The Lost Church of St Botolph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central London Plan Bishopsgate¬Corridor Scheme Summary

T T T T D S S S R Central London Plan EN H H H H H RE G G BETHNAL SCLATER S Bishopsgate¬corridor Scheme Summary I T H H ShoreditchShoreditch C Key T I HHighigh StreetStreet D E Bus gate – buses and cyclists only allowed R O B through during hours of operation B H R W R OR S I I Q Q SH C IP C S K Section of pavement widened K ST N T E Y O S T L R T A L R G A U Permitted turns for all vehicles DPR O L I N M O B L R N O F S C O E E S P ST O No vehicular accessNSN except buses P M I A FIF E M Email feedback to: T A E streetspacelondon@tfl.gov.uk G R S C Contains Ordnance Survey data LiverpoolLiverpool P I © Crown copyright 2020 A SStreettreet O L H E MoorgateM atete S ILL S T I ART E A B E T RY LANAN R GAG E R E O L M T OOO IVE * S/BS//B onlyoonlyy RP I OO D M L S O T D S LO * N/BN//B onlyoonlyy L B ND E S O ON S T RNR W N E A E LL X T WORM A WO S OD HOUH T GATEG CA T T M O R S R E O U E H S M NDN E G O T I T I A LE D H O D S S EL A G T D P M S B I A O P E T H R M V C . -

Committee(S) Dated: Planning and Transportation

Committee(s) Dated: Planning and Transportation 23rd June 2020 Subject: Public Delegated decisions of the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Report of: For Information Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Summary Pursuant to the instructions of your Committee, I attach for your information a list detailing development and advertisement applications determined by the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director or those so authorised under their delegated powers since my report to the last meeting. In the time since the last report to Planning & Transportation Committee Thirty-Nine (39) matters have been dealt with under delegated powers. Sixteen (16) relate to conditions of previously approved schemes. Six (6) relate to works to Listed Buildings. Two (2) applications for Non-Material Amendments, Three (3) applications for Advertisement Consent. One (1) Determination whether prior app required, Two (2) applications for works to trees in a conservation area, and Nine (9) full applications which, including Two (2) Change of Uses and 396sq.m of floorspace created. Any questions of detail arising from these reports can be sent to [email protected]. Details of Decisions Registered Address Proposal Applicant/ Decision & Plan Number & Agent name Date of Ward Decision 20/00292/LBC 60 Aldersgate (i) Replacement of single Mackay And Approved Street London glazed, steel framed Partners Aldersgate EC1A 4LA double height windows 04.06.2020 with double glazed aluminium framed windows (north and south facing elevations, first and second sub-podium levels) (ii) Retention of existing frames and replacement of single glazing with double glazing (north and south facing elevations, first sub-podium level) (iii) Retention of frames and replacement double glazed units (south and west facing elevations, second sub-podium level). -

Broad Street Ward News

Broad Street:Broad Street 04/06/2013 12:58 Page 1 BROAD STREET BROADSHEET JUNE 2013 COMMUNICATING WITH THOSE WHO LIVE AND WORK IN THE CITY OF LONDON THE NEW CIVIC TEAM FOR BROAD STREET After a very hard fought election in March, when six candidates contested the three seats on the Court of Common Council, a new civic team now represents the Ward of Broad Street. John Bennett and John Scott were re-elected and are joined by Chris Hayward, all of whom have very strong links with the Ward through work and residence. In this edition we provide short profiles of the Common Councilmen and give their responsibilities for the coming term. John Bennett graduated in biochemistry from Christ Church, Oxford in 1967 and qualified as a Chartered Accountant with Arthur Andersen. He then spent the next 35 years in various roles in International Banking in London and Jersey with Citibank and Hill Samuel. During this time he developed a keen interest in Compliance and Regulation. He retired from Deutsche Bank in 2005 after serving as Director of Compliance and UK Money Laundering Reporting Officer. John is Deputy for the Ward and has represented the electors of Broad Street L to R: Chris Hayward CC, Deputy John Bennett, John Scott CC for the last eight years. He currently Ward Club. He is a Trustee of the Lord Bank, for over thirty years until he retired serves on the Port Health & Mayor’s 800th Anniversary Awards Trust, at the grand old age of 55. In his capacity Environmental Services Committee and established by the late Sir Christopher as Global Head of Public Sector Finance it the Community & Children’s Services Collett, late Alderman for the Ward, seemed logical to accept the suggestion Committee and in 2010 was elected to during his mayoral year, and a Trustee of of standing as an elected Member in 1998 serve on the Policy & Resources charities related to the Ward’s parish and ever since then he has represented Committee, the most senior committee church, St Margaret Lothbury. -

