HBO's Chernobyl and Climate Change Denial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 9: Why We Fight

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 9: Why We Fight INTRO: Band of Brothers is a ten-part video series dramatizing the history of one company of American paratroopers in World War Two—E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne, known as “Easy Company.” Although the company’s first experience in real combat did not come until June 1944 ( D-Day), this exemplary group fought in some of the war’s most harrowing battles. Band of Brothers depicts not only the heroism of their exploits but also the extraordinary bond among men formed in the crucible of war. In the ninth episode, Easy Company finally enters Germany in April 1945, finding very little resistance as they proceed. There they are impressed by the industriousness of the defeated locals and gain respect for their humanity. But the G.I.s are then confronted with the horror of an abandoned Nazi concentration camp in the woods, which the locals claim not to have known anything about. Here the story of Easy Company is connected with the broader narrative of the war—the ideology of the Third Reich and Hitler’s plan to exterminate the Jews. CURRICULUM LINKS: Band of Brothers can be used in history classes. NOTE TO EDUCATORS: Band of Brothers is appropriate as a supplement to units on World War Two, not as a substitute for material providing a more general explanation of the war’s causes, effects, and greater historical significance. As with war itself, it contains graphic violence and language; it is not for the squeamish. Mature senior high school students, however, will find in it a powerful evocation of the challenges of war and the experience of U.S. -

Madonna's Music Videos Defined the MTV Era And

Strike a Pose Madonna’s music videos defined the MTV era and changed pop culture forever. Here are the stories behind the 20 greatest SOUND AND VISION Madonna in the “Vogue” video, 1990 00 72 | MADONNA | COLLECTORS EDITION COLLECTORS EDITION | MADONNA | 00 Ray of Light 1998 A bold embrace of electronica that got Madonna her due at the VMAs “it’s probably, to this day, No. 1 the longest shoot ever for a 2 music video,” remembers direc- tor Jonas Åkerlund, who traveled to New York, Los Angeles and Las Vegas to get “Ray of Light” ’s fast-forward cut- and-paste look. The clip had a simi- Express lar feel to the 1982 art-house favorite Koyaanisqatsi (which Åkerlund had never seen) and a frantic energy that fit the song’s embrace of “electronica.” “We had this diagram that I had in Yourself my pocket for the whole production,” 1989 Åkerlund recalls. “Let’s say you shoot Taking total control of the one frame every 10 seconds or so. Then artistic process, Madonna you have to do that for 30 minutes to worked with director David get like five seconds. Every shot was Fincher to make a sci-fi classic just, like, such a big deal.” The hard work paid off: Although she made near- ly 70 music videos during her career, “Ray of Light” is the only one to win he first of an MTV Video Music Award for Video The VMA- Madonna’s col- of the Year. Says Åkerlund, “I didn’t winning “Ray laborations with of Light” video really think about winning the VMAs. -

Huron University College Department of English English 2550F: Heroes

Huron University College Department of English English 2550F: Heroes and Superheroes Intersession 2021 Dr. Adrian Mioc Class: Tue 9:30 AM -12:30 PM, Th 9:30 AM - 12:30 PM Office: UC 3314 Office Hours: Thu 12:30-2:30 PM Email: [email protected] Prerequisite(s): At least 60% in 1.0 of English 1020-1999 or permission of the Department. Although this academic year might be different, Huron University is committed to a thriving campus. We encourage you to check out the Digital Student Experience website to manage your academics and well-being. Additionally, the following link provides available resources to support students on and off campus: https://www.uwo.ca/health/. Technical Requirements: Stable internet connection Laptop or computer Working microphone Working webcam General Course Description This course aims to explore the figure of the hero and superhero as it evolves and is depicted in contemporary comic books as well as in other forms of popular culture such as movies and TV series. Methodologically, it will combine the study of literature with contemporary popular culture while incorporating a theoretical component as well. Specific Focus: In the beginning, we will briefly explore myths that are relevant and will help us understand the figure of the modern day superhero. After a quick historical exploration, which will offer a substantial foundation for the study of the 20th and 21st-century manifestation of the superheroes, the main focus of this course will be placed on the problematic of this figure. Besides well-known characters (Superman, Batman and Spiderman), we will tackle less-spoken-about figures such as Jessica Jones or Harley Qinn. -

