Social Capital in Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera Outbreak Weekly AWD/Cholera Situation Report 10 – 17 November 2016

YEMEN: Cholera Outbreak Weekly AWD/Cholera Situation Report 10 – 17 November 2016 This official joint-report is based on information Yemen Cholera Taskforce, which is led by the Ministry of Health, WHO/Health Cluster, UNICEF/WASH Cluster and is supported by OCHA. Key Figures As of 17 November 2016, 90 Al Jawf Aflah Ash Shawm Khamir Kuhlan Ash Sharaf Abs Amran cases of cholera were confirmed Hajjah Al Miftah Hadramaut Ash Shahil Az Zuhr Arhab Nihm A ah Sharas in 29 districts with 8 cases of lluh ey ah Bani Qa'is HamdanBani Al Harith Marib deaths from cholera. Amanat Al AsimahBani Hushaysh Al Mahwit Ma'ain Sana'a Az Zaydiyah As Sabain n Khwlan As Salif a h n a S WHO/ MoPHP estimates that Bajil As Salif ra Al Marawi'ah Bu Al Mina Shabwah 7.6M people are at risk in 15 Al HaliAl Hudaydah Al Hawak Al MansuriyahRaymah Ad Durayhimi Dhamar governorates. iah aq l F h t A a ay y B r Y a a r h im S Al Bayda bid Za h s A total of 4,825 suspected cases A Hazm Al Udayn HubayshAl Makhadir Ibb Ash Sha'ir ZabidJabal Ra's s Ibb Ba'dan ra Qa'atabah Al Bayda City ay Hays Al Udayn uk are reported in 64 districts. JiblahAl Mashannah M Far Al Udayn Al Dhale'e M Dhi As SufalAs Sayyani a Ash Shu'ayb Al Khawkhah h a As Sabrah s Ad Dhale'e q u Al Hussein b H Al Khawkhah a Jahaf n l Abyan a A Cholera case fatality rate (CFR) h Al Azariq a h k u Mawza M TaizzJabal Habashy l A is 1.5 % Al Milah Al Wazi'iyah Lahj T u Al Hawtah Tur A b Incidence rate is 4 cases per l Bah a a h n Dar Sad Khur Maksar Al Madaribah Wa Al Arah Aden Al Mansura 10,000. -

Stand Alone End of Year Report Final

Shelter Cluster Yemen ShelterCluster.org 2019 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER CLUSTER End Year Report Shelter Cluster Yemen Foreword Yemeni people continue to show incredible aspirations and the local real estate market and resilience after ve years of conict, recurrent ood- environmental conditions: from rental subsidies ing, constant threats of famine and cholera, through cash in particular to prevent evictions extreme hardship to access basic services like threats to emergency shelter kits at the onset of a education or health and dwindling livelihoods displacement, or winterization upgrading of opportunities– and now, COVID-19. Nearly four shelters of those living in mountainous areas of million people have now been displaced through- Yemen or in sites prone to ooding. Both displaced out the country and have thus lost their home. and host communities contributed to the design Shelter is a vital survival mechanism for those who and building of shelters adapted to the Yemeni have been directly impacted by the conict and context, resorting to locally produced material and had their houses destroyed or have had to ee to oering a much-needed cash-for-work opportuni- protect their lives. Often overlooked, shelter inter- ties. As a result, more than 2.1 million people bene- ventions provide a safe space where families can tted from shelter and non-food items interven- pause and start rebuilding their lives – protected tions in 2019. from the elements and with the privacy they are This report provides an overview of 2019 key entitled to. Shelters are a rst step towards achievements through a series of maps and displaced families regaining their dignity and build- infographics disaggregated by types of interven- ing their self-reliance. -

Summary of the Evaluation I

Summary of the Evaluation I. Outline of the Project Project Title: Broadening Regional Initiative for Country: Yemen Developing Girls’ Education (BRIDGE) Program in Taiz Governorate Cooperation Scheme: Technology Cooperation Sector: Basic Education Project Basic Education Team I, Group I Total cost (as of the time of evaluation): 4.5 billion Division in (Basic Education), Human Japanese yen Charge: Development Department Implementing organization in Yemen: Taiz Governorate Education Office (R/D) 23 March 2005 Organization in Japan: JICA Cooperation Related Cooperation: School Construction in Taiz, Three years and five months Period Ibb and Sanaa (Grant Aid), Classroom renovation in (2005.6.22–2008.11.30) Taiz (Grassroots Grant Aid) 1-1 Background of the Project The Government of Yemen has considered that education is fundamental to its development. In 2003, the Ministry of Education (MOE) developed its Basic Education Development Strategy (BEDS) for 2003-2015, and has been carrying out the promotion of girls’ education as one of vital policies of education in Yemen. Along this line, the Government of Yemen and the Government of Japan agreed to implement the BRIDGE Project on 23 March 2005. The Project started in June 2005 and will be completed in the end of November 2008. 1-2 Project Overview (1) Overall Goal Girls’ access to basic education in Taiz Governorate is increased. (2) Project Purpose The effective model of regional educational administration based on community participating and school initiatives is developed for improving girls’ access to educational opportunities in the targeted districts in Taiz Governorate. (3) Outputs of the Project Output 1 Taiz Governorate’s capacity on regional educational administration is enhanced. -

