Croydon 1937: Portrait of Death and Disposal in an Interwar Suburb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casualties ASSOCIATED with The

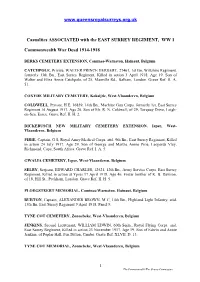

www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk Casualties ASSOCIATED with the EAST SURREY REGIMENT, WW 1 Commonwealth War Dead 1914-1918 BERKS CEMETERY EXTENSION, Comines-Warneton, Hainaut, Belgium CATCHPOLE , Private, WALTER PRINCE HERBERT, 27461, 1st Bn, Wiltshire Regiment. formerly 13th Bn., East Surrey Regiment, Killed in action 3 April 1918. Age 19. Son of Walter and Eliza Annie Catchpole, of 25, Manville Rd., Balham, London. Grave Ref. II. A. 51. COXYDE MILITARY CEMETERY, Koksijde, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium COLDWELL , Private, H E, 16839, 14th Bn., Machine Gun Corps. formerly 1st, East Surrey Regiment 14 August 1917. Age 20. Son of Mr. R. N. Coldwell, of 29, Torquay Drive, Leigh- on-Sea, Essex. Grave Ref. II. H. 2. DICKEBUSCH NEW MILITARY CEMETERY EXTENSION, Ieper, West- Vlaanderen, Belgium PIRIE , Captain, G S, Royal Army Medical Corps. attd. 9th Bn., East Surrey Regiment, Killed in action 24 July 1917. Age 29. Son of George and Martha Annie Pirie, Leopards Vley, Richmond, Cape, South Africa. Grave Ref. I. A. 5. GWALIA CEMETERY, Ieper, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium SELBY , Serjeant, EDWARD CHARLES, 12521, 12th Bn., Army Service Corps. East Surrey Regiment, Killed in action at Ypres 17 April 1918. Age 46. Foster brother of K. B. Dawson, of 18, Hill St., Peckham, London. Grave Ref. II. H. 5. PLOEGSTEERT MEMORIAL, Comines-Warneton, Hainaut, Belgium BURTON , Captain, ALEXANDER BROWN, M C, 14th Bn., Highland Light Infantry. attd. 13th Bn. East Surrey Regiment 9 April 1918. Panel 9. TYNE COT CEMETERY, Zonnebeke, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium JENKINS , Second Lieutenant, WILLIAM EDWIN, 60th Sqdn., Royal Flying Corps. and, East Surrey Regiment, Killed in action 23 November 1917. -

Green Flag Award Winners 2019 England East Midlands 125 Green Flag Award Winners

Green Flag Award Winners 2019 England East Midlands 125 Green Flag Award winners Park Title Heritage Managing Organisation Belper Cemetery Amber Valley Borough Council Belper Parks Amber Valley Borough Council Belper River Gardens Amber Valley Borough Council Crays Hill Recreation Ground Amber Valley Borough Council Crossley Park Amber Valley Borough Council Heanor Memorial Park Amber Valley Borough Council Pennytown Ponds Local Nature Reserve Amber Valley Borough Council Riddings Park Amber Valley Borough Council Ampthill Great Park Ampthill Town Council Rutland Water Anglian Water Services Ltd Brierley Forest Park Ashfield District Council Kingsway Park Ashfield District Council Lawn Pleasure Grounds Ashfield District Council Portland Park Ashfield District Council Selston Golf Course Ashfield District Council Titchfield Park Hucknall Ashfield District Council Kings Park Bassetlaw District Council The Canch (Memorial Gardens) Bassetlaw District Council A Place To Grow Blaby District Council Glen Parva and Glen Hills Local Nature Reserves Blaby District Council Bramcote Hills Park Broxtowe Borough Council Colliers Wood Broxtowe Borough Council Chesterfield Canal (Kiveton Park to West Stockwith) Canal & River Trust Erewash Canal Canal & River Trust Queen’s Park Charnwood Borough Council Chesterfield Crematorium Chesterfield Borough Council Eastwood Park Chesterfield Borough Council Holmebrook Valley Park Chesterfield Borough Council Poolsbrook Country Park Chesterfield Borough Council Queen’s Park Chesterfield Borough Council Boultham -

