The Battle Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meurthe-Et-Moselle

Dernier rafraichissement le 02/10/21 Liste des entreprises de transport routier de MARCHANDISES immatriculées au registre national Pour effectuer une recherche d'entreprise (ou de commune), pressez et maintenez la touche "Ctrl" tout en appuyant sur la touche "F". Saisissez alors tout ou partie du mot recherché. *LTI : Licence Transport Intérieur **LC : Licence Communautaire MEURTHE ET MOSELLE Date de Date de Nombre Date de Date de Nombre Code Siège Gestionnaire Numéro début de fin de de copies Numéro début de fin de de copies SIRET Raison sociale Catégorie juridique Commune Postal (O/N) de transport LTI* validité validité LTI LC** validité validité LC LTI LTI valides LC LC valides CAZALS 2018 44 79080877800019 2 B TRANSPORT Autre société à responsabilité limitée 54600 VILLERS-LES-NANCY O 01/07/2018 31/07/2023 3 0 BASTIEN JEAN 0000841 BOUVERY CIREY-SUR- 2019 44 85060616100014 AB TRANSPORT BOIS Société par actions simplifiée (SAS) 54480 O MANUEL 0 14/05/2019 31/12/2024 2 VEZOUZE 0000586 MARC RENE MOINARD 2020 44 89113784600012 ACME TRANSPORT Société par actions simplifiée (SAS) 54000 NANCY O 10/12/2020 31/07/2022 23 0 CHRISTOPHE 0001178 D'ELLENA 2020 44 52343031200034 ACR TRANSPORT Autre société à responsabilité limitée 54760 MOIVRONS O FABIEN 0 01/08/2020 31/07/2025 40 0000439 PATRICE Société par actions simplifiée à associé FERSTLER VANDOEUVRE-LES- 2017 44 45313102100017 ACTIFRAIS SAS unique ou société par actions simplifiée 54500 O MICHEL 0 01/07/2017 31/07/2022 6 NANCY 0000983 unipersonnelle ROGER ACTIF TRANSDEM VANDOEUVRE-LES- YASSINE -

The International Labour Organization and the Quest for Social Justice, 1919–2009

The International Labour Organization and the quest for social justice, 1919–2009 The International Labour Organization and the quest for social justice, 1919–2009 Gerry Rodgers, Eddy Lee, Lee Swepston and Jasmien Van Daele INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE GENEVA Copyright © International Labour Organization 2009 First published in paperback in 2009 by the International Labour Office, CH-1211, Geneva 22, Switzerland First published in hardback in 2009 by Cornell University Press, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, NY 14850, United States (available for sale in North America only) Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copy- right Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. The International Labour Organization and the quest for social justice, 1919–2009 Gerry Rodgers, Eddy Lee, Lee Swepston and Jasmien Van Daele International Labour Office. – Geneva: ILO, 2009 ISBN 978-92-2-121955-2 (paperback) ILO / role of ILO / ILO standard setting / tripartism / workers rights / quality of working life / social security / promotion of employment / poverty alleviation / decent work / history / trend 01.03.7 Also available in hardback: The International Labour Organization and the quest for social justice, 1919–2009 (ISBN 978-0-8014-4849-2), Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2009. -

"OPERATIONS OP the 65Th ARTILLERY O.A.O. with the FRENCH XVII ARMY CORPS."