Uninvestigated Laws of War Violations in Yemen's War with Huthi Rebels

Yemen HUMAN All Quiet on the Northern Front? RIGHTS Uninvestigated Laws of War Violations in Yemen’s War with Huthi Rebels WATCH All Quiet on the Northern Front? Uninvestigated Laws of War Violations in Yemen’s War with Huthi Rebels Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-607-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org March 2010 1-56432-607-1 All Quiet on the Northern Front? Uninvestigated Laws of War Violations in Yemen’s War with Huthi Rebels Map of Yemen’s Northern Governorates ..................................................................................... -

Form and Function of Complex Networks

F O R M A N D F U N C T I O N O F C O M P L E X N E T W O R K S P e t t e r H o l m e Department of Physics Umeå University Umeå 2004 Department of Physics Umeå University 901 87 Umeå, Sweden This online version differs from the printed version only in that the figures are in colour, the text is hyperlinked and that the Acknowledgement section is omitted. Copyright c 2004 Petter Holme ° ISBN 91-7305-629-4 Printed by Print & Media, Umeå 2004 Abstract etworks are all around us, all the time. From the biochemistry of our cells to the web of friendships across the planet. From the circuitry Nof modern electronics to chains of historical events. A network is the result of the forces that shaped it. Thus the principles of network formation can be, to some extent, deciphered from the network itself. All such informa- tion comprises the structure of the network. The study of network structure is the core of modern network science. This thesis centres around three as- pects of network structure: What kinds of network structures are there and how can they be measured? How can we build models for network formation that give the structure of networks in the real world? How does the network structure affect dynamical systems confined to the networks? These questions are discussed using a variety of statistical, analytical and modelling techniques developed by physicists, mathematicians, biologists, chemists, psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists. -

Public Displays of Connection

Public displays of connection J Donath and d boyd Participants in social network sites create self-descriptive profiles that include their links to other members, creating a visible network of connections — the ostensible purpose of these sites is to use this network to make friends, dates, and business connections. In this paper we explore the social implications of the public display of one’s social network. Why do people display their social connections in everyday life, and why do they do so in these networking sites? What do people learn about another’s identity through the signal of network display? How does this display facilitate connections, and how does it change the costs and benefits of making and brokering such connections compared to traditional means? The paper includes several design recommendations for future networking sites. 1. Introduction Since then, use of the Internet has greatly expanded and today ‘Orkut [1] is an on-line community that connects people it is much more likely that one’s friends and the people one through a network of trusted friends’ would like to befriend are present in cyberspace. People are accustomed to thinking of the on-line world as a social space. Today, networking sites are suddenly extremely popular. ‘Find the people you need through the people you trust’ — LinkedIn [2]. Social networks — our connections with other people — have many important functions. They are sources of emotional and ‘Access people you want to reach through people you financial support, and of information about jobs, other people, know and trust. Spoke Network helps you cultivate a and the world at large. -

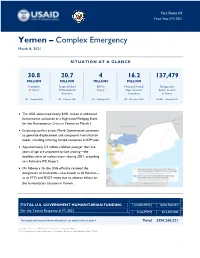

2021 03 08 USG Yemen Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2

Fact Sheet #2 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Yemen – Complex Emergency March 8, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 30.8 20.7 4 16.2 137,479 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Population People in Need IDPs in Projected Acutely Refugees and of Yemen of Humanitarian Yemen Food- Insecure Asylum Seekers Assistance Population in Yemen UN – February 2021 UN – February 2021 UN – February 2021 IPC – December 2020 UNHCR – February 2021 The USG announced nearly $191 million in additional humanitarian assistance at a High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen on March 1. Escalating conflict across Marib Governorate continues to generate displacement and compound humanitarian needs, including straining limited resources at IDP sites. Approximately 2.3 million children younger than five years of age are projected to face wasting—the deadliest form of malnutrition—during 2021, according to a February IPC Report. On February 16, the USG officially revoked the designation of Ansarallah—also known as Al Houthis— as an FTO and SDGT entity due to adverse effects on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1 $336,760,221 For the Yemen Response in FY 2021 2 State/PRM $13,500,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total $350,260,221 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA). 2 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM). 1 KEY DEVELOPMENTS USG Announces $191 Million at Humanitarian Pledging Conference The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland virtually hosted a High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen on March 1. -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNDERSTANDING THE HOUTHI CONFLICT IN NORTHERN YEMEN: A SOCIAL MOVEMENT APPROACH BY AndrewDumm Submitted to the Faculty of the School of International Service of American University in Partiai Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of the Arts m International Affairs Chair: Professor Carl LeVan Dean of the School of International Service CJOfD Date 2010 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNJVERSJTY liBRARY Cf:55() UMI Number: 1484559 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI ....----Dissertation Publishing.....___ UMI 1484559 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Pro uesr ---- ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml48106-1346 ©COPYRIGHT by AndrewDumm 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED To my parents UNDERSTANDING THE HOUTHI CONFLICT IN NORTHERN YEMEN: A SOCIAL MOVEMENT APPROACH BY AndrewDumm ABSTRACT Since 2004, the Yemeni government has been fighting a bloody civil war with local Zaydi Shia forces known as the Houthis in the country's north. Conventional explanations rooted in the recent history of the civil war fail to adequately account for the rise of the rebels and their fundamental grievances, however. A social movement approach, which can contextualize the Houthi rebellion within a historical evolution of Zaydi movements, is used here to · explain the transition of the Houthis from non-violent social movement to armed insurrectionary group. -

