The Virtual Landscape of Geological Information Topics, Methods, and Rhetoric in Modern Geology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uchicagomag-Spring20.Pdf

Is it possible to feel nostalgic the first time you visit a place? KIAWAH GETS YOU COVID-19 … BRENT STAPLES … RECESSION LIT … IMPROVING MEDICAL IMAGING … COACH OF COACHES A Curated Collection of Homes and Homesites with Club Memberships in the Heart of the South Carolina Lowcountry. kiawahisland.com/ivyleague | 866.312.1791 SPRING 2020 Obtain the Property Report required by Federal Law and read it before signing anything. No Federal or State agency has endorsed or judged the merits of value, if any, of this property. This is not intended to be an offer to sell nor a solicitation of offer to buy real estate in any jurisdiction where prohibited by law. This offer is made pursuant to the New York State Department of Law’s Simplified Procedure for Homeowners Associations with a De Minimis Cooperative Interest (CPS-7). The CPS-7 application (File No. HO16-0007) and related documents may be obtained from the sponsor. This project is registered with the State of New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance Real Estate Commission. Obtain and read the NJ Public Offering Statement before signing anything (NJ Reg#16-15-0011 and 0012). An affiliate of Kiawah Partners. SPRING 2020, VOLUME 112, NUMBER 3 UCH_Spring2020 cover and spine_v1.indd 1 5/15/20 11:46 AM 200319_Kiawah_Chicago.indd 1 1/30/20 8:54 AM UCH_ADS_v1.indd 2 5/13/20 1:16 PM EDITORˆS NOTES VOLUME 112, NUMBER 3, SPRING 2020 EDITOR Laura Demanski, AM’94 SENIOR EDITOR Mary Ruth Yoe FROM A DISTANCE ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susie Allen, AB’09 MANAGING EDITOR Rhonda L. -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

ILLINO S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. THE BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS JULY/AUGUST 1992 VOLUME 45 NUMBER 11 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS EXPLANATION OF CODE SYMBOLS USED WITH ANNOTATIONS * Asterisks denote books of special distinction. R Recommended. Ad Additional book of acceptable quality for collections needing more material in the area. M Marginal book that is so slight in content or has so many weaknesses in style or format that it should be given careful consideration before purchase. NR Not recommended. SpC Subject matter or treatment will tend to limit the book to specialized collections. SpR A book that will have appeal for the unusual reader only. Recommended for the special few who will read it. C.U. Curricular Use. D.V. Developmental Values. THE BULtum OF THE CENTER PO CmLDREN'S BOOKs (ISSN 0008-9036) is published monthly except August by The University of Chicago Press, 5720 S. Woodlawn, Chicago, Illinois, 60637 for The Centeor Children's Books. Betsy Hearnm Editor; Roger Sutton Executive Editor; Zena Sutherland, Associate Editor, Deborah Stevenson, Editorial Assistant. An advisory committee meets weekly to discuss books and reviews. The members are Alba Endicott, Robert Strang, Elizabeth Taylor, Kathryn Jennings, and Deborah Stevenson. Reviewers' initials are appended to reviews. SUBSCRI RATES:•oN 1 year, institutions, $32.00; individuals, $27.00; $24.00 per year for two or more subscriptions to the same address; Canada, $39.24. In countries other than the United States and Canada, add $5.00 per subscription for postage. -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

ILLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO * GRADUATE LIBRARY SCHOOL Volume 34 JULY-AUGUST, 1981 Number 11 New Titles for Children and Young People Aaseng, Nathan. Pete Rose; Baseball's Charlie Hustle. Lerner, 1981. 79-27377. ISBN 0- 8225-0480-4. 48p. illus. with photographs. $5.95. Like most biographies of sports figures, this is a medley of boyhood interest in Ad sports, experiences as a rookie player, the ups and downs of a professional career, 3-5 and action sequences or establishment of records. This hasn't the hyperbole that weakens many books about sports heroes, although it has a fair share of admiration, both for Rose's ability as a baseball player and for the aggressiveness that won him the nickname of "Charlie Hustle." The text is continuous, with neither table of contents nor index to give access to facts; there are no statistical tables included, but the book ends with photographs and statistics for each of the fifteen players who have had three thousand hits. Ahlberg, Janet. Funnybones; written by Janet and Allan Ahlberg. Greenwillow, 1981. 79- 24872. Trade ed. ISBN 0-688-80238-9; Library ed. ISBN 0-688-84238-0. 29p. illus. Trade ed. $8.95; Library ed. $8.59. What happens in the story is of less importance than the basic situation and the R way in which the story's told, in a book in comic strip format. -