The Custom House

THE CUSTOM HOUSE The London Custom House is a forgotten treasure, on a prime site on the Thames with glorious views of the river and Tower Bridge. The question now before the City Corporation is whether it should become a luxury hotel with limited public access or whether it should have a more public use, especially the magnificent 180 foot Long Room. The Custom House is zoned for office use and permission for a hotel requires a change of use which the City may be hesitant to give. Circumstances have changed since the Custom House was sold as part of a £370 million job lot of HMRC properties around the UK to an offshore company in Bermuda – a sale that caused considerable merriment among HM customs staff in view of the tax avoidance issues it raised. SAVE Britain’s Heritage has therefore worked with the architect John Burrell to show how this monumental public building, once thronged with people, can have a more public use again. SAVE invites public debate on the future of the Custom House. Re-connecting The City to the River Thames The Custom House is less than 200 metres from Leadenhall Market and the Lloyds Building and the Gherkin just beyond where high-rise buildings crowd out the sky. Who among the tens of thousands of City workers emerging from their offices in search of air and light make the short journey to the river? For decades it has been made virtually impossible by the traffic fumed canyon that is Lower Thames Street. Yet recently for several weeks we have seen a London free of traffic where people can move on foot or bike without being overwhelmed by noxious fumes. -

The Roman Wall Around Miles

Let’s walk! St Giles Cripplegate Use this map and the key to help you find your way around. Remember, you can pause the audio walk at any point to take a closer look at your surroundings, complete St Alphage one of the activities Gardens overleaf or to stop for a rest. Barbican Moorgate This walk will take about 23 minutes plus This circular walk starts Guildhall Yard. We’ll move through stops and covers 1.6km Barbican and St. Giles before looping back on ourselves and (1 mi). This walk is finishing where we began. On the way we’ll find out all about suitable for pushchairs life and work in Roman London– then called and wheelchairs. Londinium and how they kept the city safe. Remember to check the opening times and admission prices of any venues before starting Noble Street your walk. A list of Guildhall Yard them can be found on St. Paul’s the final page. Start and End Key Point of Interest Look out for Bex! As well as your audio guide, Rest points she’s also here to point out additional things and Restrooms give you fun challenges to complete as you walk. ^ Fold me along the lines and read me like a book! me like me along the lines and read ^ Fold Venues on and around the walk Fun Kids Family Walks: The City of London Remember to always check the opening times and admission prices of venues before starting your journey. The Roman Museum of London museumoflondon.org.uk Wall Barbican barbican.org.uk Guildhall guildhall.cityoflondon.gov.uk London’s Wall is one of the oldest structures in the City. -

Parking Information

Parking Information WHERE TO Visiting Old Billingsgate? PARK While there is no on-site parking at Old Billingsgate, there are ample parking opportunities at nearby car parks. The car parks nearest to the venue are detailed below: Tower Hill Corporation of London Car and Coach Park 50 Lower Thames Street (opposite Sugar Quay), EC3R 6DT 250m, 4 minute walk Monday - Friday 06:00 - 19:00 £3.50 per hour (for cars) Open 24 hrs, 7 days a week (including bank holidays) Saturday 06:00 - 13:30 £3.50 per hour (for cars) Number of Spaces: 110 cars / 16 coaches / 0 All other times £3.50 per visit commercial / 13 disabled (for cars) bays £10 per hour (for coaches) Free motorcycle and pedal cycle parking areas Overnight parking 17:00 - 09:00 capped at £25 (for coaches) London Vintry Thames Exchange – NCP Thames Exchange, Bell Wharf Lane, EC4R 3TB 0.4 miles, 8 minute walk 1 hour £3.20 Open 24 hrs, 7 days week 1 - 2 hours £6.40 (including bank holidays) 3 - 4 hours £12.80 Number of Spaces: 466 cars / 0 commercial / 5 - 6 hours £19.20 2 disabled bays 9 - 24 hours £32 Motorcycles £6.50 per day OLD BILLINGSGATE London Finsbury Square – NCP (Commercial Vehicle Parking) Finsbury Square, Finsbury, London, EC2A 1AD 1.1 miles, 22 minute walk 1 hour £5 Open 24 hrs, 7 days week 1 - 2 hours £10 (including bank holidays) 2 - 4 hours £18 Number of Spaces: 258 cars / 8 commercial / 2 4 - 24 hour £26 disabled bays Motorcycles £6 per day On-Street Bicycle Parking There are 40+ on-street cycle spaces within 5 minutes walk of Old Billingsgate. -

