James Maccullagh (1809‐47)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMES Maccullagh (1809-1847)

Hidden gems and Forgotten People ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE JAMES MacCULLAGH (1809-1847) James MacCullagh, the eldest of twelve children, was born in the townland of Landahussy in the parish of Upper Badoney, Co. Tyrone in 1809. He was to become one of Ireland and Europe's most significant mathematicians and physicists. He entered Trinity College, Dublin aged just 15 years and became a fellow in 1832. He was accepted as a member of the Royal Irish Academy in 1833 before attaining the position of Professor of Mathematics in 1834. He was an inspiring teacher who influenced a generation of students, some of whom were to make their own contributions to the subjects. He held the position of Chair of Mathematics from 1835 to 1843 and later Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy from 1843 to 1847. In 1838 James MacCullagh was awarded the Royal Irish Academy's Cunningham Medal for his work 'On the laws of crystalline reflexion'. In 1842, a year prior to his becoming a fellow of the Royal Society, London, he was awarded their Copley Medal for his work 'On surfaces of the second order'. He devoted much of the remainder of his life to the work of the Royal Irish Academy. James MacCullagh's interests went beyond mathematical physics. He played a key role in building up the Academy's collection of Irish antiquities, now housed in the National Museum of Ireland. Although not a wealthy man, he purchased the early 12th century Cross of Cong, using what was at that time, his life savings. In August 1847 he stood unsuccessfully as a parliamentary candidate for one of the Dublin University seats. -

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell JAMES CLERK MAXWELL Perspectives on his Life and Work Edited by raymond flood mark mccartney and andrew whitaker 3 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries c Oxford University Press 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2013942195 ISBN 978–0–19–966437–5 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

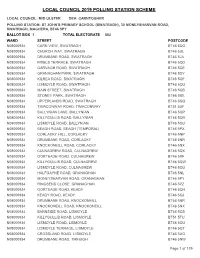

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER POLLING STATION: ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 882 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QG N08000934CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH BT46 5UL N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5JA N08000934FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH BT46 5QD N08000934GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QE N08000934GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5DY N08000934KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QF N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH BT46 5QB N08000934STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5BE N08000934UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QQ N08000934TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY BT51 5UF N08000934BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QP N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QR N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QU N08000934BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL) BT46 5PX N08000934CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY BT46 5NP N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NX N08000934CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QX N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5RF N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QW N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QU N08000934HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5NL N08000934MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PY N08000934RINGSEND CLOSE, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PZ N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QH N08000934KEADY ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QJ N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NX N08000934BARNSIDE ROAD, LISMOYLE -

The Cambridge Mathematical Journal and Its Descendants: the Linchpin of a Research Community in the Early and Mid-Victorian Age ✩

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematica 31 (2004) 455–497 www.elsevier.com/locate/hm The Cambridge Mathematical Journal and its descendants: the linchpin of a research community in the early and mid-Victorian Age ✩ Tony Crilly ∗ Middlesex University Business School, Hendon, London NW4 4BT, UK Received 29 October 2002; revised 12 November 2003; accepted 8 March 2004 Abstract The Cambridge Mathematical Journal and its successors, the Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal,and the Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, were a vital link in the establishment of a research ethos in British mathematics in the period 1837–1870. From the beginning, the tension between academic objectives and economic viability shaped the often precarious existence of this line of communication between practitioners. Utilizing archival material, this paper presents episodes in the setting up and maintenance of these journals during their formative years. 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Résumé Dans la période 1837–1870, le Cambridge Mathematical Journal et les revues qui lui ont succédé, le Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal et le Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, ont joué un rôle essentiel pour promouvoir une culture de recherche dans les mathématiques britanniques. Dès le début, la tension entre les objectifs intellectuels et la rentabilité économique marqua l’existence, souvent précaire, de ce moyen de communication entre professionnels. Sur la base de documents d’archives, cet article présente les épisodes importants dans la création et l’existence de ces revues. 2004 Elsevier Inc. -

Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents Trail to Discover His Family to America in 1819, Settling in Cincinnati