A Late Archaic and Woodland Site in Northeastern Illinois Peter John Geraci University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2016 The rP ehistoric Economics of the Kautz Site: a Late Archaic and Woodland Site in Northeastern Illinois Peter John Geraci University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Geraci, Peter John, "The rP ehistoric Economics of the Kautz Site: a Late Archaic and Woodland Site in Northeastern Illinois" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1141. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1141 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PREHISTORIC ECONOMICS OF THE KAUTZ SITE: A LATE ARCHAIC AND WOODLAND SITE IN NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS by Peter J. Geraci A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree of Masters of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2016 ABSTRACT THE PREHISTORIC ECONOMICS OF THE KAUTZ SITE: A LATE ARCHAIC AND WOODLAND SITE IN NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS by Peter J. Geraci The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under The Supervision of Robert J. Jeske, Ph.D. The Kautz Site (11DU1) is a multi-component archaeological site located in the DuPage River Valley in northeastern Illinois. It was inhabited at least six different times between the Late Archaic and Late Woodland periods ca. 6000-1000 B.P. The site was excavated over the course of three field seasons between 1958 and 1961, but the results were never made public. -

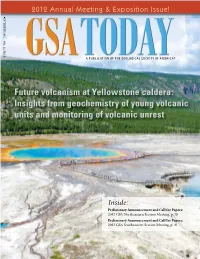

Future Volcanism at Yellowstone Caldera: Insights from Geochemistry of Young Volcanic Units and Monitoring of Volcanic Unrest

2012 Annual Meeting & Exposition Issue! SEPTEMBER 2012 | VOL. 22, NO. 9 A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA® Future volcanism at Yellowstone caldera: Insights from geochemistry of young volcanic units and monitoring of volcanic unrest Inside: Preliminary Announcement and Call for Papers: 2013 GSA Northeastern Section Meeting, p. 38 Preliminary Announcement and Call for Papers: 2013 GSA Southeastern Section Meeting, p. 41 VOLUME 22, NUMBER 9 | 2012 SEPTEMBER SCIENCE ARTICLE GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news and information for more than 25,000 GSA member read- ers and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (April/ May is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. 4 Future volcanism at Yellowstone GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, caldera: Insights from geochemistry regardless of race, citizenship, gender, sexual orientation, of young volcanic units and religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this monitoring of volcanic unrest publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Guillaume Girard and John Stix © 2012 The Geological Society of America Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright not claimed on content prepared Cover: View looking west into the Midway geyser wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of basin of Yellowstone caldera (foreground) and the West their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or request to GSA, to use a single Yellowstone rhyolite lava flow (background). -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Fishing for Food and Fodder: The Transnational Environmental History of Humboldt Current Fisheries in Peru and Chile since 1945 by Kristin Wintersteen Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Edward Balleisen ___________________________ Jocelyn Olcott ___________________________ Gunther Peck ___________________________ Thomas Rogers ___________________________ Peter Sigal Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Fishing for Food and Fodder: The Transnational Environmental History of Humboldt Current Fisheries in Peru and Chile since 1945 by Kristin Wintersteen Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Edward Balleisen ___________________________ Jocelyn Olcott ___________________________ Gunther Peck ___________________________ Thomas Rogers ___________________________ Peter Sigal An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Kristin Wintersteen 2011 Abstract This dissertation explores the history of industrial fisheries in the Humboldt Current marine ecosystem where workers, scientists, and entrepreneurs transformed Peru and Chile into two of the top five fishing nations after World War II. As fishmeal industrialists raided the oceans for proteins to nourish chickens, hogs, and farmed fish, the global “race for fish” was marked by the clash of humanitarian goals and business interests over whether the fish should be used to ameliorate malnutrition in the developing world or extracted and their nutrients exported as mass commodities, at greater profit, as a building block for the food chain in the global North. -

Building Ambitious Us Subnational Climate Initiatives: Embracing Dignity and the Tradition of Civic Engagement

