Bell's Theorem and Its First Experimental Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Noise in Quantum Optics: the Stochastic Schr\" Odinger

Quantum Noise in Quantum Optics: the Stochastic Schr¨odinger Equation Peter Zoller † and C. W. Gardiner ∗ † Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria ∗ Department of Physics, Victoria University Wellington, New Zealand February 1, 2008 arXiv:quant-ph/9702030v1 12 Feb 1997 Abstract Lecture Notes for the Les Houches Summer School LXIII on Quantum Fluc- tuations in July 1995: “Quantum Noise in Quantum Optics: the Stochastic Schroedinger Equation” to appear in Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. 1997, edited by E. Giacobino and S. Reynaud. 0.1 Introduction Theoretical quantum optics studies “open systems,” i.e. systems coupled to an “environment” [1, 2, 3, 4]. In quantum optics this environment corresponds to the infinitely many modes of the electromagnetic field. The starting point of a description of quantum noise is a modeling in terms of quantum Markov processes [1]. From a physical point of view, a quantum Markovian description is an approximation where the environment is modeled as a heatbath with a short correlation time and weakly coupled to the system. In the system dynamics the coupling to a bath will introduce damping and fluctuations. The radiative modes of the heatbath also serve as input channels through which the system is driven, and as output channels which allow the continuous observation of the radiated fields. Examples of quantum optical systems are resonance fluorescence, where a radiatively damped atom is driven by laser light (input) and the properties of the emitted fluorescence light (output)are measured, and an optical cavity mode coupled to the outside radiation modes by a partially transmitting mirror. -

Quantum Computation and Complexity Theory

Quantum computation and complexity theory Course given at the Institut fÈurInformationssysteme, Abteilung fÈurDatenbanken und Expertensysteme, University of Technology Vienna, Wintersemester 1994/95 K. Svozil Institut fÈur Theoretische Physik University of Technology Vienna Wiedner Hauptstraûe 8-10/136 A-1040 Vienna, Austria e-mail: [email protected] December 5, 1994 qct.tex Abstract The Hilbert space formalism of quantum mechanics is reviewed with emphasis on applicationsto quantum computing. Standardinterferomeric techniques are used to construct a physical device capable of universal quantum computation. Some consequences for recursion theory and complexity theory are discussed. hep-th/9412047 06 Dec 94 1 Contents 1 The Quantum of action 3 2 Quantum mechanics for the computer scientist 7 2.1 Hilbert space quantum mechanics ..................... 7 2.2 From single to multiple quanta Ð ªsecondº ®eld quantization ...... 15 2.3 Quantum interference ............................ 17 2.4 Hilbert lattices and quantum logic ..................... 22 2.5 Partial algebras ............................... 24 3 Quantum information theory 25 3.1 Information is physical ........................... 25 3.2 Copying and cloning of qbits ........................ 25 3.3 Context dependence of qbits ........................ 26 3.4 Classical versus quantum tautologies .................... 27 4 Elements of quantum computatability and complexity theory 28 4.1 Universal quantum computers ....................... 30 4.2 Universal quantum networks ........................ 31 4.3 Quantum recursion theory ......................... 35 4.4 Factoring .................................. 36 4.5 Travelling salesman ............................. 36 4.6 Will the strong Church-Turing thesis survive? ............... 37 Appendix 39 A Hilbert space 39 B Fundamental constants of physics and their relations 42 B.1 Fundamental constants of physics ..................... 42 B.2 Conversion tables .............................. 43 B.3 Electromagnetic radiation and other wave phenomena ......... -

