In Appreciation of Abner Shimony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bachelorarbeit

Bachelorarbeit The EPR-Paradox, Nonlocality and the Question of Causality Ilvy Schultschik angestrebter akademischer Grad Bachelor of Science (BSc) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: 033 676 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Physik Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Reinhold A. Bertlmann Contents 1 Motivation and Mathematical framework 2 1.1 Entanglement - Separability . .2 1.2 Schmidt Decomposition . .3 2 The EPR-paradox 5 2.1 Introduction . .5 2.2 Preface . .5 2.3 EPR reasoning . .8 2.4 Bohr's reply . 11 3 Hidden Variables and no-go theorems 12 4 Nonlocality 14 4.1 Nonlocality and Quantum non-separability . 15 4.2 Teleportation . 17 5 The Bell theorem 19 5.1 Bell's Inequality . 19 5.2 Derivation . 19 5.3 Violation by quantum mechanics . 21 5.4 CHSH inequality . 22 5.5 Bell's theorem and further discussion . 24 5.6 Different assumptions . 26 6 Experimental realizations and loopholes 26 7 Causality 29 7.1 Causality in Special Relativity . 30 7.2 Causality and Quantum Mechanics . 33 7.3 Remarks and prospects . 34 8 Acknowledgment 35 1 1 Motivation and Mathematical framework In recent years, many physicists have taken the incompatibility between cer- tain notions of causality, reality, locality and the empirical data less and less as a philosophical discussion about interpretational ambiguities. Instead sci- entists started to regard this tension as a productive resource for new ideas about quantum entanglement, quantum computation, quantum cryptogra- phy and quantum information. This becomes especially apparent looking at the number of citations of the original EPR paper, which has risen enormously over recent years, and be- coming the starting point for many groundbreaking ideas. -

Many Worlds Model Resolving the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox Via a Direct Realism to Modal Realism Transition That Preserves Einstein Locality

Many Worlds Model resolving the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox via a Direct Realism to Modal Realism Transition that preserves Einstein Locality Sascha Vongehr †,†† †Department of Philosophy, Nanjing University †† National Laboratory of Solid-State Microstructures, Thin-film and Nano-metals Laboratory, Nanjing University Hankou Lu 22, Nanjing 210093, P. R. China The violation of Bell inequalities by quantum physical experiments disproves all relativistic micro causal, classically real models, short Local Realistic Models (LRM). Non-locality, the infamous “spooky interaction at a distance” (A. Einstein), is already sufficiently ‘unreal’ to motivate modifying the “realistic” in “local realistic”. This has led to many worlds and finally many minds interpretations. We introduce a simple many world model that resolves the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. The model starts out as a classical LRM, thus clarifying that the many worlds concept alone does not imply quantum physics. Some of the desired ‘non-locality’, e.g. anti-correlation at equal measurement angles, is already present, but Bell’s inequality can of course not be violated. A single and natural step turns this LRM into a quantum model predicting the correct probabilities. Intriguingly, the crucial step does obviously not modify locality but instead reality: What before could have still been a direct realism turns into modal realism. This supports the trend away from the focus on non-locality in quantum mechanics towards a mature structural realism that preserves micro causality. Keywords: Many Worlds Interpretation; Many Minds Interpretation; Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox; Everett Relativity; Modal Realism; Non-Locality PACS: 03.65. Ud 1 1 Introduction: Quantum Physics and Different Realisms ............................................................... -

Hidden Variables and the Two Theorems of John Bell

Hidden Variables and the Two Theorems of John Bell N. David Mermin What follows is the text of my article that appeared in Reviews of Modern Physics 65, 803-815 (1993). I’ve corrected the three small errors posted over the years at the Revs. Mod. Phys. website. I’ve removed two decorative figures and changed the other two figures into (unnumbered) displayed equations. I’ve made a small number of minor editorial improvements. I’ve added citations to some recent critical articles by Jeffrey Bub and Dennis Dieks. And I’ve added a few footnotes of commentary.∗ I’m posting my old paper at arXiv for several reasons. First, because it’s still timely and I’d like to make it available to a wider audience in its 25th anniversary year. Second, because, rereading it, I was struck that Section VII raises some questions that, as far as I know, have yet to be adequately answered. And third, because it has recently been criticized by Bub and Dieks as part of their broader criticism of John Bell’s and Grete Hermann’s reading of John von Neumann.∗∗ arXiv:1802.10119v1 [quant-ph] 27 Feb 2018 ∗ The added footnotes are denoted by single or double asterisks. The footnotes from the original article have the same numbering as in that article. ∗∗ R¨udiger Schack and I will soon post a paper in which we give our own view of von Neumann’s four assumptions about quantum mechanics, how he uses them to prove his famous no-hidden-variable theorem, and how he fails to point out that one of his assump- tions can be violated by a hidden-variables theory without necessarily doing violence to the whole structure of quantum mechanics. -

