The Concept of the Earth's Shape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photochemically Driven Collapse of Titan's Atmosphere

REPORTS has escaped, the surface temperature again Photochemically Driven Collapse decreases, down to about 86 K, slightly of Titan’s Atmosphere above the equilibrium temperature, because of the slight greenhouse effect resulting Ralph D. Lorenz,* Christopher P. McKay, Jonathan I. Lunine from the N2 opacity below (longward of) 200 cm21. Saturn’s giant moon Titan has a thick (1.5 bar) nitrogen atmosphere, which has a These calculations assume the present temperature structure that is controlled by the absorption of solar and thermal radiation solar constant of 15.6 W m22 and a surface by methane, hydrogen, and organic aerosols into which methane is irreversibly converted albedo of 0.2 and ignore the effects of N2 by photolysis. Previous studies of Titan’s climate evolution have been done with the condensation. As noted in earlier studies assumption that the methane abundance was maintained against photolytic depletion (5), when the atmosphere cools during the throughout Titan’s history, either by continuous supply from the interior or by buffering CH4 depletion, the model temperature at by a surface or near surface reservoir. Radiative-convective and radiative-saturated some altitudes in the atmosphere (here, at equilibrium models of Titan’s atmosphere show that methane depletion may have al- ;10 km for 20% CH4 surface humidity) lowed Titan’s atmosphere to cool so that nitrogen, its main constituent, condenses onto becomes lower than the saturation temper- the surface, collapsing Titan into a Triton-like frozen state with a thin atmosphere. -

Light, Color, and Atmospheric Optics

Light, Color, and Atmospheric Optics GEOL 1350: Introduction To Meteorology 1 2 • During the scattering process, no energy is gained or lost, and therefore, no temperature changes occur. • Scattering depends on the size of objects, in particular on the ratio of object’s diameter vs wavelength: 1. Rayleigh scattering (D/ < 0.03) 2. Mie scattering (0.03 ≤ D/ < 32) 3. Geometric scattering (D/ ≥ 32) 3 4 • Gas scattering: redirection of radiation by a gas molecule without a net transfer of energy of the molecules • Rayleigh scattering: absorption extinction 4 coefficient s depends on 1/ . • Molecules scatter short (blue) wavelengths preferentially over long (red) wavelengths. • The longer pathway of light through the atmosphere the more shorter wavelengths are scattered. 5 • As sunlight enters the atmosphere, the shorter visible wavelengths of violet, blue and green are scattered more by atmospheric gases than are the longer wavelengths of yellow, orange, and especially red. • The scattered waves of violet, blue, and green strike the eye from all directions. • Because our eyes are more sensitive to blue light, these waves, viewed together, produce the sensation of blue coming from all around us. 6 • Rayleigh Scattering • The selective scattering of blue light by air molecules and very small particles can make distant mountains appear blue. The blue ridge mountains in Virginia. 7 • When small particles, such as fine dust and salt, become suspended in the atmosphere, the color of the sky begins to change from blue to milky white. • These particles are large enough to scatter all wavelengths of visible light fairly evenly in all directions. -

Project Horizon Report

Volume I · SUMMARY AND SUPPORTING CONSIDERATIONS UNITED STATES · ARMY CRD/I ( S) Proposal t c• Establish a Lunar Outpost (C) Chief of Ordnance ·cRD 20 Mar 1 95 9 1. (U) Reference letter to Chief of Ordnance from Chief of Research and Devel opment, subject as above. 2. (C) Subsequent t o approval by t he Chief of Staff of reference, repre sentatives of the Army Ballistic ~tissiles Agency indicat e d that supplementar y guidance would· be r equired concerning the scope of the preliminary investigation s pecified in the reference. In particular these r epresentatives requested guidance concerning the source of funds required to conduct the investigation. 3. (S) I envision expeditious development o! the proposal to establish a lunar outpost to be of critical innportance t o the p. S . Army of the future. This eva luation i s appar ently shar ed by the Chief of Staff in view of his expeditious a pproval and enthusiastic endorsement of initiation of the study. Therefore, the detail to be covered by the investigation and the subs equent plan should be as com plete a s is feas ible in the tin1e limits a llowed and within the funds currently a vailable within t he office of t he Chief of Ordnance. I n this time of limited budget , additional monies are unavailable. Current. programs have been scrutinized r igidly and identifiable "fat'' trimmed awa y. Thus high study costs are prohibitive at this time , 4. (C) I leave it to your discretion t o determine the source and the amount of money to be devoted to this purpose. -