25 PLACES TO VISIT TO PLACES 25 MAP TRAIL POCKET including James Logan plaque, High Street, Lurgan FROM ULSTER ULSTER-SCOTS AND THE DECLARATION THE WAR OF 1 TO AMERICA 2 COLONIAL AMERICA 3 OF INDEPENDENCE 4 INDEPENDENCE ULSTER-SCOTS, The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England administration and defence of Colonial America. leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of SCOTCH-IRISH but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the AND SCOTS-IRISH Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World. development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775. -

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets Allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019 LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1/CN TOTAL ELECTORATE 880 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934 CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QG N08000934 CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5UL N08000934 DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5JA N08000934 FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QD N08000934 GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QE N08000934 GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5DY N08000934 KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QF N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QU N08000934 MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QB N08000934 STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5BE N08000934 UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QQ N08000934 TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY, KILREA BT51 5UF N08000934 BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QP N08000934 KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QR N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934 BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL), SWATRAGH BT46 5PX N08000934 CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NP N08000934 DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NR N08000934 KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NX N08000934 CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QX N08000934 GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5RF N08000934 KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QW N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934 HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN, SWATRAGH -

Tel. 028 8556 7723

Register early Completed application forms with payment (cheques made to reserve your chosen kit size. payable to Tyrone GAA), can be returned to your local primary school or posted to the address below: Garvaghey Centre, 230 Redergan Road, Dungannon, Co. Tyrone BT70 2EH. Tel. 028 8556 7723 “5 -13 year olds can attend Camps” Application forms available from www.tyronegaa.ie There will be a late registration fee of £5 per child for registrations received after the 27th June. Garvaghey Centre, Please tick camp attending 230 Redergan Road, Dungannon, Co. Tyrone BT70 2EH. Hurling/Camogie Football Multi-sport Tel. 028 8556 7723 Name/s ........................................................................................... Application forms available from ........................................................................................................ Age/s .............................................................................................. www.tyronegaa.ie 2014 School/s .......................................................................................... ........................................................................................................ Home Address ................................................................................ ........................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................ Name of Parent / Guardian............................................................ -

Foyle Heritage Audit NI Core Document

Table of Contents Executive Summary i 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of Study ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of the Audit ......................................................................................... 2 1.3 Project Team ......................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Study Area ............................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Divisions ................................................................................................................ 6 2 Audit Methodology .......................................................................................8 2.1 Identification of Sources ....................................................................................... 8 2.2 Pilot Study Area..................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Selection & Organisation of Data .......................................................................... 9 2.4 Asset Data Sheets ............................................................................................... 11 2.5 Consultation & Establishment of Significance .................................................... 11 2.6 Public Presentation ............................................................................................ -

Exploring the History & Heritage of Tyrone and the Sperrins

Exploring the History & Heritage of Tyrone and The Sperrins Millennium Sculpture Strabane Canal Artigarvan & Leckpatrick Moor Lough Lough Ash Plumbridge & The Glenelly Valley The Wilson Ancestral Home Sion Mills Castlederg Killeter Village Ardstraw Graveyard Stewart Castle Harry Avery’s Castle Patrick Street Graveyard, Strabane pPB-1 Heritage Trail Time stands still; time marches on. It’s everywhere you look. In our majestic mountains and rivers, our quiet forests and rolling fields, in our lively towns and scenic villages: history is here, alive and well. Some of that history is ancient and mysterious, its archaeology shaping our landscape, even the very tales we tell ourselves. But there are other, more recent histories too – of industry and innovation; of fascinating social change and of a vibrant, living culture. Get the full Local visitor App experience: information: Here then is the story of Tyrone and the Sperrins - Download it to your iphone The Alley Artsan and extraordinary journey through many worlds, from or android smartphone Conference Centre 1A Railway Sdistanttreet, Str pre-historyabane all the way to the present day. and discover even more Co. Tyrone, BT82 8EF about the History & Heritage It’s a magical, unforgettable experience. of Tyrone and The Sperrins. Email: [email protected] Web:www.discovertyroneandsperrins.com Tel: (028) 71Join38 4444 us and discover that as time marches on, time also stands still… p2-3 x the sites The sites are categorised 1 Millennium Sculpture 6 by heritage type as below 2 Strabane Canal 8 -