Lessons of Bell's Theorem

Lessons of Bell's Theorem: Nonlocality, yes; Action at a distance, not necessarily. Wayne C. Myrvold Department of Philosophy The University of Western Ontario Forthcoming in Shan Gao and Mary Bell, eds., Quantum Nonlocality and Reality { 50 Years of Bell's Theorem (Cambridge University Press) Contents 1 Introduction page 1 2 Does relativity preclude action at a distance? 2 3 Locally explicable correlations 5 4 Correlations that are not locally explicable 8 5 Bell and Local Causality 11 6 Quantum state evolution 13 7 Local beables for relativistic collapse theories 17 8 A comment on Everettian theories 19 9 Conclusion 20 10 Acknowledgments 20 11 Appendix 20 References 25 1 Introduction 1 1 Introduction Fifty years after the publication of Bell's theorem, there remains some con- troversy regarding what the theorem is telling us about quantum mechanics, and what the experimental violations of Bell inequalities are telling us about the world. This chapter represents my best attempt to be clear about what I think the lessons are. In brief: there is some sort of nonlocality inherent in any quantum theory, and, moreover, in any theory that reproduces, even approximately, the quantum probabilities for the outcomes of experiments. But not all forms of nonlocality are the same; there is a distinction to be made between action at a distance and other forms of nonlocality, and I will argue that the nonlocality needed to violate the Bell inequalities need not involve action at a distance. Furthermore, the distinction between forms of nonlocality makes a difference when it comes to compatibility with relativis- tic causal structure. -

PROPOSED EXPERIMENT to TEST LOCAL HIDDEN-VARIABLE THEORIES* John F

VOLUME 23, NUMBER 15 PHYSI CA I. REVIEW I.ETTERS 13 OcToBER 1969 sible without the devoted effort of the personnel ~K. P. Beuermann, C. J. Rice, K. C. Stone, and R. K. of the Orbiting Geophysical Observatory office Vogt, Phys. Rev. Letters 22, 412 (1969). at the Goddard Space Flight Center and at TR%. 2J. L'Heureux and P. Meyer, Can. J. Phys. 46, S892 (1968). 3J. Rockstroh and W. R. Webber, University of Min- nesota Publication No. CR-126, 1969. ~Research supported in part under National Aeronau- 46. M. Simnett and F. B. McDonald, Goddard Space tics and Space Administration Contract No. NAS 5-9096 Plight Center Report No. X-611-68-450, 1968 (to be and Grant No. NGR 14-001-005. published) . )Present address: Department of Physics, The Uni- 5W. R. Webber, J. Geophys. Res. 73, 4905 (1968). versity of Arizona, Tucson, Ariz. GP. B. Abraham, K. A. Brunstein, and T. L. Cline, (Also Department of Physics. Phys. Rev. 150, 1088 (1966). PROPOSED EXPERIMENT TO TEST LOCAL HIDDEN-VARIABLE THEORIES* John F. Clauserf Department of Physics, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027 Michael A. Horne Department of Physics, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 and Abner Shimony Departments of Philosophy and Physics, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 and Richard A. Holt Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 (Received 4 August 1969) A theorem of Bell, proving that certain predictions of quantum mechanics are incon- sistent with the entire family of local hidden-variable theories, is generalized so as to apply to realizable experiments. A proposed extension of the experiment of Kocher and Commins, on the polarization correlation of a pair of optical photons, will provide a de- cisive test betw'een quantum mechanics and local hidden-variable theories. -

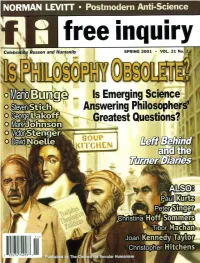

Is Emerging Science Answering Philosopher: Greatest Questions?