ha-c GROUP R0BAROH. Group IX SubJ«ot% "OPERATIONS OP THE 65th ARTILLERY O.A.O. WITH THE FRENCH XVII ARMY CORPS." By Willla-a F, Marquat captain O.A.C.(DOL) I I Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 May, 1935 j MEMORANDUM FOR: The Directorf aeoond Year Glass, The Oommand and General Staff bohool, ^ort L#avenworth# dUBJBOT: Operations of the 65th Artillery, C*A.C, with tho XVII French Army Corps. 1. PAPERS ACUOMPAN11.,G: i 1. A Bibliography for this study. 2. tracing of a map showing the operations of the French XVII Corps and a diagranatio repre« sentation of the operations of the 65th ArtiL lery, in this action• I note: Other than tha tthe 65th Artillery C.A.C. i actually participated in this engagement, there is little j j Information available from official sources• borne of the j dLata presented is from personal records which necea&arily are uncorroborated* Reference is made to such personal records when used in this document. II THE STUDY PRESENTED*— Operations of the 65th Artillery, O.A.C. with the XVII Corps (French) during the period 7 to 25 October 1918. III. HISTORICAL PACTS RELATING TO THE SUBJECT. Forces t XVII French Army corps: Fro15tmh Colonialeft tol righDivisiont , drench 10th Colonial Division, French (X) A29 - PP 2 and 3 SIA - Chap V, Part 5 AAEC - pp 293-295 incl. 33EAEF - pp 5 and 6 H33D - P 5 * Pagea of this document are not numbered. Page 26 DI (Prenoh) 18 DI {Prenoh) 58th Brigade^ 29th Division ( U.S.) 33rd Division, less detachments (U.S.) Artillery: 158th Field Artillery Brigade lattaohed) 65th Artillery O.A.O., lest 3rd -

1779 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Kyllonen

1779 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Kyllonen pation, farmer; inducted at Hillsboro on April 29, 1918; sent to Camp Dodge, Iowa; served in Company K, 350th Infantry, to May 16, 1918; Com- pany K, 358th Infantry, to discharge; overseas from June 20, 1918, to June 7, 1919. Engagements: Offensives: St. Mihiel; Meuse-Argonne. De- fensive Sectors: Puvenelle and Villers-en-Haye (Lorraine). Discharged at Camp Dodge, Idwa, on June 14, 1919, as a Private. KYLLONEN, CHARLEY. Army number 4,414,704; registrant, Nelson county; born, Brocket, N. Dak., July 5, 1894, of Finnish parents; occu- pation, farmer; inducted at La,kota on Sept. 3, 1918; sent to Camp Grant, Ill.; served in Machine Gun Training Center, Camp Hancock, Ga., to dis- charge. Discharged at Camp Hancock, Ga., on March 26, 1919, as a Private. KYLMALA, AUGUST. Army number 2,110,746; registrant, Dickey county; born, Oula, Finland, Aug. 9, 1887; naturalized citizen; occupation, laborer; inducted at Ellendale on Sept. 21, 1917; sent. to Camp Dodge, Iowa; served in Company I, 352nd Infantry, to Nov. 28, 1917; Company L, 348th Infantry, to May 18, 1918; 162nd Depot Brigade, to June 17, 1918; 21st Battalion, M. S. Gas Company, to Aug. 2, 1918; 165th Depot Brigade, to discharge. Discharged at Camp Travis, Texas, on Dec. 4, 1918, as a Private. KYNCL, JOHN. Army number 298,290; registrant, Cavalier county; born, Langdon, N. Dak., March 27, 1896, of Bohemian parents; occupation, farmer; inducted at Langdon on Dec. 30, 1917; sent to Fort Stevens, Ore.; served in Battery D, 65th Artillery, Coast Artillery Corps, to discharge; overseas from March 25, 1918, to Jan. -

The Geopolitics of Laïcité in a Multicultural Age: French Secularism, Educational Policy and the Spatial Management of Difference

