The Gray Wolf Under the Endangered Species Act (ESA): a Case Study in Listing and Delisting Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shape Evolution and Sexual Dimorphism in the Mandible of the Dire Wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho La Brea Alexandria L

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2014 Shape evolution and sexual dimorphism in the mandible of the dire wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho la Brea Alexandria L. Brannick [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Brannick, Alexandria L., "Shape evolution and sexual dimorphism in the mandible of the dire wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho la Brea" (2014). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 804. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAPE EVOLUTION AND SEXUAL DIMORPHISM IN THE MANDIBLE OF THE DIRE WOLF, CANIS DIRUS, AT RANCHO LA BREA A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences by Alexandria L. Brannick Approved by Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, Committee Chairperson Dr. Julie Meachen Dr. Paul Constantino Marshall University May 2014 ©2014 Alexandria L. Brannick ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my advisor, Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, for all of his help with this project, the many scientific opportunities he has given me, and his guidance throughout my graduate education. I thank Dr. Julie Meachen for her help with collecting data from the Page Museum, her insight and advice, as well as her support. I learned so much from Dr. -

La Brea and Beyond: the Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas

La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas Edited by John M. Harris Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series 42 September 15, 2015 Cover Illustration: Pit 91 in 1915 An asphaltic bone mass in Pit 91 was discovered and exposed by the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art in the summer of 1915. The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History resumed excavation at this site in 1969. Retrieval of the “microfossils” from the asphaltic matrix has yielded a wealth of insect, mollusk, and plant remains, more than doubling the number of species recovered by earlier excavations. Today, the current excavation site is 900 square feet in extent, yielding fossils that range in age from about 15,000 to about 42,000 radiocarbon years. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Archives, RLB 347. LA BREA AND BEYOND: THE PALEONTOLOGY OF ASPHALT-PRESERVED BIOTAS Edited By John M. Harris NO. 42 SCIENCE SERIES NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Luis M. Chiappe, Vice President for Research and Collections John M. Harris, Committee Chairman Joel W. Martin Gregory Pauly Christine Thacker Xiaoming Wang K. Victoria Brown, Managing Editor Go Online to www.nhm.org/scholarlypublications for open access to volumes of Science Series and Contributions in Science. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Los Angeles, California 90007 ISSN 1-891276-27-1 Published on September 15, 2015 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas PREFACE Rancho La Brea was a Mexican land grant Basin during the Late Pleistocene—sagebrush located to the west of El Pueblo de Nuestra scrub dotted with groves of oak and juniper with Sen˜ora la Reina de los A´ ngeles del Rı´ode riparian woodland along the major stream courses Porciu´ncula, now better known as downtown and with chaparral vegetation on the surrounding Los Angeles. -

Second Song for Many (2019)

second song for many (2019) Tim PARKINSON Sample performance for Not Copyright 2019 © Tim Parkinson second song for many (2019) for any number of instrumentalists (ideally at least 5 to 20) The score consists of 75 bars of 6’ each, in sections listed A-O, for Audio Track, Continuo, and Ensemble with Conductor. A Conductor uses a stopwatch to signal each bar. Audio Track - A 1” beep (f5) every 30”, beginning at the second before 0’00”. The beeps may act as an audio cue for each section (except for the central sections F-J where they continue strictly in 30” intervals). This part may be prerecorded audio track, or may be performed live by one person playing an electronic beep (sine tone or other waveform on a keyboard) using a stopwatch to keep strict time. Continuo - Instrument may be any type of keyboard, (e.g. piano/electric keyboard/accordion/reed organ); or 2 keyboards; or treble clef may be keyboard and bass clef a pair of matching instruments (e.g. 2 clarinets/2 bassoons/2 violas/cellos) Treble clef melody plays quietly, legato and continuously from start to finish. Bass clef chords may be held until the next, or there may be rests in between. For both clefs the rhythm is very approximate, imprecise, irregular. Notation given is approximate number of notes per unit. Meandering, hesitating, for itself. The continuo may be positioned separately from the ensemble, to one side, but not offstage. Ensemble - Texts are given to provide rhythms for tapping on instruments (A-E), with stones (K-O), and for whispering. -

Wolf (Dier) 1 Wolf (Dier)

