TORAH STUDY a Survey of Classic Sources on Timely Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism

eSharp Issue 20: New Horizons A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism Eva van Loenen (University of Southampton) Introduction In this article, I shall examine the history of Hasidic Judaism, a mystical,1 ultra-orthodox2 branch of Judaism, which values joyfully worshipping God’s presence in nature as highly as the strict observance of the laws of Torah3 and Talmud.4 In spite of being understudied, the history of Hasidic Judaism has divided historians until today. Indeed, Hasidic Jewish history is not one monolithic, clear-cut, straightforward chronicle. Rather, each scholar has created his own narrative and each one is as different as its author. While a brief introduction such as this cannot enter into all the myriad divergences and similarities between these stories, what I will attempt to do here is to incorporate and compare an array of different views in order to summarise the history of Hasidism and provide a more objective analysis, which has not yet been undertaken. Furthermore, my historical introduction in Hasidic Judaism will exemplify how mystical branches of mainstream religions might develop and shed light on an under-researched division of Judaism. The main focus of 1 Mystical movements strive for a personal experience of God or of his presence and values intuitive, spiritual insight or revelationary knowledge. The knowledge gained is generally ‘esoteric’ (‘within’ or hidden), leading to the term ‘esotericism’ as opposed to exoteric, based on the external reality which can be attested by anyone. 2 Ultra-orthodox Jews adhere most strictly to Jewish law as the holy word of God, delivered perfectly and completely to Moses on Mount Sinai. -

For Shabbat Morning Prayers. As I Explain On

Here is an abridged Matbeah – service – for Shabbat morning prayers. As I explain on our homepage, while most of this abridged service is designed as if one is davening – praying – alone, I have included the recitation of Mourner’s Kaddish for those who are in mourning or observing Yahrzeit. Ideally, all of us will begin praying at 9:30am on Shabbat morning with a kavannah – intentionality – towards one another. In this way, we will form a community even if we are not standing together in the sanctuary. All of the pages on this outline refer to our Sim Shalom prayer book; however, all of these prayers appear in most traditional prayer books. There is a link to a scanned document with all of the following pages on our homepage. p.10 - Birkot HaShachar p.16-18 - Rabbinic Texts p. 20 - Kaddish D’Rabbanan (for those in mourning or observing Yahrzeit) p.32 - Psalm for Shabbat p. 52 - Mourner’s Kaddish (for those in mourning or observing Yahrzeit) p.54 - Barush She’amar p.72 - Hodu p. 80-82 - Ashrei p. 88 – Halleluyah (Psalm 150) p. 92-94 - Shirat Hayam p. 336-338 - Ha’El B’Tatzumot through Yishtabach (Stop before Hatzi Kaddish) p. 340-352 - Shema and its surrounding prayers before and after p. 354-364 - Silent Amidah (without Kedushah, insert Atah Kadosh paragraph instead) ** Skip the Torah Service ** p. 415 - Prayer for Our Country p. 416 - Prayer for the State of Israel p. 430-440 - Silent Musaf Amidah (without Kedushah, insert Atah Kadosh paragraph instead) p. 510 - Aleinu After this service, I then encourage you to open up a Chumash or some printed version of the Torah reading for the week and read it in Hebrew or English. -

Application for Admission Yeshivas Ohr Yechezkel 2020-2021 Mesivta Ateres Tzvi the Wisconsin Institute for Torah Study 3288 N

APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION YESHIVAS OHR YECHEZKEL 2020-2021 MESIVTA ATERES TZVI THE WISCONSIN INSTITUTE FOR TORAH STUDY 3288 N. Lake Dr. Milwaukee, WI 53211 (414) 963-9317 PLEASE TYPE OR PRINT CLEARLY APPLICANT APPLICANT'S NAME (LAST) FIRST M.I. HEBREW NAME APPLICANT'S ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE HOME PHONE PRIMARY FAMILY E-MAIL ADDRESS PRESENT SCHOOL PRESENT GRADE PLACE OF BIRTH DATE OF BIRTH NAME PREFERRED TO BE CALLED PARENTS FATHER’S NAME (LAST) FIRST TITLE HEBREW NAME FATHER'S ADDRESS - (if different from above) CITY STATE ZIP CODE FATHER'S OCCUPATION HOME PHONE EMAIL ADDRESS CELL PHONE OFFICE PHONE SYNAGOGUE AFFILIATION SYNAGOGUE RABBI MOTHER'S NAME (LAST) FIRST TITLE MAIDEN NAME HEBREW NAME MOTHER'S ADDRESS - (if different from above) CITY STATE ZIP CODE MOTHER'S OCCUPATION HOME PHONE (if different from above) CELL PHONE OFFI CE PHONE EMAIL ADDRESS SYNAGOGUE AFFILIATION – (if different from above) SYNAGOGUE RABBI – (if different from above) PARENTS' AFFILIATION WITH JEWISH ORGANIZATIONS, (RELIGIOUS, COMMUNAL, EDUCATIONAL, ETC.) SIBLINGS NAME SCHOOL AGE GRADE EDUCATIONAL DATA LIST CHRONOLOGICALLY ALL THE SCHOOLS THAT APPLICANT HAS ATTENDED NAME OF SCHOOL CITY DATES OF ATTENDANCE GRADUATED (Y OR N) DESCRIBE THE COURSES APPLICANT HAS TAKEN THIS YEAR GEMORAH: Include the mesechta currently being learned, the amount of blatt expected to be learned this year, the length of the Gemorah shiur each day and the meforshim regularly learned MATH: Provide course name and describe the material studied EXTRA CURRICULAR LEARNING: Describe any learning outside of school (Limud, Days, Time) LIST CHRONOLOGICALLY THE SUMMER CAMPS THAT APPLICANT HAS ATTENDED NAME CITY DATES IN WHICH ORGANIZATIONS AND/OR EXTRA CURRICULAR ACTIVITIES HAS APPLICANT PARTICIPATED IN SCHOOL AND IN THE COMMUNITY? NAME DATES INDEPENDENT EVALUATIONS Section 1 Has your son ever been evaluated or diagnosed for any developmental or learning issues? Yes No If yes, please state the reason or nature of the tests. -

Preparing a Dvar Torah

PREPARING A DVAR TORAH GUIDELINES AND RESOURCES Preparing a dvar Torah 1 Preparing a dvar Torah 2 Preparing a dvar Torah 1 MANY PEOPLE WHO ARE ASKED TO GIVE a dvar Torah don't know where to begin. Below are some simple guidelines and instructions. It is difficult to provide a universal recipe because there are many different divrei Torah models depending on the individual, the context, the intended audience and the weekly portion that they are dealing with! However, regardless of content, and notwithstanding differences in format and length, all divrei Torah share some common features and require similar preparations. The process is really quite simple- although the actual implementation is not always so easy. The steps are as follows: Step One: Understand what a dvar Torah is Step Two: Choose an issue or topic (and how to find one) Step Three: Research commentators to explore possible solutions Step Four: Organize your thoughts into a coherent presentation 1Dvar Torah: literallly, 'a word of Torah.' Because dvar means 'a word of...' (in the construct form), please don't use the word dvar without its necessary connected direct object: Torah. Instead, you can use the word drash, which means a short, interpretive exposition. Preparing a dvar Torah 3 INTRO First clarify what kind of dvar Torah are you preparing. Here are three common types: 1. Some shuls / minyanim have a member present a dvar Torah in lieu of a sermon. This is usually frontal (ie. no congregational response is expected) and may be fifteen to twenty minutes long. 2. Other shuls / minyanim have a member present a dvar Torah as a jumping off point for a discussion. -

THE HALAKHIC PROCESS* J. David Bleich I. the Methodology Of

THE HALAKHIC PROCESS* J. David Bleich I. The Methodology of Halakhah Judaism is unique in its teaching that study is not merely a means but an end, and not merely an end among ends, but the highest and noblest of human aspirations. Study of Torah for its own sake is a sacramental act, the greatest of all miẓvot. Throughout the generations Torah scholars were willing to live in poverty and deprivation in order to devote themselves to study. Every Jew, regardless of the degree of erudition he had attained, devoted a portion of his time to Torah learning. Those capable of doing so plumbed the depths of the Talmud. Others perused the Mishnah or stud- ied the weekly Torah portion together with the commentary of Rashi. Even the unlettered recited psalms on a regular daily basis. To the Jew, Torah study has always been more than a ritual act; it has always been a religious experience. The Jew has always perceived God speaking to him through the leaves of the Gemara, from the paragraphs of the Shulḥan Arukh and the words of the verses of the Bible. The Sages long ago taught, “Kudsha Berikh Hu ve-Oraita ḥad,” God and the Torah are one; the Torah is the manifestation of divine wisdom. God reveals Himself to anyone who immerses himself in the depths of the Torah; the intensity of the revelation is directly propor- tionate to the depth of penetration and perceptive understanding. To the scholar, a novel, illuminating insight affords a more convincing demonstra- tion of the Divine Presence than a multitude of philosophic arguments. -