free inquiry SPRING 2001 • VOL. 21 No. Is Emerging Science Answering Philosopher: Greatest Questions? ALSO: Paul Kurtz Peter Christina Hoff Sommers Tibor Machan Joan Kennedy Taylor Christopher Hitchens `Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: LI I A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES free inquiry We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual under- standing. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual ori- entation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suf- fering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. -

Quantum Field Theory Motivated Model for the Einstein, Podolsky, Rosen (EPR) Experiment

Canadian Journal of Physics Quantum Field Theory Motivated Model for the Einstein, Podolsky, Rosen (EPR) Experiment Journal: Canadian Journal of Physics Manuscript ID cjp-2019-0537.R2 Manuscript Type:ForPoint Reviewof View Only Date Submitted by the 12-Mar-2020 Author: Complete List of Authors: Schatten, Kenneth; a.i. Solutions, Inc., Physics Research Jacobs, V.J.; Naval Research Laboratory Quantum Field Theory, Electron Dressing, EPR, Einstein, Podolsky and Keyword: Rosen Experiment, Probabilistic Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Not applicable (regular submission) Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 11 Canadian Journal of Physics Quantum Field Theory Motivated Model for the Einstein, Podolsky, Rosen (EPR) Experiment For ReviewKenneth H. Schatten* Only NASA/GSFC Greenbelt, MD 20771 *now at: ai-Solutions, Inc. Lanham, MD 20706 and Verne L. Jacobs Center for Computational Materials Science, Code 6390, Materials Science and Technology Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, D. C. 20375-5345 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Physics Page 2 of 11 Abstract Bell deduced the nature and form of “nonlocal hidden variables” that could yield the unusual pattern of responses in the paradoxical Bohm (B-EPR) version of the Einstein, Podolsky, Rosen (EPR) experiment. We consider that Quantum Field Theory (QFT)allows for the existence of Bell’s hidden variables in the “dressing” of free electrons that may explain the EPR experimental results. Specifically, the dressing of free electrons can convey random vector information. Motivated by this, we use a random vector paradigm (RVP) to explore how well a Monte Carlo computer program compares with the experimental B-EPR statistics. -

Nonlocal Polarization Interferometry and Entanglement Detection

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2014 Nonlocal Polarization Interferometry and Entanglement Detection Brian P. Williams University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics Commons, and the Quantum Physics Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Brian P., "Nonlocal Polarization Interferometry and Entanglement Detection. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Brian P. Williams entitled "Nonlocal Polarization Interferometry and Entanglement Detection." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Physics. Joseph Macek, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Warren Grice, Robert Compton, Norman Mannella, Ray Garrett Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Nonlocal Polarization Interferometry and Entanglement Detection A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Brian P. -

Making Sense of Bell's Theorem and Quantum Nonlocality

Making Sense of Bell's Theorem and Quantum Nonlocality∗ Stephen Boughny Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544 Haverford College, Haverford PA 19041 LATEX-ed April 3, 2017 Abstract Bell's theorem has fascinated physicists and philosophers since his 1964 paper, which was written in response to the 1935 paper of Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen. Bell's theorem and its many extensions have led to the claim that quantum mechan- ics and by inference nature herself are nonlocal in the sense that a measurement on a system by an observer at one location has an immediate effect on a distant entangled system (one with which the original system has previously interacted). Einstein was repulsed by such \spooky action at a distance" and was led to ques- tion whether quantum mechanics could provide a complete description of physical reality. In this paper I argue that quantum mechanics does not require spooky action at a distance of any kind and yet it is entirely reasonable to question the arXiv:1703.11003v1 [quant-ph] 31 Mar 2017 assumption that quantum mechanics can provide a complete description of physical reality. The magic of entangled quantum states has little to do with entanglement and everything to do with superposition, a property of all quantum systems and a foundational tenet of quantum mechanics. Keywords: Quantum nonlocality · Bell's theorem · Foundations of quantum me- chanics · Measurement problem ∗This is an expanded version of a talk given at the 2016 Princeton-TAMU Symposium on Quantum Noise Effects in Thermodynamics, Biology and Information [1]. [email protected] 1 2 1 Introduction In the 80 years since the seminal 1935 Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paper (EPR)[2], physi- cists and philosophers have mused about what Einstein referred to as \spooky action at a distance". -

