Public and Inuit Interests, Baffin Island Caribou and Wildlife Management: Results of a Public Opinion Poll in Baffin Island Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

Victoria's Arctic Fashion Life in Antarctica Racing to Kimmirut

ISSUE 04 Racing to Kimmirut How to Stay Safe and Have Fun on Off-Road Vehicles Life in Antarctica COMIC PREPARING SKINS Victoria’s Arctic Nunavut Fashion Prospectors Takuttalirilli! Editors and Dorothy Milne Jordan Hoffman consultants Pascale Baillargeon Reena Qulitalik Dana Hopkins Caleb MacDonald Emma Renda Designer Larissa MacDonald Rachel Michael Jessie Hale Yulia Mychkina Maren Vsetula Denise Petipas Heather Main Julien Lagarde Nadia Mike Contributors Amanda Sandland Emma Renda Nancy Goupil Ibi Kaslik Dana Hopkins Laura Edlund Alexander Hoffman Department of Education, Government of Nunavut PO Box 1000, Station 960, Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 Design and layout copyright © 2018 Inhabit Education Text copyright © Inhabit Education Images: © Inhabit Media, front cover • © Kingulliit Productions, pages 2–3 • © Alexander Hoffman, pages 4–7 • © Chipmunk131/shutterstock.com, page 8 • © Alfa Photostudio/shutterstock.com, page 9 • © JAYANNPO/shutterstock.com, page 10 • © imageBROKER/alamy.com, page10 • © Rawpixel.com/shutterstock.com, page 11 • © Peyker/shutterstock.com, page 12 • © Department of Family and Services, Government of Nunavut, page 12 • © Everett Historical/shutterstock.com, page 13 • © Mike Beauregard/wikimedia.org, page 14 • © NASA, page 15 • © Sebastian Voortman/pexels.com, page 16 • © Davidee Qaumariaq, page 16 • © CHIARI VFX/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © nobeastsofierce/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Kateryna Kon/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Iasha/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Triff/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Vitaly Korovin/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Dcrjsr/wikimedia.org, page 20 • © Madlen/shutterstock.com, page 20 • © Olga Strakhova/shutterstock.com, page 20 • © Department of Health, Government of Nunavut, page 21 • © Amanda Sandland, pages 22–25 • © Suzanne Tucker/shutterstock.com, page 26 • © Jenson_P/wikimedia.org, page 28 • © Nowik Sylwia/shutterstock.com, page 29 • © Sherilyn Sewoee, page 31 • © Victoria Kakuktinniq, pages 32–33 • © Toma Feizo Gas, pages 34–40. -

Press Release Neas Awarded New Exclusive Carrier Contracts for Nunavut

PRESS RELEASE NEAS AWARDED NEW EXCLUSIVE CARRIER CONTRACTS FOR NUNAVUT - New for 2019: NEAS is now the Government of Nunavut’s (GN) dedicated carrier for Iqaluit, Cape Dorset, Kimmirut, Pangnirtung, Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Clyde River, Grise Fiord, Pond Inlet, Resolute Bay, Baker Lake, Chesterfield Inlet, Rankin Inlet, Whale Cove, Arviat, Coral Harbour, Kugaaruk, Sanikiluaq, and the Churchill, MB, to Kivalliq service. - Another arctic sealift first for 2019: Kugaaruk customers can now reserve direct with NEAS for the Valleyfield to Kugaaruk service, with no need to reserve through the GN; - “The team at NEAS is thankful for the Government of Nunavut’s vote of confidence in our reliable arctic sealift operations,” said Suzanne Paquin, President and CEO, NEAS Group. “We look forward to delivering our customer service excellence and a better overall customer sealift experience for all peoples, communities, government departments and agencies, stores, construction projects, mines, defence contractors and businesses across Canada’s Eastern and Western Arctic.” IQALUIT, NU, April 25, 2019 – The 2019 Arctic sealift season is underway, and the team of dedicated professionals at the NEAS Group is ready to help you enjoy the most reliable sealift services available across Canada’s Eastern and Western Arctic. New this season, NEAS is pleased to have been awarded the exclusive carrier contracts for the Government of Nunavut including Iqaluit and now Cape Dorset, Kimmirut, Pangnirtung, Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Clyde River, Grise Fiord, Pond Inlet, Resolute Bay, Baker Lake, Chesterfield Inlet, Rankin Inlet, Whale Cove, Arviat, Coral Harbour, Kugaaruk, Sanikiluaq, and the Churchill, MB, to Kivalliq service. No matter where you are across the Canadian Arctic, the NEAS team of dedicated employees and our modern fleet of Inuit-owned Canadian flag vessels is ready to deliver a superior sealift experience for you. -

