Sociability and Social Networking at the London Wardmote Inquest, C.1470-1540

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central London Plan Bishopsgate¬Corridor Scheme Summary

T T T T D S S S R Central London Plan EN H H H H H RE G G BETHNAL SCLATER S Bishopsgate¬corridor Scheme Summary I T H H ShoreditchShoreditch C Key T I HHighigh StreetStreet D E Bus gate – buses and cyclists only allowed R O B through during hours of operation B H R W R OR S I I Q Q SH C IP C S K Section of pavement widened K ST N T E Y O S T L R T A L R G A U Permitted turns for all vehicles DPR O L I N M O B L R N O F S C O E E S P ST O No vehicular accessNSN except buses P M I A FIF E M Email feedback to: T A E streetspacelondon@tfl.gov.uk G R S C Contains Ordnance Survey data LiverpoolLiverpool P I © Crown copyright 2020 A SStreettreet O L H E MoorgateM atete S ILL S T I ART E A B E T RY LANAN R GAG E R E O L M T OOO IVE * S/BS//B onlyoonlyy RP I OO D M L S O T D S LO * N/BN//B onlyoonlyy L B ND E S O ON S T RNR W N E A E LL X T WORM A WO S OD HOUH T GATEG CA T T M O R S R E O U E H S M NDN E G O T I T I A LE D H O D S S EL A G T D P M S B I A O P E T H R M V C . -

Broad Street Ward News

Broad Street:Broad Street 04/06/2013 12:58 Page 1 BROAD STREET BROADSHEET JUNE 2013 COMMUNICATING WITH THOSE WHO LIVE AND WORK IN THE CITY OF LONDON THE NEW CIVIC TEAM FOR BROAD STREET After a very hard fought election in March, when six candidates contested the three seats on the Court of Common Council, a new civic team now represents the Ward of Broad Street. John Bennett and John Scott were re-elected and are joined by Chris Hayward, all of whom have very strong links with the Ward through work and residence. In this edition we provide short profiles of the Common Councilmen and give their responsibilities for the coming term. John Bennett graduated in biochemistry from Christ Church, Oxford in 1967 and qualified as a Chartered Accountant with Arthur Andersen. He then spent the next 35 years in various roles in International Banking in London and Jersey with Citibank and Hill Samuel. During this time he developed a keen interest in Compliance and Regulation. He retired from Deutsche Bank in 2005 after serving as Director of Compliance and UK Money Laundering Reporting Officer. John is Deputy for the Ward and has represented the electors of Broad Street L to R: Chris Hayward CC, Deputy John Bennett, John Scott CC for the last eight years. He currently Ward Club. He is a Trustee of the Lord Bank, for over thirty years until he retired serves on the Port Health & Mayor’s 800th Anniversary Awards Trust, at the grand old age of 55. In his capacity Environmental Services Committee and established by the late Sir Christopher as Global Head of Public Sector Finance it the Community & Children’s Services Collett, late Alderman for the Ward, seemed logical to accept the suggestion Committee and in 2010 was elected to during his mayoral year, and a Trustee of of standing as an elected Member in 1998 serve on the Policy & Resources charities related to the Ward’s parish and ever since then he has represented Committee, the most senior committee church, St Margaret Lothbury. -

The Roman Wall Around Miles

Let’s walk! St Giles Cripplegate Use this map and the key to help you find your way around. Remember, you can pause the audio walk at any point to take a closer look at your surroundings, complete St Alphage one of the activities Gardens overleaf or to stop for a rest. Barbican Moorgate This walk will take about 23 minutes plus This circular walk starts Guildhall Yard. We’ll move through stops and covers 1.6km Barbican and St. Giles before looping back on ourselves and (1 mi). This walk is finishing where we began. On the way we’ll find out all about suitable for pushchairs life and work in Roman London– then called and wheelchairs. Londinium and how they kept the city safe. Remember to check the opening times and admission prices of any venues before starting Noble Street your walk. A list of Guildhall Yard them can be found on St. Paul’s the final page. Start and End Key Point of Interest Look out for Bex! As well as your audio guide, Rest points she’s also here to point out additional things and Restrooms give you fun challenges to complete as you walk. ^ Fold me along the lines and read me like a book! me like me along the lines and read ^ Fold Venues on and around the walk Fun Kids Family Walks: The City of London Remember to always check the opening times and admission prices of venues before starting your journey. The Roman Museum of London museumoflondon.org.uk Wall Barbican barbican.org.uk Guildhall guildhall.cityoflondon.gov.uk London’s Wall is one of the oldest structures in the City. -

