Report UK Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book 5 Development Partners

República Democrática de Timor-Leste State Budget 2017 Approved Development Partners Book 5 “Be a Good Citizen. Be a New Hero to our Nation” Table of Contents Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Part 1: Development Assistance in Combined Sources Budget 2017 ..................... 4 Part 2: National Development Plans .................................................................................. 4 2.1 Strategic Development Plan 20112030 .............................................................................. 4 2.1 Program of the 6th Constitutional Government 20152017 ......................................... 5 2.3 The New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States ............................................................... 6 2.3.1 SDG and SDP Harmonization ........................................................................................................... 7 2.3.2 Timor‐Leste’s Second Fragility Assessment ............................................................................. 8 Part 3: Improved Development Partnership ............................................................... 10 3.1 Development Partnership Management Unit ................................................................. 10 3.2 Aid Transparency Portal (ATP) ........................................................................................... 10 Part 4: Trend of Development Assistance to TimorLeste ..................................... -

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD3216 INTERNATIONAL

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD3216 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 42.5 MILLION (US$59.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF TIMOR-LESTE FOR A TIMOR-LESTE BRANCH ROADS PROJECT November 1, 2019 Transport Global Practice East Asia And Pacific Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective June 30, 2019) Currency Unit = United States Dollar (US$) SDR 0.71932 = US$1 US$1.39021 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Vice President: Victoria Kwakwa Country Director: Rodrigo A. Chaves Regional Director: Ranjit Lamech Practice Manager: Almud Weitz Task Team Leader(s): Rodrigo Archondo-Callao, Elena Y. Chesheva ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic ADB Asian Development Bank ADN Agência de Desenvolvimento Nacional (National Development Agency) CAFI Conselho de Administração do Fundo Infraestrutura (Council for the Administration of the Infrastructure Fund) CERC Contingent Emergency Response Component CESMP Contractor’s Environmental and Social Management Plan CO2 Carbon Dioxide DA Designated Account DED Detailed Engineering Design DFAT Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade DG Director General DRBFC Directorate of Roads, Bridges and Flood Control EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP Environmental Management Plan -

Quarterly Report: October - December 2019 Usaid’S Avansa Agrikultura Project

QUARTERLY REPORT: OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2019 USAID’S AVANSA AGRIKULTURA PROJECT February 3, 2020 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cardno Emerging Markets USA, Ltd. (Cardno) for USAID’s Avansa Agrikultura Project, Contract number AID-472-C-15-00001. QUARTERLY REPORT: OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2019 USAID’S AVANSA AGRIKULTURA PROJECT Submitted by: Cardno Emerging Markets USA, Ltd. Submitted to: USAID/Timor-Leste Contract No.: AID-472-C-15-00001 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID’s Avansa Agrikultura Project Contents ACRONYMS............................................................................................................................................................................III 1.INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................................................. 6 2. REPORTING PERIOD HIGHLIGHTS............................................................................................................................ 7 2.1. SUB-PURPOSE 1 – IMPROVED ABILIT Y OF TIMORESE CIT IZENS T O ENGAGE IN ECONOMIC ACT IVIT IES ..............7 Output 1: Market Linkages Improved and Expanded Across the Horticulture Value Chain ......................... 7 2.2. SUB-PURPOSE 2 – INCREASED PRODUCTIVITY OF SELECTED HORTICULTURAL -

Urgent Safeguarding List with International Assistance

Urgent Safeguarding List with International Assistance ICH-01bis – Form LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING WITH INTERNATIONAL ASSISTANCE FROM THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE FUND Deadline 31 March 2020 for a possible inscription and approval in 2021 The ICH-01bis form allows States Parties to nominate elements to the Urgent Safeguarding List and simultaneously request International Assistance to support the implementation of the proposed safeguarding plan. Instructions for completing the nomination and request form are available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/forms Nominations and requests not complying with those instructions and those found below will be considered incomplete and cannot be accepted. New since 2016 cycle: request International Assistance when submitting a nomination for the Urgent Safeguarding List To nominate an element for inscription on the Urgent Safeguarding List and simultaneously request International Assistance to support the implementation of its proposed safeguarding plan, use Form ICH-01bis. To nominate an element for inscription on the Urgent Safeguarding List without requesting International Assistance, continue to use Form ICH-01. A. State(s) Party(ies) For multinational nominations and requests, States Parties should be listed in the order on which they have mutually agreed. Timor-Leste Form ICH-01bis-2021-EN – revised on 18/06/2019– page 1 B. Name of the element B.1. Name of the element in English or French Indicate the official name of the element that will appear in published material. Not to exceed 200 characters Tais, traditional textile B.2. Name of the element in the language and script of the community concerned, if applicable Indicate the official name of the element in the vernacular language, corresponding to its official name in English or French (point B.1.). -

