Evangelicals and Democracy, Around the World and Across Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martyrdom Situation Sources, 2000-2010 General Works Allen, Jr

Martyrdom situation sources, 2000-2010 General works Allen, Jr., John, The Global War on Christians: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Anti- Christian Persecution (New York: Image, 2013). Marshall, Paul, Lela Gilbert, and Nina Shea, Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2013). Forum 18 website (www.forum18.org) Voice of the Martyrs website (www.persecution.com) Open Doors website (www.opendoors.org) Christian Persecution info (www.christianpersecution.info) Christian Solidarity International (http://csi-usa.org/persecutiontable.html) Afghanistan Persecuted, p. 205-213 • Death of Abdul Latif, convert, by Taliban • July 1, 15, 23, 28; August 7, 2004: deaths of five Afghan converts by Taliban • July 19, 2007: kidnapping of 23 South Korean Christians and death of two by Taliban • August 2010: Taliban kills 10 members of Christian medical team (Assistance Mission) Global War, p. 117-120 • October 2008: Gayle Williams shot to death on her way to work because she had been working for an organization accused of preaching Christianity China Persecuted, p. 25-38 • No explicit martyrdom Eric Leijenaar, “Report: 3000 Chinese Christians ‘Killed’ Since 2000,” BosNewsLife, 3 September 2007, https://chinaview.wordpress.com/2007/09/04/report-3000- chinese-christians-killed-since-2000/ • Figure comes from German-based Society for Threatened Peoples DR Congo International Rescue Committee report Jason Stearns, Dancing in the Glory of Monsters “DR Congo-Rwanda-Uganda: UN Report on War Crimes,” Africa Research Bulletin, 47, no. 9 (2010): 18536A–18537A • Rwanda troops might have committed genocide in DR Congo in 1997 • Human rights violations in DR Congo from 1993 to 2003 “DR Congo – ICC: War Crimes Acquittal,” Africa Research Bulletin, 49, no. -

VOM Canada's Ministry Funds

2020 VOM Canada’s Ministry Funds A LIST OF MINISTRY FUNDS AND THEIR DESCRIPTIONS THE VOICE OF THE MARTYRS INC. | P.O. Box 608, Streetsville, Mississauga, ON L5M 2C1 Give Them the Tools “Often, after a secret service, Christians were caught and sent to prison. There, Christians wear chains with the gladness with which a bride wears a precious jewel received from her beloved.” - Richard Wurmbrand, Tortured for Christ Pastor Richard Wurmbrand, founder of The Voice of the Martyrs international, did not intend it to be a rescue mission. He did not envision the liberation of Christians behind the Iron Curtain by bringing them to the West where they would be free from persecution. Pastor Wurmbrand understood that the best hope for those living in Communist countries was Jesus Christ, as revealed in God’s Word and proclaimed by His faithful church. Instead, Pastor Wurmbrand implored Christians in the West to fervently pray for their brothers and sisters in chains – challenging them to provide tools to persecuted Christians, so they could fulfill the work of the church in these restrictive nations. Such giving needed to be an act of love, bathed in prayer; for as surely as these tools would be used, persecution would increase. The price was high, but many unwavering Christians were willing to pay that price for deploying the Gospel to counteract the hollow and deceptive philosophies that held many of their fellow citizens captive. The strategy of The Voice of the Martyrs has not changed, although the scope of our international ministry has grown immensely. Today, while Bibles remain in high demand, there is a plethora of opportunities to help persecuted Christians stand and endure the fires of persecution, as well as advance the Gospel of Jesus Christ. -

The Annunciator

The Annunciator Newsletter of The Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary 289 Spencer Street, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1Y 2R1 (613) 722-9139 Vol. 10 No. 8 www.cathedraloftheannunciation.org June 2008 In Part 2 of his Papal Infallibility article inside this issue, Dr. Henry doesn’t hazard a guess at how many Protestant denominations there are in the world today. The last number that I remember reading some 15 years ago was a staggering 40,000! Dr. Henry does allude to the lack of any collegial and well-informed authority that has characterized the post-Reformation churches by the time the nineteenth century arrived as a factor for this mind- boggling proliferation. Of course, each of these new denominations was spawned by someone who felt that their novel interpretation of Scripture was, well, infallible; and, therefore, the world absolutely needed yet another (sometimes historically ignorant, and often intellectually dishonest) ecclesial body. Dr. Henry alludes to this highly ironic situation: Protestant groups will only use the word “infallible” when criticizing papal infallibility – which, by its very nature of being bound up with significant checks and balances, is gathering very much dust without having been used more than a few times – while on the other hand, exercising what can sometimes be characterized as an almost totalitarian infallibility on their faithful. Archbishop Hepworth referred to “40,000 Protestant popes” within this context of authority. In fact, in its extreme instance, the concept of “sola Scriptura” (Scripture only), where individuals are encouraged to make up their own interpretation of the Bible, everyone is potentially an infallible interpreter of God’s word. -