The Geopolitics of Laïcité in a Multicultural Age: French Secularism, Educational Policy and the Spatial Management of Difference Christopher A. Lizotte A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Katharyne Mitchell, Chair Victoria Lawson Michael Brown Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Geography ©Copyright 2017 Christopher A. Lizotte University of Washington Abstract The Geopolitics of Laïcité in a Multicultural Age: French Secularism, Educational Policy and the Spatial Management of Difference Christopher A. Lizotte Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Katharyne Mitchell Geography I examine a package of educational reforms enacted following the January 2015 attacks in and around Paris, most notably directed at the offices of the satirical publication Charlie Hebdo. These interventions, known collectively as the “Great Mobilization for the Republic’s Values”, represent the latest in a string of educational attempts meant to reinvigorate a sense of national pride among immigrant-descended youth – especially Muslim – in France’s unique form of state secularism, laïcité. While ostensibly meant to apply equally across the nationalized French school system, in practice La Grande Mobilisation has been largely enacted in schools located in urban spaces of racialized difference thought to be “at risk” of anti-republican behavior. Through my work, I show that practitioners exercise their own power by subverting and adapting geopolitical discourses running through educational laïcité – notably global security, women’s rights, and communalism – are nuanced by school-based practitioners, who interpret state directives in the light of their institutional knowledge and responsiveness to the social and economic profiles of their student populations. -

2015-0000003

LETTRE CIRCULAIRE n° 2015-0000003 GRANDE DIFFUSION Réf Classement 1.023.0 Montreuil, le 07/01/2015 07/01/2015 DIRECTION DE LA OBJET REGLEMENTATION DU RECOUVREMENT ET DU Modification du champ d'application du versement transport SERVICE (art. L. 2333-64 et s. du Code Général des Collectivités GESTION DES OUTILS ET Territoriales) BASES DOCUMENTAIRES Texte à annoter : LCIRC-2014-016 ; 2010-075 Affaire suivie par : NA/PM A compter du 1er janvier 2015, le périmètre de transports urbains de la Communauté de Communes du BASSIN DU PONT-A- MOUSSON est étendu aux communes de BOUXIERES-SOUS- FROIDMONT, CHAMPEY-SUR-MOSELLE, LESMENILS, VITTONVILLE, AUTREVILLE-SUR-MOSELLE, BEZAUMONT, LANDREMONT, LOISY, SAINTE-GENEVIEVE, VILLE-AU-VAL, DIEULOUARD, GEZONCOURT, GRISCOURT, ROGEVILLE, ROSIERES-EN-HAYE, VILLERS-EN-HAYE, BELLEVILLE, MARTINCOURT, VANDIERES, PAGNY-SUR-MOSELLE et VILLERS-SOUS-PRENY A compter du 1er janvier 2015, le taux de versement transport applicable sur le territoire de ces communes est porté à 0,60 % Par un arrêté du 8 décembre 2014, la Préfecture de Meurthe-et-Moselle a autorisé l'adhésion des communes de BOUXIERES-SOUS- FROIDMONT, CHAMPEY-SUR-MOSELLE, LESMENILS, VITTONVILLE, AUTREVILLE, BEZAUMONT, LANDREMONT, LOISY, SAINTE-GENEVIEVE, VILLE-AU-VAL, DIEULOUARD, GEZONCOURT, GRISCOURT, ROGEVILLE, ROSIERES-EN-HAYE, VILLERS-EN- HAYE, BELLEVILLE, MARTINCOURT, VANDIERES, PAGNY-SUR- MOSELLE et VILLERS-SOUS-PRENY à la Communauté de Communes du BASSIN DE PONT-A-MOUSSON (9305403). Le périmètre de transports urbains de l'Autorité organisatrice de transport (AOT) est ainsi étendu au territoire de ces communes à compter du 1er janvier 2015. A compter du 1er janvier 2015, le versement transport est applicable sur le territoire de ces communes au taux en vigueur au sein de la Communauté de Communes du BASSIN DE PONT-A-MOUSSON, soit 0,60 % Les informations relatives au champ d'application, aux taux, au recouvrement et au reversement du versement transport sont regroupées dans le tableau ci-joint. -