A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste

2019 A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste 2018: A A Journal Journal of Changeof Change in Timor-Leste in Timor-Leste 2019 A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste 2018: A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste A Journal of Change in Timor-Leste is an annual publication of UNICEF Timor-Leste. Data in this report are drawn from the most recent available statistics from UNICEF and other United Nations agencies, and the Government of Timor-Leste. Cover photograph: © UNICEF Timor-Leste/2019/BSoares Girls take part in the ‘Kick for Identity’ junior football match to promote birth registration in Timor-Leste. © UNICEF Timor-Leste/2019/Helin THREE DECADES OF CHILD RIGHTS This has been a significant year for Timor-Leste. The 30th of August 2019 marked 20 years since the Popular Consultation, the countrywide vote that eventually led to the restoration of the country’s independence in 2002. The two decades that followed this momentous day have had their challenges, but have seen Timor- Leste achieve many milestones. The proportion of Timorese living in poverty reduced from 50 per cent in 2007 to 42 per cent in 2014. However, 49 per cent of children between the ages of 0 and 14 live below the national poverty line as of 2014. Undoubtedly, there is much work that still needs to be done. Towards this goal, UNICEF has worked closely with the Government of Timor- Leste, partners and donors to accelerate progress for children in the country: through the provision of technical and policy advice; advocacy; and supporting modeling initiatives or larger nationwide actions that draw attention to issues children face, drive change, and support actions that can catalyze progress. -

Mid-Term Review Report

“Strengthening Community Resilience to Climate-induced disasters in the Dili to Ainaro Road Development Corridor, Timor-Leste (DARDC)” Timor-Leste Mid-Term Review Report GEF Agency: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) National Disaster Management Directorate (NDMD) under the Implementing Partner: Ministry of Social Solidarity (MSS) and the Directorate for Forestry under the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAF) Funding: GEF-LDCF Focal Area: Climate Change Adaptation GEF Project ID: 5056 Region: Asia and Pacific UNDP PIMS: 5108 UNDP Atlas Project ID: 00081757 Project Timeline: August 2014 - July 2018 Submitted by: Jean-Joseph Bellamy & Anderias Tani Submitted on: August 23, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................................. II LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................... III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... IV 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2. CONTEXT AND OVERVIEW OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................... 6 3. REVIEW FRAMEWORK ....................................................................................................................................... -

Inception Report-Support for Preparation of a National Coffee

Inception Report Support for Preparation of a National Coffee Sector Development Plan for Timor-Leste Prepared by Coffee Quality Institute Date: December 10, 2017 This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government of Timor- Leste, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. List of Acronyms ASYCUDA Automated System for Customs Data ADB Asian Development Bank ATT Alter Trade Timor AusAid Australian Agency for International Development CBB Coffee Berry Borer CCT Cooperativa Café Timor COCAMAU Cooperativa Agrikultura Moris Foun Unidade Kafe Nain Maubisse CQI Coffee Quality Institute DNEDCA National Directorate of Extension and Agricultural Community Dev DNCPI Direcção Nacional de Café e Plantas Industriais ETCI East Timor Coffee Institute GAPs Good Agricultural Practices HDT Hibrido de Timor Kg Kilogram MAF Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries MECAE Ministru Estadu koordenador asuntus Ekonomia MCIA Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Environment MTC MTC Group, Australia NCBA National Cooperative Business Association NGO Non-Governmental Organization PARCIC Pacific Area Resource Center Interpeoples’ Cooperation RDP Rural Development Program SAPT Sociedade Agrícola Pátria e Trabalho SMART Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Timed SOL Seeds of Life SWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats TA Technical Assistance UNTAET United Nations Transitional Administration for East Timor UNTL National University of Timor-Leste WCR World Coffee Research i Preface This document is the Inception Report for the ADB-funded TA-9264 Support for Preparation of a National Coffee Sector Development Plan. The Inception Report draws upon the consultations and analytical work conducted by the TA team of consultants in collaboration with senior officers from Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAF), Asian Development Bank (ADB) staff, private sector companies, producers, educators, donor partners, and non-governmental organization (NGO) collaborators. -