An Original Way of Teaching Geometrical Optics C. Even

Learning through experimenting: an original way of teaching geometrical optics C. Even1, C. Balland2 and V. Guillet3 1 Laboratoire de Physique des Solides, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, F-91405 Orsay, France 2 Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Université Paris 6, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cite, CNRS-IN2P3, Laboratoire de Physique Nucléaire et des Hautes Energies (LPNHE), 4 place Jussieu, F-75252, Paris Cedex 5, France 3 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, F- 91405 Orsay, France E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Over the past 10 years, we have developed at University Paris-Sud a first year course on geometrical optics centered on experimentation. In contrast with the traditional top-down learning structure usually applied at university, in which practical sessions are often a mere verification of the laws taught during preceding lectures, this course promotes “active learning” and focuses on experiments made by the students. Interaction among students and self questioning is strongly encouraged and practicing comes first, before any theoretical knowledge. Through a series of concrete examples, the present paper describes the philosophy underlying the teaching in this course. We demonstrate that not only geometrical optics can be taught through experiments, but also that it can serve as a useful introduction to experimental physics. Feedback over the last ten years shows that our approach succeeds in helping students to learn better and acquire motivation and autonomy. This approach can easily be applied to other fields of physics. Keywords : geometrical optics, experimental physics, active learning 1. Introduction Teaching geometrical optics to first year university students is somewhat challenging, as this field of physics often appears as one of the less appealing to students. -

Quantum Memories for Continuous Variable States of Light in Atomic Ensembles

Quantum Memories for Continuous Variable States of Light in Atomic Ensembles Gabriel H´etet A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The Australian National University October, 2008 ii Declaration This thesis is an account of research undertaken between March 2005 and June 2008 at the Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Australian National University (ANU), Can- berra, Australia. This research was supervised by Prof. Ping Koy Lam (ANU), Prof. Hans- Albert Bachor (ANU), Dr. Ben Buchler (ANU) and Dr. Joseph Hope (ANU). Unless otherwise indicated, the work present herein is my own. None of the work presented here has ever been submitted for any degree at this or any other institution of learning. Gabriel H´etet October 2008 iii iv Acknowledgments I would naturally like to start by thanking my principal supervisors. Ping Koy Lam is the person I owe the most. I really appreciated his approachability, tolerance, intuition, knowledge, enthusiasm and many other qualities that made these three years at the ANU a great time. Hans Bachor, for helping making this PhD in Canberra possible and giving me the opportunity to work in this dynamic research environment. I always enjoyed his friendliness and general views and interpretations of physics. Thanks also to both of you for the opportunity you gave me to travel and present my work to international conferences. This thesis has been a rich experience thanks to my other two supervisors : Joseph Hope and Ben Buchler. I would like to thank Joe for invaluable help on the theory and computer side and Ben for the efficient moments he spent improving the set-up and other innumerable tips that polished up the work presented here, including proof reading this thesis. -

Bachelorarbeit

Bachelorarbeit The EPR-Paradox, Nonlocality and the Question of Causality Ilvy Schultschik angestrebter akademischer Grad Bachelor of Science (BSc) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: 033 676 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Physik Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Reinhold A. Bertlmann Contents 1 Motivation and Mathematical framework 2 1.1 Entanglement - Separability . .2 1.2 Schmidt Decomposition . .3 2 The EPR-paradox 5 2.1 Introduction . .5 2.2 Preface . .5 2.3 EPR reasoning . .8 2.4 Bohr's reply . 11 3 Hidden Variables and no-go theorems 12 4 Nonlocality 14 4.1 Nonlocality and Quantum non-separability . 15 4.2 Teleportation . 17 5 The Bell theorem 19 5.1 Bell's Inequality . 19 5.2 Derivation . 19 5.3 Violation by quantum mechanics . 21 5.4 CHSH inequality . 22 5.5 Bell's theorem and further discussion . 24 5.6 Different assumptions . 26 6 Experimental realizations and loopholes 26 7 Causality 29 7.1 Causality in Special Relativity . 30 7.2 Causality and Quantum Mechanics . 33 7.3 Remarks and prospects . 34 8 Acknowledgment 35 1 1 Motivation and Mathematical framework In recent years, many physicists have taken the incompatibility between cer- tain notions of causality, reality, locality and the empirical data less and less as a philosophical discussion about interpretational ambiguities. Instead sci- entists started to regard this tension as a productive resource for new ideas about quantum entanglement, quantum computation, quantum cryptogra- phy and quantum information. This becomes especially apparent looking at the number of citations of the original EPR paper, which has risen enormously over recent years, and be- coming the starting point for many groundbreaking ideas. -

What Can Quantum Optics Say About Computational Complexity Theory?