Models for Earth and Maps

Earth Models and Maps James R. Clynch, Naval Postgraduate School, 2002 I. Earth Models Maps are just a model of the world, or a small part of it. This is true if the model is a globe of the entire world, a paper chart of a harbor or a digital database of streets in San Francisco. A model of the earth is needed to convert measurements made on the curved earth to maps or databases. Each model has advantages and disadvantages. Each is usually in error at some level of accuracy. Some of these error are due to the nature of the model, not the measurements used to make the model. Three are three common models of the earth, the spherical (or globe) model, the ellipsoidal model, and the real earth model. The spherical model is the form encountered in elementary discussions. It is quite good for some approximations. The world is approximately a sphere. The sphere is the shape that minimizes the potential energy of the gravitational attraction of all the little mass elements for each other. The direction of gravity is toward the center of the earth. This is how we define down. It is the direction that a string takes when a weight is at one end - that is a plumb bob. A spirit level will define the horizontal which is perpendicular to up-down. The ellipsoidal model is a better representation of the earth because the earth rotates. This generates other forces on the mass elements and distorts the shape. The minimum energy form is now an ellipse rotated about the polar axis. -

Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth's Immobility

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 12-28-1953 Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth's Immobility John Robinson Windham College Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Recommended Citation Robinson, John, "Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth's Immobility" (1953). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 263. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/263 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN ROBINSON Windham College Anaximander and the Problem of the Earth’s Immobility* N the course of his review of the reasons given by his predecessors for the earth’s immobility, Aristotle states that “some” attribute it I neither to the action of the whirl nor to the air beneath’s hindering its falling : These are the causes with which most thinkers busy themselves. But there are some who say, like Anaximander among the ancients, that it stays where it is because of its “indifference” (όμοιότητα). For what is stationed at the center, and is equably related to the extremes, has no reason to go one way rather than another—either up or down or sideways. And since it is impossible for it to move simultaneously in opposite directions, it necessarily stays where it is.1 The ascription of this curious view to Anaximander appears to have occasioned little uneasiness among modern commentators. -

Links to Education Standards • Introduction to Exoplanets • Glossary of Terms • Classroom Activities Table of Contents Photo © Michael Malyszko Photo © Michael

an Educator’s Guid E INSIDE • Links to Education Standards • Introduction to Exoplanets • Glossary of Terms • Classroom Activities Table of Contents Photo © Michael Malyszko Photo © Michael For The TeaCher About This Guide .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Connections to Education Standards ................................................................................................... 5 Show Synopsis .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Meet the “Stars” of the Show .................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction to Exoplanets: The Basics .................................................................................................. 9 Delving Deeper: Teaching with the Show ................................................................................................13 Glossary of Terms ..........................................................................................................................................24 Online Learning Tools ..................................................................................................................................26 Exoplanets in the News ..............................................................................................................................27 During -

PORTALS Literary and Arts Magazine

PORTALS Literary and Arts Magazine Editors Jada Ach Jason Chaffin Kerrie Holian Gary Hurley Ted Koch Meredith Merrill John Metzger Editorial Assistants Blythe Bennett Susan Clarke Lynn Ezzell Cheryl Farinholt Cindy Fischer Justin Floyd Rhonda Franklin Gary Guliksen Jody Hinson Tracy Holbrook Jacque Jebo Catherine Lee Barry Markillie Kerry Moley Marlowe Moore Daniel Ray Norris Dylan Patterson Pamela Stewart Beth Strickland Douglas Tarble Holly Waters Art/Photography Editors Ben Billingsley Deborah Onate Sherrie Whitehead Layout/Design Christopher Clark Gary Hurley Spring 2009 Volume , Issue 7 Portals Literary and Arts Magazine wishes to extend appreciation to the CFCC Student Government Association, the CFCC Foundation, and the CFCC Arts and Sciences Division for their support in making this project a reality. The 2009 Portals awards were given by Philip Jacobs, Humanities and Fine Arts Instructor, CFCC, in memory of Professor Paul H. Jacobs Professor of English University of Illinois 964-984 Portals is a publication of Cape Fear Community College student, faculty, and staff writers and artists, published by Cape Fear Community College 411 North Front Street Wilmington, NC 2840 Cover photo by Othello York All rights reserved. Material herein may not be repro- duced or quoted without the permission of the authors. All rights revert to authors after first serial publication. 2 Table of Contents Poetry Skylar Cole, The House in the Garden of Eden 4 Matthew Maya, Peanut Butter Kisses 6 Jeremy F. Morris, The Suit Job That Never Suited Him 6 Seth Aaron Rodriguez, Brainwash 2 Teo Ninkovic, Homecoming Sarah Griffith, October 40 Carter Becerra, Blues 42 Steven R. -