Wolf (dier) 1 Wolf (dier) Wolf [1] IUCN-status: Veilig (2008) Liggende wolf Taxonomische indeling Rijk: Animalia (Dieren) Stam: Chordata (Chordadieren) Klasse: Mammalia (Zoogdieren) Orde: Carnivora (Roofdieren) Familie: Canidae (Hondachtigen) Geslacht: Canis Soort Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758 Verspreidingsgebied wolf (huidige verspreiding in het groen, voormalige verspreiding in het rood) Wolf Afbeeldingen Wolf Wolf (dier) 2 Wolf op Wikispecies De wolf (Canis lupus) is een roofdier uit de familie der hondachtigen (Canidae). Het is naar alle waarschijnlijkheid de voorouder van de hond (Canis lupus familiaris). In ieder geval kunnen ze samen vruchtbare nakomelingen voortbrengen, zodat de hond en de wolf, althans volgens bepaalde definities, tot dezelfde soort kunnen worden gerekend. Kenmerken: uiterlijk en fysiologie De wolf heeft een grijze tot grijzige vacht, met een rossig bruine kleur op rug, kop en oren. De verschillen tussen individuele wolven en ondersoorten zijn echter groot en ze komen in allerlei kleurvariëteiten voor, van geheel wit via roodbruin tot geheel zwart. Wolven hebben een kop-romplengte van 80 tot 160 cm, en een staart van 30 tot 50 centimeter. De schouderhoogte is 65 tot 80 centimeter. Vrouwtjes zijn zo'n tien procent kleiner dan mannetjes: mannetjes wegen 20 tot 80 kg, vrouwtjes worden gemiddeld 18 tot 50 kg zwaar. De wolf heeft in rust een hartslag van 90 slagen per minuut en een ademhalingsfrequentie van 15 tot 20 per minuut. Bij grote inspanning kan dit oplopen tot een hartslag van 200 per minuut en een ademhalingsfrequentie van 100 per minuut. Het gehoor, de reukzin en het zichtvermogen zijn goed ontwikkeld. Een wolf kan tegen de wind in andere dieren ontdekken die zich op een afstand van 300 meter van hem bevinden. -

Download Scriptie

Dissertation 2011-2012 Vanessa Almeida da Silva Amorim Wolf V Dog – Predator V Pet 4 BDAO Titel Predator V Pet – the difference between wolves and dogs Abstract Dogs play a prominent role in modern day society. Most of them are kept for companionship which translates into a very close dog-human relationship. Canis familiaris have adapted incredibly well to man-made society however with an increasing number of cases ending up in shelters it is fair to say that this subject still needs further exploration. A lot has been written about the way dogs behave and how owners can improve their relationship with their pet. A very popular vision on dog behaviour is the wolf pack theory also called lupomorphism. For a long time the interpretation of this vision consisted in the need for a dog owner to be a leader by any means. If an owner is not strong enough as a leader a dog will try to take over this role and show behaviour that is not desirable. Recent studies have shown that there are gaps in this theory. The vision on how a wolf pack functions has changed and there is an increasing number of experts that agree that the best study subject for dog behaviour is in fact the dog itself. The goal of this thesis is to clarify how dogs and wolves relate to each other as species both biologically and psychologically. A lot of literature research has gone into this thesis to try and find out what really goes on inside a dog’s head and if comparing them to wolves is useful to grasp that idea. -

FEIS Citation Retrieval System Keywords

FEIS Citation Retrieval System Keywords 29,958 entries as KEYWORD (PARENT) Descriptive phrase AB (CANADA) Alberta ABEESC (PLANTS) Abelmoschus esculentus, okra ABEGRA (PLANTS) Abelia × grandiflora [chinensis × uniflora], glossy abelia ABERT'S SQUIRREL (MAMMALS) Sciurus alberti ABERT'S TOWHEE (BIRDS) Pipilo aberti ABIABI (BRYOPHYTES) Abietinella abietina, abietinella moss ABIALB (PLANTS) Abies alba, European silver fir ABIAMA (PLANTS) Abies amabilis, Pacific silver fir ABIBAL (PLANTS) Abies balsamea, balsam fir ABIBIF (PLANTS) Abies bifolia, subalpine fir ABIBRA (PLANTS) Abies bracteata, bristlecone fir ABICON (PLANTS) Abies concolor, white fir ABICONC (ABICON) Abies concolor var. concolor, white fir ABICONL (ABICON) Abies concolor var. lowiana, Rocky Mountain white fir ABIDUR (PLANTS) Abies durangensis, Coahuila fir ABIES SPP. (PLANTS) firs ABIETINELLA SPP. (BRYOPHYTES) Abietinella spp., mosses ABIFIR (PLANTS) Abies firma, Japanese fir ABIFRA (PLANTS) Abies fraseri, Fraser fir ABIGRA (PLANTS) Abies grandis, grand fir ABIHOL (PLANTS) Abies holophylla, Manchurian fir ABIHOM (PLANTS) Abies homolepis, Nikko fir ABILAS (PLANTS) Abies lasiocarpa, subalpine fir ABILASA (ABILAS) Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica, corkbark fir ABILASB (ABILAS) Abies lasiocarpa var. bifolia, subalpine fir ABILASL (ABILAS) Abies lasiocarpa var. lasiocarpa, subalpine fir ABILOW (PLANTS) Abies lowiana, Rocky Mountain white fir ABIMAG (PLANTS) Abies magnifica, California red fir ABIMAGM (ABIMAG) Abies magnifica var. magnifica, California red fir ABIMAGS (ABIMAG) Abies -

