Religious, Caste, Gender Inequalities and the Making of Akhāṛās

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling: Glory of India at the Olympics—A Brief History of Indian Wresting Team in the Olympic Games

Journal of Sports Science 3 (2015) 195-202 doi: 10.17265/2332-7839/2015.04.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Wrestling: Glory of India at the Olympics—A Brief History of Indian Wresting Team in the Olympic Games Naveen Singh Suhag Department of Physical Education, Maharishi Dayanand University, Rohtak, Haryana 124001, India Abstract: Wrestling as an Olympic sport has been around since the dawn of modern Olympic games and India is a participating nation in it. Wrestling has unique position among Olympic disciplines in India, from being provider of first individual medal to newly independent nation to lately becoming most significant contributor in medal tally. This coming of age of Indian wrestling team with double medal tally in the last Olympics has been outcome of long and steady journey of Indian wrestling team over a period of 40-50 years and numerous Summer Olympic Games. However, this journey of Indian wrestling team in the Olympics is also a story of significant twist and turn, near misses and also of glory. So this article covers the entire saga of Indian wrestlers at highest sporting event of world—Olympic Games, from inception of first Indian team of mere three grapplers to latest Olympics with debut of first Indian female grappler in Olympic arena. This history is written by sweat and hard work of Indian grapplers with its own highs and lows. Key words: Indian wrestling team, the Olympics, wrestlers of India in Olympic Games, freestyle and Greco Roman Wrestling. 1. Introduction colonialism in third world countries. Wrestling along with shooting, as a discipline, share the second highest As a participating nation, India has a long history in number of medal haul in the Olympics for India. -

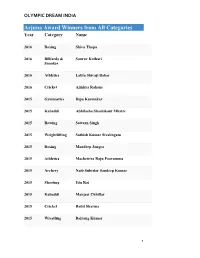

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

A Study on Flexibility and Agility in Yogic Exercise of the Kho-Kho And

Journal of Sports Science and Nutrition 2020; 1(1): 37-39 E-ISSN: 2707-7020 P-ISSN: 2707-7012 JSSN 2020; 1(1): 37-39 A study on flexibility and agility in yogic exercise of Received: 23-11-2019 Accepted: 25-12-2019 the kho-kho and kabaddi players Dr. Yallappa M M.P.Ed, K-SET, N.I.S, Ph.D, Dr. Yallappa M National kabaddi player, guest faculty, University college of physical Education, Bangalore Abstract university, Bangalore, The study was focused on yogic exercise have become very popular throughout the word due to its Karnataka, India utility. Physical education it’s have relealised its importance and have also tried to explore the effects towards physical fitness. Flexibility & Agility is one of important component of physical fitness. The present study was under taken on 40 Kabaddi and kho - kho Players, which are equally divided on the random basis as experimental group (N-20) and controlled group (N-20) using sit and reach test for flexibility and shuttle run test for measured agility both test was measured by before and after the training period of six weeks. During experimental period it was observed by the researcher that the subjects belonging to experimental group practiced yogic activities for six weeks. Subject was shown significant improvement in their flexibility, agility in comparison to the controlled group. Significant differences were noticed between pre and post test data of experimental and controlled group. Hence it is concluded yogic exercises for six weeks bring significant changes in flexibility, agility of kabaddi and kho-kho players. -

The Female Athlete and Spectacle in Bollywood: Reading Mary Kom and Dangal

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com GENERAL SECTION VOL: 9, No.: 2, AUTUMN 2019 REFREED, INDEXED, BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re- use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 68 | The Female Athlete and Spectacle in Bollywood… The Female Athlete and Spectacle in Bollywood: Reading Mary Kom and Dangal Shweta Sharma Abstract: This paper engages with the representation of the female athlete in Indian cinema. Specific references will be made to the cinematic portrayal of female boxers and wrestlers in Bollywood to argue that female boxers and wrestlers are portrayed as ‘masculine’. However, the sportswoman’s assertion of her femininity in a space exclusively occupied by men leads to ‘gender trouble’. To enunciate this argument two biopics, Mary Kom (2014) and Dangal (2016), will be analyzed. It would be observed that when a female boxer/wrestler tries to reinforce her identity, she is either subjected to criticism or faces failure. However, the argument that sportswomen are termed as ‘masculine’ does not necessarily imply that female athletes aren’t objects of the male gaze. -