Torngat Mountains National Park

TORNGAT MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK Presentation to Special Senate Committee on the Arctic November 19, 20018 1 PURPOSE Overview of the Torngat Mountains National Park Key elements include: • Indigenous partners and key commitments; • Cooperative Management structure; • Base Camp and Research Station overview & accomplishments; and • Next steps. 2 GEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT 3 INDIGENOUS PARTNERS • Inuit from Northern Labrador represented by Nunatsiavut Government • Inuit from Nunavik (northern Quebec) represented by Makivik Corporation 4 Cooperative Management What is it? Cooperative management is a model that involves Indigenous peoples in the planning and management of national parks without limiting the authority of the Minister under the Canada National Parks Act. What is the objective? To respect the rights and knowledge systems of Indigenous peoples by incorporating Indigenous history and cultures into management practices. How is it done? The creation of an incorporated Cooperative Management Board establishes a structure and process for Parks Canada and Indigenous peoples to regularly and meaningfully engage with each other as partners. 5 TORNGAT MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK CO-OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT BOARD 6 BASECAMP 7 EVOLUTION OF BASE CAMP 8 VALUE OF A BASE CAMP 9 10 ACCOMPLISHMENTS An emerging destination Tourism was a foreign concept before the park. It is now a destination in its own right. Cruise ships and sailing vessels are also finding their way here. Reconciliation in action Parks Canada has been working with Inuit to develop visitor experiences that will connect people to the park as an Inuit homeland. All of these experiences involve the participation of Inuit and help tell the story to the rest of the world in a culturally appropriate way. -

Recent Climate-Related Terrestrial Biodiversity Research in Canada's Arctic National Parks: Review, Summary, and Management Implications D.S

This article was downloaded by: [University of Canberra] On: 31 January 2013, At: 17:43 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biodiversity Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tbid20 Recent climate-related terrestrial biodiversity research in Canada's Arctic national parks: review, summary, and management implications D.S. McLennan a , T. Bell b , D. Berteaux c , W. Chen d , L. Copland e , R. Fraser d , D. Gallant c , G. Gauthier f , D. Hik g , C.J. Krebs h , I.H. Myers-Smith i , I. Olthof d , D. Reid j , W. Sladen k , C. Tarnocai l , W.F. Vincent f & Y. Zhang d a Parks Canada Agency, 25 Eddy Street, Hull, QC, K1A 0M5, Canada b Department of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NF, A1C 5S7, Canada c Chaire de recherche du Canada en conservation des écosystèmes nordiques and Centre d’études nordiques, Université du Québec à Rimouski, 300 Allée des Ursulines, Rimouski, QC, G5L 3A1, Canada d Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, Natural Resources Canada, 588 Booth St., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0Y7, Canada e Department of Geography, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada f Département de biologie and Centre d’études nordiques, Université Laval, G1V 0A6, Quebec, QC, Canada g Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E9, Canada h Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada i Département de biologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, J1K 2R1, Canada j Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, Whitehorse, YT, Y1A 5T2, Canada k Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth St., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0E8, Canada l Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0C6, Canada Version of record first published: 07 Nov 2012. -

TAB 3C GN DOE 2019 BIC HTO Consultation Summary Report

Consultations with Hunting and Trapping Organizations on the Baffin Island Caribou Composition Survey Results, Future Research Recommendations, and Draft Management Plan January 7-18, 2019 Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Iqaluit, Nunavut Executive Summary Government of Nunavut (GN), Department of Environment (DOE) representatives conducted consultations with Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTOs) in the Baffin region from January 7-18, 2019. The intent of this round of consultations was to ensure HTOs were informed on the results of caribou abundance and composition surveys from 2014 to present on Baffin Island. DOE presented options for future research on Baffin Island including a telemetry-based collaring program. The feedback collected during this round of consultations will aid the GN in future research planning and monitoring for Baffin Island caribou. This report attempts to summarize the comments made by participants during the round of consultations. Baffin Island Caribou Consultation Summary Report Page i of 45 Preface This report represents the Department of Environment’s best efforts to accurately capture all of the information that was shared during consultation meetings with the Hunters and Trappers Organizations of Kimmirut, Qikiqtarjuaq, Pangnirtung, Iqaluit, Cape Dorset, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Arctic Bay and Pond Inlet. Unfortunately during this consultation tour weather prevented us from meeting with Clyde River but the DOE is currently planning to meet with the HTO in February 2019. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Environment, or the Government of Nunavut. Baffin Island Caribou Consultation Summary Report Page ii of 45 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... i Preface ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Download (7MB)