Bulletin for Aug. 1

Welcome to Marysville Berean Church SUNDAY SERVANTS: August 1, 2021 Nursery workers today: Eric and Sylvia Aug. 8: Bobby and Wendy “Poverty in Disobedience” Children’s church workers today: Proverbs 11:23-28 rd Kdg.-3 : Ellie and Mona Sunday school classes are offered for all ages. Adult 4-5 yr. olds: Susan and Brandi classes are: Children’s church workers For Aug. 8: “We Will Not Be Silenced” class in the sanctuary taught by Don Kdg.-3rd: Jolene and Jonas Fincham. 4-5 yr. olds: Brenda and Dominic Bible Basics, taught by Pastor Joel, will not meet this morning. Cleaning For Aug. 8: Sharon ReFreshments For Aug. 8: Pam, Marabeth, Rubiel, Sylvia, Regina Today’s Events 4:00 p.m. – Jail Ministry Coming Events 5:30 p.m. – Kid’s Night Out at Lions Park – Wacky Water Night “Kid’s Night Out” – August 8 at the church (Movie Night) This Week’s Events On August 15, Robbie Nutter, director of Christian Challenge at Kansas Men’s Prayer Meeting – Thursday at 7:30 p.m. State University, will deliver the message. Please stay for Sunday Announcements school to hear a panel discussion on mentoring/discipleship. We welcome Scott Mathis’ son-in-law, Jared Lee, to our ser- Bridal Shower for Beth Hawkins – August 22 at 6 p.m. at the home of vice this morning. He will be bringing the message. Jared Regina Breshears, 920 N. 15th St., Marysville. Beth and Ben are regis- and his wife, Courtney, live in Lincoln with their two chil- tered at Walmart, Menards, and Amazon. -

Hearts of Fire Chapter 1

hearts of fire_fm.qxp 3/22/2019 1:47 PM Page i VOM BOOKS hearts of fire_fm.qxp 3/22/2019 1:47 PM Page ii Copyright © 2003, 2015 The Voice of the Martyrs. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotation in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by VOM Books, 1815 SE Bison Rd., Bartlesville, OK 74006 Previously published by Thomas Nelson (ISBN 978-0-8499-4422-2) Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations used in this book are from the New King James Version (nkjv), copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982, Thomas Nelson, Publishers. Other Scripture references are from the King James Version of the Bible (kjv). “Because He Lives” Words by William J. and Gloria Gaither. Music by William J. Gaither. Copyright © 1971 William J. Gaither, Inc. All rights controlled by Gaither Copyright Management. Used by permission. Many of the names and places in this book’s testimonies have been changed to protect the identities of those represented. It was also neces- sary to omit details concerning ministry activities that continue within these nations to protect the lives of those involved. Some court transcripts and other quoted materials have been edited for brevity and clarity. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearts of Fire / by The Voice of the Martyrs. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-88264-150-8 (softcover) 1. Christian women—Developing countries—Biography. 2. -

Budapest Report on Christian Persecution 2019

BUDAPEST REPORT ON CHRISTIAN PERSECUTION 2019 BUDAPEST REPORT ON CHRISTIAN PERSECUTION 2019 Edited by JÓZSEF KALÓ, FERENC PETRUSKA, LÓRÁND UJHÁZI HÁTTÉR KIADÓ Sponsor PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE Authors Tristan Azbej Ferenc Petruska Ekwunife Basil Byrappa Ramachandra Antal Birkás István Resperger Gábor Csizmazia Gergely Salát Vilmos Fischl Klára Siposné Kecskeméthy Péter Forisek Eszter Petronella Soós János Frivaldszky Péter Tarcsay József Kaló Muller Thomas András Kóré Zsigmond Tömösváry Viktor Marsai Lóránd Ujházi József Padányi Péter Wagner Pampaloni Massimo Péter Krisztián Zachar Csongor Párkányi Péter Zelei ISBN 978 615 5124 67 9 The ideas and opinions contained in the present book do not necessarily represent the position of the Hungarian Government. The responsibility for the informations of this volume belongs exclusively to the authors and editors. © The Editors, 2019 © The Authors, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical metholds, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. CONTENTS Welcoming thonghts of Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary ........................................................... 7 The dedication of Cardinal Péter Erdő, the Archbishop of Esztergom–Budapest ..................................... 9 Foreword of Brigadier -