93. Sudarsana Vaibhavam

. ïI>. Sri sudarshana vaibhavam sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Annotated Commentary in English By: Oppiliappan Koil SrI VaradAchAri SaThakopan 1&&& Sri Anil T (Hyderabad) . ïI>. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHAA STHOTHRAM sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org ANNOTATED COMMENTARY IN ENGLISH BY: OPPILIAPPAN KOIL SRI VARADACHARI SATHAGOPAN 2 CONTENTS Sri Shodhasayudha StOthram Introduction 5 SlOkam 1 8 SlOkam 2 9 SlOkam 3 10 SlOkam 4 11 SlOkam 5 12 SlOkam 6 13 SlOkam 7 14 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 8 15 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 9 16 SlOkam 10 17 SlOkam 11 18 SlOkam 12 19 SlOkam 13 20 SlOkam 14 21 SlOkam 15 23 SlOkam 16 24 3 SlOkam 17 25 SlOkam 18 26 SlOkam 19 (Phala Sruti) 27 Nigamanam 28 Sri Sudarshana Kavacham 29 - 35 Sri Sudarshana Vaibhavam 36 - 42 ( By Muralidhar Rangaswamy ) Sri Sudarshana Homam 43 - 46 Sri Sudarshana Sathakam Introduction 47 - 49 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Thiruvaymozhi 7.4 50 - 56 SlOkam 1 58 SlOkam 2 60 SlOkam 3 61 SlOkam 4 63 SlOkam 5 65 SlOkam 6 66 SlOkam 7 68 4 . ïI>. ïImteingmaNt mhadeizkay nm> . ;aefzayuxStaeÇt!. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHA STHOTHRAM Introduction sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Shodasa Ayutha means sixteen weapons of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar. This sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Sthothram is in praise of the glory of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar who is wielding sixteen weapons all of which are having a part of the power of the Chak- rAudham bestowed upon them. This Sthothram consists of 19 slOkams. The first slOkam is an introduction and refers to the 16 weapons adorned by Sri Sudarsana BhagavAn. -

Asian Games 2018 Question Answer

1. Who is the first Indian to win an Asian gold in the women's heptathlon event? a) Soma Biswas b) Dutee Chand c) Swapna Barman Techofworld.In d) Hima Das 2. Who has become the first Indian woman to win a gold medal in shooting at the Asian Games? a) Manu Baker b) Rahi Sarnobat c) Anjum Moudgil d) Heena Sidhu 3. Who became the first Indian woman wrestler to win a gold medal at the Asian Games? a) Geeta Phogat b) Vinesh Phogat c) Sakshi Malik d) Pooja Dhanda 4. Which Indian became the first badminton player to win silver in Asian Games? a) PV Sindhu b) Saina Nehwal c) Srikanth Kidambi d) HS Prannoy 5. Who has become the first Indian javelin thrower to win an Asian gold? a) Muhammed Anas b) Tajinder Pal Singh c) Dutee Chand d) Neeraj Chopra 6. Fouaad Mirza became the first Indian to win an Asian Games individual medal since 1982 in which sporting event? a) Wushu b) Equestrian c) Sepaktakraw Techofworld.In d) Bridge 7. Who won India’s first silver medal in Kurash at the 18th Asian Games in Indonesia? a) Pinky Balhara b) Malaprabha Yallapa Jadav c) Neena Varakil d) Sudha Singh 8. Who became the only second singles player to win an Asiad bronze in badminton at the 18th Asian Games? a) PV Sindhu b) Srikanth Kidambi c) Saina Nehwal d) Rohan Bopanna 9. Which two Indian players won gold in the tennis men’s doubles finals at Asian Games 2018? a) Rohan Bopanna and Yuki Bhambri b) Ramkumar Ramanathan and Divij Sharan c) Divij Sharan and Rohan Bopanna d) Somdev Devvarman and Ramkumar Ramanathan 10. -