week ending PRL 114, 060501 (2015) PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS 13 FEBRUARY 2015 What Can Quantum Optics Say about Computational Complexity Theory? Saleh Rahimi-Keshari, Austin P. Lund, and Timothy C. Ralph Centre for Quantum Computation and Communication Technology, School of Mathematics and Physics, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia (Received 26 August 2014; revised manuscript received 13 November 2014; published 11 February 2015) Considering the problem of sampling from the output photon-counting probability distribution of a linear-optical network for input Gaussian states, we obtain results that are of interest from both quantum theory and the computational complexity theory point of view. We derive a general formula for calculating the output probabilities, and by considering input thermal states, we show that the output probabilities are proportional to permanents of positive-semidefinite Hermitian matrices. It is believed that approximating permanents of complex matrices in general is a #P-hard problem. However, we show that these permanents can be approximated with an algorithm in the BPPNP complexity class, as there exists an efficient classical algorithm for sampling from the output probability distribution. We further consider input squeezed- vacuum states and discuss the complexity of sampling from the probability distribution at the output. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.060501 PACS numbers: 03.67.Ac, 42.50.Ex, 89.70.Eg Introduction.—Boson sampling is an intermediate model general formula for the probabilities of detecting single of quantum computation that seeks to generate random photons at the output of the network. Using this formula we samples from a probability distribution of photon (or, in show that probabilities of single-photon counting for input general, boson) counting events at the output of an M-mode thermal states are proportional to permanents of positive- linear-optical network consisting of passive optical ele- semidefinite Hermitian matrices. -

Many Worlds Model Resolving the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox Via a Direct Realism to Modal Realism Transition That Preserves Einstein Locality

Many Worlds Model resolving the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox via a Direct Realism to Modal Realism Transition that preserves Einstein Locality Sascha Vongehr †,†† †Department of Philosophy, Nanjing University †† National Laboratory of Solid-State Microstructures, Thin-film and Nano-metals Laboratory, Nanjing University Hankou Lu 22, Nanjing 210093, P. R. China The violation of Bell inequalities by quantum physical experiments disproves all relativistic micro causal, classically real models, short Local Realistic Models (LRM). Non-locality, the infamous “spooky interaction at a distance” (A. Einstein), is already sufficiently ‘unreal’ to motivate modifying the “realistic” in “local realistic”. This has led to many worlds and finally many minds interpretations. We introduce a simple many world model that resolves the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. The model starts out as a classical LRM, thus clarifying that the many worlds concept alone does not imply quantum physics. Some of the desired ‘non-locality’, e.g. anti-correlation at equal measurement angles, is already present, but Bell’s inequality can of course not be violated. A single and natural step turns this LRM into a quantum model predicting the correct probabilities. Intriguingly, the crucial step does obviously not modify locality but instead reality: What before could have still been a direct realism turns into modal realism. This supports the trend away from the focus on non-locality in quantum mechanics towards a mature structural realism that preserves micro causality. Keywords: Many Worlds Interpretation; Many Minds Interpretation; Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox; Everett Relativity; Modal Realism; Non-Locality PACS: 03.65. Ud 1 1 Introduction: Quantum Physics and Different Realisms ............................................................... -

Hidden Variables and the Two Theorems of John Bell

Hidden Variables and the Two Theorems of John Bell N. David Mermin What follows is the text of my article that appeared in Reviews of Modern Physics 65, 803-815 (1993). I’ve corrected the three small errors posted over the years at the Revs. Mod. Phys. website. I’ve removed two decorative figures and changed the other two figures into (unnumbered) displayed equations. I’ve made a small number of minor editorial improvements. I’ve added citations to some recent critical articles by Jeffrey Bub and Dennis Dieks. And I’ve added a few footnotes of commentary.∗ I’m posting my old paper at arXiv for several reasons. First, because it’s still timely and I’d like to make it available to a wider audience in its 25th anniversary year. Second, because, rereading it, I was struck that Section VII raises some questions that, as far as I know, have yet to be adequately answered. And third, because it has recently been criticized by Bub and Dieks as part of their broader criticism of John Bell’s and Grete Hermann’s reading of John von Neumann.∗∗ arXiv:1802.10119v1 [quant-ph] 27 Feb 2018 ∗ The added footnotes are denoted by single or double asterisks. The footnotes from the original article have the same numbering as in that article. ∗∗ R¨udiger Schack and I will soon post a paper in which we give our own view of von Neumann’s four assumptions about quantum mechanics, how he uses them to prove his famous no-hidden-variable theorem, and how he fails to point out that one of his assump- tions can be violated by a hidden-variables theory without necessarily doing violence to the whole structure of quantum mechanics. -

