Stale Etldcs REFORM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 1 Hearing on Nomination of Attorney General Scott

1 HEARING ON NOMINATION OF ATTORNEY GENERAL SCOTT PRUITT TO BE ADMINISTRATOR OF THE U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY Wednesday, January 18, 2017 United States Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Washington, D.C. The committee met, pursuant to notice, at 10:00 a.m. in room 406, Dirksen Senate Office Building, the Honorable John Barrasso [chairman of the committee] presiding. Present: Senators Barrasso, Carper, Inhofe, Capito, Boozman, Wicker, Fischer, Moran, Rounds, Ernst, Sullivan, Cardin, Sanders, Whitehouse, Merkley, Gillibrand, Booker, Markey, Duckworth, and Harris. Also Present: Senator Lankford. 1 2 STATEMENT OF THE HONORABLE JOHN BARRASSO, A UNITED STATES SENATOR FROM THE STATE OF WYOMING Senator Barrasso. Good morning. I call this hearing to order. We have quite a full house today. I welcome the audience. This is a formal Senate hearing, and in order to allow the Committee to conduct its business, we will maintain decorum. That means if there are disorders, demonstrations by a member of the audience, the person causing the disruption will be escorted from the room by the Capitol Police. Since this is our first hearing of this session, I would like to welcome our new members, Senators Jerry Moran, Joni Ernst, Tammy Duckworth and Kamala Harris. Thank you very much and congratulations in joining the Committee. I would also like to welcome Senator Tom Carper in his new role as the Ranking Member of the Committee. You are here, even if you have a scratchy throat, 40 years from when you were Treasurer of Delaware, member of Congress, governor, member of the U.S. -

Amicus Curiae the Chickasaw Nation Counsel for Amicus Curiae the Choctaw Nation of FRANK S

No. 18-9526 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— JIMCY MCGIRT, Petitioner, v. STATE OF OKLAHOMA, Respondent. ———— On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Appeals of the State of Oklahoma ———— BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE TOM COLE, BRAD HENRY, GLENN COFFEE, MIKE TURPEN, NEAL MCCALEB, DANNY HILLIARD, MICHAEL STEELE, DANIEL BOREN, T.W. SHANNON, LISA JOHNSON BILLY, THE CHICKASAW NATION, AND THE CHOCTAW NATION OF OKLAHOMA IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ———— MICHAEL BURRAGE ROBERT H. HENRY WHITTEN BURRAGE Counsel of Record 512 N. Broadway Avenue ROBERT H. HENRY LAW FIRM Suite 300 512 N. Broadway Avenue Oklahoma City, OK 73102 Suite 230 Oklahoma City, OK 73102 (405) 516-7824 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae [Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover] February 11, 2020 WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 STEPHEN H. GREETHAM BRAD MALLETT Senior Counsel Associate General Counsel CHICKASAW NATION CHOCTAW NATION OF 2929 Lonnie Abbott Blvd. OKLAHOMA Ada, OK 74820 P.O. Box 1210 Durant, OK 74702 Counsel for Amicus Curiae the Chickasaw Nation Counsel for Amicus Curiae the Choctaw Nation of FRANK S. HOLLEMAN, IV Oklahoma DOUGLAS B. ENDRESON SONOSKY, CHAMBERS, SACHSE, ENDRESON & PERRY, LLP 1425 K St., NW Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 682-0240 Counsel for Amici Curiae the Chickasaw Nation and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................ ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ........................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................. 5 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 5 I. OKLAHOMA’S AND THE NATIONS’ NEGOTIATED APPROACH TO SET- TLING JURISDICTIONAL ISSUES ON THEIR RESERVATIONS BENEFITS ALL OKLAHOMANS .............................. -

Degrees of Progress, Spring 2017

Degrees of Progress News from the State Regents for Higher Education Volume 2, Issue 2 | Spring 2017 Invest in Higher Education Today Chancellor Glen D. Johnson, Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education The Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education While task force work is underway to shape higher recently announced formation of a task force to education tomorrow, our colleges and universities are consider ways to improve degree completion and struggling to serve students today in the wake of historic increase productivity through enhanced modernization, budget cuts. For FY17, cuts to public higher education efficiencies and innovation in higher education. The task exceeded $157 million, a 16.4 percent decrease from the force will examine academic models, online education, FY16 appropriation. With current appropriations below structure, fiscal services, operational efficiencies, 2001 levels, funding for public higher education has workforce development, and information technology been set back a full generation. Following these cuts, to ensure each facet of the system is designed to best the State Higher Education Executive Officers association serve Oklahoma students and meet workforce needs. has ranked Oklahoma last of the 50 states in the The fiscal viability of each institution will be reviewed in percentage change in state support for higher education the context of the budget cuts over the last several years. from FY16 to FY17. Oklahoma also ranks last among the We believe this will be the most important initiative in 33 participating Complete College America (CCA) states Oklahoma higher education in the last three decades. in state funding support from FY12 to FY17. Oklahoma’s future economic growth greatly depends Contents on a well-educated workforce. -

