2. Sir Keith Hancock: Laying the Foundations, 1959–1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 AFANADOR, Ruven. Torero. with an Introduction by Hector Abad Faciolince

1 AFANADOR, Ruven. Torero. With an introduction by Hector Abad Faciolince. Poems by Gloria Maria Pardo Vargas. (Thalwil/Zurich and New York): Edition Stemmle, (2001). Large 4to. Orig. boards. Dustjacket. Unpaginated. Copiously illustrated with full-page b/w photographic images, and text-illusts. Title-page printed in orange and black ink. Fine. $150 2 AMIS, Kingsley. The James Bond Dossier. London: Cape, (1965). 8vo. Orig. black cloth with blind-stamped stylised “007” on front cover. Spine gilt. Dustjacket designed by Jan Pienkowski, based on Richard Chopping’s famous trompe l’oeil Bond dustjackets. (160pp.). 1st ed. Tabular reference guide to the Bond novels at end. Some light foxing to endpapers, otherwise fine. $125 3 ANDERSON, D.G. Australia’s Contribution to the Development of International Civil Aviation. (Being) the Second Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith Memorial Lecture delivered to the Adelaide Branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society - Australian Division. (Adelaide April 1960). 4to. Orig. printed wrapper. Unpaginated. Illustrated. Text printed in double-column. Ex-library copy. $50 4 ANGAS, George French. Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand: Being an Artist’s impressions of Countries and People at the Antipodes. 2 vols. London 1847. (Facs. Adelaide 1969). 8vo. Orig.cloth. With col. frontispiece, title-vignettes, 12 full-page plates, and text-illusts. (Aust. Facsimile Editions, No. 184). Fine. The original prospectus loosely inserted. $100 5 ARNOLD, Matthew. The Scholar Gipsy & Thyrsis. London: Phillip Lee Warner, 1910. Large 4to. Orig. full gilt-illust. vellum with bevelled boards. Spine gilt titled. T.e.g. other edges uncut. (x, 68pp.). -

Artistic Identity in the Published Writings of Margaret Thomas (C1840-1929)

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1993 Artistic identity in the published writings of Margaret Thomas (c1840-1929) Lynn Patricia Brunet University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Brunet, Lynn Patricia, Artistic identity in the published writings of Margaret Thomas (c1840-1929), Master of Creative Arts (Hons.) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1993. -

04 Lists and Tables

INDEX, PAOB Academic Dress 309 Academic Year 92 Accounts. Statement of .. 68* Admission ad Eundem 43, 4, 10, 12 Admission Without Examination .. 41, 43 Agricultural College, Dookie 262 Agriculture Details of Subjects.. „ B72 Diploma of( Regulation .. 258 Diplomates in, proceeding to B.Agr.Sc. .. 260 Agricultural Science Degree of Bachelor of, Regulation 2(1 Degree of Mastef of, Regulation .. 261 Permission to Divide Years 118 Proceeding to Engineering.. 209, 216, 222, 228 Ambulance Class.. .. .. 666 Analytical Chemistry (see Chemistry) Announcements .. .. .. 633 Annual Examinations Admission to Supplementary 116, 120 Certificates .. 125 Details of Subjects and Text Books .. 36, 433 Entry and Fees 111 Examiners 28 Medical Course .. 158 Military Duties .. .. .. 122 Passing and Completing Years 116 Publication of Results .. 124 Subjects .. .. 110 Times and Conduct .. 106 Animal Report .. 651 Appointments Board 70 Architecture. Diploma in, Regulation .. 236 Army Commissions .. .. *. .. 641 Articled Clerks .. 644 IV. INDKX. PlOX Arts, Bachelor of Details of Subjects 433 Proceeding to Engineering .. 209, 216, 222, 228, 274 Proceeding to Medicine .. 272 Proceeding to Science .. 274 Leave to take two Subjects.. 116, 462, 634 Regulation .. .. 181 Arts, Degree of Master of Details of Subjects .. 469 Regulation .. .. 137 Attendants and Assistants 32 Australian College of Dentistry .. .. .. 873 Statute .. 68 Barristers. Admission of .. .; .. 6*4 • Benefactions. List of .. 647 Boards, Faculties, etc.. Lists of .. xxvi. British School at Rome .. 642 Calendar—Date of Publication and Contents.. 35 Candidates for Degrees and Diplomas, Statote .. 38 Certificated Teachers 126, 127, 128 Certificates ' Annual Examinations • .. Matriculation Public'Examinations . Lectures .. • .. 106 Changing Courses 121,141,209,216, 222, 228, 272 Chemistry, Diploma of Analytical Details of Subjects 490 Regulation . -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

