Booklet of Advance Readings for Lectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

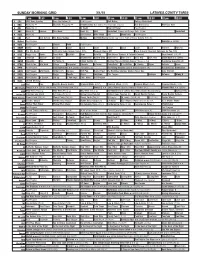

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

The Matter of Britain

THE MATTER OF BRITAIN: KING ARTHUR'S BATTLES I had rather myself be the historian of the Britons than nobody, although so many are to be found who might much more satisfactorily discharge the labour thus imposed on me; I humbly entreat my readers, whose ears I may offend by the inelegance of my words, that they will fulfil the wish of my seniors, and grant me the easy task of listening with candour to my history May, therefore, candour be shown where the inelegance of my words is insufficient, and may the truth of this history, which my rustic tongue has ventured, as a kind of plough, to trace out in furrows, lose none of its influence from that cause, in the ears of my hearers. For it is better to drink a wholesome draught of truth from a humble vessel, than poison mixed with honey from a golden goblet Nennius CONTENTS Chapter Introduction 1 The Kinship of the King 2 Arthur’s Battles 3 The River Glein 4 The River Dubglas 5 Bassas 6 Guinnion 7 Caledonian Wood 8 Loch Lomond 9 Portrush 10 Cwm Kerwyn 11 Caer Legion 12 Tribuit 13 Mount Agned 14 Mount Badon 15 Camlann Epilogue Appendices A Uther Pendragon B Arthwys, King of the Pennines C Arthur’s Pilgrimages D King Arthur’s Bones INTRODUCTION Cupbearer, fill these eager mead-horns, for I have a song to sing. Let us plunge helmet first into the Dark Ages, as the candle of Roman civilisation goes out over Europe, as an empire finally fell. The Britons, placid citizens after centuries of the Pax Romana, are suddenly assaulted on three sides; from the west the Irish, from the north the Picts & from across the North Sea the Anglo-Saxons. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

NEW RESUME Current-9(5)

DEEDEE BRADLEY CASTING DIRECTOR [email protected] 818-980-9803 X2 TELEVISION PILOTS * Denotes picked up for series SWITCHED AT BIRTH* One hour pilot for ABC Family 2010 Executive Producers: Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin Director: Steve Miner BEING HUMAN* One hour pilot for Muse Ent./SyFy 2010 Executive Producers: Jeremy Carver, Anna Fricke, Michael Prupas Director: Adam Kane UNTITLED JUSTIN ADLER PILOT Half hour pilot for Sony/NBC 2009 Executive Producers: Eric Tannenbaum, Kim Tannenbaum, Mitch Hurwitz, Joe Russo, Anthony Russo, Justin Adler, David Guarascio, Moses Port Directors: Joe Russo and Anthony Russo PARTY DOWN * Half hour pilot for STARZ Network 2008 Executive Producers: Rob Thomas, Paul Rudd Director: Rob Thomas BEVERLY HILLS 90210* One hour pilot for CBS/Paramount and CW Network. Executive Producers: Gabe Sachs, Jeff Judah, Mark Piznarski, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski MERCY REEF aka AQUAMAN One hour pilot for Warner Bros./CW 2006 Executive Producers: Miles Millar, Al Gough, Greg Beeman Director : Greg Beeman Shared casting..Joanne Koehler VERONICA MARS* One hour pilot for Stu Segall Productions/UPN 2004 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski SAVING JASON Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./WBN 2003 Executive Producer: Winifred Hervey Director: Stan Lathan NEWTON One hour pilot for Warner Bros/UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Gregory Noveck, Craig Silverstein Director: Lesli Linka Glatter ROCK ME BABY* Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Tony Krantz, Tim Kelleher -

Euriskodata Rare Book Series

Jsl THE ANTIQUITIES OF AEEAN. *. / f?m Finfcal's and Bruce's Cave. THE ANTIQUITIES OF ARRAN: Skekjj of fyt EMBRACING AN ACCOUNT OP THE SUDEEYJAE UNDER THE NOESEMEN, BY JOHN M'ARTHUR ' Enquire, I pray thee, of the former age, and prepare thyself to the search of their fathers : for we are but of yesterday." JOB viii. 8, 9. ames acr, n. GLASGOW: THOMAS MUKRAY AND SON. EDINBURGH: PATON AND RITCHIE. LONDON: ARTHUR HALL, VIRTUE AND co. 1861. PREFATORY NOTE. WHILST spending a few days in Arran, the attention of the Author was drawn to the numerous pre-historic monuments scattered over the Island. The present small Work embraces an account of these in- teresting remains, prepared chiefly from careful personal observation. The concluding Part contains a description of the monu- ments of a later period the chapels and castles of the Island to which a few brief historical notices have been appended. Should the persual of these pages induce a more thorough investigation into these stone-records of the ancient history of Arran, the object of the Author shall have been amply attained. The Author begs here gratefully to acknowledge the kind- ness and assistance rendered him by JOHN BUCHANAN, Esq. of Glasgow; JAMES NAPIEE, Esq., F.C.S., &c., Killin; the Rev. COLIN F. CAMPBELL of Kilbride, and the Rev. CHARLES STEWART, Kilmorie Arran. 4 RADNOB TERBACE, GLASGOW, June, 1861. 2058000 CONTENTS. Page PREFATORY NOTE, 5 i|u Stair* CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION, .... ..... 11 " II. BARROWS AND CAIRNS, ....... 18 " III. CROMLECHS, .......... 37 IV. STANDING STONES, ........ 42 " V. STONE CIRCLES, ........ -

