Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Eight

The Economic Rape of America - Chapter Eight HISTORY AND THEORY OF TAX AND STATE You have sown much, and harvested little; you eat, but you never have enough; you drink, but you never have your fill; you clothe yourselves, but no one is warm; and you that earn wages earn wages to put them into a bag with holes. -- Haggai 1, verse 6 "... [W]hen it is no longer worth the producers' while to produce, when they are taxed so highly to keep the politicians and their friends on the public payroll that they themselves no longer have a reasonable chance of success in any economic enterprise, then of course production grinds to a halt... When this happens, when the producers can no longer sustain on their backs the increasing load of the parasites, then the activities of the parasites must stop also, but usually not before they have brought down the entire social structure which the producers' activities have created. When the organism dies, the parasite necessarily dies too, but not until the organism has paid for the presence of the parasite with its life. It is in just this way that the major civilizations of the world have collapsed." -- Professor John Hospers, 1975 The history of taxation is also the history of the rise and fall of civilization. It is the history of economic rape. From the history of taxation we can learn... TAX IN EGYPT, ROME, AND THE MIDDLE EAST Charles Adams wrote a superb book, Fight, Flight and Fraud: The Story of Taxation. It is a comprehensive analysis of the history of taxation in the context of the rise and fall of civilizations. -

BXAO Cat 1971.Pdf

SOUTHWESTERN AT OXFORD Britain in the Renaissance A Course of Studies in the Arts, Literature, History, and Philosophy of Great Britain. July 4 through August 15, 1971, University College, Oxford University. OFFICERS AND TUTORS President John Henry Davis, A.B., University of Kentucky; B.A. and M.A., Oxford University; Ph.D., University of Chicago. Dean Yerger Hunt Clifton, B.A., Duke University; M.A., University of Virginia; Ph.D., Trinity College, Dublin. Tutors George Marshall Apperson, Jr., B.S., Davidson College; B.D., Th.M., Th.D., Union Theological Seminary, Virginia. Mary Ross Burkhart, B.A., University of Virginia; M.A., University of Ten nessee. James William Jobes, B.A., St. John's College, Annapolis; Ph.D., University of Virginia. James Edgar Roper, B.A., Southwestern At Memphis; B.A. and M.A., Oxford University; M.A., Yale University. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY Master Redcliffe-Maud of Bristol, The Right Honorourable John Primatt Redcliffe, Baron, M.A. Dean John Leslie Mackie, M.A. Librarian Peter Charles Bayley, M.A. Chaplain David John Burgess, M.A. Domestic Bursar Vice Admiral Sir Peter William Gretton, M.A. University College is officially a Royal Foundation, and the Sovereign is its Visitor. Its right to this dignity, based on medieval claims that it was founded by King Alfred the Great, has twice been asserted, by King Richard II in 1380 and by the Court of King's Bench in 1726. In fact, the college owes its origin to William of Durham who died in 1249 and bequeathed 310 marks, the income from which was to be employed to maintain 10 or more needy Masters of Arts studying divinity. -

January 1878

-J \ \ _^0 n^;^^ Polite ^^}tttt^ [ Published by Authority. ] This Gazette is published for Police information only, and the Police throughout the Colony are instructed to make themselves thoroughly acquainted with the contents, i M. 8. SMITH, Superintendent of Police. No. 1.] WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 2. [1878. Stealing in Dwellings, from the On the night of the 1st ult., from the residence of James Dearing, Irwin,—one pair white blankets, 3 Person, &c. cotton shirts (dark stripes), one night dress, one On the 25th ult., from the person of James Devine, light print skirt, 9 yards grey alpaca, 3 yards dark while asleep at Beard's boarding house, York,—One linsey, one chest tea, and a quantity of flour, the pro cheque on W.A. Bank for £4^, dated 24th Dec, 1877, perty of James Dearing.—CI. 9. drawn by S. E. Burges, Sen. in favor of Anthony Devine. James McDonald, exp., late 9511, strongly On the 15th ult., from the trousers pocket of John suspected. —CI. 1. Cox, which were hanging on a cart wheel on the On the night of the 26tb nit., from John Bryar-^'s Geraldton and Northampton Eoad,—one shilling in stable, St. George's Terrace, Perth,—1 sack, contain silver. George AUett, free, committed this robbeiy.— C.L 10. ing 40 lbs. of chaff, 62 marked on i ick. Identifiable. —C.I. 2. •- On the night on the 29th ult., from the premises On the 22nd ult., from a tool chesi: at the back of of Mrs. Hillsley, Murray Street, Perth,—3 fowls the Invalid Depot, Fremantle,—1 mason's hammer, (common breed). -

