Margaret Kiddle: the Writing of Men of Yesterday and the Melbourne School of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

The Patrician and the Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the Making of Australian History

128 New Zealand Journal of History, 42, 1 (2008) The Patrician and the Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the Making of Australian History. By John Thompson. Pandanus Books, Canberra, 2006. xix, 383pp. Australian price: $34.95. ISBN 1-74076-152-9. THE LIKELY INTEREST FOR READERS OF THIS JOURNAL in this book is that Geoffrey Serle (1922–1998) helped to pioneer Australian historiography in much the way that Keith Sinclair prompted and promoted a ‘nationalist’ New Zealand historiography. Rather than submitting to the cultural cringe and seeing their respective countries’ pasts in imperial and British contexts, Serle and Sinclair treated them as histories in their own right. Brought up in Melbourne, Serle was a Rhodes Scholar who returned to the University of Melbourne in 1950 to teach Australian history following the departure of Manning Clark to Canberra University College. The flamboyant Clark is generally seen as the father of Australian historiography and Serle has been somewhat cast in his shadow. Yet Serle’s contribution to Australian historiography was arguably more solid. As well as undergraduate teaching, postgraduate supervision and his writing there was the institutional work: his efforts on behalf of the proper preservation and administration of public archives, his support of libraries and art galleries, the long-term editorship of Historical Studies (1955–1963), and co-editorship then sole editorship of the Australian Dictionary of Biography (1975–1988). Clark was a creative spirit, turbulent and in the public gaze. The unassuming Serle was far more oriented towards the discipline. The book’s title derives from ‘the streak of elitism in Geoffrey Serle sitting in apparent contradiction with himself as “ordinary” Australian, easygoing, democratic, laconic’ (p.9, see also p.303, n.40). -

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat Greg Young This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Education and Arts Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Ballarat 3353 Victoria, Australia STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Except where explicit reference is made in the text this thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree of diploma. No other person’s work has been relied upon or used without due acknowledgement in the main text and bibliography. Signed (Applicant): Date: Signed (Supervisor): Date: When the intellectual and spiritual history of the nineteenth century comes to be written, a highly interesting chapter in it will be that which records the origin, growth, decline, and disappearance of the delusion of spiritualism. —Australasian Saturday 25 October 1879 Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to my University of Ballarat (now Federation University) supervisors Dr Anne Beggs Sunter, Dr Jill Blee, and Dr David Waldron for their encouragement, advice, and criticism. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge a large debt of gratitude to Professor Tony Milner and Professor John Powers, both of the Australian National University, for their generous support. This project began in the Heritage Library of the Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute; I am grateful to the BMI for its friendly help. Dedication To Anne, Peter, Charlotte, and my teacher Dr Rafe de Crespigny. Abstract This thesis is about the origins, growth, and decline of spiritualism in nine- teenth-century Ballarat. -

The University Tea Room: Informal Public Spaces As Ideas Incubators Claire Wright University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2018 The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators Claire Wright University of Wollongong, [email protected] Simon Ville University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Wright, C. & Ville, S. (2018). The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators. History Australia, 15 (2), 236-254. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators Abstract Informal spaces encourage the meeting of minds and the sharing of ideas. They es rve as an important counterpoint to the formal, silo-like structures of the modern organisation, encouraging social bonds and discussion across departmental lines. We address the role of one such institution – the university tea room – in Australia in the post-WWII decades. Drawing on a series of oral history interviews with economic historians, we examine the nature of the tea room space, demonstrate its effects on research within universities, and analyse the causes and implications of its decline in recent decades. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Wright, C. & Ville, S. (2018). The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators. History Australia, 15 (2), 236-254. This journal article is available at Research -

T'the Phoenix Has Now Risen from Its Ashes

THE ACADEMY & THE HUMANITIES IN 19691 » Graeme DAVison ‘The Phoenix has now risen from its ashes, Seventy-one year old Hancock and a lovelier bird and — what matters more — a seventy-five year old Menzies were near- Tlivelier one’, the inaugural president of the contemporaries, having both arrived at the Australian Academy of the Humanities, Sir University of Melbourne as scholarship boys Keith Hancock, wrote exultantly to its political in the years around World War One. Each patron, Sir Robert Menzies, at the end of man, in his way, had been imbued with ideals September 1969. ‘We have not only a new name of academic and public service through their but a new infusion of creative vigour’.2 Since studies under the university’s influential the foundation of the Australian Humanities Professor of Law, Harrison Moore.3 Both were Research Council (AHRC) in 1955, its founders products of the liberal imperialism of their era, had anticipated its transformation, in due Hancock becoming the pre-eminent historian course, into an Academy of Letters or, as it of the British Empire, and Menzies one of 'THE PHOENIX HAS NOW RISEN FROM ITS ASHES, A LOVELIER BIRD AND — WHat MattERS MORe — A LIVELIER ONE' — sIR KEITH HANCOCK IN A LEttER TO SIR ROBERT MENZIES, 1969. turned out, an Academy of the Humanities. its most devoted political servants. While The plumage of the new bird, with its royal Hancock had won academic laurels in Oxford charter and crest, was certainly more glorious and London, returning to his homeland only than that of the old AHRC, but the bird itself towards the end of his career, Menzies had was remarkably like the old one. -

