Keynesian Economist?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat Greg Young This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Education and Arts Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Ballarat 3353 Victoria, Australia STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Except where explicit reference is made in the text this thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree of diploma. No other person’s work has been relied upon or used without due acknowledgement in the main text and bibliography. Signed (Applicant): Date: Signed (Supervisor): Date: When the intellectual and spiritual history of the nineteenth century comes to be written, a highly interesting chapter in it will be that which records the origin, growth, decline, and disappearance of the delusion of spiritualism. —Australasian Saturday 25 October 1879 Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to my University of Ballarat (now Federation University) supervisors Dr Anne Beggs Sunter, Dr Jill Blee, and Dr David Waldron for their encouragement, advice, and criticism. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge a large debt of gratitude to Professor Tony Milner and Professor John Powers, both of the Australian National University, for their generous support. This project began in the Heritage Library of the Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute; I am grateful to the BMI for its friendly help. Dedication To Anne, Peter, Charlotte, and my teacher Dr Rafe de Crespigny. Abstract This thesis is about the origins, growth, and decline of spiritualism in nine- teenth-century Ballarat. -

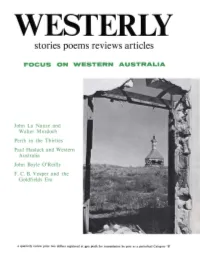

Stories Poems Reviews Articles

ESTERLY stories poems reviews articles FOCUS ON WESTERN AUSTRALIA John La Nauze and Walter Murdoch Perth in the Thirties Paul Hasluck and Western Australia John Boyle O'Reilly F. C. B. Vosper and the Goldfields Era a quarterly review price two dollars registered at gpo perth for transmission by post as a periodical Category '8 ' UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PRESS Giving the widest representation to Western Australian writers E. J. STORMON: The Salvado Memoirs $13.95 MARY ALBERTUS BAIN: Ancient Landmarks: A Social and Economic History of the Victoria District of Western Australia 1839-1894 $12.00 G. C. BOLTON: A Fine Country to Starve In $11.00 MERLE BIGNELL: The Fruit of the Country: A History of the Shire of Gnowangerup, Western Australia $12.50 R. A. FORSYTH: The Lost Pattern: Essays on the Emergent City Sensibility in Victorian England $13.60 L. BURROWS: Browning the Poet: An Introductory Study $8.25 T. GIBBONS: Rooms in the Darwin Hotel: Studies in English Literary Criticism and Ideas 1880-1920 $8.95 DOROTHY HEWETT, ED.: Sandgropers: A Western Australian Anthology $6.25 ALEC KING: The Un prosaic Imagination: Essays and Lectures on the Study of Literature $8.95 AVAILABLE ALL GOOD BOOKSELLERS Forthcoming Publications Will Include: MERAB T AUMAN: The Chief: Charles Yelverton O'Connor IAN ELLIOT: Moondyne Joe: The Man and the Myth J. E. THOMAS & Imprisonment in Western Australia: Evolution, Theory A. STEWART: and Practice The prices set out are recommended prices only. Eastern States Agents: Melbourne University Press, P.O. Box 278, Carlton South, Victoria, 3053. WESTERLY a quarterly review EDITORS: Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan EDITORIAL ADVISORS: Patrick Hutchings, Leonard Jolley, Margot Luke, Fay Zwicky Westerly is published quarterly by the English Department, University of Western Australia, with assistance from the Literature Board of' the Australia Council and the Western Australian Literary Fund. -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5. -

The Building of Economics at Adelaide

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Anderson, Kym; O'Neil, Bernard Book — Published Version The Building of Economics at Adelaide Provided in Cooperation with: University of Adelaide Press Suggested Citation: Anderson, Kym; O'Neil, Bernard (2009) : The Building of Economics at Adelaide, ISBN 978-0-9806238-5-7, University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/UPO9780980623857 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182254 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ www.econstor.eu Welcome to the electronic edition of The Building of Eco- nomics at Adelaide, 1901-2001. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 86, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2015 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Richard Broome (Convenor) Marilyn Bowler (Editor, Victorian Historical Journal) Chips Sowerwine (Editor, History News) John Rickard (Review Co-editor) Peter Yule (Review Co-editor) Jill Barnard Marie Clark Mimi Colligan Don Garden (President, RHSV) Don Gibb Richard Morton Kate Prinsley Judith Smart Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 284 VOLUME 86, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2015 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2015 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