Notes to the Introduction I the Expansion of England

NOTES Abbreviations used in the notes: BDEE British Documents of the End of Empire Cab. Cabinet Office papers C.O. Commonwealth Office JICH journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History Notes to the Introduction 1. J. C. D. Clark, '"The Strange Death of British History?" Reflections on Anglo-American Scholarship', Historical journal, 40: 3 (1997), pp. 787-809 at pp. 803, 809. 2. S. R. Ashton and S. E. Stockwell (eds), British Documents of the End of Empire, series A, vol. I: Imperial Policy and Colonial Practice, 1925-1945, part I: Metro politan Reorganisation, Defence and International Relations, Political Change and Constitutional Reform (London: HMSO, 1996), p. xxxix. Some general state ments were collected, with statements on individual colonies, and submitted to Harold Macmillan, who dismissed them as 'scrappy, obscure and jejune, and totally unsuitable for publication' (ibid., pp. 169-70). 3. Clark,' "The Strange Death of British History"', p. 803. 4. Alfred Cobban, The Nation State and National Self-Determination (London: Fontana, 1969; first issued 1945 ), pp. 305-6. 5. Ibid., p. 306. 6. For a penetrating analysis of English constitutional thinking see William M. Johnston, Commemorations: The Cult of Anniversaries in Europe and the United States Today (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 1991). 7. Elizabeth Mancke, 'Another British America: a Canadian Model for the Early Modern British Empire',]ICH, 25: 1 (January 1997), pp. 1-36, at p. 3. I The Expansion of England 1. R. A. Griffiths, 'This Royal Throne ofKings, this Scept'red Isle': The English Realm and Nation in the later Middle Ages (Swansea, 1983), pp. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

UCLA Historical Journal

Issue of British Recognition of the Confederate States of America 1 The Roebuck Motion and the Issue of British Recognition of the Confederate States of America Lindsay Frederick Braun ^^7 j^ \ ith the secession of the southern states from the Union and the i U I outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, British poHcymak- \^\^ ers and financiers had to contend with the novel diplomatic and economic difficulties of relations with two Americas locked in battle. Faced with an uncertain contest abroad and divided affinities at home, the govern- ment of Lord Palmerston chose to steer a middle course of neutrality. This did not, however, prevent advocates and detractors of both sides from orga- nizing opinion and advancing agendas across the country and even into Parliament. Debate on the situation within the warring states and sugges- tions that Britain might do weU to extend formal diplomatic recognition to the Confederate States of America as a sovereign nation, or to intervene in the conflict, appeared regularly in Parliament during the course of the war. The ill-fated Parliamentary motion towards recognition introduced in sum- mer of 1863 by John Arthur Roebuck, Member of Parliament for Sheffield, was the last of the serious attempts to secure recognition. It was, perhaps, the most telling effort of the entire war period in terms of the European diplo- matic landscape and Europe's relations to events in North America. Between the inception of Roebuck's motion in May 1863 and its with- drawal on 13 July 1863, its sponsor engaged in amateur diplomacy with the French, serious breaches of protocol, and eventually witnessed not only the obloquy of pro-Union and anti-interventionist speakers but also the desertion of other pro-Confederate members of Parliament. -