Pak Violates Ceasefire Along Loc, IB in Rajouri, Samba

K K M M Y Y CHALLENGED DIFFERENTLY BLAME FOR AN ELECTION CHAMPIONS TROPHY C C Disabled children to be Pakistan, Sri Lanka British PM Theresa May’s top aides ambassadors of govt square off for Champions resign after election fiasco programme in Kerala nation, 7P Trophy semifinals spot sports, 9P world, 8P DAILY Price `2.00 Pages : 12 JAMMU MONDAYGlimpses | JUNE 12 2017 | VOL. 32 | NO. 161 | REGD. NO. : JM/JK 118/15 /17 | E-mail : [email protected] | epaper.glimpsesoffuture.comof Futurewww.glimpsesoffuture.com News Digest 5 militants killed in Uri CM discusses Pak violates ceasefire along were 'fidayeen': Army forthcoming legislature Srinagar, Jun 11 (PTI) session with Guv The Army today said the five militants killed in a counter-infiltration operation along the Line Srinagar, Jun 11 (PTI) LoC, IB in Rajouri, Samba of Control (LoC) in the Uri sector on Friday be- Jammu and Kashmir Chief longed to a 'fidayeen' squad and were planning a Minister Mehbooba Mufti today suicide attack. "So far, in the search operations, called on Governor N N Vohra and matics and mortars from 1240 in Bhimbher Gali sector in huge quantity of arms and ammunitions have hours along the Line of Rajouri," a senior army offi- been recovered, which includes five AK 47 rifles, See CM Discusses on page 11 Control in Naushera sector in cer said. The Indian Army two UBGLs, large quantity of explosives, combat Rajouri district, a defence posts are retaliating strongly dresses, incendiary material, eatables with Militants open fire on spokesman said. "The Indian and effectively. The firing is Pakistani markings and uniquely body-fitted Army posts are retaliating presently on, he said. -

ORDER Sr. Sh. Ashok Kumar S/O Sh. Umed Singh Fatehabad Sh. Balbir

ORDER In pursuance to Haryana Government Notification No. 1/83/2008-PR(FD) Dated 4.3.2014 read with Haryana Government Gazette Notification No. GSR. 45/Const/Art.309/08, dated 30.12.2008 and as provision made in Rule 7 and 8 of Haryana Civil Services (Assured Career Progression) Rule, 2008 following VLDA's are hereby granted 2" d Assured Career Progression in the scale of Rs. 9300-34800+Grade Pay 4000 w.e.f from the date mentioned against each after completion of regular satisfactory service of 16 years. Sr. Name/Parentage Date from which No. 2 nd ACP granted 1. Sh. Ashok Kumar S/o Sh. Umed Singh Fatehabad 4.3_2014 Sh. Balbir Singh S/o Sh. Mahabir Parsad (Hisar) 4.3.2014 3. Sh. Rishi Parkash S/o Sh. Attar Singh (Sonepat) 4.3.2014 4. Sh. Rajesh Kumar S/o Sh. Om Parkash (Jind) 4.3.2014 5. Sh. Vijay Kumar S/o Sh. Mange Ram (Rewari) 4.3.2014 6. Sh. Wazir Singh, S/o Sh. Chandgi Ram (Sonepat) 4.3.2014 7. Sh. Balwan Singh S/o Sh. Manphool Singh (Jind) 4.3 2014 8. Sh. lshwar Singh S/o Sh. Ram Bhul (Karnal) 4.3.2014 Sh. Ravinder Kumar S/o Sh. Ram Diya (Sonepat) 4.3.2014 10. Sh. Ram Phal Sic) Sh. Parbhu Ram (Fathehabad) 4.3.2014 11_ Sh. Rishi Parkash S/o Sh. Dhram Dutt (Sonepat) 4.3.2014 12. Sh. Sombir Singh S/o Sh. Bhale Ram (Rohtak) 4.3.2014 13_ Sh. Mahabir Singh S/o Sh. -