“The Two Witnesses” Revelation 11:1-14 May 2, 2021 This Particular

Screen 1 Screen 2 “The Two Witnesses” Revelation 11:1-14 May 2, 2021 This particular vision has long been one of the most difficult passages (if not the most complicated in the whole book) in the Revelation. There are at minimum five different broad interpretations of these views. Nevertheless, the possibility for a satisfactory interpretation of the section is not hopeless. PRAY for understanding and application. Revelation 11:1 “Then I was given a measuring rod like a staff, and I was told, Screen 3 ‘Rise and measure the temple of God and the altar and those who worship there.’” The measuring rod in Ezekiel 40:5 was about ten feet long. The “temple” always refers to the literal temple in Jerusalem in all of the gospels and John’s writings except in John 2:19-21 where it refers to the body of Jesus. As a good Baptist, raised/taught the premillennial dispensationalist view of the Revelation, I am always going to lean in the direction of the literal – in all of Scriptures and in the Apocalypse, too. Chapters 10 and 11 of Revelation are to be taken together as a unit, describing the fate of the 144,000 sealed believers (a.k.a. the church) on earth during the Great Tribulation period of time just before Christ’s return (second coming). Here, in Chapter 11, John’s role of a passive spectator has given way to active involvement in his own vision (just as in Chapter 10 from last week). Here, he is given a “measuring rod” – the measuring of the temple (in Jerusalem, again, one day) is a way of declaring its preservation. -

When Faith Is Forbidden, Chapters

DAY 1 The heart of man plans his way, but the LORD establishes his steps. PROVERBS 16:9 Yei, Sudan, 1998 It’s not unusual, your first day overseas, to be wide awake at 2:30 or 3:00 in the morning. I’ve heard lots of theories about how jetlag can be beaten, but so far I don’t find any that actually work. Jetlag just keeps beating me. During the day, get as much sunlight as you can. Other than that, you just have to fight through it. Our team wasn’t supposed to go to Yei first during our time in Sudan. But the first lesson of travel is that, sometimes, things don’t go according to plan. Our goal was to go to Turalei. It was in Ayien, a village near Turalei, that Pastor Abraham Yac Deng had led a church of four hundred Sudanese Christians—with his small red pocket Bible, the only copy of the Scriptures in the en- WFIF_INT_F.indd 17 11/2/20 10:13 AM WHEN FAITH IS FORBIDDEN tire congregation. Abraham had been thrilled when a previous VOM team brought boxes and boxes of Bibles to Turalei. The thought that every family in his church could have their own copy of the Bible was almost too amazing to consider. A member of the VOM team asked Abraham what his favorite verse was, and he quoted Romans 6:23: “For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” Four days after that conversation with Abraham and those Bi- bles being delivered, radical Islamic mujahidin attacked Ayien. -

537E34d0223af4.56648604.Pdf

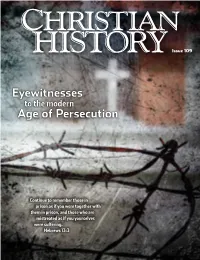

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 109 Eyewitnesses to the modern Age of Persecution Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering. Hebrews 13:3 RARY B I L RT A AN M HE BRIDGE T COTLAND / S RARY, B I L RARY B NIVERSITY I U L RT A AN LASGOW M G “I hAD TO ASK FOR GRACe” Above: Festo Kivengere challenged Idi Amin’s killing of Ugandan HE BRIDGE Christians. T BOETHIUS BEHIND BARS Left: The 6th-c. Christian ATALLAH / M I scholar was jailed, then executed, by King Theodoric, N . CHOOL (14TH CENTURY) / © G an Arian. S RARY / B TALIAN I I L ), Did you know? But soon she went into early labor. As she groaned M in pain, servants asked how she would endure mar- CHRISTIANS HAVE SUFFERED FOR tyrdom if she could hardly bear the pain of childbirth. , 1385 (VELLU She answered, “Now it is I who suffer. Then there will GOSTINI PICTURE A THEIR FAITH THROUGHOUT HISTORY. E be another in me, who will suffer for me, because I am D HERE ARE SOME OF THEIR STORIES. also about to suffer for him.” An unnamed Christian UM COMMENTO woman took in her newborn daughter. Felicitas and C SERVING CHRIST UNTIL THE END her companions were martyred together in the arena Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, is one of the earliest mar- in March 202. TALY, 16TH CENTURY / I tyrs about whom we have an eyewitness account. In HILOSOPHIAE P E, M the second century, his church in Smyrna fell under IMPRISONED FOR ORTHODOXY O great persecution. -