ED\Vj~RD JESSUP

ED\Vj~RD JESSUP OF WEST FARMS, WESTCHESTER CO., NEW YORK, AND HIS DESCEKDANTS. Bitb an Jfnttoburtion anb an ~ppmbix : THE LATTER CONTAINING RECORDS OF OTHER AMERICAN FAMILIES OF THE NAME, WITH SOME ADDITIONAL MEMORANDA. BY REV. HENRY GRISWOLD JESUP. I set the people after their families. NEHl!MIAH iv. 13. CAMBRIDGE: l!rfbattlp llrfntcb for t)lt Su~ot, BY JOHN WILSON AND SO!i. Copyricht, 188'7, BY lbtv. HENRY Gl!.ISWOLD JESUP. ,_ , Ir - ?· 17r. TO MORRIS K. JESUP, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THE WORK WAS UNDERTAKEN, AND \\.HOSE UNFAILING INTEREST HAS FOLLOWED IT TO . ITS COMPLETION, THIS HISTORY AND RECORD OF THE LIFE AND THE DESCENDANTS OF HIS AMERICAN ANCESTOR PREFACE. HE present work was begun in 1879 at the solicita T tion of MORRIS K. JESUP, EsQ., of New York city, and has been prosecuted during intervals of leisure up to the date of publication, a period of nearly eight years. The amount of time and labor involved can be justly estimated only by those who have been engaged in simi lar undertakings. The materials have been drawn from a great variety of sources, and their collection and arrange ment, the harmonizing of discrepancies, and, in extreme cases, the judicious guessz'ng at probabilities, have in volved more of perplexity than the ordinary reader would suppose. Records of every description, and almost with out number, have been examined either personally or through the officials having them in charge, and in one case as distant as Cape Town in South Africa,- records of families, churches, parishes, towns, counties, in foreign lands as well as in the United States; land records and probate records, cemetery inscriptions, local histories, and general histories, wherever accessible. -

Chapter V Educational Provision in Wales Part

CHAPTER V EDUCATIONAL PROVISION IN WALES PART (i) : SCHOOLS In medieval Wales it was the Church which assumed the greatest responsibility for schooling, bardic schools and possibly the households of the Welsh lords being also centres of learning. The English universities, and to a lesser extent, the continental universities and the inns of court, provided further or higher 1 education for the ablest talents of Wales. In England, by the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, lay involvement in educati4n increased, as the needs of the Crown, the aristocracy and the towns expanded, and this was also faintly apparent in as scattered and 2 rural a society as Wales. The revival of classical learning emphasised anew the educational qualities required of administrators and all useful members of the state and which were also to be expected of gentlemen. At a time of social change, in Wales as in England, education became a 3 means of asserting and of reinforcing social distinctions. Neither the schools nor the universities were particularly suited 4 to the task of preparing young gentlemen. The newer grammar schools tried tEadapt, and there were a few signs that the universities and the inns of court, though still largely institutions of professional instruction, made some concessions towards providing a more general and 5 popular education. The essential conservatism of these places meant 6 that they were not in the van of intellectual progress. Rather, they were places for disseminating received and accepted truths intermixed with north European humanism and religious ideology, giving force to 333. 7 the ideal of wise and moral service and leadership. -

The Jesus College Record 2013

RECOR D 2013 CONTENTS FROM THE EDITOR 3 THE PRINCIPAL’S R EPORT 6 FELLOWS & COLLEGE LECTURERS 12 FELLOWS’ NEWS 20 THE DON FOWLER M EMORIAL LECTURE 2013 26 PRIZES, AWARDS, DOCTORATES & ELECTIONS 27 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF GREAT TITS: AN I NTERVIEW WITH L ORD KREBS 39 INTIMATIONS OF MORTALITY BY NORMAN F RISKNEY 46 TRAVEL AWARDS 47 TRAVEL AWARDS REPORTS 49 SIR FRANCIS M ANSELL: THREE TIMES P RINCIPAL OF JESUS C OLLEGE 55 THE SIRENS’ SONG: REDISCOVERING ANCIENT G REEK MUSIC 61 THE WALL PAINTING IN THE JCR 65 THE DAFFODIL’S VERSION BY DAVID CRAM 68 THE BOOKS OF LORD HERBERT OF CHERBURY 69 THE ACCOMMODATION, CATERING AND CONFERENCES TEAM 72 A YEAR IN THE JCR 75 A YEAR IN THE MCR 76 A YEAR IN DEVELOPMENT 77 A YEAR IN CHAPEL 80 SPORTS REPORTS 82 OLD MEMBERS’ OBITUARIES 88 SELECT PUBLICATIONS 104 HONOURS, AWARDS & QUALIF ICATIONS 112 APPOINTMENTS 115 MARRIAGES & CIVIL PARTNERSHIPS 117 BIRTHS & ADOPTIONS 120 IN MEMORIAM 125 USEFUL INFORMATION 128 MERCHANDISE 134 1 2 FROM THE EDITOR DR ARMAND D’A NGOUR Economy once meant good housekeeping. Then came the political economy, the knowledge economy, and the information economy. Now, it seems, we have the attention economy. The notion, which goes back to the 1990s, is that nowadays people compete for attention as much as for money or knowledge. According to the pundits, attention has become a currency: it has scarcity value and endless attraction. As with money, only the naïve or incapable (or the truly wise) can resist its lure. In the digital age, to be a winner in the attention economy requires constant tweeting, blogging, and updating one’s status on Facebook; a hugely time-consuming business. -