The Geoeconomics of Reconstruction in Yemen

The Geoeconomics of Reconstruction in Yemen Kristin Smith Diwan, Hussein Ibish, Peter Salisbury, Stephen A. Seche, Omar H. Rahman, Karen E. Young November 16, 2018 The Geoeconomics of Reconstruction in Yemen Kristin Smith Diwan, Hussein Ibish, Peter Salisbury, Stephen A. Seche, Omar H. Rahman, Karen E. Young Policy Paper #2 2018 The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (AGSIW), launched in 2015, is an independent, nonprofit institution dedicated to providing expert research and analysis of the social, economic, and political dimensions of the Gulf Arab states and how they impact domestic and foreign policy. AGSIW focuses on issues ranging from politics and security to economics, trade, and business; from social dynamics to civil society and culture. Through programs, publications, and scholarly exchanges the institute seeks to encourage thoughtful debate and inform the U.S. policy community regarding this critical geostrategic region. © 2018 Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. All rights reserved. AGSIW does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSIW, its staff, or its board of directors. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from AGSIW. Please direct inquiries to: [email protected] This publication can be downloaded at no cost at www.agsiw.org. Cover Photo Credit: AP Photo/Nariman El-Mofty About the UAE Security Forum For the third consecutive year, AGSIW will convene the UAE Security Forum, where U.S., UAE, and regional partners will gather to find creative solutions to some of the region’s most pressing challenges. -

Delineating and Calculating the Length of Yemen's Mainland

International Journal of Alternative Fuels and Energy Research Article 2021 │Volume 5│Issue 1│1-9 Open Access Delineating and Calculating the Length of Article Information Yemen's Mainland Shoreline Received: February 20, 2021 * Accepted: March 29, 2021 Hisham M. H. Nagi Published: April 30, 2021 Department Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Petroleum and Natural Resources, Sana'a Keywords University, Sana’a, Yemen. Shoreline, Coast of Yemen, Abstract: Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, The Republic of Yemen is one of the countries gifted with a long coastal line. The Arabian Sea, coastal zone is rich with biodiversity and a wide range of coastal ecosystems, which GIS. is vital to the livelihood of the coastal communities. Despite the fact that several Authors’ Contribution studies have described its coastal characteristics, there are still obvious variations in HMHN designed and performed the experiments. HMHN wrote and stating the actual length of its shoreline. In many reports and research studies, the revised the paper. coastline length of Yemen's mainland has been reported with different figures such How to cite as 1,906, 2,000, 2,100, 2,200 2,300, 2,350, and 2,520 km. This research paper aims Nagi, H.M.H., 2021. Delineating to substantiate the actual shoreline length of Yemen, in addition, to calculate the and Calculating the Length of length of each coastal governorate and district using GIS tools. This study showed Yemen's Mainland Shoreline. Int. J. Altern. Fuels. Energy., 5(1): 1-9. that the total length of Yemen's mainland shoreline is about 2,252 km, with approximately 770 km overlooks the Red Sea and 1,482 km of the southern *Correspondence Hisham M. -

June 2013 - February 2014

Yemen outbreak June 2013 - February 2014 Desert Locust Information Service FAO, Rome www.fao.org/ag/locusts Keith Cressman (Senior Locust Forecasting Officer) SAUDI ARABIA spring swarm invasion (June) summer breeding area Thamud YEMEN Sayun June 2013 Marib Sanaa swarms Ataq July 2013 groups April and May 2013 rainfall totals adults 25 50 100+ mm Aden hoppers source: IRI RFE JUN-JUL 2013 Several swarms that formed in the spring breeding areas of the interior of Saudi Arabia invaded Yemen in June. Subsequent breeding in the interior due to good rains in April-May led to an outbreak. As control operations were not possible because of insecurity and beekeepers, hopper and adult groups and small hopper bands and adult swarms formed. DLIS Thamud E M P T Y Q U A R T E R summer breeding area SEP Suq Abs Sayun winter Marib Sanaa W. H A D H R A M A U T breeding area Hodeidah Ataq Aug-Sep 2013 swarms SEP bands groups adults Aden breeding area winter hoppers AUG-SEP 2013 Breeding continued in the interior, giving rise to hopper bands and swarms by September. Survey and control operations were limited due to insecurity and beekeeping and only 5,000 ha could be treated. Large areas could not be accessed where bands and swarms were probably forming. Adults and adult groups moved to the winter breeding areas along the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden coasts where early first generation egg-laying and hatching caused small hopper groups and bands to DLIS form. Ground control operations commenced on 27 September.