BUILDING AMBITIOUS US SUBNATIONAL CLIMATE INITIATIVES: EMBRACING DIGNITY AND THE TRADITION OF CIVIC ENGAGEMENT A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Liberal Studies By Cyd Slayton, M.F.A Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 2018 Copyright 2018 by Cyd Slayton All Rights Reserved ii BUILDING AMBITIOUS US SUBNATIONAL CLIMATE INITIATIVES: EMBRACING DIGNITY AND THE TRADITION OF CIVIC ENGAGEMENT Cyd Slayton, M.F.A. DLS Chair: Thomas Kerch, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The human activity of emitting greenhouse gasses (GHGs) is contributing to the intensification of extreme weather, according to nearly all climate scientists. Already, atmospheric concentrations of the three most heat-trapping greenhouse gasses (GHGs)— carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—are “unprecedented for at least 800,000 years.”1 As a result, heat waves, droughts, floods, cyclones, wildfires, and rising seas are more frequent and powerful. While the planet will survive the climate catastrophes, a destabilized atmosphere threatens all species, including our own. Over the past 25 years, total GHG emissions have continued to rise, despite international and bilateral climate treaties. Generally, the US has refused to ratify treaties that appear to impinge on national sovereignty, including the Kyoto Protocol with its “top 1 IPCC Working Groups I, II and III, Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report , Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (Geneva: IPCC, 2014), 4, accessed March 2, 2018, https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment- report/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf. -

Everett Olson and Lila Richardson Baker Were Married in 1939 and Had Three Children, Claire (B

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES E V E R E T T C . O LSON 1910—1993 A Biographical Memoir by M ICH A E L A. B E L L Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1998 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. Photo by Ruth O. Hotton EVERETT C. OLSON November 6, 1910–November 27, 1993 BY MICHAEL A. BELL I don’t know how a person who is a historian of this sort [a paleontologist] can have any worry about death, . because you’re just part of a chain which has been going on for at least three and a half billion years. And things live and things die, . and when you do, it causes a mess tempo- rarily; a little whirl in your own society, but that’s all. And we are a single species; one of probably ten million species that exists on the earth today, and of countless millions that have existed in the past. And we’re a small segment in time; a transition from when we weren’t to when we won’t be, which . I hope isn’t as sudden as it might be.1 T THE TIME of this interview, Everett Claire Olson (Ole Ato his friends) had been retired for six years. He lived another eleven, during most of which he was vigorous and productive. When he died, there was more than “a little whirl.” Death did not cheat Ole; he had a long, fulfilling life. -

Bibliography

Bibliography ABAN, I.B., MEERSCHAERT, M.M. and PANORSKA, A.K. (2006). Parameter estimation for the truncated Pareto distribution. The American Statistician, 101, 270–277. ABBOTT, G.A. (1925). A chemical investigation of the water of Devil’s Lake, North Dakota. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Sciences, 34, 181–184. ABEL, N.H. (1826). Auflosung€ einer mechanischen Aufgabe [Resolution of a mechanical object]. Journal fur€ die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 1, 153–157. ABEL, N.H. (1881a). Solution de quelques problèmes à l’aide d’intégrales définies [Solution of some problems using definite integrals]. In: SYLOW, P.L.M. and LIE, S. (eds.). Oeuvres complètes de Niels Henrick Abel. Christiana, Grøndhal and Søn, 1, 11–27. ABEL, N.H. (1881b). Sur quelques intégrales définies [On some definite integrals]. In: SYLOW, P.L.M. and LIE, S. (eds.). Oeuvres complètes de Niels Henrick Abel. Christiana, Grøndhal and Søn, 1, 93–102. ABRAMOWITZ, M and STEGUN, I.A. (eds.) (1965). Handbook of mathematical functions with formulas, graphs, and mathematical tables. 2nd edn., New York, NY, Dover Publications. ABRAMS, M.J. (1978). Computer image processing – geologic applications. Publication 78-34, Pasadena, CA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. ABSAR, I. (1985). Applications of supercomputers in the petroleum industry. Simulation, 44, 247–251. ACHESON, C.H. (1963). Time-depth and velocity-depth relations in western Canada. Geophysics, 28, 894–909. ACKLEY, D.H., HINTON, G.E. and SEJNOWSKI, T.J. (1985). A learning algorithm for Boltzmann machines. Cognitive Science, 9, 147–169. ADAMATZKY, A. (ed.) (2010). Game of Life cellular automata. London, Springer-Verlag. ADAMOPOULOS, A. -