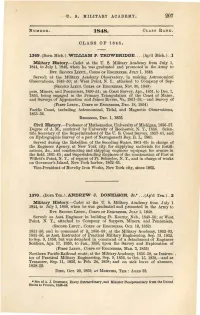

Class of 1848-1850

U. S. MILITARY ACADEl\[Y. 207 NUMBER. 1848. CLASS RANK. CLASS OF 1848. 1369. (Born Mich.). WILLIAM P. TROWBRIDGE .... (Ap'd Mich.) ..1 Military History.- Cadet at the U. S. Military Academy from July I, 1844, to July 1, 1848, when he was graduated and promoted in t.he Army to Bn. SECOND LIEUT., CORPS OF ENGI~'EERS, JULY i, 1848. Served: at the Milit.ary Academy Observatory, in making Ast.ronomical Observations, 1848- 50; at West Point, N. Y., attached to Company of Snp (SECOND LIEUT. CORPS OF ENGINEERS, Nov. 30, 1849) pel's. Minel'S, and Pontoniers, 1850- 51; on Coast Survey, Apr., 1851, to Dec. 1, 1856, being engaged in the Primary Triangulation of the Coast of :Maine, >lnd Surveys of Appomattox and James Rivers, Va, 1851-53,- and Survey of (FrRs'r LIEUT., CORPS OF ENGINEERS, DEC. 18, 1854) Pncific Coast, including Astronomical, Tid,.I, and Magnetic Observations, 1853··56. RESIGNED, DEC. 1, 1856. Civil History.-Professor of Mathematics, University of Michigan, 1856-57. Degree of A. M., conferred by University of Rochester, N. Y., 1856. Scien tific Secretary of the Superintendent of the U. S. Coast Suney, 1857- 61, and on Hydrographic SUrYey of a part of Narl'llgull!;ctt Bay, R.. r., 1861. Served during the Rebellion of the Seceding States, 1861- 65: in chArge of the Engineer Agency, at New York city, for supplying m,\terial8 for fortifi cations, &0., and eonstruct.ing [md shipping engineer equipage for armie~ in the field, 1861-65; and Superintending Engineer of the COllstl'llction of FOit at Willett's Point, N. -

Bref Historique De L'exploitation De La Mine De Saizerais

b Faisabilité d'une approche spatialisée Y. Lucas (LAEGO - ENSMN) L. Vaute (BRGM) Septembre 2001 Ecole des Mines Parc Saurupt 54042 Nancy Cedex tél:0383584281 Ifax: 03835797- email : [email protected] http://www.mines.u-nancy.fr/gisos Rapport BRGMIRP-51132-FR Modélisation hydrodynamique de l'ancienne mine de fer de Saizerais Faisabilité d'une approche spatialisée Y.Lucas et L. Vaute Etude réalisée dans le cadre du projet de recherche du BRGM 01-RIS-R07 Septembre 2001 BRGMIRP-51132-FR - - BRGML.E"rnlM. A" -0, DIU m." Modélisation hydrodynamique de l'ancienne mine de fer de Saizerais Mots clés : Mines de fer, Hydrogéologie, Modélisation, Galeries, Modèle spatialisé En bibliographie, ce rapport sera cité de la façon suivante : Y. Lucas, L.Vaute (2001) - Modélisation hydrodynamique de l'ancienne mine de fer de Saizerais. Faisabilité d'une approche spatialisée. Rapport- - BRGM/RP-51132-FR 69 pages, 36 figures, 5 tableaux,-11 annexes. O BRGM. 2001. Ce document ne peut être reuroduit en totalité ou en pariie sans l'autorisation expresse du BRGM. 2 Rapport BRGM/RP-51132-FR Modélisation hydrodynamique de l'ancienne mine de fer de Saizerais Synthèse L'arrêt des pompages d'exhaure, consécutifs à l'abandon des mines du bassin ferrifère lorrain depuis une dizaine d'années, a provoqué l'ennoyage d'une grande partie du réseau de galeries minières, amenant une modification du régime hydrologique et une détérioration de la qualité de l'eau souterraine, essentiellement en raison de l'augmentation de la minéralisation (sulfate, sodium, magnésium, strontium, fer, manganèse, bore et nickel). Afin de mieux comprendre et de pouvoir prévoir l'évolution de ces phénomènes, différentes méthodes de modélisation ont été développées. -

