Topography and Domestic Architecture to the Middle of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download a Leaflet with a Description of the Walk and A

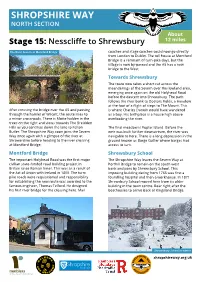

SHROPSHIRE WAY NORTH SECTION About Stage 15: Nesscliffe to Shrewsbury 12 miles The River Severn at Montford Bridge coaches and stage coaches could now go directly from London to Dublin. The toll house at Montford Bridge is a remnant of turn-pike days, but the village is now by-passed and the A5 has a new bridge to the West. Towards Shrewsbury The route now takes a short cut across the meanderings of the Severn over this lowland area, emerging once again on the old Holyhead Road before the descent into Shrewsbury. The path follows the river bank to Doctors Fields, a meadow at the foot of a flight of steps to The Mount. This After crossing the bridge over the A5 and passing is where Charles Darwin would have wandered through the hamlet of Wilcott, the route rises to as a boy. His birthplace is a house high above a minor crossroads. There is Motte hidden in the overlooking the river. trees on the right and views towards The Breidden Hills as you continue down the lane to Felton The final meadow is Poplar Island. Before the Butler. The Shropshire Way soon joins the Severn weir was built further downstream, the river was Way once again with a glimpse of the river at navigable to here. There is a long depression in the Shrawardine before heading to the river crossing ground known as Barge Gutter where barges had at Montford Bridge. access to turn. Montford Bridge Shrewsbury School The important Holyhead Road was the first major The Shropshire Way leaves the Severn Way at civilian state-funded road building project in Porthill Bridge to remain on the south-west Britain since Roman times. -

Report Into Infant Cremations at the Emstrey Crematorium Shrewsbury

Report into Infant Cremations at the Emstrey Crematorium Shrewsbury May 2015 Foreword Last November, Shropshire Council asked me to lead an inquiry into the way in which infant cremations have been carried out at the Emstrey Crematorium, in Shrewsbury. I began work in December 2014, and have been ably supported throughout by John Doyle, an independent research assistant. There can surely be no more painful experience than losing one’s infant child. Bereaved families have carefully and vividly explained to me how their sense of emptiness after losing their child felt all the more desolate for having had no ashes returned to them after the cremation. They feel strongly that to have retained a tangible memory of their lost child would have helped them through their grieving. This inquiry has established that the cremation equipment and techniques that were employed at the Emstrey Crematorium between 1996 and 2012 resulted in there being no ashes from the cremation of children of less than a year old that could be returned to funeral directors and families. This practice seems to have been accepted locally as the norm. The inquiry has also established that, using appropriate equipment and cremation techniques, it is normally possible to preserve ashes from infant cremations. The records show that ashes have been returned to funeral directors in all cases of infant cremations conducted at Emstrey since new equipment was installed, and different cremation techniques adopted, from January 2013. I hope that this report explains to families, councillors, staff and others, the circumstances that resulted in no ashes being returned to bereaved families between 1996 and 2012. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

NEW YORK TIMES BUILDING, 41 Park Row (Aka 39-43 Park Row and 147-151 Nassau Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 16, 1999, Designation List 303 LP-2031 (FORMER) NEW YORK TIMES BUILDING, 41 Park Row (aka 39-43 Park Row and 147-151 Nassau Street), Manhattan. Built 1888-89; George B. Post, architect; enlarged 1903-05, Robert Maynicke, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 101 , Lot 2. On December 15, 1998, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the (former) New York Times Bu ilding and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 3). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Three witnesses, representing the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Municipal Art Society, and the Historic Districts Council , spoke in favor of the designation. The hearing was re-opened on February 23 , 1999 for additional testimony from the owner, Pace University. Two representatives of Pace spoke, indicating that the university was not opposed to designation and looked forward to working with the Commission staff in regard to future plans for the building. The Commission has also received letters from Dr. Sarah Bradford Landau and Robert A.M. Stern in support of designation. This item had previously been heard for designation as an individual Landmark in 1966 (LP-0550) and in 1980 as part of the proposed Civic Center Hi storic District (LP-1125). Summary This sixteen-story office building, constructed as the home of the New York Times , is one of the last survivors of Newspaper Row, the center of newspaper publishing in New York City from the 1830s to the 1920s. -