Plio/Pleistocene Wolves

Evolution of the brain of Plio/Pleistocene wolves Evolution of the brain of Plio/Pleistocene wolves George Lyras Alexandra van der Geer Michael Dermitzakis Summary Caninae be divided three the the foxes and the SouthAmerican The living subfamily can roughly into groups: dogs, canids, which started to diverge somewherein the Miocene.Here theevolution ofthe dogs is dealtwith, starting with the which in North America the Middle and the Old World. genus Eucyon, originated during Miocene, spread over During the Pleistocene, the dogs were abundant in Eurasia, with as most well-knownrepresentative the Etruscan Canis and the Late Pleistocene the Canis The evolution of the is wolf, etruscus, later, during gray wolf, lupus. dogs thebasis oftheevolutionoftheir cerebrum. The of and folds the make followedon specific patterns grooves on cortex the inner side of the neurocranium. of this inner this is revealed. The an impression on By making a cast side, pattern authors madesuch casts (endocasts) of all living dogs and red foxes, plus a number of fossil species and compared them It that foxes ofthe have short and a of mutually. appears Vulpes-lineage a prorean gyrus, penthagon-like pattern the have broad and grooves on sensory-motor region. Dogs (Canis, Cuon, Lycaon ) a long, bilaterally compressed and of the the to be rather prorean gyrus, an orthogonal pattern grooves on sensory-motor region. Eucyon appears differ close to the Vulpes-pattern, whereas Canis lepophagus is very similarto living Canis. Vulpes stenognathus doesn’t significantly from the living Vulpes. Samenvatting onderfamilie kan verdeeld drie de de de De huidige Cartinae grofweg worden in groepen: honden, vossen en Zuid-Amerikaanse diezich elkaar scheiden in het Mioceen. -

Endangered Species Technical Bulletin

March 1977 Vol. II, No. 3 ENDANGERED •ft * SPECIES TECHNICAL BULLETIN Department of the Interior • U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service • Endangered Species Program, Washington, D.C. 20240 ES Treaty Permits Required May 23; Enforcement Starts The United States will begin enforcing the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora on May 23, 1977. As of that date, permits or certificates will be required for international trade in all species listed in appendixes I, II, and III of the Convention. Regulations set- ting up a system for obtaining permits were published in the February 22,1977 Issue of the Federal Register. (Copies of the regulations are availa- ble from the Federal Wildlife Permit Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 20240.) A list of all the species protected by the Fish and Wildlife Service Photo by Don Reilly Convention is included with the permit regulations. This list is similar to the list of species protected by the Endangered Timber Wolf Reclassification Debated Species Act of 1973, but is not identical. Forexample, although Appendix II of the Management of the eastern timber Many of the biological issues concern- Convention lists all species of orchids, wolf (Canis lupus lycaon) has become a ing the future of the wolf have crystal- the act does not yet provide protection controversial issue in northern Minneso- lized with publicatiori of a draft recovery for plants. Furthermore, listing of more ta, the wolf's last stronghold in the Lower plan by the Eastern Timber Wolf Recov- than 1,850 plants under the act is 48 States. -

Mammal Collections of the Western Hemisphere

Journal of Mammalogy, 99(6):1307–1322, 2018 DOI:10.1093/jmammal/gyy151 Mammal collections of the Western Hemisphere: a survey and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/99/6/1307/5223777 by University of New Mexico, Jonathan Dunnum on 17 December 2018 directory of collections JONATHAN L. DUNNUM,* BRYAN S. MCLEAN, ROBERT C. DOWLER, AND THE SYSTEMATIC COLLECTIONS COMMITTEE OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MAMMALOGISTS1 Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA (JLD) Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA (BSM) Department of Biology, Angelo State University, San Angelo, TX 76909, USA (RCD) * Correspondent: [email protected] 1This committee included Sergio Ticul Alvarez-Castañeda, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste; Jeff E. Bradley, University of Washington; Robert D. Bradley, Texas Tech University; Leslie N. Carraway, Oregon State University; Juan P. Carrera-E., Texas Tech University; Christopher J. Conroy, University of California-Berkeley; Brandi S. Coyner, University of Oklahoma; John R. Demboski, Denver Museum of Nature and Science; Carl W. Dick, Western Kentucky University; Robert C. Dowler (Chair), Angelo State University; Kate Doyle, University of Massachusetts; Jonathan L. Dunnum, University of New Mexico; Jacob A. Esselstyn, Louisiana State University; Eliecer Gutiérrez, Universidade Federal de Santa María; John D. Hanson, RTL Genomics; Paula M. Holahan, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Thorvald Holmes, Humboldt State University; Carlos A. Iudica, Susquehanna University; Rafael N. Leite, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia; Thomas E. Lee, Jr., Abilene Christian University; Burton K. Lim, Royal Ontario Museum; Jason L. Malaney, Austin Peay State University; Bryan S. -

