A Critical Analysis of Pakistan's Proposed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foundation University Medical College, Islamabad (BDS)

Foundation University Medical College, Islamabad (BDS) S# Candidate ID Name CNIC/NICOP/Passport Father Name Aggregate Category of Candidate 1 400119 Unaiza Ijaz 154023-376796-6 Ijaz Akhtar 92.66761364 Foreign Applicant 2 400218 Amal Fatima 362016-247810-6 Mohammad Saleem 92.29545455 Foreign Applicant 3 400266 Ayesha Khadim Hussain 323038-212415-6 Khadim Hussain 92.1875 Foreign Applicant 4 400114 Umar Fakhar 611012-326296-9 Nawaid Fakhar 90.6875 Foreign Applicant 5 302200 Parisa Saif Khan 61101-6413852-0 Saif Ullah Khan 90.47727273 Local Applicant 6 400148 Ayesha Bashir 373022-885861-0 Mirza Bashir Ahmed 89.78125 Foreign Applicant 7 303109 Sidra Batool 32203-4465194-8 Aman Ullah Khan 89.65909091 Local Applicant 8 300959 Linta Masroor 61101-6613020-4 Masroor Ahmad 89.56818182 Local Applicant 9 307998 Ujala Zaib 32102-7800856-0 Khalil Ur Rehman Buzdar 89.5 Local Applicant 10 301894 Alizay Ali 37301-8963956-8 Fawad Ali 89.38636364 Local Applicant 11 306454 Bakhtawar Mohsin Jami 42501-9843019-0 Mohsin Jami 89.20454545 Local Applicant 12 400237 Saad Sajjad Mughal AS9990403 Muhammad Sajjad Mughal 89.05113636 Foreign Applicant 13 400216 Hana Bilal 121016-527023-6 Muhammad Bilal Ahmad 88.94602273 Foreign Applicant 14 305067 Laiba Khalid 42201-1432628-6 Muhammad Khalid 88.93181818 Local Applicant 15 302632 Muhammad Akhtar 36203-8203731-9 Kareem Bukhsh 88.90909091 Local Applicant 16 301728 Ali Abbas Khan 33100-8906264-1 Shah Nawaz 88.90909091 Local Applicant 17 400059 Muhammad Sohaib Khan MJ4112853 Abdul Saeed Khan 88.86647727 Foreign Applicant -

Eighteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons International Seapower Symposium Events 10-2007 Eighteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings The U.S. Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/iss Recommended Citation Naval War College, The U.S., "Eighteenth International Seapower Symposium: Report of the Proceedings" (2007). International Seapower Symposium. 3. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/iss/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Events at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Seapower Symposium by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EIGHTEENTH INTERNATIONAL SEAPOWER SYMPOSIUM Report of the Proceedings ISS18.prn C:\Documents and Settings\john.lanzieri.ctr\Desktop\NavalWarCollege\5164_NWC_ISS-18\Ventura\ISS18.vp Friday, August 28, 2009 3:11:10 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen ISS18.prn C:\Documents and Settings\john.lanzieri.ctr\Desktop\NavalWarCollege\5164_NWC_ISS-18\Ventura\ISS18.vp Friday, August 28, 2009 3:11:12 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EIGHTEENTH INTERNATIONAL SEAPOWER SYMPOSIUM Report of the Proceedings 17–19 October 2007 Edited by John B. Hattendorf Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History Naval War College with John W. Kennedy NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT,RHODE ISLAND -