Gloucestershire County Bridge Association

Gloucestershire County Bridge Association Minutes of the Annual General Meeting held at Cheltenham Bridge Club on Sunday 21st May 2017 at 1.30pm. The President (Jim Simons) was in the Chair and 40 other members attended 1 There was one apology for absence received 2 The minutes of the AGM held on June 5th 2016 were approved nem con with no corrections 3 President’s Report I’d like to start by expressing my thanks, and I hope yours, to all the people who have worked for the association over the year. Volunteer-run organisations don’t run without the volunteers! Starting with the officers, David Simons as secretary, Val Constable as Treasurer, Paul Denning as Chief Tournament Director, and Anne Swannell as catering officer have done most of the heavy lifting. We have recently co-opted Patrick Shields as Vice-President and he has been doing work on strategy, and we shall be hearing from him shortly. Peter Waggett has taken it upon himself to collect the money most Mondays – he says he quite likes money! As usual the Cheltenham Congress and the Green Point event in Ross-on-Wye were great successes attracting players from far afield as well as the local. We owe a great debt of gratitude to those who worked so hard to run them. For the congress, that is David Simons, Val Constable, Anne Swannell, Ro Kaye, John Skjonnemand and Paul Clarke. For the Green Point Event, it is pretty much just Alan Wearmouth, and the Herefordshire people. Looking at results outside the county, way back almost a year ago in June 2016, Wendy and Joe Angseesing and Ian and Val Constable won the Midland Counties Challenge Bowl ahead of teams from Worcestershire, Warwickshire Staffordshire and Derbyshire. -

£550 Per Calendar Month 21 Heritage Green, Forden

TO LET £550 Per calendar month 21 Heritage Green, Forden, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 8LH A newly constructed 2 bedroom semi-detached house with parking and rear enclosed garden, on a well located residential development, situated a short distance from the centre of the popular semi-rural village of Forden. hallsgb.com 01938 555 552 TO LET 1 Reception 2 Bedroom/s 2 Bath/Shower Room/s Room/s ■ Brand New Build SERVICES ■ Oil Fired Central Heating Mains electricity, drainage & water are ■ Open Plan Living understood to be connected. Oil fired central ■ 2 Double Bedrooms heating. ■ Private Parking None of these services have been tested by ■ Village Location Halls. Powys County Council Local Authority VIEWINGS ACCOMMODATION Strictly by appointment only with the selling Accommodation briefly comprises open plan agents Halls, Old Coach Chambers, 1 Church kitchen living space, downstairs w/c and under Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7LH. Tel No: stairs cupboard. Upstairs 2 double bedrooms 01938 555552 Email: [email protected] with dual aspect windows and a family bathroom. SITUATION Forden is a popular residential village sat at TERMS the foot of the renowned Long Mountain. It has Rent: £550 per calendar month. Deposit: £630. a basic range of amenities including Church, Minimum 6 month tenancy. Public House, Garage, School and Community First months rent and deposit are payable in Centre. The development is situated only 5 advance. miles from Welshpool, 15 miles from Sorry; No Pets. Newtown, 20 miles from Oswestry and 25 miles from Shrewsbury, all of which have a more comprehensive range of amenities of all kinds. -

Statute Law Revision Bill 2007 ————————

———————— AN BILLE UM ATHCHO´ IRIU´ AN DLI´ REACHTU´ IL 2007 STATUTE LAW REVISION BILL 2007 ———————— Mar a tionscnaı´odh As initiated ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 [No. 5 of 2007] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas., 1. c. 3 General Pier and Harbour Act 1861 Amendment Act 1862 25 & 26 Vict., c. -

Alcoholics Anonymous Shropshire Area Amended October 2016 AA National 0800 9177 650