Pathfinderwest

#PathfinderWest 1 Introduction and Health Summit Programme #PathfinderWest Pathfinder: Taking an honest look at the delivery of “Our ambition is to give life to #PathfinderWest Health and Social Care Services for Fermanagh and Health and Wellbeing 2026: Health Summit TUESDAY 9 APRIL 2019 West Tyrone Delivering Together” in the Ardhowen Theatre, Enniskillen The Pathfinder Project has been large events taking place at venues With the PHA leading a recalibration Dear attendee, Having already listened to Session A: 9.30am – 12.30pm: undertaken by the Western Trust to across the region to present what of the population health needs over 2,200 people from all across A focus on the future design & planning of take a detailed focussed look at Health Pathfinder is about. analysis, the next phase in the Thank you for taking the time these communities, in addition Health & Social Care Services in Fermanagh and Social Care Services provision in process will involve seven appointed to join us at the Pathfinder West to our own staff, through and West Tyrone Fermanagh and West Tyrone. The second phase, which is viewed independent ‘Experts by Experience’ Health Summit. Pathfinder has a most comprehensive and by the Western Trust as integral in (Personal & Public Involvement) created a platform which brings thought provoking engagement 9.00am: Doors Open This includes looking at the achieving the overall aims of the joining a number of influential together people with expertise programme and having now Tea/Coffee, Scones on arrival population’s needs, -

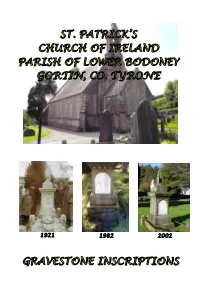

St. Patrick's C of I, Gortin

1921 1982 2002 ST. PATRICK’S PARISH CHURCH, LOWER BADONEY, GORTIN Thanks to Hazel Robinson for patiently helping to decipher and make the gravestone recordings on our many journeys to this peaceful graveyard of our ancestors. Colour photographs by Ann Robinson. Black & White photograph courtesy of Ann Dark. © 2017 A.K. ROBINSON 2 ST. PATRICK’S PARISH CHURCH, LOWER BADONEY, GORTIN ST. PATRICK’S CHURCH OF IRELAND, PARISH OF LOWER BODONEY (BADONEY), GORTIN, CO. TYRONE. The Parish of Badoney was originally a very large parish, stretching up the Glenelly Valley, with the oldest church site in the townland of Glenroan. This church is also called St. Patrick and this part of the parish eventually became Upper Badoney. The parish of Badoney was separated into two parts in 1730 and the first church of Lower Badoney, St. Patrick’s, was built in the village of Gortin. It was not until 1774 that the parish of Lower Badoney was constituted. The two parts were reunited again in 1924. In 1856 a new church was built in Lower Badoney at a cost of £1,921-15-00. This is the current church and is on a slightly different site to the older one. For many years parts of the old church, and the school, could be seen in the graveyard. In 1939 the graveyard was measured by J.C.M. Knox, Londonderry. In the 1980s all signs of the old church were removed when the graveyard was “tidied up.” From the First edition of the Ordnance Survey Maps (1832-1846) the position of the first church can be seen, along with the school. -

Client Derry City Council Project Glenelly Pilot Community Planning Project Division Consulting

Derry City Council Community Planning – Glenelly October 2011 Client Derry City Council Project Glenelly Pilot Community Planning Project Division Consulting October 2011 Derry City Council Community Planning – Glenelly October 2011 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 BACKGROUND TO COMMUNITY PLANNING.............................................................................................3 1.2 BIG LOTTERY – COMMUNITY PLANNING PILOT PROJECTS ..................................................................3 1.3 DERRY CITY COUNCIL AND STRABANE DISTRICT COUNCIL – COMMUNITY PLANNING PILOT........4 1.4 SCOPE & STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT.................................................................................................4 2 SOCIO ECONOMIC CONTEXT................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................5 2.2 OTHER PLANS ...........................................................................................................................................11 3 OVERVIEW OF CONSULTATION PROCESS.......................................................................................... 7 3.1 OUR APPROACH .........................................................................................................................................7