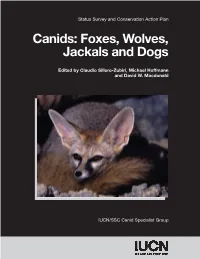

Canids: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan

IUCN/Species Survival Commission Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs Canids: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is one of six volunteer commissions of IUCN – The World Conservation Union, a union of sovereign states, government agencies and non- governmental organisations. IUCN has three basic conservation objectives: to secure the conservation of nature, and especially of biological diversity, as an essential foundation for the future; to ensure that where the Earth’s natural resources are used this is done in a wise, Canids: Foxes, Wolves, equitable and sustainable way; and to guide the development of human communities towards ways of life that are both of good quality and in enduring harmony with other components of the biosphere. Jackals and Dogs A volunteer network comprised of some 8,000 scientists, field researchers, government officials and conservation leaders from nearly every country of the world, the SSC membership is an unmatched source of information about biological diversity and its conservation. As such, SSC Edited by Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, Michael Hoffmann members provide technical and scientific counsel for conservation projects throughout the world and serve as resources to governments, international conventions and conservation and David W. Macdonald organisations. IUCN/SSC Action Plans assess the conservation status of species and their habitats, and specifies conservation priorities. The series is one of the world’s most authoritative sources of Survey and Conservation Action -

Paleoecology of the Large Carnivore Guild from the Late Pleistocene of Argentina

Paleoecology of the large carnivore guild from the late Pleistocene of Argentina FRANCISCO J. PREVOSTI and SERGIO F. VIZCAÍNO Prevosti, F.J. and Vizcaíno, S.F. 2006. Paleoecology of the large carnivore guild from the late Pleistocene of Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (3): 407–422. The paleoecology of the South American fossil carnivores has not been as well studied as that of their northern relatives. One decade ago Fariña suggested that the fauna of Río Luján locality (Argentina, late Pleistocene–early Holocene) is not balanced because the metabolic requirements of the large carnivores are exceeded by the densities and biomass of the large herbivores. This conclusion is based on the calculation of densities using allometric functions between body mass and population abundance, and is a consequence of low carnivore richness versus high herbivore richness. In this paper we review the carnivore richness in the Lujanian of the Pampean Region, describe the paleoecology of these species in− cluding their probable prey choices, and review the available information on taphonomy, carnivore ecology, and macroecology to test the hypothesis of “imbalance” of the Río Luján fauna. The carnivore richness of the Río Luján fauna comprises five species: Smilodon populator, Panthera onca, Puma concolor, Arctotherium tarijense, and Dusicyon avus. Two other species are added when the whole Lujanian of the Buenos Aires province is included: Arctotherium bonariense and Canis nehringi. With the exception of D. avus and Arctotherium, these are hypercarnivores that could prey on large mammals (100–500 kg) and juveniles of megamammals (>1000 kg). S. populator could also hunt larger prey with body mass between 1000 and 2000 kg. -

Making Room for Wolf Recovery: the Case for Maintaining Endangered Species Act Protections for America’S Wolves

Making Room for Wolf Recovery: The Case for Maintaining Endangered Species Act Protections for America’s Wolves ildlife for W 25 g Y in e v a a r S s Amaroq Weiss, Noah Greenwald, Curt Bradley November 2014 I. Executive Summary southern Rocky Mountains, Grand Canyon, Cascade Mountains in Washington, Oregon and California, In 2011 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removed the Sierra Nevada and the Adirondacks are all places Endangered Species Act protections for wolves in the that could support wolf populations. According to northern Rocky Mountains and western Great Lakes, the studies, these areas are capable of supporting a arguing that wolves were recovered in those regions minimum of 5,000 wolves, which would nearly double and the states could be trusted to manage them. But the existing wolf population. all of the states with substantial wolf populations have enacted aggressive hunting and trapping seasons that Recovering wolves to these additional areas is are intended to drastically reduce wolf populations. To necessary to ensure the long-term survival of gray date these hunts have resulted in the killing of more wolves in the lower 48 states and enrich the diversity than 2,800 wolves. The deaths of so many wolves of U.S. ecosystems that have lacked the gray wolf have contributed to declines in wolf populations of as a top predator for decades. At last count the three 9 percent in the northern Rockies and 25 percent in existing wolf populations combined include only Minnesota. Given increased efforts to kill wolves roughly 5,400 wolves, which is below what scientists in many states, these declines can be expected to have identified as the minimum viable population continue and likely increase.