Pakistan Research Repository

Ph.D. Dissertation Pakistan’s Relations with China: A Study of Defence and Strategic Ties during Musharraf Era (1999-2008) A Thesis Submitted to Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of the Punjab In Candidancy for the Fulfillment of Doctor of Philosophy By Unsa Jamshed Pakistan Study Centre University of the Punjab, Lahore 2016 1 Dedication To My Honourable Supervisor, Prof. Dr. Massarrat Abid 2 Declaration I, Unsa Jamshed, hereby declare that this thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Pakistan-Studies, University of the Punjab, is wholly my personal research work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. This thesis has not been submitted concurrently to any other University for any other degree. __________________ Unsa Jamshed 3 Certificate by Research Supervisor This is to certify that the research work described in this thesis is the original work of the author and has been carried out under my supervision. I have personally gone through all the data reported in the manuscript and certify their authenticity. I further certify that the material included in this thesis has not been used in part of full in a manuscript already submitted or in the process of submission in partial/complete fulfillment of the award of any other degree from any other institution. I also certify that the thesis has been prepared under supervision according to the prescribed format and I endorse its evaluation for the award of Ph.D. degree through the official procedures of the University. ____________ Prof. Dr. Massarrat Adid, Director Pakistan Study Centre, University of the Punjab, Lahore. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

Tillerson Hails Kuwait's Role in Resolving Gulf Crisis

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 El Arabi nets a double INDEX as Duhail DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 4-10, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 ‘Uptick in infl ation’ REGION 11 BUSINESS 1-6, 17-20 see off likely on rising 23,277.00 8,172.18 51.84 ARAB WORLD 11 CLASSIFIED 7-16 +163.00 +28.07 +0.33 INTERNATIONAL 12-21 SPORTS 1-8 hydrocarbon prices Umm Salal +0.71% +0.34% +0.64% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10614 October 22, 2017 Safar 2, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Tillerson hails In brief Kuwait’s role QATAR | New premises Doha Municipality to relocate to old airport in resolving arrivals terminal Doha Municipality announced through a tweet that its off ices will be relocated to the old arrivals terminal at Doha International Airport (old NHRC Chairman Dr Ali bin Smaikh al-Marri speaking at the opening of the Arabic calligraphy exhibition on ‘Human Rights in Gulf crisis airport) at Ras Abu-Abboud area Islamic Culture’ in Madrid yesterday. from Al Sadd area, with eff ect from O US Secretary of State trip to the region in July. October 24. The phone numbers arrives in Saudi Arabia on Before his arrival at Riyadh’s King are 44347777 and 44347506, Salman air base yesterday, Tillerson in- hotline 184, fax 44320709, e-mail: visit to region dicated there had been little progress in [email protected] and O US top diplomat also to the mediation eff orts. “I do not have a website www.mme.gov.qa Siege violates all charters of visit Qatar lot of expectations for it being resolved anytime soon,” he said in an interview ARAB WORLD | Unrest with fi nancial news agency Bloomberg. -

Annual Report 2018-19.Pdf

REGIONAL AGRICULTRAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CENTRE (RAEDC), VEHARI ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 Dr. GHULAM ABBAS MUSHTAQ ALI FAHAD IHSAN, SAEED AHMAD Seed Farm Road RAEDC Vehari E-mail:[email protected] Web: https://raedc-agripunjab.punjab.gov.pk Ph: 067-3361690, 9201197, Fax: 067-3364428 1 INTRODUCTION Agriculture sector is an integral part of the economy of Pakistan. It is also a strategic priority of other developing countries for balancing export deficits and ensuring food security. To enhance and boost up agricultural production challenges of human resource development and technology transfer play a preeminent role in achievement of objective. Technology transfer mean a „system under which various inter-related components of technology namely “hardware” (materials such as a variety), “software” (technique, know-how, information), “human ware” (human ability), “orgaware” (organizational, management aspects) and the final product (including marketing) are rendered accessible to the end users‟. The pace of technology transfer can only be matched if the farming community is trained/ educated at the same speed. To institutionalize this activity, RAEDC was incepted in 1991. Regional Agricultural Economic Development Centre (RAEDC), Vehari has been organizing courses, which result in capacity building of the officers of the department as well which enhance the capabilities and skills of farmers, unemployed youth, women and labour class particularly related with agriculture. The process involves need assessment of the target populations, demand of the community, unfelt needs of new concepts and technologies. Teaching methods, course contents and training material is very carefully selected with reference to target audience. Teaching methods used in training courses generally involve lecture, field visit, hands-on training, group discussions, brain storming sessions and case studies etc. -