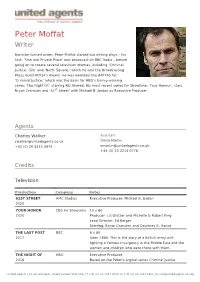

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Neuerwerbungen Noten

NEUERWERBUNGSLISTE OKTOBER 2019 FILM Cinemathek in der Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek © Eva Kietzmann, ZLB Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin Stiftung des öffentlichen Rechts Inhaltsverzeichnis Film 5 Stummfilme 3 Film 7 Fernsehserien 3 Film 10 Tonspielfilme 6 Film 20 Animationsfilme 24 Film 27 Animation/Anime Serien 24 Film 30 Experimentalfilme 24 Film 40 Dokumentarfilme 25 Musi Musikdarbietungen/ Musikvideos 25 K 400 Kinderfilme 26 Ju 400 Jugendfilme 38 Sachfilme nach Fachgebiet 42 Seite 2 von 48 Stand vom: 01.11.2019 Neuerwerbungen im Fachbereich Film Film 5 Stummfilme Film 5 Chap 1 ¬The¬ circus / Charles Chaplin [Regie Drehbuch Darst. Prod. a:BD Komp.]. Merna Kennedy [Darst.] ; Allan Garcia [Darst.] ; Harry Cro- cker [Darst.] ; Eric James [Musikberatung] ; Lambert Williamson [Musikarrangement] ; Charles D. Hall [Ausstattung]. - 2019 Film 5 Chap 1 ¬The¬ circus / Charles Chaplin [Regie Drehbuch Darst. Prod. c:DVD Komp.]. Merna Kennedy [Darst.] ; Allan Garcia [Darst.] ; Harry Cro- cker [Darst.] ; Eric James [Musikberatung] ; Lambert Williamson [Musikarrangement] ; Charles D. Hall [Ausstattung]. - 2019 Film 7 Fernsehserien Film 7 AgentsS Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. : [BD]. - 4. Staffel. ¬Die¬ komplette vierte 1:4.BD Staffel / Filmregisseur: Vincent Misiano ; Drehbuchautor: Stan Lee ; Komponist: Bear McCreary ; Kameramann: Feliks Parnell ; Schau- spieler: Clark Gregg, Ming-Na Wen ; Chloe Bennet, Iain de Caeste- cker [und weitere]. - 2019 Film 7 AgentsS 1 Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. : [DVD-Video]. - 4. Staffel, Episoden 1-22. a:4.DVD ¬Die¬ komplette vierte Staffel. - 2019 Film 7 AmerHor American Horror Story : [BD]. - 8. Staffel. Apocalypse : die kom- 1:8.BD plette achte Season / Filmregisseur: Bradley Buecker ; Drehbuch- autor: Brad Falchuk, Ryan Murphy ; Komponist: James S. -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders. -

TV Academy Honors ARRI ALEXA Camera System with Engineering Emmy®

Contact: An Tran Public Relations Manager + 1 818 841 7070 [email protected] Reegan Koester Corporate Communications Manager +49 89 3809 1768 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TV Academy Honors ARRI ALEXA Camera System with Engineering Emmy® • ARRI receives highest TV technology recognition for outstanding achievement in engineering development • Since 2010, ALEXA has been the camera system of choice on numerous television and feature productions • ALEXA’s digital technology has been embraced by the television industry for its stunning image quality, reliability, and ease October 26, 2017, Los Angeles – At the 69th Engineering Emmy® Awards Ceremony in Hollywood, the Television Academy recognized ARRI with the most prestigious television accolade for outstanding achievement in engineering development for its ALEXA digital motion picture camera system. On October 25, 2017, at the Loews Hollywood Hotel, actress Kirsten Vangsness, who presented the award, said: “The ALEXA camera system represents a transformative technology in television due to its excellent digital imaging capabilities coupled with a completely integrated postproduction workflow. In addition, a cohesive pipeline, the onboard recording of both raw and a compressed video image, and an easy-to-use interface contributed to the television industry’s widespread adoption of the ARRI ALEXA.” The Engineering Award was accepted by ARRI´s Harald Brendel, Teamlead Image Science, and Frank Zeidler, Senior Manager Technology and Deputy Head of R&D – both members of the ALEXA development team – as well as Glenn Kennel, President of ARRI Inc. In his acceptance speech, Harald Brendel mentioned ARRI’s 100-year legacy of laying the foundation for the ALEXA and keeping the camera today as the industry workhorse. -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations -

MEDIA RESOURCE NEWS Suffolk County Community College Libraries August 2014

MEDIA RESOURCE NEWS Suffolk County Community College Libraries August 2014 Ammerman Grant Eastern Rosalie Muccio Lynn McCloat Paul Turano 451-4189 851-6742 548-2542 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 8 Women/8 Femmes. A wealthy industrialist is found murdered in his home while his family gathers for the holiday season. The house is isolated and the phone lines have been found to be cut. Eight women are his potential murderers. Each is a suspect and each has a motive. Only one is guilty. In French with subtitles in English or Spanish and English captions for the hearing impaired. DVD 1051 (111 min.) Eastern A La Mar. "Jorge has only a few weeks before his five-year-old son Natan leaves to live with his mother in Rome. Intent on teaching Natan about their Mayan heritage, Jorge takes him to the pristine Chinchorro reef, and eases him into the rhythms of a fisherman's life. As the bond between father and son grows stronger, Natan learns to live in harmony with life above and below the surface of the sea."--Container. In Spanish, with optional English subtitles; closed-captioned in English. DVD 1059 (73 min.) Eastern Adored, The. "Maia is a struggling model. After suffering a major loss, her relationship with her husband is thrown into turmoil. She holds high hopes that a session with the prolific celebrity photographer, Francesca Allman, will rejuvenate her career and bring her out of her depression. However, Francesca suffers from severe OCD and has isolated herself in remote North West Wales in a house with an intriguing past. -

Films on the Holocaust

Films on the Holocaust Because the Holocaust was such a unique and painful event in the history of human interactions, many filmmakers have dealt with the subject in their films. As the topic is so large, filmmakers all over the world, from the 1940s to our day, have chosen to depict diverse aspects of the Holocaust in both fiction and nonfiction films. During the first years after World War II, fiction films about the Holocaust were made in those Eastern European countries that suffered very badly under the Nazis. In some of the films from that time, the Nazi persecution of Jews plays a minor role, while the war and the ensuing hardship take the films' major focus. An example of this phenomenon is the trilogy of films made by Polish director Andrzej Wajda, which describe Polish life in occupied Warsaw. Since that time, a number of films have been produced that focus on Jewish characters and the specifically Jewish experience during the Holocaust. The Diary of Anne Frank (1959) depicts a young Dutch girl who hid with her family for years until they were discovered by the Nazis (see also Frank Anne). Kapo (1960) hits on the compelling moral issues surrounding a Jewish labor foreman in a concentration camp. Jacob the Liar, first made in Germany in 1978 and remade in the United States in 1999, is the tale of a ghetto Jew who cheers his fellow Jews by telling them the lie that the Germans are losing the war. A different type of fictionalized Holocaust film is that which uses the Holocaust as a backdrop for the film's main story line, rather than a major focus.