Atmospheric Optics

53 Atmospheric Optics Craig F. Bohren Pennsylvania State University, Department of Meteorology, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA Phone: (814) 466-6264; Fax: (814) 865-3663; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Colors of the sky and colored displays in the sky are mostly a consequence of selective scattering by molecules or particles, absorption usually being irrelevant. Molecular scattering selective by wavelength – incident sunlight of some wavelengths being scattered more than others – but the same in any direction at all wavelengths gives rise to the blue of the sky and the red of sunsets and sunrises. Scattering by particles selective by direction – different in different directions at a given wavelength – gives rise to rainbows, coronas, iridescent clouds, the glory, sun dogs, halos, and other ice-crystal displays. The size distribution of these particles and their shapes determine what is observed, water droplets and ice crystals, for example, resulting in distinct displays. To understand the variation and color and brightness of the sky as well as the brightness of clouds requires coming to grips with multiple scattering: scatterers in an ensemble are illuminated by incident sunlight and by the scattered light from each other. The optical properties of an ensemble are not necessarily those of its individual members. Mirages are a consequence of the spatial variation of coherent scattering (refraction) by air molecules, whereas the green flash owes its existence to both coherent scattering by molecules and incoherent scattering -

Writing Region of the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards Award Recipients - Writing ALLEN, AMIRA

Richmond Art and Writing Region of the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards Award Recipients - Writing ALLEN, AMIRA Amira Allen Age: 15, Grade: 10 School Name: Manchester High School, Midlothian, VA Educator: Rebecca Lynch Category: Poetry The Middle Ground The Middle Ground “You don’t really look like you’re from here,” they say. My hooked nose sells me out. I’m not from here, But I am from rusty dog crates. From broken computers and that one skateboard trick. I am from the apartment whose rent isn’t getting paid, With too many noise complaints to count. I am from the record shop on Cary Street That held my hand as I flipped through plastic sleeves Natural melodies and hard riffs constantly echoed. I’m from snips, snails, and puppy dog tails, Because sugar just isn’t my cup of tea. from Vivian Who always forgets the lyrics, but sings anyway. But also Elizabeth Ann. I still have questions for her, but I don't think I'll ever get my answers. So, When you ask “But where are you actually from?” I might say that I’m from failed attempts to fly and a prick from a spinning wheel I’m from the right to run far away But that doesn’t mean there won’t be hurdles I’m from Henrico, but I’m also from Egypt The middle ground of indifference Where grape leaves and bologna sandwiches can be digested in peace. From the bridges my grandpa built the rules my sister broke On top of an old bookshelf In a Winnie the Pooh box that’s older than me, I am from those around me, and their dreams. -