The Glaciers of the Torngat Mountains of Northern Labrador By © Robert Way A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Geography Memorial University of Newfoundland September 2013 St. John 's Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract The glaciers of the Tomgat Mountains of northem Labrador are the southemmost m the eastern Canadian Arctic and the most eastem glaciers in continental North America. This thesis presents the first complete inventory of the glaciers of the Tomgat Mountains and also the first comprehensive change assessment for Tomgat glaciers over any time period. In total, 195 ice masses are mapped with 105 of these showing clear signs of active glacier flow. Analysis of glaciers and ice masses reveal strong influences of local topographic setting on their preservation at low elevations; often well below the regional glaciation level. Coastal proximity and latitude are found to exert the strongest control on the distribution of glaciers in the Tomgat Mountains. Historical glacier changes are investigated using paleomargins demarking fanner ice positions during the Little Ice Age. Glacier area for 165 Torngat glaciers at the Little Ice Age is mapped using prominent moraines identified in the forelands of most glaciers. Overall glacier change of 53% since the Little Ice Age is dete1mined by comparing fanner ice margins to 2005 ice margins across the entire Torngat Mountains. Field verification and dating of Little Ice Age ice positions uses lichenometry with Rhizocarpon section lichens as the target subgenus. The relative timing of Little Ice Age maximum extent is calculated using lichens measured on moraine surfaces in combination with a locally established lichen growth curve from direct measurements of lichen growth over a - 30 year period. -

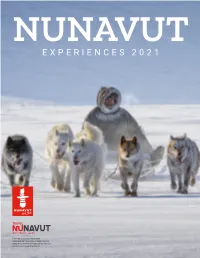

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

Kimmirut 2013

Kimmirut 2013 The community of Kimmirut, previously known as Lake Harbour, is a picturesque town located on the southern coast of Baffin Island, near the mouth of the Soper River. Hikers access the Katannilik Territorial Park Reserve from just outside the community. Other outdoor pursuits enjoyed in the area are sea kayaking, canoeing, and hunting. Kimmirut has a lot to offer its visitors; residents are continuing to promote their community’s tourism industry from both within and outside the territory. Such efforts have resulted in cruise ship stops, guide and outfitting services and a community website. Many of Kimmirut’s residents are renowned carvers whose art is sold and collected worldwide. For more information about Kimmirut and its surrounding attractions, visit the Kimmirut website at: www.kimmirut.ca . Getting There: First Air operates flights from Iqaluit to Kimmirut on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. Kenn Borek Air also flies to Kimmirut from Iqaluit on Monday and Friday. Please check with the airlines for schedule changes. Community Services and Information Population 460 Region Qikiqtani Time Zone Eastern Postal Code X0A 0N0 Population based on 2012 Nunavut Bureau of Statistics (Area Code is 867 unless as indicated) RCMP General Inquiries 939-0123 Local Communications Emergency Only 939-1111 Internet 979-0772 Health Centre 939-2217 Community website: www.kimmirut.ca Fire Emergency 939-4422 Cable 939-2322 Post Office 939-2002 Radio Society 939-2126 Schools/College Airport 939-2250 Qaqqalik (K-12) 939-2221 Arctic College 939-2414 Hunters and Trappers Organization 939-2355 Early Childhood Services The Katannilik Park Centre 939-2416 Kimmirut Pairivik Day Care 939-2122 Banks Churches Light banking services available at the Northern and Co-op St. -

