C I E S M W O R K S H O P S E R I E S African Continental Margins of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Contrasting Phanerozoic Orogenic Systems Revealed by Hafnium Isotope Data William J

ARTICLES PUBLISHED ONLINE: 17 APRIL 2011 | DOI: 10.1038/NGEO1127 Two contrasting Phanerozoic orogenic systems revealed by hafnium isotope data William J. Collins1*(, Elena A. Belousova2, Anthony I. S. Kemp1 and J. Brendan Murphy3 Two fundamentally different orogenic systems have existed on Earth throughout the Phanerozoic. Circum-Pacific accretionary orogens are the external orogenic system formed around the Pacific rim, where oceanic lithosphere semicontinuously subducts beneath continental lithosphere. In contrast, the internal orogenic system is found in Europe and Asia as the collage of collisional mountain belts, formed during the collision between continental crustal fragments. External orogenic systems form at the boundary of large underlying mantle convection cells, whereas internal orogens form within one supercell. Here we present a compilation of hafnium isotope data from zircon minerals collected from orogens worldwide. We find that the range of hafnium isotope signatures for the external orogenic system narrows and trends towards more radiogenic compositions since 550 Myr ago. By contrast, the range of signatures from the internal orogenic system broadens since 550 Myr ago. We suggest that for the external system, the lower crust and lithospheric mantle beneath the overriding continent is removed during subduction and replaced by newly formed crust, which generates the radiogenic hafnium signature when remelted. For the internal orogenic system, the lower crust and lithospheric mantle is instead eventually replaced by more continental lithosphere from a collided continental fragment. Our suggested model provides a simple basis for unravelling the global geodynamic evolution of the ancient Earth. resent-day orogens of contrasting character can be reduced to which probably began by the Early Ordovician12, and the Early two types on Earth, dominantly accretionary or dominantly Paleozoic accretionary orogens in the easternmost Altaids of Pcollisional, because only the latter are associated with Wilson Asia13. -

Neoproterozoic Glaciations in a Revised Global Palaeogeography from the Breakup of Rodinia to the Assembly of Gondwanaland

Sedimentary Geology 294 (2013) 219–232 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Sedimentary Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sedgeo Invited review Neoproterozoic glaciations in a revised global palaeogeography from the breakup of Rodinia to the assembly of Gondwanaland Zheng-Xiang Li a,b,⁎, David A.D. Evans b, Galen P. Halverson c,d a ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CCFS) and The Institute for Geoscience Research (TIGeR), Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, WA 6845, Australia b Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA c Earth & Planetary Sciences/GEOTOP, McGill University, 3450 University St., Montreal, Quebec H3A0E8, Canada d Tectonics, Resources and Exploration (TRaX), School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia article info abstract Article history: This review paper presents a set of revised global palaeogeographic maps for the 825–540 Ma interval using Received 6 January 2013 the latest palaeomagnetic data, along with lithological information for Neoproterozoic sedimentary basins. Received in revised form 24 May 2013 These maps form the basis for an examination of the relationships between known glacial deposits, Accepted 28 May 2013 palaeolatitude, positions of continental rifting, relative sea-level changes, and major global tectonic events Available online 5 June 2013 such as supercontinent assembly, breakup and superplume events. This analysis reveals several fundamental ’ Editor: J. Knight palaeogeographic features that will help inform and constrain models for Earth s climatic and geodynamic evolution during the Neoproterozoic. First, glacial deposits at or near sea level appear to extend from high Keywords: latitudes into the deep tropics for all three Neoproterozoic ice ages (Sturtian, Marinoan and Gaskiers), al- Neoproterozoic though the Gaskiers interval remains very poorly constrained in both palaeomagnetic data and global Rodinia lithostratigraphic correlations. -

Balkatach Hypothesis: a New Model for the Evolution of the Pacific, Tethyan, and Paleo-Asian Oceanic Domains