Chapter 11: Atmosphere

The Atmosphere and the Oceans ff the Na Pali coast in Hawaii, clouds stretch toward O the horizon. In this unit, you’ll learn how the atmo- sphere and the oceans interact to produce clouds and crashing waves. You’ll come away from your studies with a deeper understanding of the common characteristics shared by Earth’s oceans and its atmosphere. Unit Contents 11 Atmosphere14 Climate 12 Meteorology15 Physical Oceanography 13 The Nature 16 The Marine Environment of Storms Go to the National Geographic Expedition on page 880 to learn more about topics that are con- nected to this unit. 268 Kauai, Hawaii 269 1111 AAtmospheretmosphere What You’ll Learn • The composition, struc- ture, and properties that make up Earth’s atmos- phere. • How solar energy, which fuels weather and climate, is distrib- uted throughout the atmosphere. • How water continually moves between Earth’s surface and the atmo- sphere in the water cycle. Why It’s Important Understanding Earth’s atmosphere and its interactions with solar energy is the key to understanding weather and climate, which con- trol so many different aspects of our lives. To find out more about the atmosphere, visit the Earth Science Web Site at earthgeu.com 270 DDiscoveryiscovery LLabab Dew Formation Dew forms when moist air near 4. Repeat the experiment outside. the ground cools and the water vapor Record the temperature of the in the air changes into water droplets. water and the air outside. In this activity, you will model the Observe In your science journal, formation of dew. describe what happened to the out- 1. -

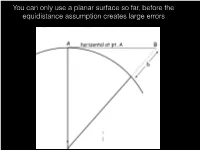

You Can Only Use a Planar Surface So Far, Before the Equidistance Assumption Creates Large Errors

You can only use a planar surface so far, before the equidistance assumption creates large errors Distance error from Kiester to Warroad is greater than two football fields in length So we assume a spherical Earth P. Wormer, wikimedia commons Longitudes are great circles, latitudes are small circles (except the Equator, which is a GC) Spherical Geometry Longitude Spherical Geometry Note: The Greek letter l (lambda) is almost always used to specify longitude while f, a, w and c, and other symbols are used to specify latitude Great and Small Circles Great circles splits the Small circles splits the earth into equal halves earth into unequal halves wikipedia geography.name All lines of equal longitude are great circles Equator is the only line of equal latitude that’s a great circle Surface distance measurements should all be along a great circle Caliper Corporation Note that great circle distances appear curved on projected or flat maps Smithsonian In GIS Fundamentals book, Chapter 2 Latitude - angle to a parallel circle, a small circle parallel to the Equatorial great circle Spherical Geometry Three measures: Latitude, Longitude, and Earth Radius + height above/ below the sphere (hp) How do we measure latitude/longitude? Well, now, GNSS, but originally, astronomic measurements: latitude by north star or solar noon angles, at equinox Longitude Measurement Method 1: The Earth rotates 360 degrees in a day, or 15 degrees per hour. If we know the time difference between 2 points, and the longitude of the first point (Greenwich), we can determine the longitude at our current location. Method 2: Create a table of moon-star distances for each day/time of the year at a reference location (Greenwich observatory) Measure the same moon-star distance somewhere else at a standard or known time. -

Extraterrestrial Geology Issue

Lite EXTRAT E RR E STRIAL GE OLO G Y ISSU E SPRING 2010 ISSUE 27 The Solar System. This illustration shows the eight planets and three of the five named dwarf planets in order of increasing distance from the Sun, although the distances between them are not to scale. The sizes of the bodies are shown relative to each other, and the colors are approximately natural. Image modified from NASA/JPL. IN TH I S ISSUE ... Extraterrestrial Geology Classroom Activity: Impact Craters • Celestial Crossword Puzzle Is There Life Beyond Earth? Meteorites in Antarctica Why Can’t I See the Milky Way? Most Wanted Mineral: Jarosite • Through the Hand Lens New Mexico’s Enchanting Geology • Short Items of Interest NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO TECH EXTRAT E RR E STRIAL GE OLO G Y Douglas Bland The surface of the planet we live on was created by geologic Many factors affect the appearance, characteristics, and processes, resulting in mountains, valleys, plains, volcanoes, geology of a body in space. Size, composition, temperature, an ocean basins, and every other landform around us. Geology atmosphere (or lack of it), and proximity to other bodies are affects the climate, concentrates energy and mineral resources just a few. Through images and data gathered by telescopes, in Earth’s crust, and impacts the beautiful landscapes outside satellites orbiting Earth, and spacecraft sent into deep space, the window. The surface of Earth is constantly changing due it has become obvious that the other planets and their moons to the relentless effects of plate tectonics that move continents look very different from Earth, and there is a tremendous and create and destroy oceans.