Across Borders, for the Future: Torngat Mountains Caribou Herd Inuit

ACROSS BORDERS, FOR THE FUTURE: Torngat Mountains Caribou Herd Inuit Knowledge, Culture, and Values Study Prepared for the Nunatsiavut Government and Makivik Corporation, Parks Canada, and the Torngat Wildlife and Plants Co-Management Board - June 2014 This report may be cited as: Wilson KS, MW Basterfeld, C Furgal, T Sheldon, E Allen, the Communities of Nain and Kangiqsualujjuaq, and the Co-operative Management Board for the Torngat Mountains National Park. (2014). Torngat Mountains Caribou Herd Inuit Knowledge, Culture, and Values Study. Final Report to the Nunatsiavut Government, Makivik Corporation, Parks Canada, and the Torngat Wildlife and Plants Co-Management Board. Nain, NL. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of the authors. Inuit Knowledge is intellectual property. All Inuit Knowledge is protected by international intellectual property rights of Indigenous peoples. As such, participants of the Torngat Mountains Caribou Herd Inuit Knowledge, Culture, and Values Study reserve the right to use and make public parts of their Inuit Knowledge as they deem appropriate. Use of Inuit Knowledge by any party other than hunters and Elders of Nunavik and Nunatsiavut does not infer comprehensive understanding of the knowledge, nor does it infer implicit support for activities or projects in which this knowledge is used in print, visual, electronic, or other media. Cover photo provided by and used with permission from Rodd Laing. All other photos provided by the lead author. -

Visitor Guide Photo Pat Morrow

Visitor Guide Photo Pat Morrow Bear’s Gut Contact Us Nain Office Nunavik Office Telephone: 709-922-1290 (English) Telephone: 819-337-5491 Torngat Mountains National Park has 709-458-2417 (French) (English and Inuttitut) two offices: the main Administration Toll Free: 1-888-922-1290 Toll Free: 1-888-922-1290 (English) office is in Nain, Labrador (open all E-Mail: [email protected] 709-458-2417 (French) year), and a satellite office is located in Fax: 709-922-1294 E-Mail: [email protected] Kangiqsualujjuaq in Nunavik (open from Fax: 819-337-5408 May to the end of October). Business hours Mailing address: Mailing address: are Monday-Friday 8 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. Torngat Mountains National Park Torngat Mountains National Park, Box 471, Nain, NL Box 179 Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik, QC A0P 1L0 J0M 1N0 Street address: Street address: Illusuak Cultural Centre Building 567, Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik, QC 16 Ikajutauvik Road, Nain, NL In Case Of Emergency In case of an emergency in the park, Be prepared to tell the dispatcher: assistance will be provided through the • The name of the park following 24 hour emergency numbers at • Your name Jasper Dispatch: • Your sat phone number 1-877-852-3100 or 1-780-852-3100. • The nature of the incident • Your location - name and Lat/Long or UTM NOTE: The 1-877 number may not work • The current weather – wind, precipitation, with some satellite phones so use cloud cover, temperature, and visibility 1-780-852-3100. 1 Welcome to TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Torngat Mountains National Park 1 Welcome 2 An Inuit Homeland The spectacular landscape of Torngat Mountains Planning Your Trip 4 Your Gateway to Torngat National Park protects 9,700 km2 of the Northern Mountains National Park 5 Torngat Mountains Base Labrador Mountains natural region. -

North-East Passage

WORLD OF BIRDS Reproduced from the May 2018 issue (311: 45-48) North-east passage A voyage through Canada’s icy waters from Nova Scotia to Frobisher Bay delivered seabirds galore and a host of marine mammals, among many other wildlife highlights. Rod Standing reports on the experience of a lifetime. olar Bear, 3 o’clock, 1 We started our journey some kilometre!” I train the 1,200 miles to the south, in “Pscope across the pressure Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, ridges of the ice pack and the huge by getting better acquainted butter-yellow bear stands out clearly with some North American against the sparkling white snow. It species previously known to me only as lifts its head to sni the chill air and vagrants. At the historic fortress on a then continues its quest for seals. A grassy promontory south of the town, Brünnich’s Guillemot stands like a American Cli Swallows hawk around miniature penguin on a nearby fl oe the buildings, the adults brightly and an immaculate adult Iceland coloured red, brown and cream, in Gull slides past. contrast with the drab juvenile I saw in We are on the deck of the Akademik Su olk in 2016. A Greater Yellowlegs, Sergei Vavalov, a polar research alerting me with its tew-tew-tew call – ship chartered by One Ocean very similar to Greenshank – circles a Expeditions, under brilliant blue small pool looking for a landing place. skies in Frobisher Bay, a huge sea Family parties of Green-winged Teal inlet in Ba n Island, north-east swim about like town park Mallards.