Member Guide What People Are Saying About Why They’Re Members of OK Ethics

The Oklahoma Business Ethics Consortium 2013 ® Member Guide What people are saying about why they’re members of OK Ethics: Adds value to work and life • Great people/friends; associate with the “best of the best” • Builds self-awareness • Helps relate to others’ situations • Keeps ethics in the forefront • Do good – build character and ethical culture • Curiosity • Need and relationship • Accountability • Shared values • Like-mindednesss • Learning • Oklahoma values • Interaction and connecting with others who have shared values and priorities • Top companies are leading • Positive examples • Excellent speakers • Genuinely incredible group of people with high level of integrity • Integrity of business leaders • Setting a standard • Diversity • Grassroots • No hidden agenda or sales pitch • Best practices • Relationships/accountability • Inspiration • Love our state – making it stronger • Increasing awareness in our business community • Something for everyone • It’s the right thing to do. Beginning Our Tenth Year of Celebrating Oklahoma Values Promoting Integrity at Work www.OKEthics.org ® The OK Ethics Story Who Knew? Certainly not the handful of people who started a small discussion group in the fall of 2003. That little group grew by word-of-mouth to nearly double attendance at every meeting for the first few months. The Oklahoma Business Ethics Consortium has grown to over 800 members representing more than 200 companies. And, this was all accomplished through the efforts of dedicated volunteers. What started in Oklahoma City as a grassroots effort, kicked into high gear during the summer of 2004, when business leaders and educators from Tulsa and Oklahoma City gathered for a strategic planning session in Stroud, Oklahoma. -

Oklahoma City Family-Owned for 50 Years • Sanitone Dry Cleaning • Complete Laundry Service • Wedding Gown Preservation • Households Oklahoma City 10805 N

b2.qxp 9/8/2014 4:23 PM Page 1 Oklahoma City FRIDAY, Friday, September 12, 2014, Page B-2 news Gill, Anoatubby named recipients of 2014 John F. Kennedy Awards Country music leg- end Vince Gill and Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatub- by will accept the John F. Kennedy Community Service Award at an event set for Oct. 28 in Oklahoma City. Service For Sight The event, which will be held at the THE OKC DELTA Gamma Alumnae Chapter officers met to discuss their Oklahoma City Golf philanthropic project “Service for Sight;” providing funds and services to those who are visually impaired or blind. They are supporting the local and Country Club, is non-profit, New View, this year as well as the Owl Camp for visually being hosted by the impaired children. Delta Gamma officers, left to right; Betsy Enos, Beth Knights of Columbus VINCE GILL GOV. BILL ANOATUBBY Ann Perry, (in the back), Suzanne Reynolds (front) Kristen Derryberry (in Council 1038. Proceeds the back), Jane Clark (front) Mario Vaughn, Pam Troup and Kay Lindsey. from the dinner support tinguished club of hon- for his contributions of the Santa Fe Family orees, and to celebrate time and talents for Life Center in its mis- the legacies they con- numerous causes in sion to provide recre- tinue to build in Okla- Oklahoma, his willing- ation and athletic pro- homa and beyond.” ness to participate in grams for disadvan- The John F. Kennedy the celebration of Okla- taged, disabled and award honors individu- homa’s history and for mentally challenged als making a significant providing comfort to children. -

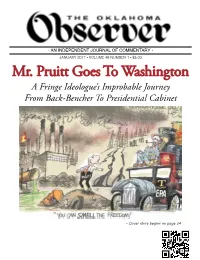

Mr. Pruitt Goes to Washington a Fringe Ideologue’S Improbable Journey from Back-Bencher to Presidential Cabinet