John La Nauze

John La Nauze Australian Academy of the Humanities, Proceedings 15, 1990 JOHN ANDREW LA NAUZE 1911-1990 John La Nauze was a foundation fellow of this Academy. He was a formidable scholar who brought to Australian History a new precision, an awareness of the wider world of ideas and a concern with major problems. His pioneering studies of the history of political economy in Australia (1949), political history and constitution making ('Tariffs' 1947,1948, 1949; Alfred Deakin, 1965; The Making of the Australian Constitution, 1974) will long remain authoritative. His contributions, each founded on exhaustive research, are the more notable because his teaching career spanned the mean, understaffed 1930s and 1940s and the overburdened, expansive later 1950s and 1960s. He was a splendid example of his generation of encyclopaedically learned teachers: he lectured at various times on Economics, English Literature, Economic History, Australian History and most periods of modern European and British History. By a singular set of circumstances, from the outset of his career La Nauze was acting head or head of his department in an era when god-professors carried heavy administrative and civic responsibilities. He disliked administration and academic politics, but his innate suspicion of vice-chancellors and bursars coupled with his dutiful devilling at papers made him a good in! fighter. He could be acerbic with colleagues and he was an aloof, impatient teacher of undergraduates, but he was scrupulous in his dealings with them and he was a model of what austere, dedicated scholarship could be. Privately, he was fiercely supportive of his juniors, many of whom owe their start to his exertions, not least his rigorous criticisms of their drafts. -

The Boy from Boort: Remembering Hank Nelson

The Boy from Boort The Boy from Boort Remembering Hank Nelson Edited by Bill Gammage, Brij V. Lal, Gavan Daws Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Gammage, Bill, 1942- author. Title: The boy from Boort : remembering Hank Nelson / Bill Gammage, Brij V. Lal, Gavan Daws. ISBN: 9781925021646 (paperback) 9781925021653 (ebook) Subjects: Nelson, Hank, 1937-2012. Historians--Australia--Biography. Military historians--Australia--Biography. College teachers--Australia--Biography. Papua New Guinea--Historiography. Other Authors/Contributors: Lal, Brij V., author. Daws, Gavan, author. Dewey Number: 994.007202 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Preface . vii Hyland Neil (‘Hank’) Nelson . ix Part I: Appreciation 1 . Farm Boys . 3 John Nelson 2 . The Boy from Boort . 5 Bill Gammage 3 . Talk and Chalk . 15 Ken Inglis 4 . Boort and Beyond . 19 Gavan Daws 5 . ‘I Don’t Think I Deserve a Pension – We Didn’t Do Much Fighting’: Interviewing Australian Prisoners of War of the Japanese, 1942–1945 . 33 Tim Bowden 6 . Doktorvater . 47 Klaus Neumann 7 . Hank, My Mentor . 55 Keiko Tamura 8 . Papua New Guinea Wantok . 63 Margaret Reeson 9 . -

Australian Journal of Biography and History: No. 1, 2018

Contents ARTICLES Australian historians and biography 3 Malcolm Allbrook and Melanie Nolan The Lady Principal, Miss Annie Hughston (1859–1943) 23 Mary Lush, Elisabeth Christensen, Prudence Gill and Elizabeth Roberts Nancy Atkinson, bacteriologist, winemaker and writer 59 Emma McEwin Andruana Ann Jean Jimmy: A Mapoon leader’s struggle to regain a homeland 79 Geoff Wharton Upstaged! Eunice Hanger and Shakespeare in Australia 93 Sophie Scott-Brown Frederick Dalton (1815–80): Uncovering a life in gold 113 Brendan Dalton Australian legal dynasties: The Stephens and the Streets 141 Karen Fox Jungle stories from ‘Dok’ Kostermans (1906–94), prisoner of war on the Burma–Thailand railway 151 Michèle Constance Horne Chinese in the Australian Dictionary of Biography and in Australia 171 Tiping Su BOOK REVIEWS Michelle Grattan review of Tom Frame (ed.), The Ascent to Power, 1996: The Howard Government 183 Ragbir Bathal review of Peter Robertson, Radio Astronomer: John Bolton and a New Window on the Universe 189 Darryl Bennet review of Peter Monteath, Escape Artist: The Incredible Second World War of Johnny Peck 191 Barbara Dawson review of Stephen Foster, Zoffany’s Daughter: Love and Treachery on a Small Island 197 Nichola Garvey review of Kerrie Davies, A Wife’s Heart: The Untold Story of Bertha and Henry Lawson 201 Les Hetherington review of Eric Berti (conceived and introduced) and Ivan Barki (ed.), French Lives in Australia: A Collection of Biographical Essays 205 Juliette Peers review of Deborah Beck, Rayner Hoff: The Life of a Sculptor 211 Stephen Wilks review of John Murphy, Evatt: A Life 217 Notes on contributors 223 Australian Journal of Biography and History is published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is available online at press.anu.edu.au ISSN 2209-9522 (print) ISSN 2209-9573 (online) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). -