HIST 80000: Literature of Modern Europe I (Draft) CUNY Graduate

HIST 80000: Literature of Modern Europe I (Draft) CUNY Graduate Center, Wednesday, 4:15-6:15 p.m., 5 credits Professor David G. Troyansky Office 5104. Hours: 3:00-4:00 p.m., Wednesday, and by appointment. Direct line: 212 817-8453. Most of the week at Brooklyn College: 718 951-5303. E-mail: [email protected] This course is designed to introduce first-year students to some of the major debates and recent (and sometimes classic) books in European history from the 1750s to the 1870s. It is also intended to help prepare students for the First (Written) Examination. Objectives: By the end of the course, students should be able to demonstrate familiarity with many of the central historiographical issues in the period and to assess historical writings in terms of approach, use of sources, and argument. They should be able to draw on multiple works to make larger arguments concerning major problems in European history. Requirements: Each week, students will come to class prepared to discuss assigned readings. They include common readings and individual works chosen from the supplementary lists. In anticipation of the next day’s class, by early Tuesday evening, students will have submitted by email to the instructor and to the rest of the class a two-to-three-page (double-spaced) paper on their week’s readings. Eleven papers must be submitted; two weeks may be skipped, but even then everyone is expected to be prepared for discussion. The papers should not simply summarize. They should explain and compare the theses of the assigned books; describe the authors’ methods, arguments, and sources; and assess their persuasiveness, significance, and implications. -

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

Essay Reviews

Essay Reviews DEATH AND THE DOCTORS PHILIPPE ARIES, The hour ofour death, London, Allen Lane, 1981, 8vo, pp. xxii, 652, illus., £14.95. ROBERT CHAPMAN, IAN KINNES, and KLAUS RANDSBORG (editors), The archaeology ofdeath, Cambridge University Press, 1981, 4to, pp. 158, illus., £17.50. JOHN McMANNERS, Death and the Enlightenment. Changing attitudes to death among Christians and unbelievers in eighteenth-century France,'Oxford University Press, 1981, 8vo, pp. vii, 619, £17.50. JOACHIM WHALEY (editor), Mirrors ofmortality. Studies in the social history of death, London, Europa, 1981, pp. vii, 252, £19.50. There is no more universal social fact than death ("never send to know for whom the bell tolls"). Yet death is the topic supremely difficult for historians to research, since, though all live under its shadow, none has experienced it directly for himself, and there are no scientific tests of its most momentous putative consequence, an afterlife, for which men have slain and been slain. It is, nevertheless, a fashionable subject of inquiry, gaining 6clat first in France, and now, like so many other Paris fas- hions, being exported to Britain and across the Atlantic. One can chronicle death at the most metaphysical level (as in Norman 0. Brown's Life against Death (1959), a Freudian psychohistory of mankind, viewing civilization as a holding operation, keeping death at bay, a bid on immortality), or in the most personal terms, as in Victor and Rosemary Zorza's Kindertotenbuch, A way ofdying (1980), which offers a moving account of the agonies of coming to terms with the departure of a loved one. -

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat Greg Young This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Education and Arts Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Ballarat 3353 Victoria, Australia STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Except where explicit reference is made in the text this thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree of diploma. No other person’s work has been relied upon or used without due acknowledgement in the main text and bibliography. Signed (Applicant): Date: Signed (Supervisor): Date: When the intellectual and spiritual history of the nineteenth century comes to be written, a highly interesting chapter in it will be that which records the origin, growth, decline, and disappearance of the delusion of spiritualism. —Australasian Saturday 25 October 1879 Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to my University of Ballarat (now Federation University) supervisors Dr Anne Beggs Sunter, Dr Jill Blee, and Dr David Waldron for their encouragement, advice, and criticism. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge a large debt of gratitude to Professor Tony Milner and Professor John Powers, both of the Australian National University, for their generous support. This project began in the Heritage Library of the Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute; I am grateful to the BMI for its friendly help. Dedication To Anne, Peter, Charlotte, and my teacher Dr Rafe de Crespigny. Abstract This thesis is about the origins, growth, and decline of spiritualism in nine- teenth-century Ballarat. -