Alcoholics Anonymous Shropshire Area Amended October 2016 AA National 0800 9177 650 AA Group Sunday Time Open Meetings Postcode Salvation Army, Lion Street, Oakengates Big Book Study 7:30pm - 9:00pm all open TF2 6AQ Chapter House, 12 Belmont, Shrewsbury (entrance to rear) 7:30pm - 9:00pm SY1 1TE Senior Citizens Hall, Curriors Lane, Shifnal Just for Today 11:30am – 1:00pm all open TF11 83J AA Group Monday Oxen Church Hall, Bicton Heath, Shrewsbury 7:30pm - 9:00pm SY3 5AG Broseley Room, Princess Royal Hospital, Telford 7:30pm - 9:00pm first Mon TF1 6TF St John’s Church Hall, High Town, Bridgnorth Big Book Study 7:30pm - 9:00pm all open WV16 4ER Quaker Meeting House, Oak Street, Oswestry 8.00pm – 9.30pm first Mon SY11 2ES St John’s Ambulance HQ, Smithfield Car Park, Lower Galdeford, Ludlow 12.30pm - 1.30pm all open SY8 1SA AA Group Tuesday St Nicholas Church, English Bridge, Shrewsbury Step Meeting 7:30pm - 9:00pm SY3 7BJ Jubilee House, High Street, Madeley 7:30pm - 9:00pm TF7 5AH Methodist Church, Broad St, Ludlow 8.00pm – 9.30pm all open SY8 1NH Oswestry Tuesday, Evangelical Church, Albert Road, Oswestry 8:00pm - 9:30pm SY11 1NH Portico House Tues, Portico House, 22 Vineyard Road, Wellington 11:30am – 1:00pm all closed TF1 1HB (Ring bell and when buzzer sounds push door to open. Ask at reception for AA meeting, sign in with, first name plus initial) AA Group Wednesday Salvation Army, Lion Street, Oakengates 7:30pm - 9:00pm first Wed TF2 6AQ The Redwoods Centre, Somerby Road, Bicton Heath, Shrewsbury 8:00pm - 9:30pm SY3 8DS The Catholic Presbytery, The Bridgend, Long Bridge St, Newtown (entrance to the rear) Study Group 7:00pm - 8:30pm SY16 2BJ Senior Citizens Hall, Curriors Lane, Shifnal Just for Today 7:45pm - 9:15pm all open TF11 8EQ St. -

From Maiden and Martyr to Abbess and Saint the Cult of Gwenfrewy at Gwytherin CYCS7010

Gwenfrewy the guiding star of Gwytherin: From maiden and martyr to abbess and saint The cult of Gwenfrewy at Gwytherin CYCS7010 Sally Hallmark 2015 MA Celtic Studies Dissertation/Thesis Department of Welsh University of Wales Trinity Saint David Supervisor: Professor Jane Cartwright 4 B lin a thrwm, heb law na throed, [A man exhausted, weighed down, without hand or A ddaw adreef ar ddeudroed; foot, Bwrw dyffon i’w hafon hi Will come home on his two feet. Bwrw naid ger ei bron, wedi; The man who throws his crutches in her river Byddair, help a ddyry hon, Will leap before her afterwards. Mud a rydd ymadroddion; To the deaf she gives help. Arwyddion Duw ar ddyn dwyn To the dumb she gives speech. Ef ai’r marw’n fyw er morwyn. So that the signs of God might be accomplished, A dead man would depart alive for a girl’s sake.] Stori Gwenfrewi A'i Ffynnon [The Story of St. Winefride and Her Well] Tudur Aled, translated by T.M. Charles-Edwards This blessed virgin lived out her miraculously restored life in this place, and no other. Here she died for the second time and here is buried, and even if my people have neglected her, being human and faulty, yet they always knew that she was here among them, and at a pinch they could rely on her, and for a Welsh saint I thinK that counts for much. A Morbid Taste for Bones Ellis Peters 5 Abstract As the foremost female saint of Wales, Gwenfrewy has inspired much devotion and many paeans to her martyrdom, and the gift of healing she was subsequently able to bestow. -

Egyptian Architecture

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE Character: simplicity, massiveness, monumentality Material: stone and brick System: columnar and trabaeted Comparative analysis: Plans- irregular and asymmetrical Wall- no windows (batter wall) Openings- doors are square headed Roof- flat roof Columns- interior only, 6d - bud & bell, palm, foliated, hatthor head, osiris, polygonal Mouldings- torus and gorge Principal buildings: Egyptian Tombs: Mastaba- stairway, halfshrunk, elaborate structure elements: offering chapel w/ stele (slab) serdab (statue chamber) sarcophagus Pyramid- square in plan, oriented in cardinal sides elements: offering chapel mortuary chapel elevated causeway (passageway)) valley building (embalmment) types: step (zoser) slope blunt (seneferu) Rock-cut- mountain side tombs elements: passages sepultural chamber Egyptian Temples: Cult temple- worship of the gods Mortuary Temple- to honor the pharos elements: pylon (entrance or gateway) hypaethral court (open to the sky court) hypostyle hall (pillard or columnar hall) sanctuary Minor temple- mammisi temple (carved along mountain) obelisk temple (monumental pillars, square in plan) Sphinx: (mythical monsters) Mastaba of Thi, Sakkara- Pyramid of Gizeh- Cheops, Chepren, Mykerinos Tombs of the Kings, Thebes The Great Temple of Arnak (greatest example of Egyptian temple) Great Sphinx at Gizeh (god horus) Egyptian Architects: Senusurets- built the earliest known obelisk at Heliopolis Amenemhat I- founded the great temple at Karnak Thothmes I- began the additions to the temple of Amnon Karnak Amenophis