Uprising Commander, His Wife Shot Dead

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:XI Issue No:103 Price: Afs.20 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes THURSDAY . NOVEMBER 09. 2017 -Aqrab 18, 1396 HS AT News Report AT News Report KABUL: At least 39 militants were killed and 19 others were KABUL: President Ashraf Ghani, wounded in different crackdowns and the Vice President of the within past 24 hours. United States, Mike Pence had a In a statement, ministry of telephonic conversation on defense said that Afghan National Tuesday evening, in which both Army with the cooperation of the were killed. Residents said that a The US military has rejected US airstrike targeted a gathering of any civilian casualties during their sides discussed key issues, Afghan National Police and including topics of mutual and National Directorate of Security civilians on the weekend in the air raid. “United States Forces- unsafe district of Char Dara, killing Afghanistan (USFOR-A) has regional interests, the Presidential conducted joint operations against Palace said in a statement. Government and people. insurgents in different areas of at least 10 and wounding scores investigated allegations of civilian President Ghani thanked the more. casualties in Kunduz province According to the statement, Nangarhar, Ghazni, Logar, the two sides exchanged views Government and people of the Kandahar, Zabul, Balkh, Jawzjan, “Credible reports that at least during the period of November 3 United States for assisting the 10 civilians killed in Kunduz and 4; no evidence of civilian over topics of mutual and regional Faryab, Kunduz, Baghlan, interests. -

SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN, ISLAMABAD FINAL CAUSE LIST 13 of 2018 from 26-Mar to 30-Mar-2018 for Fixation and Result of Cases, Please Visit

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN, ISLAMABAD FINAL CAUSE LIST 13 of 2018 From 26-Mar to 30-Mar-2018 For fixation and result of cases, please visit www.supremecourt.gov.pk The following cases are fixed for hearing before the Court at Islamabad during the week commencing 26-Mar-2018 at 09:00 AM or soon thereafter as may be convenient to the Court. (i) No application for adjournment through fax/email will be placed before the Court. If any counsel is unable to appear for any reason, the Advocate-on-Record will be required to argue the case. (ii) No adjournment on any ground will be granted. BENCH - I MR. JUSTICE MIAN SAQIB NISAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE UMAR ATA BANDIAL MR. JUSTICE IJAZ UL AHSAN Monday, 26-Mar-2018 1 C.A.1178/2008 Haji Baz Muhammad and another v. Noor Mr. Abdus Salim Ansari, AOR (Qta) (Specific Performance) Ali and another (Enrl#229) (D.B.) Mr. Kamran Murtaza, ASC (Qta) (Enrl#2333) Mr. Rizwan Ejaz, ASC (Enrl#4107) (Qta) R Ex-Parte Mr. Ahmed Nawaz Chaudhry, AOR (Enrl#243) Mr. Zulfikar Khalid Maluka, ASC (Ibd) (Enrl#2752) 2 C.A.182-P/2013 Muhammad Fateh Khan & others v. Land Mr. Tasleem Hussain, AOR (Pesh) (Land Acquisition) Acquisition Collector Swabi Scarp, (Enrl#187) (S.J.) WAPDA Mardan & others Muhammad Asif Khan, ASC Mir Adam Khan, AOR (Enrl#185) (Pesh) Mr. Mahmudul Islam, AOR (Lhr) (Enrl#177) Mr. Aurangzeb Mirza, ASC (Lhr) (Enrl#2706) and(2) C.A.194-P/2013 Nawabzada Mohammad Usman Khan v. Mr. Muhammad Ajmal Khan, AOR (Pesh) (Land Acquisition) Land Acquisition Collector Swabi Scarp, (Enrl#225) (S.J.) Mardan & others Mr. -