Serle Austerica Unlimited

GODZONE: 6) AUSTERICA UNLIMITED? GEOFFREY SERLE WE HAVE COME a long way in the last thirty years, Growing up in the 19305 . Loyalty to Empire was still the un challengeable emphasis of school and society. History was English and Imperial History, a little European; Australia (and America) were only mentioned as part of the imperial story. English was entirely English literature, of course. (And at home we read Pooh BeaT~ Peter Pan and Alice, Kipling, Rider Haggard and G. A. Henty, Chums, the Boys' Own Paper, Champion and Magnet.) The newspapers were still chock-Cull of English and European news. On Anzac Day fire-eating generals would indeed tell us that Australia became a nation at Gallipoli, but went on to dwell on the glories of the Empire of which Australia was only a subordi nate part and the inherent superiority of the Britisher over any other 'race'. (At the famous Presbyterian Scottish academy which I attended, the high· spot of the Anzac Day ceremony-can I be remembering oorrectly?-was the song 'For England' written in 1914-'England, Oh England, and how could I stay?). The blurred double loyally characterized the great majority of Australians: at the State schools it was laid down that the flag to be saluted on Monday mornings could be either the Australian or the Union Jack. But while many Australians, especially those of working-class or Irish origin, had developed a limited sense of Aus tralianness, ruling orthodoxy between the wars-partly in reaction to recognition of incipient subversive nationalism-put all the stress on Empire; there may have been more coherent and systematic indoctrina tion in the schools in this period than at any other time in Australian history. -

A History of Manning Clark the Making of Manning Clark

The making of Manning Clark This is the Published version of the following publication Pascoe, Robert (1978) The making of Manning Clark. The National Times : Australia's national weekly of business and affairs (382). pp. 18-23. The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/19397/ 1 A HISTORY OF MANNING CLARK (cover story, The National Times, week ending 2 June 1978, pp. 18-23) THE MAKING OF MANNING CLARK By ROB PASCOE Early one morning in November, 1938, a 23-year-old history student got out of the train at Bonn Railway Station. Manning Clark was fresh out of the University of Melbourne, full of socialist and Freudian ideas about what was wrong with the world and how it should be improved. The night before he alighted at that station roving gangs of Nazi stormtroopers had smashed up every Jewish business house in Bonn and elsewhere in Germany. Clark made his way amid the debris throughout Bonn in a state of disbelief. “That was the beginning of an awakening”, he recalled recently. “That was the moment when I realised that I would have to start to think again about the whole human situation.” Clark was born the second son of an Anglican clergyman in Sydney in March 1915. His parents named him Charles Manning Hope Clark, a resounding enough emblem of this ecclesiastical background. An uncle and an older brother followed this clerical tradition, but Clark decided at a young age that God’s emissaries in Australia had either misunderstood the religious needs of the people or were misrepresenting what there was to know and preach about man, his relations with others, and nature. -

7. the Road to Conlon's Circus—And Beyond

7. The Road to Conlon’s Circus—and Beyond: A personal retrospective J . D . Legge I was still a schoolboy when World War II broke out in September 1939. The son of a Presbyterian Minister in a small town to the north of Warrnambool, Victoria, I did most of my secondary schooling at Warrnambool High. After matriculating there, I went on to Geelong College to complete two years of ‘Leaving Honours’ as a preparation for university studies. From there, I had observed the Munich Agreement, the Anschluss, the Czechoslovakia crisis, the German–Soviet agreement of August 1939, and the German invasion of Poland, all leading up to the final outbreak of war. To an Australian schoolboy in his late teens, these events seemed to be essentially European affairs—indeed the war itself appeared almost as a continuation of World War I, and there seemed no reason why I should not embark, as planned, on a university course. I enrolled at the University of Melbourne in what, in retrospect, seem the golden days of R. M. Crawford’s School of History.1 The emphasis was largely on European and British history: Crawford’s modern history course dealing especially with the Renaissance and Reformation, Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s course on Tudors and Stuarts, the Civil War, and the Protectorate and the Restoration, and Jessie Webb’s ancient history course. This perspective followed naturally from the courses offered in Victorian secondary schooling of the day, leading on to university studies. There too we had studied British history from 1066 to 1914, European history from 1453 to 1848, and accompanying courses in English literature (including four or five plays of Shakespeare between years 9 and 11), English poetry from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, and a foreign language—usually French or German. -