Light That Time Has Made

LIGHTthat TIME has MADE Paul HASLUCK LIGHT THAT TIME HAS MADE by PAUL HASLUCK with an introduction and postscript by Nicholas Hasluck National Library of Australia 1995 Cover: Sir Paul Hasluck, Sydney, 1990 Photograph by Peter Rae; reproduced courtesy of Fairfax Photo Library © Nicholas Hasluck National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Hasluck, Paul, Sir, 1905-1993. Light that time has made. ISBN 0 642 10652 5. 1. Australians—Attitudes. 2. Public opinion—Australia. 3. Politicians—Australia—Biography. 4. Australia—Social conditions—20th century. 5. Australia—Politics and government—20th century. 6. Australia—History—20th century. 1. Hasluck, Nicholas, 1942- . II. National Library of Australia. III. Title. 994.04 Publisher's editor: Julie Stokes Designer: Andrew Rankine Printed by Goanna Print, Canberra CONTENTS Introduction by Nicholas Hasluck v BOOK I AUSTRALIA THEN AND NOW 2 Goggling 7 Gambling 13 Talking 19 Privacy Thrift 28 Universities 32 The Public Service 40 Aborigines 47 Heritage 53 Religion 57 The Nation State 62 National Identity 64 Tomorrow 71 History 78 iii BOOK 2 REFLECTIONS Walter Murdoch 86 The Rebel Judge 90 Kings' Men 95 The Casey/Bruce Letters 98 Intellectuals in Politics 105 P.R. 'Inky' Stephensen 109 Douglas Stewart 114 John Curtin 116 H.V. Evatt 121 Robert Menzies 134 Bunting's View 138 The Howson Diaries 143 The Gorton Experiment 146 The Whitlam Government 159 Foreign Affairs 165 Aboriginal Australians 170 Republican Pie 175 Tangled in the Harness 182 POSTSCRIPT by Nicholas Hasluck Postscript 191 Paul Hasluck—A Farewell Message 193 The Garter Box Goes Back to England 198 Alexandra Hasluck 212 IV INTRODUCTION y father, Sir Paul Hasluck (1905-1993), died at the age of 87 after a long Mcareer in public life, and having had an even longer innings as a writer. -

LETTERS from the WEST 1975-1976 David Carment

LETTERS FROM THE WEST 1975-1976 David Carment 1 Copyright David Carment 2015 First published in 2015 by David Carment, 11 Fairfax Road, Mosman NSW 2088, Australia, email [email protected], telephone 0299699103, http://www.dcarment.com ISBN: 978-0-646-94538-5 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Unless otherwise indicated all images belong to the author. 2 CONTENTS PREFACE 4 1975 7 1976 57 EPILOGUE 94 INDEX OF NAMES 95 3 PREFACE This is an edited collection of the letters I wrote to my parents while I worked in the Department of History at The University of Western Australia (UWA) in Perth between February 1975 and December 1976.1 It was my first full-time academic appointment. Although I was only in the job for less than two years, it and my residence in Currie Hall at the university significantly shaped my later life. The letters were usually hastily written, were far from comprehensive in describing my activities and now often seem clumsy and naïve. They provide, however, a young historian’s impressions of Australian academic life, an immigrant’s responses to Western Australia and a flavour of cultural, social and political developments during the mid 1970s. I was born in Sydney in 1949 into a middle class family of mainly Scottish ancestry. I graduated as a Bachelor of Arts (BA) with Honours in History at The University of New South Wales (UNSW) in 1972 and as a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History at The Australian National University (ANU) in 1975. My PhD thesis was on the Australian non-Labor federal politician Sir Littleton Groom (1867- 1936). -

The Phoenix Magazine and Australian Modernism Cheryl Hoskin

“A Genius About the Place”: The Phoenix Magazine and Australian modernism Cheryl Hoskin Originally presented as a History Festival exhibition, University of Adelaide Library, May 2013. If it is possible at this time still to feel the importance of poetry, Adelaide is now in an interesting condition. There are signs here that the imagination is stirring, and that if it has a chance it will give us something of our own. There is a genius about the place; and genius as a neighbour is exciting even at this dreadful moment. (C.R. Jury, Angry Penguins 1940) The literary, particularly poetic, upsurge wrought by the Angry Penguins journal began in 1935 with Phoenix, centred at the University of Adelaide. The decision of the editors to change the ‘jolly old school magazine’ format of the Adelaide University Magazine to a completely literary journal started a seminal period in Australia’s cultural history. Phoenix published works ranging from the nationalistic poetry of Rex Ingamells and the Jindyworobaks Club to the avant-garde modernist verse of Max Harris, D.B. Kerr and Paul Pfeiffer, with art by John Dowie and Dorrit Black, among others. During 1940, in reaction to withdrawal of funding for Phoenix, Harris, Kerr, Pfeiffer and Geoffrey Dutton founded the influential Angry Penguins magazine which sought to promote internationalism and ‘a noisy and aggressive revolutionary modernism’ to Australian culture. Why did the relatively conservative University of Adelaide become the ‘literary hotbed’ of Australian modernism? A faculty of some distinction, the creative support of Professors C.R. Jury and J.I.M. Stewart, a University Union which encouraged student participation and debate though the Arts Association and the student newspaper On Dit, the modern literature available through the newly built Barr Smith Library and Preece’s Bookshop, and the collegiality of St Mark’s College all played a role.