Players Handicap

Karachi Golf Club W.E.F 17,September 2021 LIST OF HANDICAP W E F 12 January 2021. EXACT Play. S.no Mno N a m e H / C H / C 1 26 MR.ASGHAR D. HABIB 11.1 11 2 29 MRS. MAJIDA MOHSIN HABIB 34.0 34 3 32 MRS. ZUBAIDA HYDER HABIB 16.0 16 4 37 MRS. NISHAT KHAN 18.1 18 5 39 MR.NISSAR DOSSA 23.0 23 6 63 MR. KHAWAJA SAEED HAI 19.8 20 7 65 DR. M. S. HABIB 18.0 18 8 75 MR.MURTAZA QASIM 10.1 10 9 93 MR. AMINALI CURRIMBHOY 8.4 8 10 94 MR.SANAULLAH QURESHI 20.2 20 11 95 MR. MAHBOOB G. RAWJEE 21.5 22 12 105 MR.MAHMUD AHMAD 13.1 13 13 113 MR.VAZIR H.QURESHI 19.2 19 14 117 MR. ABBAS D. HABIB 13.9 14 15 119 MR. MUSLIM R. HABIB 16.3 16 16 120 MRS. PERVEEN MOHAMMAD 18.3 18 17 126 MR.KHALID RAFI 17.3 17 18 133 MR.HAMEEDULLAH KHAN 16.0 16 19 139 MR.HUSSAIN S. HAROON 12.6 13 20 145 MR. ASLAM R. KHAN 8.9 9 21 156 MR.MOHAMMAD BASHEER 18.0 18 22 159 MR. ADIL AHMED 17.0 17 23 162 MR. RAFIQUE DAWOOD 20.0 20 24 166 MR.ZAHID BASHEER 19.0 19 25 169 MRS. NAHEED MIRZA 18.0 18 26 172 MR. MOHAMMAD NASEER 21.8 22 27 174 MR. SALIM ADAYA 18.2 18 28 180 CAPT.MAHFOOZ ALAM (PIA) 14.4 14 29 184 MRS. -

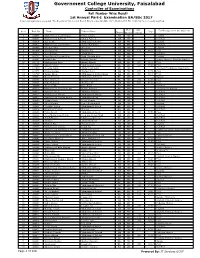

BA Bsc 1St Annual 2017 Part-I

Government College University, Faisalabad Controller of Examinations Roll Number Wise Result 1st Annual Part-I Examination BA/BSc 2017 Errors and omissions excepted. The Results of 1st Annual Part-I Examination BA/BSc 2017 (Held in JUL TO AUG-2017 ) are hereby notified. Max. Obt. Sr. # Roll No Name Father's Name %age Fail/Re-appear in the Subjects Degree Marks Marks 1 600579 Muhammad Asad Farooq Umar Farooq BA 400 English 2 600801 Muhammad Kamran Khalid Ameen BA 400 Full Fail 3 600814 Imran Ali Muhammad Anwar BA 400 English 4 600852 Muhammad Zubair Nasir Nasir Mahmood BA 400 Full Fail 5 600865 Mazhar Iqbal Suleman BA 400 English 6 602494 Sidra Kousar Roshan Din BA 400 179 44.75 Pass 7 603573 Aqeela Iram Abdul Haq BA 400 Full Fail 8 603703 Syed Bakar Hussain Shah Syed Hussain Shah BA 400 English 9 604487 Noor Sehar Ishtiaq Ahmad BSc. 400 Islamic Studies, Pakistan Studies 10 609796 Muhammad Sajid Bashir Ahmad BA 400 227 56.75 Pass 11 610865 Shoaib Aslam Muhammad Aslam BSc. 400 236 59.00 Pass 12 611840 Ayesha Aftab Abdul Latif Sabir BSc. 400 Applied Psychology, Geography 13 611874 Hadia Shafqat Shafqat Nazir BA 400 239 59.75 Pass 14 611980 Aisma Khan Muhammad Arshad Khan BA 400 203 50.75 Pass 15 800001 Kosar Parveen Muhammad Nawaz BSc. 400 Botany 16 800002 Saima Parveen Ghulam Hussain BSc. 400 252 63.00 Pass 17 800003 Saba Shahzadi Shahbaz Ali BA 400 198 49.50 Pass 18 800004 Ikram Ullah Israr Khan BA 400 Full Fail 19 800016 Muhammad Tabassum Ali Najam Perwaiz BSc. -

SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction)

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) Present : Mr. Justice Gulzar Ahmed Mr. Justice Sardar Tariq Masood Mr. Justice Faisal Arab Criminal Original Petition No.09 of 2018 {Suo Moto Contempt Proceedings initiated against Mr. Talal Chaudhry, State Minster on account of derogatory and contemptuous speeches/statements at public gathering in respect of this Hon’ble Court telecasted by different T.V. Channels} For the alleged : Mr. Kamran Murtaza, Sr. ASC Contemnor Syed Rifaqat Hussain Shah, AOR : For the State Ch. Aamir Rehman, Additional A.G. assisted by Barrister Asad Rahim Khan Date of hearing : 11.07.2018. O R D E R Gulzar Ahmed, J.:- On 01.02.2018, the Registrar of this Court had put up a note to the Hon’ble Chief Justice of Pakistan, the contents of the note are as follows:- “PUC are press clippings dated 13.09.2017, 14.01.2018, 20.01.2018 whereby statements were reported and transcripts of speeches at public gathering dated 24.01.2018 & 27.01.2018 telecast by different TV channels pertaining to Mr. Talal Chaudhry, State Minster. The statements are contemptuous and derogatory in respect of this Hon’ble Court with special reference to the decision of this Court dated 28.07.2017 passed in Constitution Petition 29/2016 etc. The words used constitute interference with and obstruction of the process of the Court as well as aimed at belittling the stature of the Apex Court. It is prima facie Contempt of Court in terms of Article 204 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan read with Section 3 of the Contempt of Court Ordinance, 2003. -

Fully Or Due to Naivety Ignored the Editors’ Body

LAST PAGE...P.8 SUNDAY C SEPTEMBER-2020 KASHMIR M 23 Y SRINAGAR TODAY :PARTLY CLOUDY Contact 27 : -0194-2502327 K FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS & YOUR COPY OF Maximum : 24°c SUNSET Today 06:20 PM Minmum : 10°c SUNRISE Humidity : 60% Tommrow 06:23 AM 09 Safar-ul-Muzaffar | 1442 Hijri | Vol: 23 | Issue: 213 | Pages: 08 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net twitter.com / kashmirobserver facebook.com/kashmirobserver Postal Regn: L/159/KO/SK/2014-2016 KO PhotoAbid Bhat C M Y K From Front page... Sunday | 27-09-2020 02 Quad Countries Deliberating On NCB Questions Bollywood Stars Common Approach On 5G Technology NEW DELHI: The US, India, Japan in touch with Japan for the de- and Australia are exploring to velopment of 5G technology, and evolve a common approach on 5G the issue was deliberated upon Deeepika, Shraddha, Sara In Drugs Case telecom technology, expanding extensively during the first for- their strategic cooperation under eign and defence ministerial dia- MUMBAI: The Narcotics Con- While Sara Ali Khan and Shrad- during questioning, sources said. all day at its Ballard Estate of- which did not materialise. the framework of Quadrilateral logue between the two strategic trol Bureau (NCB) on Saturday dhaKapoor were questioned at Padukone, who reached the fice. He was not seen leaving Chopra was briefly associated coalition or "Quad" which was partners in November last year. recorded statements of actors the NCB's zonal office at Ballard guest house around 9.50 am, left the office even late at night. with his banner as an assistant primarily focused on the Indo- "Noting the importance of digital DeepikaPadukone, ShraddhaKa- Estate, Padukone was questioned at 3.50 pm.