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Balkatach hypothesis: A new model for the evolution of the Pacific, Tethyan, and Paleo-Asian oceanic domains 1,2 2 GEOSPHERE, v. 13, no. 5 Andrew V. Zuza and An Yin 1Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA 2Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095-1567, USA doi:10.1130/GES01463.1 18 figures; 2 tables; 1 supplemental file ABSTRACT suturing. (5) The closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean in the early Permian was accompanied by a widespread magmatic flare up, which may have been CORRESPONDENCE: avz5818@gmail .com; The Phanerozoic history of the Paleo-Asian, Tethyan, and Pacific oceanic related to the avalanche of the subducted oceanic slabs of the Paleo-Asian azuza@unr .edu domains is important for unraveling the tectonic evolution of the Eurasian Ocean across the 660 km phase boundary in the mantle. (6) The closure of the and Laurentian continents. The validity of existing models that account for Paleo-Tethys against the southern margin of Balkatach proceeded diachro- CITATION: Zuza, A.V., and Yin, A., 2017, Balkatach hypothesis: A new model for the evolution of the the development and closure of the Paleo-Asian and Tethyan Oceans criti- nously, from west to east, in the Triassic–Jurassic. Pacific, Tethyan, and Paleo-Asian oceanic domains: cally depends on the assumed initial configuration and relative positions of Geosphere, v. 13, no. 5, p. 1664–1712, doi:10.1130 the Precambrian cratons that separate the two oceanic domains, including /GES01463.1. the North China, Tarim, Karakum, Turan, and southern Baltica cratons. -

Kinematics and Extent of the Piemont-Liguria Basin

https://doi.org/10.5194/se-2020-161 Preprint. Discussion started: 8 October 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Kinematics and extent of the Piemont-Liguria Basin – implications for subduction processes in the Alps Eline Le Breton1, Sascha Brune2,3, Kamil Ustaszewski4, Sabin Zahirovic5, Maria Seton5, R. Dietmar Müller5 5 1Department of Earth Sciences, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany 2Geodynamic Modelling Section, German Research Centre for Geosciences, GFZ Potsdam, Germany 3Institute of Geosciences, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany 4Institute for Geological Sciences, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany 10 5EarthByte Group, School of Geosciences, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Correspondence to: Eline Le Breton ([email protected]) Abstract. Assessing the size of a former ocean, of which only remnants are found in mountain belts, is challenging but crucial to understand subduction and exhumation processes. Here we present new constraints on the opening and width of the Piemont- Liguria (PL) Ocean, known as the Alpine Tethys together with the Valais Basin. We use a regional tectonic reconstruction of 15 the Western Mediterranean-Alpine area, implemented into a global plate motion model with lithospheric deformation, and 2D thermo-mechanical modelling of the rifting phase to test our kinematic reconstructions for geodynamic consistency. Our model fits well with independent datasets (i.e. ages of syn-rift sediments, rift-related fault activity and mafic rocks) and shows that the PL Basin opened in four stages: (1) Rifting of the proximal continental margin in Early Jurassic (200-180 Ma), (2) Hyper- extension of the distal margin in Early-Middle Jurassic (180-165 Ma), (3) Ocean-Continent Transition (OCT) formation with 20 mantle exhumation and MORB-type magmatism in Middle-Late Jurassic (165-154 Ma), (4) Break-up and “mature” oceanic spreading mostly in Late Jurassic (154-145 Ma). -

Inherited Zircons Reveal a Gondwana Continental Fragment Beneath East Java, Indonesia ⁎ H.R