Max Crawford RAYMOND MAXWELL CRAWFORD 1906 - 1991

Max Crawford RAYMOND MAXWELL CRAWFORD 1906 - 1991 Max Crawford, a Foundation Fellow, died in Melbourne on 24 November 1991. He prefaced his 1939 'synoptic view' of The Study of History with Maitland's dictum that 'all history is but a seamless web'. It now furnishes a fitting epitaph to his achievement in transforming the study of history. Through his role while Professor of History at the University of Melbourne between 1937 and 1970, Crawford's stature in Australian intellectual history is secure. He elevated the contribution of history by his imaginative leadership in stimulating his staff and students to rewrite the past, and to assist positively in reshaping Australian national life and culture. Raymond Maxwell Crawford was born at Grenfell, NSW, on 6 August 1906, the ninth of twelve children of a self improving coalminer and railwayman and his resourceful wife. Max reflected upon family circumstances when describing 'my brother Jack' (Sir John, the distinguished economist), and recalled that, during their youth, 'we were familiar with thrift, but did not know hardship'. The Presbyterian ambience of their home, where 'the Church was our club', ensured that, in their maturity, although church doctrine might be discarded, 'its values were ingrained'. Crawford's gentle, gracious, but forthright character, his interest in civil liberties, his eloquence, and his vision of the moral value of history, probably owed much to those influences. Educated at Sydney Boys' High School and the University of Sydney, Crawford proceeded to Balliol College on a scholarship. He emerged with a deep appreciation of literature and he proved an adept painter, so that his later university interests spanned these disciplines by facilitating combined honours courses involving History, and English, Fine Art or Philosophy, respectively. -

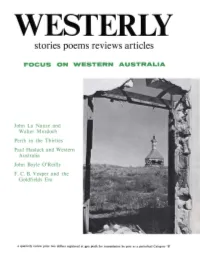

Stories Poems Reviews Articles

ESTERLY stories poems reviews articles FOCUS ON WESTERN AUSTRALIA John La Nauze and Walter Murdoch Perth in the Thirties Paul Hasluck and Western Australia John Boyle O'Reilly F. C. B. Vosper and the Goldfields Era a quarterly review price two dollars registered at gpo perth for transmission by post as a periodical Category '8 ' UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PRESS Giving the widest representation to Western Australian writers E. J. STORMON: The Salvado Memoirs $13.95 MARY ALBERTUS BAIN: Ancient Landmarks: A Social and Economic History of the Victoria District of Western Australia 1839-1894 $12.00 G. C. BOLTON: A Fine Country to Starve In $11.00 MERLE BIGNELL: The Fruit of the Country: A History of the Shire of Gnowangerup, Western Australia $12.50 R. A. FORSYTH: The Lost Pattern: Essays on the Emergent City Sensibility in Victorian England $13.60 L. BURROWS: Browning the Poet: An Introductory Study $8.25 T. GIBBONS: Rooms in the Darwin Hotel: Studies in English Literary Criticism and Ideas 1880-1920 $8.95 DOROTHY HEWETT, ED.: Sandgropers: A Western Australian Anthology $6.25 ALEC KING: The Un prosaic Imagination: Essays and Lectures on the Study of Literature $8.95 AVAILABLE ALL GOOD BOOKSELLERS Forthcoming Publications Will Include: MERAB T AUMAN: The Chief: Charles Yelverton O'Connor IAN ELLIOT: Moondyne Joe: The Man and the Myth J. E. THOMAS & Imprisonment in Western Australia: Evolution, Theory A. STEWART: and Practice The prices set out are recommended prices only. Eastern States Agents: Melbourne University Press, P.O. Box 278, Carlton South, Victoria, 3053. WESTERLY a quarterly review EDITORS: Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan EDITORIAL ADVISORS: Patrick Hutchings, Leonard Jolley, Margot Luke, Fay Zwicky Westerly is published quarterly by the English Department, University of Western Australia, with assistance from the Literature Board of' the Australia Council and the Western Australian Literary Fund. -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5.