2020 CATALOG Chicago Journals

:: 2020 CATALOG chicago journals Founded in 1891, the University of Chicago Press is one of the oldest continuously operating university presses in the United States. From its inception, a primary goal of the Press has been to publish academic findings and analyses from scholars the world over. Journals publishing was integral to the founding of the Press: the Journal of Political Economy, its first scholarly publication, has been published here continuously for 125 years. In this time, the University of Chicago Press has proudly fostered partnerships with publications in diverse areas of study. Several of Chicago’s journals were the first of their kind in their respective fields. TheAmerican Journal of Sociology, founded in 1895, is the oldest journal devoted to sociology. Social Service Review was founded in 1927, just as the field of social work was being established. Until the publication of History of Religions in 1961, no journal had devoted itself exclusively to the subject of comparative religious history. The University of Chicago Press journals portfolio represents more than 80 scholarly publications that cover a wide range of disciplines, from the humanities and the social sciences to the life and physical sciences. In addition to working with departments and faculty of the University of Chicago, the University of Chicago Press publishes influential scholarly journals on behalf of learned and professional societies and associations, foundations, museums, and other not-for-profit organizations. All are peer-reviewed publications, with readerships that include scholars, scientists, and practitioners, as well as other interested, educated individuals. With its roots firmly in the academy, the University of Chicago Press Journals Division continues to recognize the importance of the dissemination of significant research. -

College of Science and Health Annual Report

College of Science and Health Annual Report 2014 DePaul University 2014 CSH Annual Report Table of Contents 02 Letter from the Dean 03 Contributors 04 College of Science and Health Leadership 05 Advisory Council 06 Enrollment 09 Chicago Connections 11 International Reach 12 Department of Biological Sciences 13 Department of Chemistry 14 Department of Environmental Science and Studies 15 DePaul’s Family and Community Services 16 Department of Health Sciences 17 Department of Mathematical Sciences 18 School of Nursing 19 Department of Physics 20 Department of Psychology 21 STEM Studies 22 Teaching Technology Innovations 24 Faculty Grants 26 Staff Achievements 27 Student Accomplishments 31 Student Spotlight: Dean’s Undergraduate Summer Research Fellow, Vishal Patel 32 Dr. Timothy Sparkes, Recipient of 2014 CSH Excellence in Teaching Award 33 Faculty Publications 54 Gratitude for Service: 2014 Retirees 2 A Letter from the Dean A Letter from Dean Gerald P. Koocher Last year brought many transitions and opportunities for the College of Science and Health (CSH). Our enrollments continued to grow substantially, we increased our laboratory capacity significantly, we said “good-bye” to many dedicated retiring faculty and staff members, and we began focusing on an updated strategic plan for the College. Our undergraduate population has held steady and graduate enrollments have grown, led by the expansion of our School of Nursing programs under the leadership of Professor William Cody. The Trustees validated our 2013 business plan, and authorized the build out of new laboratory space in McGowan South and Byrne Halls. With the skilled management of the DePaul facilities team and the expert leadership of Associate Dean Rick Niedziela, the space was completed and ready for occupancy in December, 2014. -

Scientific Journals As Fossil Traces of Sweeping Change in the Structure and Practice of Modern Geology

Page 1 of 24 Journal of Research Practice, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2008 Journal of Research Practice Volume 4, Issue 1, Article M1, 2008 Main Article: Scientific Journals as Fossil Traces of Sweeping Change in the Structure and Practice of Modern Geology Sarah E. Fratesi Department of Geology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, Florida, 33620, USA [email protected] H. L. Vacher Department of Geology, University of South Florida, 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, Florida, 33620, USA [email protected] Abstract In our attempts to track changes in geological practice over time and to isolate the source of these changes, we have found that they are largely connected with the germination of new geologic subdisciplines. We use keyword and title data from articles in 68 geology journals to track the changes in influence of each subdiscipline on geology over all. Geological research has shifted emphasis over the study period, moving away from economic geology and petroleum geology, towards physics- and chemistry- based topics. The Apollo lunar landings had as much influence on the topics and practice of geological research as the much-cited plate-tectonics revolution. These results reflect the barely-tangible effects of the changes in vocabulary and habit of thought that have pervaded the substance of geology. Geological literature has increased in volume and specialization, resulting in a highly fragmentary literature. However, we infer that “big science,” characterized by large amounts of funding, collaboration, and large logistical investments, makes use of this specialization and turns “twigging” into a phenomenon that enhances, rather than inhibits, the enterprise of research.