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 258 (2007) 269–282 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl The deep crust beneath island arcs: Inherited zircons reveal a Gondwana continental fragment beneath East Java, Indonesia ⁎ H.R. Smyth a, , P.J. Hamilton b, R. Hall a, P.D. Kinny b a SE Asia Research Group, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey TW200EX, UK b Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University of Technology, Perth 6845, Australia Received 21 November 2006; received in revised form 21 March 2007; accepted 21 March 2007 Available online 1 April 2007 Editor: R.W. Carlson Abstract Inherited zircons in Cenozoic sedimentary and igneous rocks of East Java range in age from Archean to Cenozoic. The distribution of zircons reveals two different basement types at depth. The igneous rocks of the Early Cenozoic arc, found along the southeast coast, contain only Archean to Cambrian zircons. In contrast, clastic rocks of north and west of East Java contain Cretaceous zircons, which are not found in the arc rocks to the south. The presence of Cretaceous zircons supports previous interpretations that much of East Java is underlain by arc and ophiolitic rocks, accreted to the Southeast Asian margin during Cretaceous subduction. However, such accreted material cannot account for the older zircons. The age populations of Archean to Cambrian zircons in the arc rocks are similar to Gondwana crust. We interpret the East Java Early Cenozoic arc to be underlain by a continental fragment of Gondwana origin and not Cretaceous material as previously suggested. Melts rising through the crust, feeding the Early Cenozoic arc, picked up the ancient zircons through assimilation or partial melting. -

54. Mesozoic–Tertiary Tectonic Evolution of the Easternmost Mediterranean Area: Integration of Marine and Land Evidence1

Robertson, A.H.F., Emeis, K.-C., Richter, C., and Camerlenghi, A. (Eds.), 1998 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 160 54. MESOZOIC–TERTIARY TECTONIC EVOLUTION OF THE EASTERNMOST MEDITERRANEAN AREA: INTEGRATION OF MARINE AND LAND EVIDENCE1 Alastair H.F. Robertson2 ABSTRACT This paper presents a synthesis of Holocene to Late Paleozoic marine and land evidence from the easternmost Mediterra- nean area, in the light of recent ODP Leg 160 drilling results from the Eratosthenes Seamount. The synthesis is founded on three key conclusions derived from marine- and land-based study over the last decade. First, the North African and Levant coastal and offshore areas represent a Mesozoic rifted continental margin of Triassic age, with the Levantine Basin being under- lain by oceanic crust. Second, Mesozoic ophiolites and related continental margin units in southern Turkey and Cyprus repre- sent tectonically emplaced remnants of a southerly Neotethyan oceanic basin and are not far-travelled units derived from a single Neotethys far to the north. Third, the present boundary of the African and Eurasian plates runs approximately east-west across the easternmost Mediterranean and is located between Cyprus and the Eratosthenes Seamount. The marine and land geology of the easternmost Mediterranean is discussed utilizing four north-south segments, followed by presentation of a plate tectonic reconstruction for the Late Permian to Holocene time. INTRODUCTION ocean (Figs. 2, 3; Le Pichon, 1982). The easternmost Mediterranean is defined as that part of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea located east ° The objective here is to integrate marine- and land-based geolog- of the Aegean (east of 28 E longitude). -

Arc-Continent Collision and the Formation of Continental Crust: a New Geochemical and Isotopic Record from the Ordovician Tyrone Igneous Complex, Ireland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Woods Hole Open Access Server Arc-Continent Collision and the Formation of Continental Crust: A New Geochemical and Isotopic Record from the Ordovician Tyrone Igneous Complex, Ireland Amy E. Draut U.S. Geological Survey, Santa Cruz, CA 95060, U.S.A. [email protected] Peter D. Clift School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, United Kingdom Jeffrey M. Amato Department of Geological Sciences, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, U.S.A. Jerzy Blusztajn and Hans Schouten Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, U.S.A. Abstract Collisions between oceanic island-arc terranes and passive continental margins are thought to have been important in the formation of continental crust throughout much of Earth’s history. Magmatic evolution during this stage of the plate-tectonic cycle is evident in several areas of the Ordovician Grampian-Taconic Orogen, as we demonstrate in the first detailed geochemical study of the Tyrone Igneous Complex, Ireland. New U– Pb zircon dating yields ages of 493 ± 2 Ma from a primitive mafic intrusion, indicating intra-oceanic subduction in Tremadoc time, and 475 ± 10 Ma from a light-rare-earth- element (LREE)-enriched tonalite intrusion that incorporated Laurentian continental material by early Arenig time (Early Ordovician, Stage 2) during arc-continent collision. Notably, LREE enrichment in volcanism and silicic intrusions of the Tyrone Igneous Draut et al. page 1 of 27 Complex exceeds that of average Dalradian (Laurentian) continental material which would have been thrust under the colliding forearc and potentially recycled into arc magmatism. -