Prayer for the Persecuted Church 11 Places Where Persecuted Christians Need Our Prayers

Prayer for the Persecuted Church 11 Places Where Persecuted Christians Need Our Prayers Over 245 million Christians live in the 50 countries ranked on the World Watch List as worst for Christians. Between November 2017 and October 2018, 4,136 Christians were killed for their faith in these countries, over 1,266 churches or Christian buildings were attacked, and 2,625 believers were detained, arrested, sentenced, or imprisoned — many of them without a trial. Voice of the Martyrs, Open Doors, International Christian Concern, and other organizations have provided information, prayers, and an app to help believers pray for and connect with the persecuted church for the days of prayer held each year in November. New in 2019, Open Doors has recorded videos of 20 evangelical leaders praying for Christians around the world (a couple appear in the list below). Todd Nettleton, host of Voice of the Martyrs’ VOM Radio, said Christians can head the exhortation of Hebrews 13:3 and “remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison.” For those suffering due to their faith, “this is a significant encouragement to the persecuted parts of our family because they know they are being prayed for.” Choose a country and then pray for the persecuted believers in that country (using the prayer list at the end of this document. 1. China Christian persecution is not new in China, but under President Xi it is quickly growing, marking a new wave of religious oppression. Chinese authorities are removing young people from church, monitoring worship via CCTV, and prohibiting teachers and medical workers from maintaining any religious affiliation. -

September 14 James: Living out Our Faith

Christ-St. Paul’s Church Fall 2014 Sermon Series Week 1 James: Living Out Our Faith September 14 But be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves. James 1:22 Living Out Our Faith: James 1:1 The epistle of James is commonly believed to have been written by James, the brother of Jesus around AD 55- 60. During this time in church history the “honeymoon” period was over and persecution was beginning. The brother of John had been martyred by Herod, Stephen had been stoned to death and the Jews had been scattered throughout the Roman Empire. Several of the Apostles had begun their missionary journeys and James became one of the leaders of the Church in Jerusalem. From reading the epistle of James we see that James was no doubt a man of great conviction and faith. He was one of the first individuals to whom Christ appeared after his resurrection. In Acts 21:18-19 Paul brings greetings to James from the Gentiles and in Galatians 2:9 Paul calls James a “pillar” of the church. When Peter was delivered from prison, he asks that James be notified (Acts 12:17). However, James wasn’t without controversy. His epistle focuses so much on the practical aspects of living out our faith that Martin Luther devalued James’ work as an “epistle of straw”. Luther believed James’ writing conflicted with Paul’s doctrine of justification by faith apart from works. James writes to point out potential problems as well as sin, much of which will be discussed later in this series. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 16-1274 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States __________ TING XUE, Petitioner, v. JEFFERSON B. SESSIONS III, Respondent. __________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit __________ BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE FOUNDATION FOR MORAL LAW AND THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF EVANGELICAL CHAPLAIN ENDORSERS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER __________ ARTHUR A. SCHULCZ, SR. JOHN EIDSMOE CHAPLAINS’ COUNSEL, PLLC Counsel of Record 21043 Honeycreeper Place FOUNDATION FOR Leesburg VA 20175 MORAL LAW (703) 645-4010 One Dexter Avenue [email protected] Montgomery AL 36104 (334) 262-1245 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 2 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 3 ARGUMENT ................................................................ 5 I. The Court should grant certiorari because the split in the circuits creates uncertainty and disruption in the immigration, naturalization, and asylum process. .................................................... 5 II. The Tenth Circuit erred by considering issues of persecution narrowly rather than looking to the broader policies of the Government of China and its ruling Communist Party. ............................................... 6 III. The Tenth Circuit erred by failing to consider the effect of the Religious