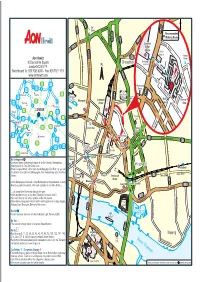

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4JQ

124 Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4JQ Charming self-contained Charming self-contained warehouse style office warehouse style office freehold with its own freehold with its own courtyard & rear garden courtyard & rear garden For Sale For Sale The Opportunity • Character Clerkenwell freehold, close to Smithfield, Farringdon and Barbican • Converted warehouse office building comprising a Net Internal Area of 4,981 sq ft (462.7 sq m) and a Gross Internal Area of 6,173 sq ft (573.5 sq m) • B1 officese u throughout • Exclusive private gated courtyard providing secure car parking for up to 3 cars • Secluded rear walled garden of approx. 1,500 sq ft • Attractive 1st floor terrace of approx. 600 sq ft • Potential to extend subject to securing the necessary consents • Sold with vacant possession on completion • Offers are invited for the freehold interest to include the front courtyard & rear garden Garden Lower Ground Floor Ground Floor Ground Floor Front Entrance The Location Connectivity The building sits in a cul-de-sac off Aldersgate Street with Charterhouse Square to the Barbican Station is within a minutes walk giving access to the Circle, west and Carthusian Street to the south. Clerkenwell Road is 300 metres to the north. Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan Lines. Farringdon Station is within 500 metres (7 minute walk) and is served by the same Tube lines, The immediate area benefits from the amenities of Smithfield Market and Clerkenwell Thameslink and Crossrail (from 2018). St Paul’s Station is a 10 minute walk Green, with a plethora of shops, bars and restaurants. The Barbican Centre, London to the south providing access to the Central Line. -

The London Gazette, Issue 11671, Page 4

Sii<> Certificate -will be allowed and confirmed as the said Act Andrew Robinson, formerly of Hutwo.;:h In the County of directs, unless Cause be sliewn to the contrary on or before the Durham, late of Alder'gate-street, London, Gentleman. 45th of' Jiine instant.- William Millar, formerly of Kinj-street St. Giles's in the 'He-reas the acting Commissioners in the Commission Fields, U:e of Cumberland-stie^t ne :r the Middlesex Hos= W ^of Bankrupt awarded againft Isaac Thornton; of Fleet- pital, both in Middlesex, Grocer and Cheesemonger. streets London, Wine and Brandy Merchant, Dealer' and Peter Hardcastle, lorn-.erly of White Hart-vard Catherine- Chapman, have certified to the Right Hon. Henry Earl Da- street in the Strand in the County of Middlesex, Jace of thurst, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, that said Isaac H irplane Tcwer-street, London, Cooper. Thornton- hath in all Things conformed according to the Direc James Stiel, formerly of Sa.isbury-court in the Pari/h of St» tions Of the several Acts of Parliament made concerning Bank Bride in the City of London, late of Mary Le Bone High-*> rupt* J This is to give Notice, that by virtue of an Act passed street in the County of Middlesex, Gentlrman. -in the Fifth Year of his late Majesty's Reign, his Certificate James Proud love, formerly of Giey Eagle-stree, late of •will be allowed and confirmed, as tbe said Act directs, unleis Wheeler-street in the Parish of Christ Church Spitalfields in Cause* be Ihewii to the contrary on or before the 25th of June the Counry of Middlesex, instant. -

Download Walking People at Your Service London

WALKING PEOPLE AT YOUR SERVICE IN THE CITY OF LONDON In association with WALKING ACCORDING TO A 2004 STUDY, WALKING IS GOOD COMMUTERS CAN EXPERIENCE FOR BUSINESS HAPPIER, MORE GREATER STRESS THAN FIGHTER PRODUCTIVE PILOTS GOING INTO BATTLE WORKFORCE We are Living Streets, the UK charity for everyday walking. For more than 85 years we’ve been a beacon for this simple act. In our early days our campaigning led to the UK’s first zebra crossings and speed limits. 94% SAID THAT Now our campaigns, projects and services deliver real ‘GREEN EXERCISE’ 109 change to overcome barriers to walking and LIKE WALKING JOURNEYS BETWEEN CENTRAL our groundbreaking initiatives encourage IMPROVED THEIR LONDON UNDERGROUND STATIONS MENTAL HEALTH ARE ACTUALLY QUICKER ON FOOT millions of people to walk. Walking is an integral part of all our lives and it can provide a simple, low cost solution to the PHYSICAL ACTIVITY PROGRAMMES increasing levels of long-term health conditions AT WORK HAVE BEEN FOUND TO caused by physical inactivity. HALF REDUCE ABSENTEEISM BY UP TO Proven to have positive effects on both mental and OF LONDON CAR JOURNEYS ARE JUST physical health, walking can help reduce absenteeism OVER 1 MILE, A 25 MINUTE WALK 20% and staff turnover and increase productivity levels. With more than 20 years’ experience of getting people walking, we know what works. We have a range of 10,000 services to help you deliver your workplace wellbeing 1 MILE RECOMMENDED WALKING activities which can be tailored to fit your needs. NUMBER OF DAILY 1 MILE BURNS Think of us as the friendly experts in your area who are STEPS UP TO 100 looking forward to helping your workplace become CALORIES happier, healthier and more productive. -