St Kentigern

St. Kentigern St. Kentigern, was born c. 518. According to the Life of Saint Mungo written by the monk, Jocelin of Furness, in about 1185, Mungo’s mother was Princess Theneva, the daughter of King Loth (Lleuddun), who ruled in the area of, what is today, East Lothian. Theneva became pregnant - accounts vary as to whether she was raped by, or had an illicit relationship with, Owain mab Urien, her cousin, who was King of North Rheged (now part of Galloway). Her father, who was furious at his daughter’s pregnancy outside of marriage, had her thrown from the heights of Traprain Law. Tradition has it that, believing her to be a witch, local people cast her adrift on the River Forth in a coracle without oars, where she drifted upstream before coming ashore at Culross in Fife. It was here that her son, Kentigern, was born. Kentigern was given the name Mungo, meaning something similar to ‘dear one’, by St. Serf, who ran a monastery at Culross, and who took both Theneva and her son into his care. St. Serf went on to supervise Mungo’s upbringing. At the age of 25, Mungo began his missionary work on the banks of the River Clyde, where he built a church close to the Molendinar Burn. The site of his early church formed part of Glasgow Cathedral. Mungo worked on the banks of the River Clyde for 13 years, living an austere monastic life and making many converts by his holy example and preaching. However, a strong anti-Christian movement headed by King Morken of Strathclyde drove him out. -

The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow

Servants to St. Mungo: The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow by Daniel MacLeod A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Daniel MacLeod, May, 2013 ABSTRACT SERVANTS TO ST MUNGO: THE CHURCH IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY GLASGOW Daniel MacLeod Advisors: University of Guelph, 2013 Dr. Elizabeth Ewan Dr. Peter Goddard This thesis investigates religious life in Glasgow, Scotland in the sixteenth century. As the first full length study of the town’s Christian community in this period, this thesis makes use of the extant Church documents to examine how Glaswegians experienced Christianity during the century in which religious change was experienced by many communities in Western Europe. This project includes research from both before and after 1560, the year of the Reformation Parliament in Scotland, and therefore eschews traditional divisions used in studies of this kind that tend to view 1560 as a major rupture for Scotland’s religious community. Instead, this study reveals the complex relationships between continuity and change in Glasgow, showing a vibrant Christian community in the early part of the century and a changed but similarly vibrant community at the century’s end. This project attempts to understand Glasgow’s religious community holistically. It investigates the institutional structures of the Church through its priests and bishops as well as the popular devotions of its parishioners. It includes examinations of the sacraments, Church discipline, excommunication and religious ritual, among other Christian phenomena. The dissertation follows many of these elements from their medieval Catholic roots through to their Reformed Protestant derivations in the latter part of the century, showing considerable links between the traditions. -

College in 1967. the Purposes Were to Provide the Trainees

OCLOIENT SES1112 ED 032 552 cc 004 229 ay-Ayers. George E.. Ed Rehabilitating the Culturally Disadvantageil. Rehabilitation Services Administration (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Pub Date 16 Aug 67 Note-140p_; Report of a Regional Conferenceon Rehabilitating the Culturally Disadvantaged held at Mankato State College. Mankato. Minnesota. August 16-18. 1967 EDRS Price MF -S0.75 HC -S7.10 Descriptors- Culturaily Disadvantaged. Disadvantaged Environment. DisadvantagedYouth. Indians. Program Descriptions. Rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Programs. Vocational Rehabilitation A conference on rehabilitating the culturally disadvantagedwas held at Mankato College in 1967. The purposeswere to provide the trainees (1) the essential information relative to the characteriQtics and problems of.as well as the methods for. rehabilitating the culturally deprived; (2)an opportunity to cooperatively develop criteria for utilization by state vocational rehabilitation agencies in diagnosing cultural deprivation; and (3) an opportunity to delineate and develop procedures for increasingtheprovision of vocationrehabilitationservicestotheculturally disadvantaged. The four sections of the report deal with the followingareas: (1) rehabilitating the culturally deprived. (2) approachesto rehabilitating the culturally deprived. (3) representative rehabilitationprograms for the culturally disadvantaged. and (4) summary reports of workshop sessions. Topics discussedinclude: (1) preparingdiagnosticiansforworkingwiththeculturallydisadvantaged.(2) communicating with the culturally -