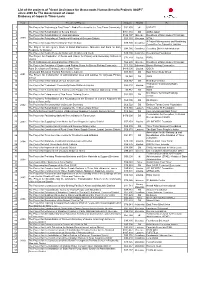

List of the Project of GGP 2000-2020

List of the projects of "Grant Assistance for Grass-roots Human Security Projects (GGP)" since 2000 by The Government of Japan Embassy of Japan in Timor-Leste Year The title of Project Amount District By 1 The Project for "Listening to East Timor" - Radio Receivers for the East Timor Community $91,850 all UNTAET 2 The Project for Rehabilitation of Becora School $151,934 Dili ADRA Japan 3 The Project for Rehabilitation of Laga Orphanage $146,107 Baucau Daughters of Mary Help of Christians 4 2000 The Project for Rebuilding of Traditional Weaving of Oecusse District $23,135 Oecusse IKTALI A Project Management and Monitoring 5 The Project for Carpentry Training for Youth in Suai $89,700 Covalima Committee for Carpentry Training The Project for Emergency Stock of Road Maintenance Materials and Fund for Early 6 $94,786 Covalima Covalima District Administration Response for Disaster 7 The Project for Build a Peaceful Nation with Children and Youth $80,200 6 districts Deo Gratias Foundation The Project for Production of Desks and Chairs for Primary and Secondary Schools in 8 $72,118 Liquica PARC Liquica 9 The Rehabilitation of Laga Orphanage (Phase II) $66,295 Baucau Daughters of Mary Help of Christians 10 The Project for Provision of Engines and Fishing Gears for Biacou Fishing Cooperative $15,192 Bobonaro Biacou Fishing Cooperative 11 Rural Development Training Center in East Timor $410,000 Liquica OISCA 12 Library and Education Training Facility Development $88,588 Dili East Timor Study Group 2001 The Project for Construction of Administration -

A Case Study of East Timor James Scambary and Todd Wassel

11 Hybrid Peacebuilding in Hybrid Communities: A Case Study of East Timor James Scambary and Todd Wassel Introduction East Timor achieved independence in 1999 after 24 years of brutal Indonesian military occupation and more than 400 years of Portuguese colonial rule. With the aid of an international peacekeeping force, a United Nations (UN) mission installed an interim administration that set about preparing East Timor for self-governance. However, while its new-found freedom was much celebrated, persistent tensions, rather than unity and peace, came to characterise East Timor’s society in the post-independence period. These tensions reached a peak in what is now popularly referred to as the ‘Crisis’. From April to June 2006, a rapid series of events resulted in the unravelling of the six-year UN statebuilding project. National- level political tensions and divisions within the security services served as a catalyst for a wider communal conflict on a national scale, which was to last for nearly two years. In response, a comprehensive, national-level donor and government effort was rolled out to address the perceived causes of this conflict, and get internally displaced people back into their communities. These largely generic, top-down responses included an intensive community mediation campaign and a raft of programs to improve educational and employment 181 HYBRIDITY ON THE GROUND IN PEACEBUILDING AND DEVELOPMENT opportunities. Nonetheless, sporadic communal conflict persisted and, by early 2009, began to increase in both urban and rural areas. Clearly, the sources of violence were more complex and deeply rooted than thought. Longer-term approaches were needed with more local ownership, which would in turn require more hybrid strategies to engage with traditional social structures. -

Infrastructure Fund Portfolio 4 1

República Democrática de Timor-Leste Infrastructure Fund Book 3A “Be a Good Cizen. Be a New Hero to our Naon” TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 I. INFRASTRUCTURE FUND PORTFOLIO 4 1. AGRICULTURE PROGRAM 5 2. WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM 5 3. URBAN AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 6 4. ELECTRICITY PROGRAM 6 5. PORT PROGRAM 7 6. AIRPORT PROGRAM 7 7. MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS PROGRAM (MDG) 8 8. TASI MANE PROGRAM 8 9. EXTERNAL LOANS PROGRAM 9 10. FINANCIAL SYSTEM AND SUPPORTING INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM 9 11. INFORMATICS PROGRAM 10 12. YOUTH AND SPORTS PROGRAM 10 13. HEALTH PROGRAM 11 14. TOURISM PROGRAM 11 15. EDUCATION PROGRAM 12 16. SOCIAL SOLIDARITY PROGRAM 12 17. BRIDGES PROGRAM 12 18. SECURITY AND DEFENCE PROGRAM 13 19. ROAD PROGRAM 13 20. PUBLIC BUILDINGS PROGRAM 14 21. PREPARATION OF DESIGNS AND PROVISION OF SUPERVISION SERVICES 14 22. MAINTENANCE AND REHABILITATION PROGRAM 14 II. IF BUDGET SUMMARY 15 III. ANNEXES 17 2 | P a g e Rectification Budget Book 3A – Infrastructure Fund 2017 INTRODUCTION The infrastructure development is one of the key national priorities for strategic investment in Timor- Leste. According to the Strategic Development Plan 2011 – 2030, a central pillar of the long-term development is the building and maintenance of core and productive infrastructure that will be able to support and enhance social and economic growth that leads to a better quality of life. The main objective of the Infrastructure Fund is to support strategic projects for further growth of Timor- Leste’s economy. The Infrastructure Fund is the main governmental instrument which was established in 2011 in order to facilitate infrastructure development and provide financial sources for roads and bridges, airports and seaports, power and water supply, education and health, tourism and other major projects with budget over than $1 million which have significant impact to the country. -