Quantum Error Correction

Quantum Error Correction Sri Rama Prasanna Pavani [email protected] ECEN 5026 – Quantum Optics – Prof. Alan Mickelson - 12/15/2006 Agenda Introduction Basic concepts Error Correction principles Quantum Error Correction QEC using linear optics Fault tolerance Conclusion Agenda Introduction Basic concepts Error Correction principles Quantum Error Correction QEC using linear optics Fault tolerance Conclusion Introduction to QEC Basic communication system Information has to be transferred through a noisy/lossy channel Sending raw data would result in information loss Sender encodes (typically by adding redundancies) and receiver decodes QEC secures quantum information from decoherence and quantum noise Agenda Introduction Basic concepts Error Correction principles Quantum Error Correction QEC using linear optics Fault tolerance Conclusion Two bit example Error model: Errors affect only the first bit of a physical two bit system Redundancy: States 0 and 1 are represented as 00 and 01 Decoding: Subsystems: Syndrome, Info. Repetition Code Representation: Error Probabilities: 2 bit flips: 0.25 *0.25 * 0.75 3 bit flips: 0.25 * 0.25 * 0.25 Majority decoding Total error probabilities: With repetition code: Error Model: 0.25^3 + 3 * 0.25^2 * 0.75 = 0.15625 Independent flip probability = 0.25 Without repetition code: 0.25 Analysis: 1 bit flip – No problem! Improvement! 2 (or) 3 bit flips – Ouch! Cyclic system States: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Operators: Error model: probability = where q = 0.5641 Decoding Subsystem probability -

Lessons of Bell's Theorem

Lessons of Bell's Theorem: Nonlocality, yes; Action at a distance, not necessarily. Wayne C. Myrvold Department of Philosophy The University of Western Ontario Forthcoming in Shan Gao and Mary Bell, eds., Quantum Nonlocality and Reality { 50 Years of Bell's Theorem (Cambridge University Press) Contents 1 Introduction page 1 2 Does relativity preclude action at a distance? 2 3 Locally explicable correlations 5 4 Correlations that are not locally explicable 8 5 Bell and Local Causality 11 6 Quantum state evolution 13 7 Local beables for relativistic collapse theories 17 8 A comment on Everettian theories 19 9 Conclusion 20 10 Acknowledgments 20 11 Appendix 20 References 25 1 Introduction 1 1 Introduction Fifty years after the publication of Bell's theorem, there remains some con- troversy regarding what the theorem is telling us about quantum mechanics, and what the experimental violations of Bell inequalities are telling us about the world. This chapter represents my best attempt to be clear about what I think the lessons are. In brief: there is some sort of nonlocality inherent in any quantum theory, and, moreover, in any theory that reproduces, even approximately, the quantum probabilities for the outcomes of experiments. But not all forms of nonlocality are the same; there is a distinction to be made between action at a distance and other forms of nonlocality, and I will argue that the nonlocality needed to violate the Bell inequalities need not involve action at a distance. Furthermore, the distinction between forms of nonlocality makes a difference when it comes to compatibility with relativis- tic causal structure. -