Quantum State Diffusion: from Foundations to Applications

Quantum State Diffusion: from Foundations to Applications by Nicolas Gisin Group of Applied Physics University of Geneva and Ian C Percival Department of Physics Queen Mary and Westfield College, University of London Abstract Deeper insight leads to better practice. We show how the study of the foundations of quantum mechanics has led to new pictures of open systems and to a method of computation which is practical and can be used where others cannot. We illustrate the power of the new method by a series of pictures that show the emergence of classical features in a quantum world. We compare the development of quantum mechanics and of the theory of (biological) evolution. arXiv:quant-ph/9701024v1 20 Jan 1997 96January9th,QMWTH96- TocelebrateAbnerShimony 1 1. Introduction Stochastic modifications of the Schr¨odinger equation have been proven to be useful in a variety of contexts, ranging from fundamental new theories to practical compu- tations. In this contribution dedicated to Abner Shimony we recall the motivations which led us to work in this field and present some thoughts about what such modi- fications could mean for future theories. As we shall see, both of these topics are at the border between physics and philosophy, what Abner likes to call ”experimental methaphysics”. For Albert Einstein, John Bell and Abner Shimony a quantum theory which can be used to analyse experiments, but which does not present a consistent and com- plete representation of the world in which we live, is not enough. In recent years their ranks have been joined by many others, including those who have proposed alternative quantum theories to remedy this defect. -

Title Page: 21 December 2010

Journal of American Science, 2011;7(5) http://www.americanscience.org The Speed of light A Fundamental Retrospection to Prospection Narendra Katkar Author – Investigator – Analyst, Founder-Chair International Research Center for Fundamental Sciences (IRCFS) 4-158/41, Plot No.41, Sai Puri, Sainikpuri, Secunderabad, 500094: Andhra Pradesh, INDIA Webpage: https://sites.google.com/site/ircfsnk/home; Email: [email protected] Abstract: Speed of light can not be achieved independently by any Body even a Photon, unless it has a source, a thrust of that speed. Further, no amount of radiation or light form can be produced freely, unless some amount of (mass) rest energy is converted to dynamic liberated energy. With the investigation of above query and retrospection in mass- energy relation, a paradigm shift in understanding fundamental nature of Energy and Universe is presented. [Narendra Katkar. The Speed of light - A Fundamental Retrospection to Prospection. Journal of American Science 2011;7(5):113-127]. (ISSN: 1545-1003). http://www.americanscience.org. Key words: Light Speed, photon, electron positron interaction, Energy, Universe Introduction as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality." See note. Physics is a natural science and attempts to The scientific community has responsibility to present general analysis of nature; carried out with the communicate to citizens of the world and the purpose to understand how the universe works. governments, the exact nature of fundamental features (Feynman, Leighton, Sands (1963), -

Bell's Theorem and Its First Experimental Tests

ARTICLE IN PRESS Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 37 (2006) 577–616 www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsb Philosophy enters the optics laboratory: Bell’s theorem and its first experimental tests (1965–1982) Olival Freire Jr. Instituto de Fı´sica, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, BA 40210-340, Brazil Received 27 June 2005; received in revised form 22 November 2005; accepted 2 December 2005 Abstract This paper deals with the ways that the issue of completing quantum mechanics was brought into laboratories and became a topic in mainstream quantum optics. It focuses on the period between 1965, when Bell published what we now call Bell’s theorem, and 1982, when Aspect published the results of his experiments. Discussing some of those past contexts and practices, I show that factors in addition to theoretical innovations, experiments, and techniques were necessary for the flourishing of this subject, and that the experimental implications of Bell’s theorem were neither suddenly recognized nor quickly highly regarded by physicists. Indeed, I will argue that what was considered good physics after Aspect’s 1982 experiments was once considered by many a philosophical matter instead of a scientific one, and that the path from philosophy to physics required a change in the physics community’s attitude about the status of the foundations of quantum mechanics. r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: History of physics; Quantum physics; Bell’s theorem; Entanglement; Hidden-variables; Scientific controversies 1. Introduction Quantum non-locality, or entanglement, that is the quantum correlations between systems (photons, electrons, etc.) that are spatially separated, is the key physical effect in the burgeoning and highly funded search for quantum cryptography and computation.