• An Independent JournAl of CommentAry • JANUARY 2017 • VOLUME 49 NUMBER 1 • $5.00 Mr. Pruitt Goes To Washington A Fringe Ideologue’s Improbable Journey From Back-Bencher To Presidential Cabinet – Cover story begins on page 24 Observations www.okobserver.net Welcome! VOLUME 49, NO. 1 With this, the first issue of our 49th year as Oklahoma’s premier jour- PUBLISHER Beverly Hamilton nal of free voices, The Observer welcomes nearly 200 new readers – EDITOR Arnold Hamilton many joining us thanks to the generosity of loyal subscribers who re- sponded to our annual holiday gift campaign. DIGITAL EDITOR MaryAnn Martin As way of introduction, you’ll soon discover The Observer is the antith- FOUNDING EDITOR Frosty Troy esis of the state’s lockstep, conservative mainstream media. While they shamelessly trumpet the interests of the deep-pocketed, silk-stocking ADVISORY BOARD 1%, we champion equality and fairness for all – regardless of race, gen- Marvin Chiles, Andrew Hamilton, der, religion, sexual preference or socio-economic status. Matthew Hamilton, Scott J. Hamilton, Trevor James, Ryan Kiesel, We are unabashed liberals, staunch supporters of public education, George Krumme, Gayla Machell, separation of church and state, and civil liberties. We believe that to- Bruce Prescott, Robyn Lemon Sellers, gether we have a moral obligation to take care of children in the dawn of Kyle Williams their lives and seniors in the twilight of theirs – everyone else is on their OUR MOTTO own, unless they need a hand-up, not a handout. To Comfort the Afflicted and Afflict the We don’t agree with every viewpoint we publish, but we believe few Comfortable. -

The University of Tulsa Magazine Is Published Three Times a Year Major National Scholarships

the university of TULSmagazinea 2001 spring NIT Champions! TU’s future is in the bag. Rediscover the joys of pudding cups, juice boxes, and sandwiches . and help TU in the process. In these times of tight budgets, it can be a challenge to find ways to support worthy causes. But here’s an idea: Why not brown bag it,and pass some of the savings on to TU? I Eating out can be an unexpected drain on your finances. By packing your lunch, you can save easy dollars, save commuting time and trouble, and maybe even eat healthier, too. (And, if you still have that childhood lunch pail, you can be amazingly cool again.) I Plus, when you share your savings with TU, you make a tremendous difference.Gifts to our Annual Fund support a wide variety of needs, from purchase of new equipment to maintenance of facilities. All of these are vital to our mission. I So please consider “brown bagging it for TU.” It could be the yummiest way everto support the University. I Watch the mail for more information. For more information on the TU Annual Fund, call (918) 631-2561, or mail your contribution to The University of Tulsa Annual Fund, 600 South College Avenue, Tulsa, OK 74104-3189. Or visit our secure donor page on the TU website: www.utulsa.edu/development/giving/. the university of TULSmagazinea features departments 16 A Poet’s Perspective 2 Editor’s Note 2001 By Deanna J. Harris 3 Campus Updates spring American poet and philosopher Robert Bly is one of the giants of 20th century literature. -

Business Litigation Editor: Mark Ramsey Contents March 15, 2014 • Vol

Volume 85 u No. 8 u March 15, 2014 ALSO INSIDE • Solo & Small Firm Conference • Legislative Update • OBA Day at the Capitol MEMBER BENEFIT Go. Travel discounts for OBA members Avis Car Rental Hertz Car Rental Reference code Discount number A674000 CDP 0164851 Avis toll-free Hertz toll-free 800-831-8000 800-654-3131 www.avis.com www.hertz.com Colcord Hotel Go Next Downtown Oklahoma City International Travel Group rates available $149/night Deluxe King, Deluxe Double Airfare from either Oklahoma City or $179/night Superior Corner King $279/night Colcord Suite Tulsa, accommodations, transfers, breakfast buet and other 866-781-3800 amenities included. Mention that you are an OBA member ZZZ*R1H[WFRP www.colcordhotel.com access code OKBR. )RUPRUHPHPEHUSHUNVYLVLWZZZRNEDURUJPHPEHUVPHPEHUVEHQHÀWV Vol. 85 — No. 8 — 3/15/2014 The Oklahoma Bar Journal 513 514 The Oklahoma Bar Journal Vol. 85 — No. 8 — 3/15/2014 Theme: Business Litigation Editor: Mark Ramsey contents March 15, 2014 • Vol. 85 • No. 8 pg. 588 OBA Day at the Capitol DEPARTMENTS 516 From the President 556 Editorial Calendar 588 From the Executive Director 589 Ethics/Professional Responsibility 591 Oklahoma Bar Foundation News 595 OBA Board of Governors Actions 597 Access to Justice 599 Young Lawyers Division 601 Calendar 603 For Your Information FEATURES 608 Bench and Bar Briefs 519 Concurrent ‘Alter-Ego’ Claims: 610 In Memoriam Oklahoma Leads the Nation in 612 What’s Online Extending Protection to 616 The Back Page Shareholders, Officers and Directors By John D. Stiner 527 But It’s Mine: The Signer Versus Joint Owner Problem with Bank Accounts By Brandee Hancock 531 The Court of Competent Jurisdiction: Is that Your Final Answer? By Spencer C. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 2017 No. 28 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, those impacted, with respect for the called to order by the Honorable MIKE PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, rule of law and the rights of State and ROUNDS, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, February 16, 2017. local governments. South Dakota. To the Senate: Pruitt has earned the support of Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, countless groups across the country, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby f appoint the Honorable MIKE ROUNDS, a Sen- from State environmental protection ator from the State of South Dakota, to per- officers to agricultural leaders. He has PRAYER form the duties of the Chair. the bipartisan backing of dozens of his The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- ORRIN G. HATCH, fellow attorneys general as well. They fered the following prayer: President pro tempore. say he is someone who is ‘‘committed Let us pray. Mr. ROUNDS thereupon assumed the to clean air and clean water,’’ one who Eternal Spirit, to whom we must give Chair as Acting President pro tempore. is apt to ‘‘come to Congress for a solu- an account for all our powers and privi- f tion, rather than inventing power’’ for leges, guide our steps, use us to bring himself. RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY healing to our Nation and world. -