The History of Parliament Trust Review of Activities, 2017-18

The History of Parliament Trust Oral History Project interviewees, clockwise from top: Baroness Helene Hayman, Baroness Ann Taylor, Jackie Ballard, Baroness Janet Fookes. All portraits by Barbara Luckhurst, www.barbaraluckhurstphotography.com © Barabara Luckhurst/History of Parliament Trust Review of Activities, 2017-18 Objectives and activities of the History of Parliament Trust The History of Parliament is a major academic project to create a scholarly reference work describing the members, constituencies and activities of the Parliament of England and the United Kingdom. The volumes either published or in preparation cover the House of Commons from 1386 to 1868 and the House of Lords from 1603 to 1832. They are widely regarded as an unparalleled source for British political, social and local history. The volumes consist of detailed studies of elections and electoral politics in each constituency, and of closely researched accounts of the lives of everyone who was elected to Parliament in the period, together with surveys drawing out the themes and discoveries of the research and adding information on the operation of Parliament as an institution. The History has published 22,136 biographies and 2,831 constituency surveys in twelve sets of volumes (46 volumes in all), containing over 25 million words. They deal with 1386-1421, 1509-1558, 1558-1603, 1604-29, 1660-1690, 1690-1715, 1715-1754, 1754- 1790, 1790-1820 and 1820-32. All of these articles, except those on the House of Lords 1660-1715, are now available on www.historyofparliamentonline.org . The History’s staff of professional historians is currently researching the House of Commons in the periods 1422-1504, 1640-1660, and 1832-1868, and the House of Lords in the periods 1603-60 and 1660-1832. -

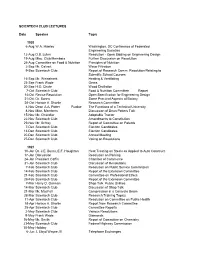

SCIENTECH CLUB LECTURES Date Speaker Topic 1920 6-Aug W.A

SCIENTECH CLUB LECTURES Date Speaker Topic 1920 6-Aug W.A. Hawley Washington, DC Conference of Federated Engineering Societies 12-Aug D.B. Luten Resolution - Open Bidding on Engineering Design 19-Aug Misc. Club Members Further Discussion on Resolution 26-Aug Committee on Food & Nutrition Principles of Nutrition 2-Sep Mr. Calvert Water Filtration 9-Sep Scientech Club Report of Research Comm. Resolution Relating to Scientific School Courses 16-Sep Mr. Weinshank Heating & Ventilating 23-Sep Frank Wade Gems 30-Sep H.O. Chute Wood Distilation 7-Oct Scientech Club Food & Nutrition Committee Report 14-Oct Revise Resolution Open Specification for Engineering Design 21-Oct Dr. Bonns Some Practical Aspects of Botany 28-Oct Horace A. Shonle Research Committee 4-Nov Dean A.A. Potter Purdue The Functions of a Technical University 8-Nov Misc. Members Discussion of Dean Potters Talk 15-Nov Mr. Chandler Adaptable Tractor 22-Nov Scientech Club Amendments to Constitution 29-Nov Mr. Schley Report of Committee on Patents 7-Dec Scientech Club Election Candidates 13-Dec Scientech Club Election Candidates 20-Dec Scientech Club Annual Meeting 27-Dec Scientech Club Voting on Resolutions 1921 10-Jan Dr. J.E. Burns, E.F. Houghton Heat Treating on Steels as Applied to Auto Construct. 17-Jan Discussion Resolution on Parking 24-Jan President Coffin Chamber of Commerce 31-Jan Scientech Club Discussion of Resolutions 7-Feb Scientech Club Resolution on Public Service Commission 14-Feb Scientech Club Report of the Extension Committee 21-Feb Scientech Club Committee on Professional Ethics 28-Feb Scientech Club Report of the Extension Committee 7-Mar Harry O.