7 Easy Steps to Leading a Torah Study Session

7 Easy Steps to Leading a Torah Study Session 1. Gather information a. Find out what the Torah portion is for the week you’ll be studying i. Ask the Rabbi ii. Look at a Jewish calendar – most have the Torah portion noted on each Saturday. Each Shabbat is known by the name of the Torah portion which is read b. Decide whether you’re going to focus on the entire Torah portion, or just the reading we’ll cover in this year’s triennial portion. See pages 710‐724 in the Kol Haneshamah prayer book for the triennial readings. c. Find out how much time you will have; where you will be doing the study; and how the space will be arranged. 2. Read the Torah portion aloud. See “Resources” at the end for information about finding the translation a. Reading aloud provides the opportunity to hear the words that were written. b. It also allows us to slow down the reading instead of skimming over it. c. Listen to yourself as you read. d. Some things to look for (Source: Being Torah Teacher’s Guide; Torah Aura Publications): i. Missing Information. What information is missing? What doesn’t the Torah tell you? What information would help clarify the story or the instructions, etc? ii. Number‐words. The numbers 7, 10 and 40 are important; individual words repeated 5, 7, 10 or 12 times in a single portion are usually very important – those key words are a clue to what the portion’s about. iii. Text repetitions. The language in the Torah is specific, with no “extra” or “unnecessary” words. -

And This Is the Blessing)

V'Zot HaBerachah (and this is the blessing) Moses views the Promised Land before he dies את־ And this is the blessing, in which blessed Moses, the man of Elohim ְ ו ז ֹאת Deuteronomy 33:1 Children of Israel before his death. C-MATS Question: What were the final words of Moses? These final words of Moses are a combination of blessing and prophecy, in which he blesses each tribe according to its national responsibilities and individual greatness. Moses' blessings were a continuation of Jacob's, as if to say that the tribes were blessed at the beginning of their national existence and again as they were about to begin life in Israel. Moses directed his blessings to each of the tribes individually, since the welfare of each tribe depended upon that of the others, and the collective welfare of the nation depended upon the success of them all (Pesikta). came from Sinai and from Seir He dawned on them; He shined forth from יהוה ,And he (Moses) said 2 Mount Paran and He came with ten thousands of holy ones: from His right hand went a fiery commandment for them. came to Israel from Seir and יהוה ?present the Torah to the Israelites יהוה Question: How did had offered the Torah to the descendants of יהוה Paran, which, as the Midrash records, recalls that Esau, who dwelled in Seir, and to the Ishmaelites, who dwelled in Paran, both of whom refused to accept the Torah because it prohibited their predilections to kill and steal. Then, accompanied by came and offered His fiery Torah to the Israelites, who יהוה ,some of His myriads of holy angels submitted themselves to His sovereignty and accepted His Torah without question or qualification. -

Zebulun and Issachar As an Ethical Paradigm

ZEBULUN AND ISSACHAR AS AN ETHICAL PARADIGM hy S. DANIEL BRESLAUER University of Kansas, Lawrence A paradigm, it has been remarked (Blank, I974, pp. I I If.), can be either a boring linguistic model or a rather exciting literary image with its own evolutionary history.' Ethical models often rely upon paradigms as a means of inspiring certain types of behavior patterns. Often, how ever, paradigms seem to conflict. In later Judaism this conflict often revolved around the tension between the paradigm of the pious doer of l)esed, deeds of lovingkindness, and the paradigm of the scholar. Norman Lamm ( 1971, pp. 212-246) has investigated this tension. He suggests that the Musar Movement, while attractive, has problematic implications for normative Judaism. It holds up the model of ethical piety in contrast to that of Torah scholarship. He contends that the great leaders in Judaism managed to combine a sensitivity to morality-that which lies beyond the line of the law-with intensive scholarship and dedication to the letter of the law itself. The ideal should be, he suggests, the scholar who makes room for deeds of love only when they do not conflict with the primary duty of Torah study. This ideal and the tension it reflects found expression in rabbinic exegesis through the paradigm of the partnership between Issachar and Zebulun. The relationship between these two was inferred from two ancient poems, both of which are obscure and have presented modern scholars with problems of interpretation as any of the modern commen taries demonstrate: Genesis 49 and Deuteronomy 33 (see for example Speiser, 1964 and Von Rad, 1966). -

Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures

Oral Tradition, 25/1 (2010): 41-56 Guarding Oral Transmission: Within and Between Cultures Talya Fishman Like their rabbinic Jewish predecessors and contemporaries, early Muslims distinguished between teachings made known through revelation and those articulated by human tradents. Efforts were made throughout the seventh century—and, in some locations, well into the ninth— to insure that the epistemological distinctness of these two culturally authoritative corpora would be reflected and affirmed in discrete modes of transmission. Thus, while the revealed Qur’an was transmitted in written compilations from the time of Uthman, the third caliph (d. 656), the inscription of ḥadīth, reports of the sayings and activities of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, was vehemently opposed—even after writing had become commonplace. The zeal with which Muslim scholars guarded oral transmission, and the ingenious strategies they deployed in order to preserve this practice, attracted the attention of several contemporary researchers, and prompted one of them, Michael Cook, to search for the origins of this cultural impulse. After reviewing an array of possible causes that might explain early Muslim zeal to insure that aḥadīth were relayed solely through oral transmission,1 Cook argued for “the Jewish origin of the Muslim hostility to the writing of tradition” (1997:442).2 The Arabic evidence he cites consists of warnings to Muslims that ḥadīth inscription would lead them to commit the theological error of which contemporaneous Jews were guilty (501-03): once they inscribed their Mathnā, that is, Mishna, Jews came to regard this repository of human teachings as a source of authority equal to that of revealed Scripture (Ibn Sacd 1904-40:v, 140; iii, 1).3 As Jewish evidence for his claim, Cook cites sayings by Palestinian rabbis of late antiquity and by writers of the geonic era, which asserted that extra-revelationary teachings are only to be relayed through oral transmission (1997:498-518). -

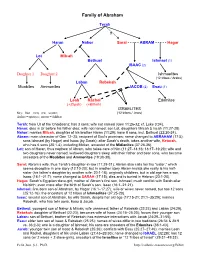

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

A Midrash on Rotulus from Damira, Its Materiality, Scribe, and Date

29 2 Reading in the Provinces: A Midrash on Rotulus from Damira, Its Materiality, Scribe, and Date JUDITH OLSZOWY-SCHLANGER ÉCOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ÉTUDES, SORBONNE, PARIS 30 Judith Olszowy-Schlanger Reading in the Provinces: A Midrash on Rotulus from Damira, Its Materiality, Scribe, and Date 31 ‘A battlefield of books’: this is how Solomon Schechter described the mass of tangled and damaged manuscript debris when he entered the Genizah chamber of the Ben Ezra synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo) in 1896 (fig. 2.1). This windowless room, together with similar caches in other synagogues and in the cemetery Basatin in Cairo, yielded over 350,000 fragments of manuscripts, kept today in more than seventy collections worldwide.1 Most of the fragments date from the Fatimid and Ayyubid periods: more than ninety-five percent come from books while the rest are fragments of legal documents, letters, and other pragmatic writings. They were preserved thanks to the long-standing Jewish tradition of disposing of old writings with particular respect, founded on the belief that Hebrew texts containing the name of God are sacred: rather than being destroyed or thrown away, worn out books and documents—both holy and trivial—were instead placed in dedicated space, a Genizah, to decay naturally without human intervention. This massive necropolis of discarded writings offers us unprecedented knowledge of Jewish life in Fig. 2.1 medieval Egypt in general and of Jewish book history in particular. Thousands of fragments are Solomon Schechter witnesses to the centrality of Hebrew books in liturgy, in professional activities, and in private at work in the Old University Library, life, as well as offering a mine of information about how these books were made and read: their Cambridge. -

The Twelve Tribes of Israel by Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D

The Twelve Tribes of Israel by Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D. In the Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament), the Israelites are described as descendants of the twelve sons of Jacob (whose name was changed to Israel in Gen 32:28), the son of Isaac, the son of Abraham. The phrase "Twelve Tribes of Israel" (or simply "Twelve Tribes") sometimes occurs in the Bible (OT & NT) without any individual names being listed (Gen 49:28; Exod 24:4; 28:21; 39:14; Ezek 47:13; Matt 19:28; Luke 22:30; Acts 26:7; and Rev 21:12; cf. also "Twelve Tribes of the Dispersion" in James 1:1). More frequently, however, the names are explicitly mentioned. The Bible contains two dozen listings of the twelve sons of Jacob and/or tribes of Israel. Some of these are in very brief lists, while others are spread out over several paragraphs or chapters that discuss the distribution of the land or name certain representatives of each tribe, one after another. Surprisingly, however, each and every listing is slightly different from all the others, either in the order of the names mentioned or even in the specific names used (e.g., the two sons of Joseph are sometimes listed along with or instead of their father; and sometimes one or more names is omitted for various reasons). A few of the texts actually have more than 12 names! Upon closer analysis, one can discover several principles for the ordering and various reasons for the omission or substitution of some of the names, as explained in the notes below the following tables.