PROPOSED EXPERIMENT to TEST LOCAL HIDDEN-VARIABLE THEORIES* John F

VOLUME 23, NUMBER 15 PHYSI CA I. REVIEW I.ETTERS 13 OcToBER 1969 sible without the devoted effort of the personnel ~K. P. Beuermann, C. J. Rice, K. C. Stone, and R. K. of the Orbiting Geophysical Observatory office Vogt, Phys. Rev. Letters 22, 412 (1969). at the Goddard Space Flight Center and at TR%. 2J. L'Heureux and P. Meyer, Can. J. Phys. 46, S892 (1968). 3J. Rockstroh and W. R. Webber, University of Min- nesota Publication No. CR-126, 1969. ~Research supported in part under National Aeronau- 46. M. Simnett and F. B. McDonald, Goddard Space tics and Space Administration Contract No. NAS 5-9096 Plight Center Report No. X-611-68-450, 1968 (to be and Grant No. NGR 14-001-005. published) . )Present address: Department of Physics, The Uni- 5W. R. Webber, J. Geophys. Res. 73, 4905 (1968). versity of Arizona, Tucson, Ariz. GP. B. Abraham, K. A. Brunstein, and T. L. Cline, (Also Department of Physics. Phys. Rev. 150, 1088 (1966). PROPOSED EXPERIMENT TO TEST LOCAL HIDDEN-VARIABLE THEORIES* John F. Clauserf Department of Physics, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027 Michael A. Horne Department of Physics, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 and Abner Shimony Departments of Philosophy and Physics, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 and Richard A. Holt Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 (Received 4 August 1969) A theorem of Bell, proving that certain predictions of quantum mechanics are incon- sistent with the entire family of local hidden-variable theories, is generalized so as to apply to realizable experiments. A proposed extension of the experiment of Kocher and Commins, on the polarization correlation of a pair of optical photons, will provide a de- cisive test betw'een quantum mechanics and local hidden-variable theories. -

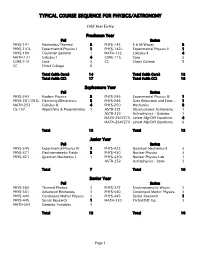

Typical Course Sequence for Physics/Astronomy

TYPICAL COURSE SEQUENCE FOR PHYSICS/ASTRONOMY Odd Year Entry Freshman Year Fall Spring PHYS-141 Mechanics/Thermal 3 PHYS-142 E & M/Waves 3 PHYS-141L Experimental Physics I 1 PHYS-142L Experimental Physics II 1 PHYS-190 Freshman Seminar 1 MATH-132 Calculus II 4 MATH-131 Calculus I 4 CORE-115 Core 5 CORE-110 Core 5 CC Christ College 8 CC Christ College 8 Total (with Core) 14 Total (with Core) 13 Total (with CC) 17 Total (with CC) 16 Sophomore Year Fall Spring PHYS-243 Modern Physics 3 PHYS-245 Experimental Physics III 1 PHYS-281/281L Electricity/Electronics 3 PHYS-246 Data Reduction and Error... 1 MATH-253 Calculus III 4 PHYS-250 Mechanics 3 CS-157 Algorithms & Programming 3 ASTR-221 Observational Astronomy 1 ASTR-253 Astrophysics - Galaxies 3 MATH-260/270 Linear Alg/Diff Equations 4 MATH-264/270 Linear Alg/Diff Equations 6 Total 13 Total 13 Junior Year Fall Spring PHYS-345 Experimental Physics IV 1 PHYS-422 Quantum Mechanics II 3 PHYS-371 Electromagnetic Fields 3 PHYS-430 Nuclear Physics 3 PHYS-421 Quantum Mechanics I 3 PHYS-430L Nuclear Physics Lab 1 ASTR-252 Astrophysics - Stars 3 Total 7 Total 10 Senior Year Fall Spring PHYS-360 Thermal Physics 3 PHYS-372 Electromagnetic Waves 3 PHYS-381 Advanced Mechanics 3 PHYS-440 Condensed Matter Physics 3 PHYS-440 Condensed Matter Physics 3 PHYS-445 Senior Research 1 PHYS-445 Senior Research 1 MATH-330 Partial Diff. Eq. 3 MATH-334 Complex Variables 3 Total 13 Total 10 Page 1 TYPICAL COURSE SEQUENCE FOR PHYSICS/ASTRONOMY Even Year Entry Freshman Year Fall Spring PHYS-141 Mechanics/Thermal 3 PHYS-142 E & M/Waves 3 PHYS-141L Experimental Physics I 1 PHYS-142L Experimental Physics II 1 PHYS-190 Freshman Seminar 1 MATH-132 Calculus II 4 MATH-131 Calculus I 4 CORE-115 Core 5 CORE-110 Core 5 CC Christ College 8 CC Christ College 8 Total (with Core) 14 Total (with Core) 13 Total (with CC) 17 Total (with CC) 16 Sophomore Year Fall Spring PHYS-243 Modern Physics 3 PHYS-245 Experimental Physics III 1 PHYS-281 Electricity/Electronics 3 PHYS-250 Mechanics 3 MATH-253 Calculus III 4 PHYS-246 Data Reduction and Error..