Meurthe-Et-Moselle

2015 MISE À JOUR PARTIELLE 2016 TLAS DÉPARTEMENTAL MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE 3 ’Atlas départemental est un outil d’information et de connaissance de la Meurthe-et-Moselle. Il s’adresse aux élus, aux agents du conseil départemental ainsi qu’aux partenaires dont certains ont contribué à son ÉDITO élaboration. L’Atlas est en effet le fruit d’un travail collaboratif, mené à partir Ldes données statistiques et des analyses fournies par les services et partenaires du Département. Mise à jour de 75 indicateurs en 2016 L’Atlas départemental fait l’objet cette année d’une mise à jour de 75 indicateurs sur les 250 que contenait la version 2015. L’actualisation concerne les principaux indicateurs associés aux politiques publiques de la collectivité, les plus dynamiques et ceux dont l’évolution par rapport à 2015 présente un réel intérêt. La sélection couvre un grand nombre de thématiques : démographie, niveau de vie, emploi, économie solidaire et insertion, services à la population, solidarité, aménagement… La prochaine version complète de l’Atlas, avec l’ensemble des indicateurs, paraîtra en 2017. Comme pour les versions précédentes, les indicateurs 2016 sont illustrés par des graphiques, courbes et tableaux déclinés à l’échelle des six territoires d’action du Département ainsi que par des cartes permettant de compléter et de visualiser les éléments statistiques présentés. Un texte synthétique identifie les spécificités territoriales marquantes et permet la comparaison avec les tendances observées au sein de l’ancienne région Lorraine, de la nouvelle région Grand Est et de la France métropolitaine. Des définitions permettent en outre d’éclairer le lecteur sur les notions-clés pour chacune des thématiques. -

RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS Édition N° 6 Du 22 Janvier 2021

RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS Édition n° 6 du 22 janvier 2021 Le acte dans "eur int#$ralit# %euvent &tre !onsult# à "a pr#(ecture ou aupr) de ervi!e !on!ern# * Le recuei" %eut au si &tre !onsu"t# + • ur "e ite Internet de ervi!e de ",État en Meurt-e.et.Mo e""e + ///*0eurthe.et.0o e""e*$ouv*(r RECUEIL N° 6 22 janvier 2021 S O M M A I R E ARRÊTÉS, DÉCISIONS, CIRCULAIRES........................................................................................................................................................................................................2 PREFECTURE DE MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE................................................................................................................................................................................................2 CABINET DU PRÉFET.....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 DIRECTION DES SÉCURITÉS................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 Bureau de la représentation de l'Etat.....................................................................................................................................................................................................2 Arrêté préfectoral N° 2021 – 01 accordant la -

Meurthe Et Moselle Meuse

Genre NomPrénom Titre Maires Adresse CP Ville MEURTHE ET MOSELLE Monsieur TARDY Yvan Maire de ANDILLY Mairie-Place de l'Eglise 54200 ANDILLY Monsieur COLLET Thierry Maire de ANSAUVILLE Mairie-2 rue de l'Eglise 54470 ANSAUVILLE Monsieur CAILLOUX René Maire de ARNAVILLE Mairie-98 Grande Rue 54530 ARNAVILLE Madame ROCH Marie-Line Maire de BAYONVILLE SUR MAD Mairie-1 rue de Biard 54890 BAYONVILLE SUR MAD Monsieur CIOLLI Christophe Maire de BEAUMONT Mairie-8 Grande rue 54470 BEAUMONT Monsieur LAURENT Serge Maire de BELLEVILLE Mairie-Rue de la Mairie 54940 BELLEVILLE Monsieur BUVET Daniel Maire de BERNECOURT Mairie-12 Grande Rue 54470 BERNECOURT Monsieur LIOUVILLE Gérald Maire de BOUCQ Mairie-1 place du Souvenir 54200 BOUCQ Monsieur RENOUARD Gérard Maire de BOUILLONVILLE Mairie-9 rue Sur l'Eau 54470 BOUILLONVILLE Monsieur MANET Claude Maire de BRULEY Mairie- 36 rue Victor Hugo 54200 BRULEY Monsieur MANGIN Michel Maire de BRUVILLE Mairie-1Bis rue de l'Ecole 54800 BRUVILLE Madame ROSELEUR Lise Maire de CHAMBLEY BUSSIERES Mairie-12 rue de l'Eglise 54890 CHAMBLEY BUSSIERES Monsieur LARA Lionel Maire de CHAREY Mairie-10 rue Edmond Henry 54470 CHAREY Monsieur ARGAST Michel Maire de DAMPVITOUX 19 rue de la Mairie 54470 DAMPVITOUX Monsieur POIRSON Henri Maire de DIEULOUARD Mairie-8 rue Saint Laurent-BP 13 54380 DIEULOUARD Monsieur SEGAULT Jean-François Maire de DOMEVRE-EN-HAYE Mairie-2 place de l'Eglise 54385 DOMEVRE EN HAYE Monsieur PETIT Denis Maire de DOMMARTIN LA CHAUSSEE Mairie-3 rue de l'Eglise 54470 DOMMARTIN LA CHAUSSEE Monsieur SILLAIRE Roger -