Broad Street Ward News

December 2016 Broad Street Guildhall School of Music & Drama – A centre of excellence for Performing Arts This is the final article for the Ward Since its founding in 1880, the School has performances by ensembles with which Newsletter this year featuring the stood as a vibrant showcase of the City the Guildhall School is associated, Committees of which the Members of London Corporation’s commitment namely Britten Sinfonia, the Academy of Common Council for the Ward to education and the arts. The School of Ancient Music and the BBC Singers. of Broad Street are Chairmen. The is run by the Principal, Professor Barry Ife Student performances are open to the Ward is probably unique in that all its CBE, supported by three Vice Principals public and tickets are available at very Common Councilmen are Chairmen (Music, Drama and Academic). The reasonable prices. of major committees of the City of School recently announced that Lynne London Corporation. The two previous Williams will become the next Principal, In 2014, following an application Newsletters have featured the submitted to the Higher Education Markets Committee chaired by John Funding Council for England (HEFCE), Scott CC and the Planning and the School was granted first degree Transportation Committee chaired awarding powers, enabling it to confer by Chris Hayward CC. its own first degrees rather than those of City University. John Bennett, Deputy for the Ward, is Chairman of the Board of Governors This summer, HEFCE conducted an of the Guildhall School of Music & institution-specific review which resulted Drama, owned by the City Corporation in the Guildhall School’s teaching being and part of the City’s Cultural Hub. -

Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places PDF 625 KB

Committee: Policy and Resources Committee Date: 2 October 2014 Subject: Review of Polling Districts and Polling Public Places Report of: Town Clerk For Decision Summary Each local authority is required to periodically conduct reviews into the polling districts and polling places used at UK Parliamentary elections within its area. The Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 introduced a change to the timing of these compulsory reviews, requiring a review to be started and completed by each local authority between 1 October 2013 and 31 January 2015 (inclusive), and in accordance with this timetable, the City of London has been conducting a review of its arrangements. In conducting the review, the City has been required to take certain steps set out in Schedule A1 of the Representation of the People Act (1983). Having following the statutory process, this report is to make recommendations to the Committee for the future arrangements for polling stations and polling places in the City to be used at UK Parliamentary elections. Recommendations The Committee is requested to agree that:- There should be no changes to the existing boundaries of polling district AL. Situated in the western part of the City, AL district contains the Bread Street, Castle Baynard, Cordwainer, Cheap, Farringdon Within, Farringdon Without, Queenhithe, and Vintry Wards. The polling place for AL polling district should continue to be St Bride Foundation, Bride Lane. There should be no changes to the existing boundaries of polling district CL. Situated on the Eastern side of the City, it covers Aldgate, Billingsgate, Bishopsgate, Bridge and Bridge Without, Broad Street, Candlewick, Cornhill, Dowgate, Langbourn, Lime Street, Portsoken, Tower and Walbrook Wards. -

IMAGINING EARLY MODERN LONDON Perceptions and Portrayals Ofthe Cipfrom Stow to Stvpe, R5g8-1720