The Casting Director Guide from Now Casting, Inc

The Casting Director Guide From Now Casting, Inc. This printable Casting Director Guide includes CD listings exported from the CD Connection in NowCasting.com’s Contacts NOW area. The Guide is an easy way to get familiar with all the CD’s. Or, you might want to print a copy that lives in your car. Keep in mind that the printable CD Guide is created approximately once a month while the CD Connection is updated constantly. There will be info in the printable “Guide” that is out of date almost immediately… that’s the nature of casting. If you need a more comprehensive, timely and searchable research and marketing tool then you should consider using Contacts NOW in NowCasting.com. In Contacts NOW, you can search the CD database directly, make personal notes, create mailing lists, search Agents, make your own Custom Contacts and print labels. You can even export lists into Postcards NOW – a service that lets you create and mail postcards all from your desktop! You will find Contacts NOW in your main NowCasting menu under Get it NOW or Guides and Labels. Questions? Contact the NowCasting Staff @ 818-841-7165 Now Casting.com We’re Back! Many post hiatus updates! October ‘09 $13.00 Casting Director Guide Run BY Actors FOR Actors More UP- TO-THE-MINUTE information than ANY OTHER GUIDE Compare to the others with over 100 pages of information Got Casting Notices? We do! www.nowcasting.com WHY BUY THIS BOOK? Okay, there are other books on the market, so why should you buy this one? Simple. -

Tooele Transcript Bulletin, Published Every Tuesday and Thursday in This Newspaper

FRONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY Family delivers livestock for Bit N’ Spur Rodeo TOOELE See B1 TRANSCRIPT BULLETIN July 8, 2008 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 115 NO. 015 50¢ Justice courts consolidated Judge William Pitt given $30,000 raise to head up countywide system by Jamie Belnap the Tooele Valley Justice Court. STAFF WRITER “The county was faced with two possible options,” said Tooele The Tooele Valley Justice Court County Attorney Doug Hogan, has taken over administration of who was asked by the commission Wendover’s justice court in a move to look into the situation and pres- designed to consolidate operations ent them with the best possible under one judge. solution. “Either replace Judge With the recent retirement of Melville and keep two justice court Wendover Justice Court Judge judges on the payroll, or combine LaMar Melville, Tooele County them and have one judge serve the Commissioners elected to add the entire county.” Justice courts have small Wendover court into a newly the authority to deal with class B created Tooele County Justice and C misdemeanors, violations Court rather than appoint a new of ordinances, small claims, and judge in Wendover. The new court infractions committed within their will be headed by Judge William Pitt, who was serving as judge for SEE COURTS PAGE A5 ➤ photography / Maegan Burr Col. Yolanda Dennis-Lowman receives the depot flag from Commander Gen. James Rogers Tuesday morning at the Tooele Army Depot change-of-command ceremony. Dennis-Lowman will be stationed at TEAD for up to three years. New commander takes over depot by Jamie Belnap Davis, who headed the depot expected to lead the facility’s National War College. -

Contemporary Institutional and Popular Frameworks for Gender Variance

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Anthropology Theses Department of Anthropology 4-21-2010 "They Need Labels": Contemporary Institutional and Popular Frameworks for Gender Variance Ophelia Bradley Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses Recommended Citation Bradley, Ophelia, ""They Need Labels": Contemporary Institutional and Popular Frameworks for Gender Variance." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses/35 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THEY NEED LABELS”: CONTEMPORARY INSTITUTIONAL AND POPULAR FRAMEWORKS FOR GENDER VARIANCE by OPHELIA D. BRADLEY Under the Direction of Dr. Jennifer Patico ABSTRACT This study addresses the complex issues of etiology and conceptualization of gender variance in the modern West. By analyzing medical, psychological, and popular approaches to gender variance, I demonstrate the highly political nature of each of these paradigms and how gender variant individuals engage with these discourses in the elaboration of their own gender identities. I focus on the role of institutional authority in shaping popular ideas about gender variance and the relationship of gender variant individuals who seek medical intervention towards the systems that regulate their care. Also relevant are the tensions between those who view gender variance as an expression of an essential cross-sex gender (as in traditional transsexual narrative) and those who believe that gender is socially constructed and non-binary. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts LYRICAL STRATEGIES: the POETICS of the TWENTIE

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts LYRICAL STRATEGIES: THE POETICS OF THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN NOVEL A Dissertation in English by Katie Owens-Murphy Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 The dissertation of Katie Owens-Murphy was reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert L. Caserio Professor of English Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Kathryn Hume Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee John L. Selzer Professor of English Kathryn M. Grossman Professor of French Garrett A. Sullivan, Jr. Professor of English and Director of Graduate Studies Robin Schulze Professor of English The University of Delaware Special Member Brian McHale Humanities Distinguished Professor of English The Ohio State University Special Member *Signatures are on file at the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT Lyrical Strategies: The Poetics of the Twentieth-Century American Novel takes a comparative approach to genre by examining twentieth-century American novels in relation to the lyric, rather than the narrative, tradition. Narrative theorists have long noted that modern and contemporary novels paradoxically abandon the defining characteristics of narrative—plot, sequence, external action—for other rhetorical strategies. I argue for a strain of the twentieth-century American novel that is better suited to the reading practices of lyric poetry, in which we read not for story but for structural repetition,