Middle Jurassic Collision of an Exotic Microcontinental Fragment: Impli- Cations for Magmatism Across the Southeast China Continental Margin

Middle Jurassic collision of an exotic microcontinental fragment: Impli- cations for magmatism across the southeast China continental margin Roderick J. Sewell a*, Andrew Carter b & Martin Rittner c aHong Kong Geological Survey, Geotechnical Engineering Office, Civil Engineering and Development Department, 101 Princess Margaret Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. b Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, UK cDepartment of Earth Science, University College, London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Thrusting, folding and metamorphism of late Paleozoic to middle Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, to- gether with high precision U–Pb zircon ages from Middle to Late Jurassic volcanic and granitic rocks, Article history reveals evidence for a major deformation event in northwestern Hong Kong between 164 and 161 Ma. This episode can be linked with collision of an exotic microcontinental fragment along the southeast Keywords China continental margin determined from contrasting detrital zircon provenance histories of late Pa- Gondwana leozoic to middle Mesozoic sedimentary rocks either side of a NE-trending suture zone through cen- Hong Kong tral Hong Kong. The suture zone is also reflected by isotopic heterogeneities and geophysical anoma- Middle Jurassic lies in the crustal basement. Detrital zircon provenance of Early to Middle Jurassic rocks from the Terrane accretion accreted terrane have little in common with the pre-Middle Jurassic rocks from southeast China. In- Zircon provenance stead, the zircon age spectra of the accreted terrane show close affinities to sources along the northern margin of east Gondwana. These data provide indisputable evidence for Mesozoic terrane accretion along the southeast China continental margin. -

Precambrian Ophiolites of Arabia: a Summary of Geologic Settings U-Pb

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Precambrian ophiolites of Arabia: A summary of geologic settings U-Pb geochronology, lead isotope characteristics, and implications for microplate accretion, kingdom of Saudi Arabia by J. S. Pal lister!/, J. S. StaceyZ/, L. B. Fischer and W. R. Premo Open-File Report Report prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey in cooperation with the Deputy Ministry for Mineral Resources, Saudi Arabia This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. JV U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, CO 2/ U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA 1988 CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT.................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................. 2 Ophiolites and the Arabian Shield..................... 2 A note on stratigraphic nomenclature.................. 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS........................................... 6 GEOLOGIC AND TECTONIC SETTINGS, SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS....... 6 Northwest and west-central Arabian Shield............. 7 Jabal Ess ophiolite............................... 7 Jabal al Wask complex............................. 12 Nabt complex and the Kamal intrusion.............. 17 Thurwah ophiolite..................................... 18 Bir Umg complex................................... 21 Nabitah suture zone................................... 25 Bir Tuluhah complex .............................. 25 Ad Dafinah belt .................................. 27 Tathlith and Hamdah -

THE TECTONIC RELATIONSHIPS of the HILLABEE CHLORITE SCHIST and the ADJACENT ROCK UNITS in SOUTHERN CLEBURNE COUNTY, ALABAMA by B