IMAGINING EARLY MODERN LONDON Perceptions and Portrayals ofthe Cipfrom Stow to Stvpe, r5g8-1720 EDITED BY J. l? MERRITT CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB~PRU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 1001 I -421 I, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa 0Cambridge University Press 2001 The book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2001 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in I 1/12.5pt Baskerville System gb2 [CE] A catalogue recordfor thh book is avaihbkjFom the British Libray Library of Congr~sscataloguing in publication data Imagining early modern London: perceptions and portrayals of the city from Stow to Strype, 1598-1720 / edited by J. E Merritt. p. cm. Largely revised papers of a conference held at the Institute of Historical Research in July 1998. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN o 521 77346 6 I. London (England)- History - 17th century - Congresses. 2. Stow, John, 1525?-1605. Survey of London - Congresses. 3. London (England)- History - 18th century - Congresses. 4. London (England)- Historiography - Congresses. 5. Strype,John, 1643-1737 - Congresses. I. Merritt, J. ~~681.1432001 942.1'06-dc21 2001025~92 ISBN o 521 773466 hardback CHAPTER 4 C@, capital, and metropolis: the changing shape of seven teen th-century London Vanessa Harding Stow's original Survey and Strype's edition of it mark two date-points on the trajectory of early modern London's growth: neither the beginning nor the end, but sufficiently far apart for complex and dramatic changes to be visible in the city they describe. -

The Collaborative City

the londoncollaborative The Collaborative City Working together to shape London’s future March 2008 THE PROJECT The London Collaborative aims to increase the capacity of London’s public sector to respond to the key strategic challenges facing the capital. These include meeting the needs of a growing, increasingly diverse and transient population; extending prosperity while safe- guarding cohesion and wellbeing, and preparing for change driven by carbon reduction. For more information visit young- foundation.org/london Abbey Wood Abchurch Lane Abchurch Yard Acton Acton Green Adams Court Addington Addiscombe Addle Hill Addle Street Adelphi Wharf Albion Place Aldborough Hatch Alder- manbury Aldermanbury Square Alderman’s Walk Alders- brook Aldersgate Street Aldersgate Street Aldgate Aldgate Aldgate High Street Alexandra Palace Alexandra Park Allhal- lows and Stairs Allhallows Lane Alperton Amen Corner Amen CornerThe Amen Collaborative Court America Square City Amerley Anchor Wharf Angel Working Angel Court together Angel to Court shape Angel London’s Passage future Angel Street Arkley Arthur Street Artillery Ground Artillery Lane Artillery AperfieldLane Artillery Apothecary Passage Street Arundel Appold Stairs StreetArundel Ardleigh Street Ashen Green- tree CourtFORE WAustinORD Friars Austin Friars Passage4 Austin Friars Square 1 AveINTRO MariaDUctio LaneN Avery Hill Axe Inn Back6 Alley Back of Golden2 Square OVerVie WBalham Ball Court Bandonhill 10 Bank Bankend Wharf Bankside3 LONDON to BarbicanDAY Barking Barkingside12 Barley Mow Passage4 -

How to Find Hfw in London

HOW TO FIND HFW IN LONDON Friary Court 65 Crutched Friars London EC3N 2AE T +44 (0)20 7264 8000 F +44 (0)20 7264 8888 Mid p o dlesex St h Liverpool s i B Street Live rpoo l St New St Commercial S London Blomfield St Wall ve A Castle St Wor t mwoo d St t Harrow Pl S Middlesex St Throgmorton d Castle St Broa e Goulston St t t Aldgate S ld ga Gravel Ln East igh O B Hou l H Drum St ps ev o ape Bury Ct i n ch s dsdi te ish M St hi orton St B ar lph W Throgm k tc to s h o t Axe t B S Buckle St t St dle Bury Ct t lie S Duke's Braham S A Threadnee Ln Aldgate St Mary ch P L r l it u tle h Aldgate High S S c Mitre St o m e r ll St Leadenha Cree s Leadenha Jewry St e Cornhill ll St t V in Bank Mansell S e E tenter St te St N tenter St Lime St dga Al Leman S Ki t Fe W tenter St n S nch v ur A t g ch Lloyd' M W i i n Scarborough St lli s on St t London St vd hurch A orie Ha a c ve enter St m S e S T c Fenchurch s t Fenchurch St Fenchurch St V t Gra Street Station Portsoken St S i Crosswall n e Prescot S Cooper's Row Dunster Ct Crutched Friars t C dman's Yard res Goo ce Philpot Ln Heart St Road Ln Tower n Seething Ln t Monument Pepys St t Gateway Cable S M t Station Station (DLR) nt S Great ino Mi Mark Ln al Minsing Ln y r St t o u t-Hill T R th S M ow ri D r o are num er St Squ e A o m y s Tower ck en it t ia t in S l S Botolph Ln r Hill l t S il Idol Ln T l t St Mary-a l W il se wer H n St To a ing d M K ar L yw e DIRECTIONS BY PUBLIC TRANSPORT FROM GATWICK AIRPORT FROM CITY AIRPORT The nearest train station is Fenchurch Gatwick Express trains run to Victoria By taxi: There are usually black cabs Street.