London in Bloom Results 2015 the London in Bloom Borough of The

London in Bloom Results 2015 The London in Bloom Borough of the Year Award 2015 Islington Gardeners Large City London Borough of Brent Silver Gilt London Borough of Hillingdon Silver Gilt London Borough of Ealing Gold London Borough of Havering Gold & Category Winner City Group A London Borough of Haringey Silver London Borough of Merton Silver London Borough of Sutton Silver Gilt Westminster in Bloom Gold & Category Winner City Group B Royal Borough of Greenwich Silver Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames Silver London Borough of Tower Hamlets Gold Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Gold Islington Gardeners Gold & Category Winner Town City of London Gold London Village Kyle Bourne Village Gardens, Camden Silver Barnes Community Association, Barnes Silver Gilt Hale Village, Haringey Silver Gilt Twickenham Village, Richmond upon Thames Silver Gilt Walthamstow Village in Bloom, Waltham Forest Gold & Category Winner Town Centre under 1 sq. km. Elm Park Town Centre, Havering Silver Canary Wharf, Tower Hamlets Gold & Category Winner Business Improvement District Croydon Town Centre BID, Croydon Bronze The Northbank BID, Westminster Bronze Kingstonfirst Bid, Kingston upon Thames Silver Gilt The London Riverside BID, Havering Silver Gilt Waterloo Quarter BID, Lambeth Silver Gilt London Bridge in Bloom, Southwark Silver Gilt & Category Winner Urban Community Charlton Triangle Homes, Greenwich Silver Gilt Bankside – Bankside Open Spaces Trust, Better Bankside/Southwark Silver Gilt & Category Winner Common of the Year (Sponsored by MPGA) Tylers -

Price List – Valid for All New Funerals Arranged from 6 July 2020 Onwards

Standard Funeral Service - £2,670 (or £2,765 including embalming) Professional Fee ............................................................................................................................................................ £1,050 • Taking all instructions and making the necessary arrangements for the funeral • Obtaining and preparing the necessary statutory documents • Liaising with cemetery/crematorium authorities • Liaising with hospitals, doctors, HM Coroner, clergy and other third parties • Providing advice on all aspects of the funeral arrangements Care of the Deceased ....................................................................................................................................................... £610 • Provision of private mortuary facilities prior to the funeral • Care of the deceased prior to the funeral • Provision of a standard white gown or dressing in clothes provided • Bereavement and aftercare assistance Vehicles and Funeral Staff ............................................................................................................................................ £1,010 • Closed hearse / private ambulance from place of death to our chapels (within a 10-mile radius of our premises) • Provision of a hearse and chauffeur on the day of the funeral • The provision of all necessary staff on the day of the funeral, including Funeral Conductor and four bearers • Provision of a limousine seating six people and chauffeur on the day of the funeral The Standard Funeral Service does not include -

Calico Printing Works, Wimbledon ("Merton Bridge")

Calico Printing Works, Wimbledon ("Merton Bridge") These works were situated on the west bank of the Wandle, about 100 yards downstream from where the present Byegrove Road crosses the river, where the "Merton Mills" were located. They were often described as being at or near Merton Bridge. On 20/21 July 1693 Samuel Crispe sold to William Knight, a potter of St. Botolph's, some land at Wimbledon which he had inherited from his father Ellis Crispe. This included the site of the calico printing works, which was at that time meadow land [1]. This was on the north side of adjoining land which Knight had purchased three years previously. The terms of the conveyance allowed Knight to build a mill on the river, and presumably he did so. However, the earliest reference found to a calico printer on the site was a notice of a commission of bankrupt issued against John Tozer, "of Martin's Bridge, Callico-printer", published in January 1719/20 [2]. Nothing has been discovered about the subsequent occupancy of the site until 24 December 1753, when William Walker of Wimbledon, calico printer, insured his dwelling house and nearby buildings including printing shop, calender house, copper house, colour house and drying room, and the utensils and goods therein, with the Royal Exchange insurance company [3]. The register entry of this policy refers to an earlier one taken out by Walker. The register containing the record of this has not been preserved, but judging from the policy number, it was probably issued in December 1750. William Walker was certainly living in Wimbledon at that time; his daughter Mary was baptised in the parish church on 26 August of that year. -

Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE

Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE From the Database of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE. From the Database of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Austria KLAGENFURT WAR CEMETERY Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 DIXON, Lance Corporal, RUBY EDITH, W/242531. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 4th October 1945. Age 22. Daughter of James and Edith Annie Dixon, of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. 6. A. 6. TOLMIE, Subaltern, CATHERINE, W/338420. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 14th November 1947. Age 32. Daughter of Alexander and Mary Tolmie, of Drumnadrochit, Inverness-shire. 8. C. 10. Belgium BRUGGE GENERAL CEMETERY - Brugge, West-Vlaanderen Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 MATHER, Lance Serjeant, DORIS, W/39228. Auxiliary Territorial Service attd. Royal Corps of Sig- nals. 24th August 1945. Age 23. Daughter of George L. and Edith Mather, of Hull. Plot 63. Row 5. Grave 1 3. BRUSSELS TOWN CEMETERY - Evere, Vlaams-Brabant Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 EASTON, Private, ELIZABETH PEARSON, W/49689. 1st Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Ser- vice. 25th December 1944. Age 22. X. 27. 19. MORGAN, Private, ELSIE, W/264085. 2nd Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 30th Au- gust 1945. Age 26. Daughter of Alfred Henry and Jane Midgley Morgan, of Newcastle-on-Tyne. X. 32. 14. SMITH, Private, BEATRICE MARY, W/225214. 'E' Coy., 1st Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 14th November 1944. Age 25. X. 26. 12. GENT CITY CEMETERY - Gent, Oost-Vlaanderen Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 FELLOWS, Private, DORIS MARY, W/76624. Auxiliary Territorial Service attd. 137 H.A.A. Regt. Royal Artillery. 23rd May 1945. Age 21. -

Henry Morgan – Purley Newsagent – Purley Pioneer

HENRY MORGAN – PURLEY NEWSAGENT – PURLEY PIONEER Olive Himsley(néeMorgan) talks to Jean Hain HENRY MORGAN – PURLEY NEWSAGENT – PURLEY PIONEER Olive Himsley(néeMorgan) talks to Jean Hain Cover: The Railway Hotel and High Street, Purley, in the 1900s.Henry Morgan'sshop towards the right. Postcard courtesy of Roger Packham. Published by The BourneSociety 2006 Copyright © 2006 The BourneSociety Henry Morgan, Chairman of Coulsdon & Purley Urban District Council 1925 Olive Himsley(néeMorgan) talks to Jean Hain HENRY MORGAN – PURLEY NEWSAGENT – PURLEYPIONEER Dedicated to the memory of Henry and AliceMorgan INTRODUCTION Olive Himsley, aged 91, is the youngest child of Henry and Alice Morganand these are some of Olive's memories of her father, her family and Purley. Henry Morganloved Purleyand he truly was a pioneer of the town. As well as owning Morgan's, the. newsagents which traded in the High Street for 83 years, he was also one of the first Councillors, later becoming Chairman of Coulsdonand PurleyUrban District Council, a President of PurleyRotary Club, a founder member of PurleyChamber of Commerce, a Justice of the Peace, Chairman of the Governors of two schools, a founder, member and Deacon of PurleyCongregational Church, a founder of Croydon Newsagents Association and a President of the National Federation of Retail Newsagents. Jean Hain December 2005 Page 1 Page 2 'MEADOW HURST' My father was Henry Thomas Morgan who owned the newsagents, stationers, sports goods and toy shop in the High Street, Purley. Father and my mother, Alice, were born in 1879. They met at the school in the High Street which much later became Christ Church School. -

