Angeles loNdoN The Global, Area, and International Archive (GAIA) is an initiative of the Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, in partnership with the University of California Press, the California Digital Library, and international research programs across the University of California system. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. -

History of the Book in China Oxford Reference

9/1/2016 40 The History of the Book in China Oxford Reference Oxford Reference The Oxford Companion to the Book Edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen Publisher: Oxford University Press Print Publication Date: 2010 Print ISBN13: 9780198606536 Published online: 2010 Current Online Version: 2010 eISBN: 9780199570140 40 The History of the Book in China J. S. EDGREN 1 The book before paper and printing 2 Tang to Yuan (7th–14th centuries) 3 Ming to Qing (14th–19th centuries) 4 The 20th century 1 The book before paper and printing nd th Although the early invention of true paper (2 century BC) and of textual printing (late 7 century) by *woodblock printing profoundly influenced the development of the book in China, the materials and manufacture of books before paper and before printing also left some traces. Preceding the availability of paper as a writing surface, the earliest books in China, known as jiance or jiandu, were written on thin strips of prepared bamboo and wood, which were usually interlaced in sequence by parallel bands of twisted thongs, hemp string, or silk thread. The text was written with a *writing brush and lampblack *ink in vertical columns from right to left—a *layout retained by later MSS and printed books—after which the strips were rolled up to form a primitive *scroll binding (see 17). The surviving specimens of jiance are mostly the result of 20th th rd century scientific archaeological recovery, and date from around the 6 century BC to the 3 century AD. -

Family and Society in Tang and Song Dynasties- Invention, Artistic Creativity, and Scholarly Refinement

Family and Society in Tang and Song Dynasties- Invention, Artistic Creativity, and Scholarly Refinement Hannah Boisvert and Malik Power Family Society Family structure in the Tang and Song dynasty was very similar to the family structures found in earlier time periods. Main aspects of families in the Tang and Song period • Improvement in role of women • Respect and importance of males and elders • Marriage alliances • Gender gap present • Divorce • Male dominance Role of Men and Women As seen in previous areas, men were still perceived as superior to women. Some examples of this include the following: • Authority- Males held the power in family societies. • Women’s responsibilities in the home were set by neo-Confucian thinking. • There was a major difference between the treatment of men and women. • The position of women began to slowly improve. • Marriage alliances began forming. • Divorce became an option. • Footbinding displayed the constriction women faced. Children and Importance of Elders • Like men, elders held a role of authority in families. • Children were expected to obey men and elders as well. There was severe punishment for hitting parents, grandparents, and siblings. • Marriages were almost always arranged for children, especially in the Tang dynasty. Invention • Although there were considerable political transformations, the Tang and Song eras are thought of as a time of remarkable Chinese accomplishments, in science, technology, literature, and the fine arts. • Other civilizations were also affected by the spread of these new tools, production techniques, and weapons. These tools helped change human development. Inventions in Agriculture Many new innovations had appeared in agriculture during the Tang and Song dynasty. -

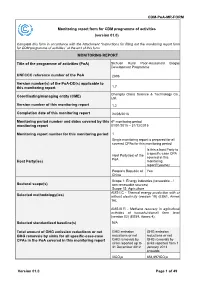

Monitoring Report Form for CDM Programme of Activities (Version 01.0)

CDM-PoA-MR-FORM Monitoring report form for CDM programme of activities (version 01.0) Complete this form in accordance with the Attachment “Instructions for filling out the monitoring report form for CDM programme of activities” at the end of this form. MONITORING REPORT Title of the programme of activities (PoA) Sichuan Rural Poor-Household Biogas Development Programme UNFCCC reference number of the PoA 2898 Version number(s) of the PoA-DD(s) applicable to this monitoring report 1.7 Chengdu Oasis Science & Technology Co., Coordinating/managing entity (CME) Ltd. Version number of this monitoring report 1.2 Completion date of this monitoring report 24/08/2016 Monitoring period number and dates covered by this 4th monitoring period monitoring report 01/01/2015 – 31/12/2015 Monitoring report number for this monitoring period 1 Single monitoring report is prepared for all covered CPAs for this monitoring period Is this a host Party to a specific-case CPA Host Party(ies) of the covered in this PoA Host Party(ies) monitoring report?(yes/no) People’s Republic of Yes China Scope 1: Energy industries (renewable - / Sectoral scope(s) non-renewable sources) Scope 15: Agriculture AMS-I.C - Thermal energy production with or Selected methodology(ies) without electricity (version 19) (EB61, Annex 16); AMS-III.R - Methane recovery in agricultural activities at household/small farm level (version 02) (EB59, Annex 4). Selected standardized baseline(s) N/A Total amount of GHG emission reductions or net GHG emission GHG emission GHG removals by sinks for all specific-case-case reductions or net reductions or net CPAs in the PoA covered in this monitoring report GHG removals by GHG removals by sinks reported up to sinks reported from 1 31 December 2012 January 2013 onwards 0tCO2e 854,697tCO2e Version 01.0 Page 1 of 49 CDM-PoA-MR-FORM PART I - Programme of activities SECTION A. -

The Hundred Surnames: a Pinyin Index

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 12:59 Page 3 The hundred surnames: a Pinyin index Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Ai Ai Ai Zidong Cong Ts’ung Zong Cong Zhen Ai Ai Ai Songgu Cui Ts’ui Cui Jian, Cui Yanhui An An An Lushan Da Ta Da Zhongguang Ao Ao Ao Taosun, Ao Jigong Dai Tai Dai De, Dai Zhen Ba Pa Ba Su Dang Tang Dang Jin, Dang Huaiying Bai Pai Bai Juyi, Bai Yunqian Deng Teng Tang, Deng Xiaoping, Bai Pai Bai Qian, Bai Ziting Thien Deng Shiru Baili Paili Baili Song Di Ti Di Xi Ban Pan Ban Gu, Ban Chao Diao Tiao Diao Baoming, Bao Pao Bao Zheng, Bao Shichen Diao Daigao Bao Pao Bao Jingyan, Bao Zhao Ding Ting Ding Yunpeng, Ding Qian Bao Pao Bao Xian Diwu Tiwu Diwu Tai, Diwu Juren Bei Pei Bei Yiyuan, Bei Qiong Dong Tung Dong Lianghui Ben Pen Ben Sheng Dong Tung Dong Zhongshu, Bi Pi Bi Sheng, Bi Ruan, Bi Zhu Dong Jianhua Bian Pien Bian Hua, Bian Wenyu Dongfang Tungfang Dongfang Shuo Bian Pien Bian Gong Dongguo Tungkuo Dongguo Yannian Bie Pieh Bie Zhijie Dongmen Tungmen Dongmen Guifu Bing Ping Bing Yu, Bing Yuan Dou Tou Dou Tao Bo Po Bo Lin Dou Tou Dou Wei, Dou Mo, Bo Po Bo Yu, Bo Shaozhi Dou Xian Bu Pu Bu Tianzhang, Bu Shang Du Tu Du Shi, Du Fu, Du Mu Bu Pu Bu Liang Du Tu Du Yu Cai Ts’ai Chai, Cai Lun, Cai Wenji, Cai Ze Du Tu Du Xia Chua, Du Tu Du Qiong Choy Duan Tuan Duan Yucai Cang Ts’ang Cang Xie Duangan Tuankan Duangan Tong Cao Ts’ao Tso, Tow Cao Cao, Cao Xueqin, Duanmu Tuanmu Duanmu Guohu Cao Kun E O E