HISTORY of CHRISTIANITY II February-April 2019: Reformed Theological Seminary, Atlanta ______Professor: Ken Stewart, Ph.D

1 HISTORY OF CHRISTIANITY II February-April 2019: Reformed Theological Seminary, Atlanta ___________________________________________________ Professor: Ken Stewart, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Phone: 706.419.1653 (w); 423.414.3752 (cell) Course number: 04HT504 Class Dates: Friday evening 7:00-9:00 pm and Saturday 8:30-5:30 p.m. February 1&2, March 1&2, March 29&30, April 26&27 Catalog Course Description: A continuation of HT502, concentrating on great leaders of the church in the modern period of church history from the Reformation to the nineteenth century. Course Objectives: To grasp the flow of Christian history in the western world since 1500 A.D., its interchange with the non-western world in light of transoceanic exploration and the challenges faced through the division of Christendom at the Reformation, the rise of Enlightenment ideas, the advance of secularization and the eventual challenge offered to the dominance of Europe. To gain the ability to speak and write insightfully regarding the interpretation of this history and the application of its lessons to modern Christianity Course Texts (3): Henry Bettenson & Chris Maunder, eds. Documents of the Christian Church 4th Edition, (Oxford, 2011) Be sure to obtain the 4th edition as documents will be identified by page no. Justo Gonzáles, The Story of Christianity Vol. II, 2nd edition (HarperOne, 2010) insist on 2nd ed. Kenneth J. Stewart, Ten Myths about Calvinism (InterVarsity, 2011) [Economical used editions of all titles are available from the following: amazon.com; abebooks.com; betterworldbooks.com; thriftbooks.com] The instructor also recommends (but does not require), Tim Dowley, ed. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

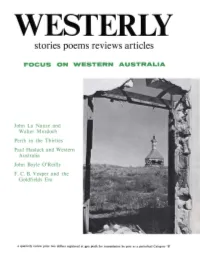

Stories Poems Reviews Articles

ESTERLY stories poems reviews articles FOCUS ON WESTERN AUSTRALIA John La Nauze and Walter Murdoch Perth in the Thirties Paul Hasluck and Western Australia John Boyle O'Reilly F. C. B. Vosper and the Goldfields Era a quarterly review price two dollars registered at gpo perth for transmission by post as a periodical Category '8 ' UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PRESS Giving the widest representation to Western Australian writers E. J. STORMON: The Salvado Memoirs $13.95 MARY ALBERTUS BAIN: Ancient Landmarks: A Social and Economic History of the Victoria District of Western Australia 1839-1894 $12.00 G. C. BOLTON: A Fine Country to Starve In $11.00 MERLE BIGNELL: The Fruit of the Country: A History of the Shire of Gnowangerup, Western Australia $12.50 R. A. FORSYTH: The Lost Pattern: Essays on the Emergent City Sensibility in Victorian England $13.60 L. BURROWS: Browning the Poet: An Introductory Study $8.25 T. GIBBONS: Rooms in the Darwin Hotel: Studies in English Literary Criticism and Ideas 1880-1920 $8.95 DOROTHY HEWETT, ED.: Sandgropers: A Western Australian Anthology $6.25 ALEC KING: The Un prosaic Imagination: Essays and Lectures on the Study of Literature $8.95 AVAILABLE ALL GOOD BOOKSELLERS Forthcoming Publications Will Include: MERAB T AUMAN: The Chief: Charles Yelverton O'Connor IAN ELLIOT: Moondyne Joe: The Man and the Myth J. E. THOMAS & Imprisonment in Western Australia: Evolution, Theory A. STEWART: and Practice The prices set out are recommended prices only. Eastern States Agents: Melbourne University Press, P.O. Box 278, Carlton South, Victoria, 3053. WESTERLY a quarterly review EDITORS: Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan EDITORIAL ADVISORS: Patrick Hutchings, Leonard Jolley, Margot Luke, Fay Zwicky Westerly is published quarterly by the English Department, University of Western Australia, with assistance from the Literature Board of' the Australia Council and the Western Australian Literary Fund.