Amery Mills, Merton

Amery Mills, Merton The site of these mills was on the final part of the curved course of the Wandle where it turns to run eastwards alongside Merton High Street, and about 100 yards west of Merton Bridge. Just to the south-east was the site of Merton Priory, usually called Merton Abbey. The priory was established in about 1117 by Gilbert Norman, and he arranged for an existing mill thereabouts to be resited [1]. This was probably one of the two mills at Merton included in the Domesday survey. The next reference to the premises found was on 4 November 1534, when two mills on the site, called Amery Mills, were leased by the incumbent prior to William Moraunt for the term of 27 years [1]. Following the surrender of the priory property to Henry VIII in about 1540, the mills became separated from those estates. In 1558 John Pennon was granted a 27-year lease of the mills, but remained there until about 1600. Edward Ferrars acquired the property on 19 May 1609, and it later passed to Richard Burrell, who sold the mills to Sir Francis Clerke. Sir Francis also acquired the priory estates, and thus the mills became once more part of those estates [2]. On 19 June 1624 he conveyed all his estates at Merton to Rowland Wilson, a London vintner. Wilson died in 1654, and by his will proved on 1 June 1654 he bequeathed the properties to his wife Mary [3]. They subsequently passed to her grandson Ellis Crispe, who in 1668 sold them to Thomas Pepys [2]. -

History Nugget January 2020 Timelines 1 Local Authorities

History Nugget for January 2020: Timelines No. 1 Local Authorities The Public Health Acts of 1873 and 1875 saw the creation of Sanitary Authorities for urban and rural districts. The Croydon Rural Sanitary District consisted of nine civil parishes surrounding the County Borough of Croydon that included Merton, Mitcham and Morden. The Local Government Act of 1894 abolished the sanitary districts, replacing them with urban and rural districts. In addition, it gave parishes the power to elect members to a parish council, and so the Mitcham Parish Council was formed, and remained part of the Croydon Rural District. Wimbledon, which had been an urban district from 1894, became a municipal borough in 1905. Merton Parish became an urban district in 1907, and in 1913 it absorbed Morden parish to become the Merton & Morden Urban District. In 1914 the Surrey County Council ordered the abolition of the Croydon rural district, and Mitcham parish became an urban district in 1915. Mitcham became a municipal borough in 1934. In 1965, under the London Government Act of 1963, the municipal borough of Mitcham was abolished, and its area combined with that of the Municipal Borough of Wimbledon and the Merton & Morden Urban District to form the present-day London Borough of Merton. Mitcham Cricket Green Community & Heritage General enquiries: [email protected] Web site: www.mitchamcricketgreen.org.uk Twitter: @MitchamCrktGrn Registered Office c/o MVSC, Vestry Hall, 336/338 London Road, Mitcham Surrey, CR4 3UD The Chairman of the Parish Council, Mr A. Mizen, reflected on the twenty years of its existence in a statement, recorded in the minutes of the last meeting of the Mitcham Parish Council on Wednesday 24th March 1915. -

To: Croydon Council Website Access Croydon & Town Hall

LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDON To: Croydon Council website Access Croydon & Town Hall Reception STATEMENT OF EXECUTIVE DECISIONS MADE BY THE CABINET MEMBER FOR HOMES REGENERATION AND PLANNING ON 8 FEBRUARY 2018 This statement is produced in accordance with Regulation 13 of the Local Authorities (Executive Arrangements) Meetings and Access to Information) (England) Regulations 2012. The following apply to the decisions listed below: Reasons for these decisions: are contained in the attached Part A report Other options considered and rejected: are contained in the attached Part A report Details of conflicts of Interest declared by the Cabinet Member: none Note of dispensation granted by the head of paid service in relation to a declared conflict of interest by that Member: none The Leader of the Council has delegated to the Cabinet Member the power to make the executive decision set out below: CABINET MEMBER’S DECISION REFERENCE NO. 0418HRP Decision title: Recommendation to Council to Adopt the Croydon Local Plan 2018 Having carefully read and considered the Part A report, including the requirements of the Council’s public sector equality duty in relation to the issues detailed in the body of the reports, the Deputy Leader (Statutory) and Cabinet Member for Homes Regeneration and Planning has RESOLVED under delegated authority (0418LR) the Deputy Leader (Statutory) and Cabinet Member for Homes, Regeneration and Planning to agree that the Croydon Local Plan 2018 be presented to Council with a recommendation to adopt it in accordance with s23(5) -