THE TECTONIC RELATIONSHIPS OF THE HILLABEE CHLORITE SCHIST AND THE ADJACENT ROCK UNITS IN SOUTHERN CLEBURNE COUNTY, ALABAMA by BERTRAM HAYES-DAVIS A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Geological Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA 1979 ABSTRACT In southern Cleburne County, Alabama, the Coosa block is thrust over the Talladega block along the Hollins Line thrust fault. The Talladega block is composed of low grade metamorphic rocks, and contains evidence for four structural events. The units in the Talladega block indicate a continental origin for the depositional environment. Within the Talladega block, geochemical analyses indicate that the Hillabee Chlorite Schist, known as the Hillabee Greenstone, is associated with island arc volcanic activity and may represent distal lava flows. The Coosa block is composed of a high-grade metasedimentary sequence and amphibolite, and also shows evidence of four structural events. The Poe Bridge Mountain amphibolite of the Coosa block has an unrelated origin to the Hillabee Greenstone. Origin of the Talladega block units is related to subduction associated with an island arc-continental fragment collision of sedimentary-volcanic rock. During this collision, F1-folds were formed which are found both in the Talladega and Coosa blocks. Continued collision of North America and Africa possibly created the F2-F3 folds, the Hollins Line fault, and subsequently the F4 folds found in both blocks. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the encouragement and guidance provided by Dr. James F. -

North China Craton: the Conjugate Margin for Northwestern Laurentia in Rodinia Jikai Ding1,2, Shihong Zhang1,3*, David A.D

https://doi.org/10.1130/G48483.1 Manuscript received 7 October 2020 Revised manuscript received 27 December 2020 Manuscript accepted 12 January 2021 © 2021 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 22 March 2021 North China craton: The conjugate margin for northwestern Laurentia in Rodinia Jikai Ding1,2, Shihong Zhang1,3*, David A.D. Evans2, Tianshui Yang1, Haiyan Li1, Huaichun Wu1 and Jianping Chen3 1 State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China 2 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, USA 3 School of Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China ABSTRACT ern NCC and northwestern Laurentia (present In the Rodinia supercontinent, Laurentia is placed at the center because it was flanked coordinates) was proposed (Fu et al., 2015; by late Neoproterozoic rifted margins; however, the conjugate margin for western Laurentia Zhao et al., 2020) but required rigorous testing is still enigmatic. In this study, new paleomagnetic results have been obtained from 15 ca. by coeval pairs of high-quality poles with pre- 775 Ma mafic dikes in eastern Hebei Province, North China craton (NCC). Stepwise thermal cise age constraints. In this study, we report a demagnetization revealed a high-temperature component, directed northeast or southwest new high-quality paleomagnetic pole obtained with shallow inclinations, with unblocking temperatures of as high as 580 °C. Rock magne- from ca. 775 Ma mafic dikes in the eastern He- tism suggests the component is carried by single-domain and pseudo-single-domain magnetite bei Province, NCC. -

Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

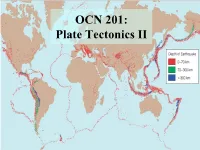

OCN 201: Plate Tectonics II There are three types of plate boundaries: a) mid-ocean ridge, subduction zone, transform fault b) divergent, convergent, translational c) constructive, destructive, conservative d) All of the above: a,b, and c all describe the 3 types. Structure of Continents • Continental crust has formed throughout Earth’s history by chemical differentiation at subduction zones. – Oceanic crust: dry melting of mantle at MOR basalt – Continental crust: wet melting in subduction zones andesite of volcanic arcs Subducted H2O is from the oceans, in seafloor sediment and weathered oceanic crust. H2O comes off subducted plate as it heats, rises into mantle of plate above, and X lowers its melting temperature. Structure of Continents Continental crust exists on Earth because we have – Liquid water oceans – Subduction (Plate Tectonics) – Venus lacks liquid H2O and subduction zones no continental crust (and Venus’s mantle is too stiff and dry to convect!) Hypsometric curves: Shape of the solid surface of Earth vs. Venus Structure of Continents Oldest oceanic crust ~ 170 million years Oldest continental crust = 4.03 billion years (in Canada) What do the continents tell us about Earth history? Cratons vs. mobile belts: Terranes and Structure of Continents • Continental crust is too thick and buoyant to subduct. • When continental fragment or island arc collides with continent it “sticks”. Terranes and Structure of Continents • Fragments of cont. crust incorporated into larger cont. masses are called terranes. • Younger terranes are parts of mobile belts. • Older now stable parts (cratons) appear to have accreted as terranes in the more distant past. Terrane Structure of North America • North America age distribution illustrates terrane accretion.