Human Rights Activist Bob Lemon Remembered As an Oklahoma City

Print News for the Heart of our City. Volume 54, Issue 11 November 2016 Read us daily at www.city-sentinel.com Ten Cents Page 54 Page 9 Page 12 Advocates of SQ 780 and 781 launch TV ad campaign 31st annual Peace Festival Elvis Costello spins tales and serenades during solo concert Federal Election House District 94 Larry Joplin – Scott Inman YES (to retain in office) U.S. Senate P. Thomas Thornbrugh – James Lankford House District 97 YES (to retain in office) Oklahoma County Election Jason Lowe Oklahoma County Sheriff State Questions John Whetsel House District 99 George Young S.Q. 776 City-area Legislative Races (death penalty methods) – NO Greg Treat Judicial Retention Votes S.Q. 777 Senate District 47 (right to farm) – neutral State Supreme Court S.Q. 779 House District 82 James R. Winchester – (penny sales tax for common, Kevin Calvey YES (to retain in office) higher and careertech Douglas L. Combs – education) – neutral House District 83 YES (to retain in office) S.Q. 780 Randy McDaniel (sentencing reform) – YES Court of Criminal Appeals S.Q. 781 House District 85 Rob Hudson – (use of savings from Matt Jackson YES (to retain in office) sentencing reform – YES Carlene Clancy Smith S.Q. 790 Oklahoma City Public School school building maintenance (Technology updates, $54.4 House District 92 (to retain in office) (repeal of Section 5 ‘Blaine District Questions (Bonds including air conditioning, million bond) – YES Joe Griffin Amendment’ language) – YES totaling $180 million) safety and general Court of Civil Appeals S.Q. 792 equipment) – YES Proposition No. -

A Publication of the Oklahoma City Museum of Art | FY 2009-2010 OKLAHOMA CITY MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT a publication of the OKLAHOMA CITY MUSEUM OF ART | FY 2009-2010 OKLAHOMA CITY MUSEUM OF ART Annual Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2009, through June 30, 2010 Mission Enriching lives through the visual arts Vision Great art for everyone Purpose Creating a cultural legacy in art and education for current and future generations to experience at the Museum and carry with them throughout their lives Contents ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 Board of Trustees ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 6 President & CEO’s Summary ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Acquisitions, Loans & Deaccessions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Exhibitions & Installations ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 12 Film ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 14 Education & Public Programs ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 Volunteers ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Children & The

Volume 82 u No. 20 u August 6, 2011 ALSO INSIDE • Oklahoma Justice Commission • Board of Governors 2012 Vacancies Vol. 82 — No. 20 — 8/6/2011 The Oklahoma Bar Journal 1769 At the end of the day... Who’s Really Watching Your Firm’s 401(k)? And, what is it costing you? • Does your firm’s 401(k) include If you answered no to any of professional investment fiduciary these questions, contact the services? ABA Retirement Funds Program • Is your firm’s 401(k) subject to learn how to keep a close to quarterly reviews by an watch over your 401(k). independent board of directors? Phone: (800) 826-8901 • Does your firm’s 401(k) feature email: [email protected] no out-of-pocket fees? Web: www.abaretirement.com Who’s Watching Your Firm’s 401(k)? The American Bar Association Members/Northern Trust Collective Trust (the “Collective Trust”) has filed a registration statement (including the prospectus therein (the “Prospectus”)) with the Securities and Exchange Commission for the offering of Units representing pro rata beneficial interests in the collective investment funds established under the Collective Trust. The Collective Trust is a retirement program sponsored by the ABA Retirement Funds in which lawyers and law firms who are members or associates of the American Bar Association, most state and local bar associations and their employees and employees of certain organizations related to the practice of law are eligible to participate. Copies of the Prospectus may be obtained by calling (800) 826-8901, by visiting the website of the ABA Retirement Funds Program at www.abaretirement.com or by writing to ABA Retirement Funds, P.O.