Unit 7 Customs, Rituals and Cults

UNIT 7 CUSTOMS, RITUALS AND CULTS ,. Structure 7.0 Objectives 7.1 Introduction 7.2 Customs and Rituals 7.2.1 Role and Functions of Rituals, Customs and Cerempnies 7.2.2 Types of Rituals and Customs 7.2.3 Customs and Rituals Related to Life Cycle 7.2.4 * Other Customs and Rituals 7.3 Cults 7.4 Sects 7A:l Hindu Sects 7.4.2 Muslim Sects 7.4.3 Sikh Sects 7.4.4 Budhist Sects 7.4.5 Jain Sects 7.4.6 Christian Sects 7.5 Let Us Sum UP 7.6 Answers to ~hkckYour Progress Exercises A Traditions1 Pqja st Tdacauvery, Kerala In this Unit we will discuss some important aspects of Indian society: Customs, rituals, cults and sects in India. After going through this unit you would know about: * ., significance of rituals and customs in Indian society the main rituals and customs followed among the various religious groups and communities in India important cults and sects in!ndia 7.1 . INTRODUCTION ) In Units 5 and 6 of this Block on society we discussed the structure of Indian society. Continying our discussion in this Unit we will discuss some other features of Indian society. Here we have included social and religious customs, rituals, cults and sects. To begin with we will try to define customs and rituals. Following this we will throw some light on the nature of rituals and customs. Next we will familiarize you with some rituals and customs practiced in diverse religious groups and communities in India. - From'earliest times there have emerged a number of cults and sects in India. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR ST MONDAY, THE 21 AUGUST, 2017 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 57 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 58 TO 61 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 62 TO 73 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 74 TO 85 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 21.08.2017 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 21.08.2017 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE C. HARI SHANKAR FOR ADMISSION _______________ 1. FAO(OS) 192/2017 NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY KV KINI LAW FIRM OF INDIA Vs. HINDUSTAN CONSTRUCTION CO. LTD. 2. FAO(OS) 195/2017 NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY MV KINI LAW FIRM,MALVIKA LAL OF INDIA Vs. HINDUSTAN CONSTRUCTION CO. LTD. 3. CM APPL. 17310/2017 BHAGWATI PRASAD S.P. SHARMA,ABHIMANYU CM APPL. 17311/2017 Vs. UNION OF INDIA & ORS BHANDARI,B.S.SHUKLA,S P In W.P.(C) 11076/2016 SHARMA (Disposed-off Case) 4. W.P.(C) 4141/2017 APPROVED GUIDE ASSOCIATION, PAWANSHREE AGRAWAL & AKARSH CM APPL. 18148/2017 AGRA & ORS GARG CM APPL. 18149/2017 Vs. UNION OF INDIA & ORS CM APPL. 18150/2017 CM APPL. 20997/2017 AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 5. FAO(OS) 45/2017 SUNIL PILLAY RAJAT BALI,RAJIV BAKSHI,JATIN CM APPL. 6745/2017 Vs. VIKRAM VEER BHATNAGAR & DHAWAN AND DEVENDRA ORS 6. CM APPL. 13003/2017 MEENAKSHI GAUTHAM AND ANR PRASHANT BHUSHAN,NEERAJ In W.P.(C) 13208/2009 Vs. -

(Aamir Khan) Adalah Mantan Atlet Gulat Yang Mengingink

BAB IV DESKRIPSI OBJEK PENELITIAN 4.1. Sinopsis Film Mahavir Singh Phogat (Aamir Khan) adalah mantan atlet gulat yang menginginkan anak laki-laki untuk dapat mewujudkan impiannya menjadikan anaknya sebagai pegulat agar memperoleh medali emas untuk Negara India, tetapi istrinya Daya Shobha Kaur (Sakshi Tanwar) melahirkan empat anak perempuan, sejak itu Mahavir Singh Phogat mengubur impiannya memiliki anak laki-laki. Keajaiban muncul ketika Geeta Kumari Phogat (anak pertama) dan Babita Kumari Phogat (anak kedua) memukul anak laki-laki tetangganya hingga luka parah, hal ini membuat Mahavir Singh Phogat kembali menjadikan kedua anaknya sebagai pegulat walaupun perempuan. 76 Mahavir Singh mulai melatihan gulat secara rutin kedua anak perempuannya, Geeta Kumari Phogat dan Babita Kumari Phogat, harus bangun jam 5 pagi latihan kemudian kembali dari sekolah lanjut latihan hingga malam bahkan Ayahnya berpesan pada istrinya untuk tidak melibatkan kedua putrinya dalam membantu pekerjaan rumah karena hanya akan fokus pada latihan gulat.77 Suatu ketikan kedua anak perempuan itu merasa jenuh dengan latihan terus-menerus dan dirampas dunia masa anak-anaknya untuk bermain bersama 76https://sinopsisfilmbioskopterbaru.com/dangal-2016-sinopsis-lengkap-film-dan/ diakses pada 26 Desember 2017 pkl 18.50 WIB. 77https://sinopsisfilmbioskopterbaru.com/dangal-2016-sinopsis-lengkap-film-dan/ diakses pada 26 Desember 2017 pkl 18.50 WIB. 46 teman-teman perempuannya bahkan rambut panjangnya dipotong agar tidak mengganggu dalam latihan gulat, dengan itu mereka mencari -

Asian Traditions of Wellness

BACKGROUND PAPER Asian Traditions of Wellness Gerard Bodeker DISCLAIMER This background paper was prepared for the report Asian Development Outlook 2020 Update: Wellness in Worrying Times. It is made available here to communicate the results of the underlying research work with the least possible delay. The manuscript of this paper therefore has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formally-edited texts. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. The ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this document and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or use of the term “country” in this document, is not intended to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this document do not imply any judgment on the part of the ADB concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. ASIAN TRADITIONS OF WELLNESS Gerard Bodeker, PhD Contents I. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................