Landscape Character Assessment of the Wandle Valley London Landscape Character Assessment of the Wandle Valley London

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT OF THE WANDLE VALLEY LONDON LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT OF THE WANDLE VALLEY LONDON FUNDED BY NATURAL ENGLAND ON BEHALF OF THE WANDLE VALLEY PARTNERS: DECEMBER 2012 David Hares Landscape Architecture 4 Northgate Chichester PO19 1BA www.hareslandscape.co.uk 1 Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to the numerous people and organisations that have assisted with the preparation of this landscape character assessment. Particular thanks are due to the members of our 2008 steering group, Peter Massini and Adam Elwell at Natural England, as well as Angela Gorman at Groundwork London. We are grateful for the loan of material from the Environment Agency which has been supplied by Richard Copas and Tanya Houston. John Philips of Sutton Borough Council has kindly assisted with the history of the Upper Wandle, and supplied copies of historic illustrations from the Honeywood museum collection which we acknowledge with thanks. We must also give particular thanks to Jane Wilson and Claire Newillwho have guided us regarding the update of the assessment in 2012. This study included a workshop session, and we are very grateful to the representatives who gave up their time to attend the workshops and make helpful comments on character descriptions. We have endeavoured to faithfully include relevant suggestions and information, but apologise if we have failed to include all suggestions. Mapping and GIS work were undertaken by Paul Day, Matt Powell and colleagues at South Coast GIS, whose assistance we gratefully acknowledge. Whilst we acknowledge the assistance of other people and organisations, this report represents the views of the consultants alone. -

Addresses of Funeral Services in the London Area Containing 1. Registrars of Death by Borough 2 2. Mosques with Funeral Serv

Addresses of Funeral Services in the London Area containing 1. Registrars of Death by Borough 2 2. Mosques with Funeral Services 8 3. Muslim Funeral Directors 16 4. Cemetery List by Borough 19 Published by Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd www.taha.co.uk 1. LONDON REGISTER OFFICES It is important to telephone the offices first as some town halls operate on an appointment only basis. Inner London boroughs City of London This service is provided by Islington Council City of Westminster Westminster Council House Marylebone Road, Westminster London, NW1 5PT 020 7641 1161/62/63 Camden Camden Register Office Camden Town Hall, Judd Street London, WC1H 9JE 020 7974 1900 Greenwich Greenwich Register office Town Hall, Wellington Street London, SE18 6PW 020 8854 8888 ext. 5015 Hackney Hackney Register Office 2 Town Hall, Mare Street London, E8 1EA 020 8356 3365 Hammersmith & Fulham Hammersmith & Fulham Register Office Fulham Town Hall, Harewood Road London, SW6 1ET 020 8753 2140 Islington Islington Register Office (and London City) Islington Town Hall, Upper Street London, N1 2UD 020 7527 6347/50/51 Kensington & Chelsea The Register Office Chelsea Old Town Hall, Kings Road London, SW3 5EE 020 7361 4100 Lambeth Lambeth Register Office, Brixton Hill, Lambeth London, SW2 1RW 020 7926 9420 Lewisham Lewisham Register Office 368 Lewisham High Street London, SE13 6LQ 020 8690 2128 3 Southwark Southwark Register Office 34 Peckham Road, Southwark London, SE5 8QA 020 7525 7651/56 Tower Hamlets Tower Hamlets Register Office Bromley Public Hall, Bow Road London, E3 3AA