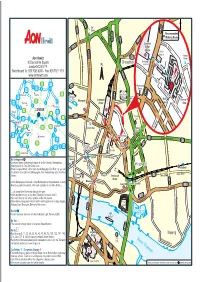

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

ST. PAUL's CATHEDRAL Ex. Par ALL HALLOWS, BERKYNCHIRCHE-BY

ST. JAMES AND ST. JOHN WITH ST. PETER, CLERKENWELL ST. LEONARD WITH ST. MICHAEL, SHOREDITCH TRINITY, HOLBORN AND ST. BARTHOLOMEW, GRAY'S INN ROAD ST. GILES, CRIPPLEGATE WITH ST. BARTHOLOMEW, MOOR LANE, ST. ALPHAGE, LONDON WALL AND ST. LUKE, OLD STREET WITH ST. MARY, CHARTERHOUSE AND ST. PAUL, CLERKE CHARTERHOUSE ex. par OBURN SQUARE CHRIST CHURCH WITH ALL SAINTS, SPITALF ST. BARTHOLOMEW-THE-GREAT, SMITHFIELD ST. BARTHOLOMEW THE LESS IN THE CITY OF LONDON ST. BOTOLPH WITHOUT BISHOPSGATE ST. SEPULCHRE WITH CHRIST CHURCH, GREYFRIARS AND ST. LEONARD, FOSTER LANE OTHBURY AND ST. STEPHEN, COLEMAN STREET WITH ST. CHRISTOPHER LE STOCKS, ST. BARTHOLOMEW-BY-THE-EXCHANGE, ST. OLAVE, OLD JEWRY, ST. MARTIN POMEROY, ST. MILD ST. HELEN, BISHOPSGATE WITH ST. ANDREW UNDERSHAFT AND ST. ETHELBURGA, BISHOPSGATE AND ST. MARTIN OUTWICH AND ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL ex. par ST. BOTOLPH, ALDGATE AND HOLY TRINITY, MINORIES ST. EDMUND-THE-KING & ST. MARY WOOLNOTH W ST. NICHOLAS ACONS, ALL HALLOWS, LOMBARD STREET ST. BENET, GRACECHURCH, ST. LEONARD, EASTCHEAP, ST. DONIS, BA ST. ANDREW-BY-THE-WARDROBE WITH ST. ANN BLACKFRIARS ST. CLEMENT, EASTCHEAP WITH ST. MARTIN ORGAR ST. JAMES GARLICKHYTHE WITH ST. MICHAEL QUEENHITHE AND HOLY TRINITY-THE-LESS T OF THE SAVOY ex. par ALL HALLOWS, BERKYNCHIRCHE-BY-THE-TOWER WITH ST. DUNSTAN-IN-THE-EAST WITH ST. CLEMENT DANES det. 1 THE TOWER OF LONDON ST. PETER, LONDON D Copyright acknowledgements These maps were prepared from a variety of data sources which are subject to copyright. Census data Source: National Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk -

Discovering Fraser Residence Bishopsgate

DISCOVERING FRASER RESIDENCE BISHOPSGATE “Imagine a world where you can enjoy the very best features of a world-class hotel with all the advantages CONTENTS 01 HOME of your very own apartment. Explore the following 02 INTRODUCTION pages to discover what makes staying at Fraser Residence 03 LOCATION Bishopsgate such a uniquely rewarding experience.” 04 APARTMENT FEATURES 05 SERVICES & FACILITIES 06 CONTACT US « 1 of 6 » Introduction Fraser Residence Bishopsgate, formerly known as The Writers is the latest addition to the Fraser collection in the City of London. Nestled in a historic street off the busy Bishopsgate, this stunning residence comprises 26 well-appointed designed contemporary and airy apartments ranging from Studios, One and Two bedroom apartments. Each of the apartments is fitted with the finest wood flooring, fully-fitted bathrooms and furnished with beautifully appointed contemporary furniture. Colourful accents and the most superb fittings set the scene for effortless relaxation during your business or leisure stay. A few minutes walk away from Liverpool Street Station and in the shadow of Old Spitalfields, one of London’s most historic markets, Fraser Residence Bishopsagte is amongst the finest and most desirable properties in the City. With a host of restaurants, coffee shops and bars in the immediate vicinity, as well as galleries, shops and the famous Brick Lane, the property offers the ideal location to combine business with pleasure. Our Vision Frasers Hospitality aims to be the premier global leader in the extended stay market through our commitment to continuous innovation in answering the unique needs of every customer. « 2 of 6 » Sun St Bishopsgate Location South Pl Spitalfields Moorgate Broadgate Rail Circle Nearest Underground: sbu Artillery Lane Find ry C London Moorgate i P Liverpool Street Station: - is served by the Circle, Central, rc Liverpool etti u coa s Street t Hammersmith and Metropolitan lines. -

Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4JQ

124 Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4JQ Charming self-contained Charming self-contained warehouse style office warehouse style office freehold with its own freehold with its own courtyard & rear garden courtyard & rear garden For Sale For Sale The Opportunity • Character Clerkenwell freehold, close to Smithfield, Farringdon and Barbican • Converted warehouse office building comprising a Net Internal Area of 4,981 sq ft (462.7 sq m) and a Gross Internal Area of 6,173 sq ft (573.5 sq m) • B1 officese u throughout • Exclusive private gated courtyard providing secure car parking for up to 3 cars • Secluded rear walled garden of approx. 1,500 sq ft • Attractive 1st floor terrace of approx. 600 sq ft • Potential to extend subject to securing the necessary consents • Sold with vacant possession on completion • Offers are invited for the freehold interest to include the front courtyard & rear garden Garden Lower Ground Floor Ground Floor Ground Floor Front Entrance The Location Connectivity The building sits in a cul-de-sac off Aldersgate Street with Charterhouse Square to the Barbican Station is within a minutes walk giving access to the Circle, west and Carthusian Street to the south. Clerkenwell Road is 300 metres to the north. Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan Lines. Farringdon Station is within 500 metres (7 minute walk) and is served by the same Tube lines, The immediate area benefits from the amenities of Smithfield Market and Clerkenwell Thameslink and Crossrail (from 2018). St Paul’s Station is a 10 minute walk Green, with a plethora of shops, bars and restaurants. The Barbican Centre, London to the south providing access to the Central Line. -

Etc.Venues 155 Bishopsgate EC2M 3YD

Exhibitor Information etc.venues 155 Bishopsgate EC2M 3YD Introduction We would like to officially welcome you to etc.venues located on the first floor of 155 Bishopsgate, in the heart of the City of London. We have prepared this guide to help you in the planning process prior to your event and to eliminate any surprises ahead of your arrival to the venue. By following the guidelines in this pack, the process should be as smooth as possible. Contents Deliveries & Collections .......................................................................................................................... 1 Tenancy Times ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Loading Bay ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Articulated Lorries ................................................................................................................................... 2 Client Delivery / Collection Forms .......................................................................................................... 2 Larger Build Stands ................................................................................................................................. 3 Access to Goods Lift ................................................................................................................................ 3 Out of Hours ........................................................................................................................................... -

The London Gazette, Issue 11671, Page 4

Sii<> Certificate -will be allowed and confirmed as the said Act Andrew Robinson, formerly of Hutwo.;:h In the County of directs, unless Cause be sliewn to the contrary on or before the Durham, late of Alder'gate-street, London, Gentleman. 45th of' Jiine instant.- William Millar, formerly of Kinj-street St. Giles's in the 'He-reas the acting Commissioners in the Commission Fields, U:e of Cumberland-stie^t ne :r the Middlesex Hos= W ^of Bankrupt awarded againft Isaac Thornton; of Fleet- pital, both in Middlesex, Grocer and Cheesemonger. streets London, Wine and Brandy Merchant, Dealer' and Peter Hardcastle, lorn-.erly of White Hart-vard Catherine- Chapman, have certified to the Right Hon. Henry Earl Da- street in the Strand in the County of Middlesex, Jace of thurst, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, that said Isaac H irplane Tcwer-street, London, Cooper. Thornton- hath in all Things conformed according to the Direc James Stiel, formerly of Sa.isbury-court in the Pari/h of St» tions Of the several Acts of Parliament made concerning Bank Bride in the City of London, late of Mary Le Bone High-*> rupt* J This is to give Notice, that by virtue of an Act passed street in the County of Middlesex, Gentlrman. -in the Fifth Year of his late Majesty's Reign, his Certificate James Proud love, formerly of Giey Eagle-stree, late of •will be allowed and confirmed, as tbe said Act directs, unleis Wheeler-street in the Parish of Christ Church Spitalfields in Cause* be Ihewii to the contrary on or before the 25th of June the Counry of Middlesex, instant.