DEPARTEMENT DE MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE 1Ère Circonscription

DEPARTEMENT DE MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE 1ère circonscription CUSTINES BRIN-SUR-SEILLE BOUXIERES-AUX-CHENES BRIN-SUR-SEILLE MONCEL-SUR-SEILLE BOUXIERES-AUX-CHENES MAZERULLES BOUXIERES-AUX-DAMES BOUXIERES-AUX-DAMES AMANCE AMANCE MAZERULLES LLAY--SAIINT--CHRIISTOPHE EULMONT SORNEVILLE EULMONT LAITRE-SOUS-AMANCE SORNEVILLE LAITRE-SOUS-AMANCE CHAMPENOUX DOMMARTIN- CHAMPENOUX DOMMSOAURST-IANM-SAONUCSE-AMANCE AGINCOURT LANEUVELOTTE AGINCOURT MALZEVILLE LANEUVELOTTE DOMMARTEMONT SEICHAMPS SEICHAMPS VELAINE-SOUS-AMANCE ESSEY-LES-NANCY ESSEY-LES-NANCY SAINT-MAX PULNOY NANCY-2 PULNOY SAULXURES-LES-NANCY NANCY SAULXURES-LES-NANCY NANCY-3 Légende Couleur : Canton Entre Seille et Meurthe Grand Couronné Saint-Max Nancy-3 Nancy-2 SICOM 54 06/12/2016 DEPARTEMENT DE MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE 2ème circonscription NANCY-1 LAXOU JARVILLE- LA-MALGRANGE VILLERS-LES-NANCY VANDOEUVRE-LES-NANCY HEILLECOURT HOUDEMONT LUDRES Légende Couleur : Canton Laxou Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy Jarville-la-Malgrange Nancy-1 SICOM 54 06/12/2016 DEPARTEMENT DE MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE 3ème circonscription MONT-SAINT-MARTIN VILLE-HOUDLEMONT MONT-SAINT-MARTIN GORCY LONGLAVILLE SAULNES GORCY LONGLAVILLE VILLE-HOUDLEMONT SAINT-PANCRE SAULNES COSNES-ET-ROMAIN HERSERANGE COSNES-ET-ROMAIN LONGW Y LONGW Y SAINT-PANCRE HERSERANGE TELLANCOURT LEXY MEXY VILLERS-LA-CHEVRE MEXY ALLONDRELLE-LA-MALMAISON TELLANCOURT LEXY ALLONDRELLE-LA-MALMAISON VILLERS-LA-CHEVRE HAUCOURT-MOULAINE FRESNOIS-LA-MONTAGNE REHON HUSSIGNY-GODBRANGE EPIEZ-SUR-CHIERS FRESNOIS-LA-MONTAGNE HAUCOURT HUSSIGNY-GODBRANGE -MOULAINE EPIEZ-SUR-CHIERS