Infrastructure Fund

República Democrática de Timor-Leste Infrastructure Fund Book 3A TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword …………………………………..........…………………..…………………………………………… 3 1. IF POLICY, STANDARDS AND REGULATION 4 1.1. IF Objective and Priorities ………..……………………………………………….…………….…… 4 1.2. IF Budget Allocation and Execution ……………………………………………….………..…… 7 1.3. Legal Regulation Framework …………………………………………………………..…………… 8 1.4. Institutional Arrangements ……………………………………….……………………………..…. 9 1.5. Project Implementation and IF Workflow ……………………………………………………. 10 1.6. Project Standards …………………………………………………………….……………………..…… 12 Feasibility Study ……………………………………………………………………………..…………… 12 Project Appraisal …………………………………………………………………………………….…… 12 Ex‐post Evaluation …………………………………………………………………………….………… 14 2. INFRASTRUCTURE FUND PORTFOLIO 15 2.1. Agriculture Program ……………………………………………………………..………………… 16 2.2. Water and Sanitation Program …………………………………………..…………………… 16 2.3. Urban and Rural Development Program …………………………………………….…… 17 2.4. Electricity Program …………………………………………………………………………….…… 17 2.5. Ports Program ………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 2.6. Airports Program ……………………………………………………………………………………. 18 2.7. Tasi Mane Program ………………………………………………………………………………… 19 2.8. Financial System and Supporting Infrastructure ……………………………………… 19 2.9. Information System Program …………………………………………………………………. 20 2.10. Youth and Sports Program ……………………………………………………………………… 20 2.11. Health Program ………………………………………………………………………………….…… 21 2.12. Tourism Program ……………………………………………………………………………….…… 21 2.13. Education Program …………………………………………………………………………………. -

View Proceeding

PROCEEDING 4th INTERNATIONAL GEOSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON TIMOR - LESTE GEOLOGICAL RESOURCES DATA AND INFORMATION FOR ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION AND DEVELOPMENT Dili, 23 - 26 October 2018 Rua Delta 1, Aimutin, Comoro, Supported by: Dili, Timor - Leste Contact No. (+670) 3310 179 www.ipg.tl 4th IPG International Geosciences Conference on Timor-Leste Geological Resources Data and Information for Economic Diversification and Development Dili, 23 – 26 October 2018 PROCEEDING 4th IPG International Geosciences Conference on Timor- Leste Geological Resources Data and Information for Economic Diversification and Development Responsible President of IPG, H.E. Helio Casimiro Guterres, M.Sc Instituto do Petróleo e Geologia – Instituto Público (IPG), Rua : Delta 1, Aimutin, Comoro, Dili, Timor-Leste Phone: (+670)3310-179, Website: www.IPG.tl Supported by Copyright @ 2018 i 4th IPG International Geosciences Conference on Timor-Leste Geological Resources Data and Information for Economic Diversification and Development Dili, 23 – 26 October 2018 4th IPG International Conference Organizing Committee NAME RESPONSIBILITY Jorge Rui de Carvalho Martins President of the Organizing Committee João Jeronimo Administration and Finance Coordinator Members : 1. Divaia Cabral 2. Albino Amaral 3. Maria Piedade 4. Noemia Guterres 5. Mario Maia 6. Anabela Ximenes 7. Luis dos Santos 8. Aleixo Tavares 9. Francisco Martins Oliveira 10. João da Ressureição Canito 11. João Alek Hornai 12. Luis Ximenes 13. Julio Antonio Soares Tlale 14. Madalena Soares 15. Maria G. Sarmento 16. Maria do Rego 17. Pedro Hornai 18. Zacarias Quintão de Jesus 19. Celestina de Jesus Freitas Volunteers : 1. Arsenia de D. Soares 2. Dircia Maria Pacheco 3. Leocadia Catarina de Jesus Soares 4. Luduvina Pereira Guterres 5.