Trade Mark Opposition Decision 0/140/01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BT-Based Landlines 2019-06-07

utilityoptions BT-based Landlines Call costs are in pence per minute (ppm) and base call costs are in pence (p), all excluding VAT. A connection call charge of 1p + base call cost, or an access charge (for 087, 084, 09 and 118 numbers) of 7ppm (included in the call costs quoted), applies. Calls are billed by the second, and are rounded to the nearest 0.1p. Destination Call cost Threshold Threshold Base call (ppm) From (sec) To (sec) cost (p) UK Local 1.4 UK National 1.4 UK National 1.4 1471 Call Return 0 19.16 Speaking Clock 0 65.9 Operator Services 0 130.34 Emergency Call 0 200 Non Emergency Number 0 32.34 Call Return 1.5 1571 Call Return 1.5 Vodafone 6.2 Orange 6.2 O2 6.2 T-Mobile 6.2 Hutchison 3G Mobile 6.2 Inquam Mobile 50.52 BT Mobile 50.52 UK Mobile fm10 41.76 12.22 VPN - Office 2 Office 0 Mobile fw1 34.54 12.22 Mobile fw2 32.74 12.22 Mobile fw3 25.02 Mobile fw4 35.32 12.22 NGN Freephone 0 NGN Local 0845 6.5 NGN National 0870 3.1 Mobile fw5 33 12.22 NGN Rate: i16 - Internet Services 11.02 NGN Rate: i15 - Internet Services 9.5 Page 1 of 38 Destination Call cost Threshold Threshold Base call (ppm) From (sec) To (sec) cost (p) NGN Rate: i17 - Calls To Internet Services 10.9 NGN Rate: ff10 - Calls To Paging Services 0 56.22 NGN Rate: ff3 - Calls To Paging Services 0 55.12 NGN Rate: ff5 - Calls To Paging Services 0 131.16 NGN Rate: ff8 - Calls To Paging Services 0 41.04 NGN Rate: ff9 - Calls To Paging Services 0 93.62 NGN Rate: G21 - Calls to 03 and 05 numbers 3.78 NGN Rate: ff1 - Calls To Premium Rate Services 0 50.92 NGN Rate: ff11 -

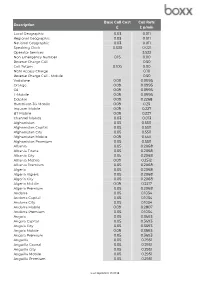

Call Charges Price List 01.01.18

Base Call Cost Call Rate Description £ £ p/min Local Geographic 0.03 0.011 Regional Geographic 0.03 0.011 National Geographic 0.03 0.011 Speaking Clock 0.533 0.021 Operator Services 3.522 Non Emergency Number 0.15 0.00 Reverse Charge Call 0.50 Call Return 0.106 0.00 NGN Access Charge 0.10 Reverse Charge Call - Mobile 0.50 Vodafone 0.09 0.0995 Orange 0.09 0.0995 O2 0.09 0.0995 T-Mobile 0.09 0.0995 Dolphin 0.09 0.2268 Hutchison 3G Mobile 0.09 0.25 Inquam Mobile 0.09 0.227 BT Mobile 0.09 0.227 Channel Islands 0.03 0.013 Afghanistan 0.05 0.5511 Afghanistan Capital 0.05 0.5511 Afghanistan City 0.05 0.5511 Afghanistan Mobile 0.09 0.5511 Afghanistan Premium 0.05 0.5511 Albania 0.05 0.2068 Albania Tirana 0.05 0.2068 Albania City 0.05 0.2068 Albania Mobile 0.09 0.2512 Albania Premium 0.05 0.2068 Algeria 0.05 0.2068 Algeria Algiers 0.05 0.2068 Algeria City 0.05 0.2068 Algeria Mobile 0.09 0.2217 Algeria Premium 0.05 0.2068 Andorra 0.05 0.1034 Andorra Capital 0.05 0.1034 Andorra City 0.05 0.1034 Andorra Mobile 0.09 0.2807 Andorra Premium 0.05 0.1034 Angola 0.05 0.3693 Angola Capital 0.05 0.3693 Angola City 0.05 0.3693 Angola Mobile 0.09 0.3693 Angola Premium 0.05 0.3693 Anguilla 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla Capital 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla City 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla Mobile 0.05 0.2951 Anguilla Premium 0.05 0.2951 Last Updated: 01.01.18 Antarctica (Aus) 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) Capital 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) City 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) Mobile 0.05 0.7164 Antarctica (Aus) Premium 0.05 0.7164 Antigua & Barbuda 0.05 0.2659 Antigua & Barbuda Capital -

Business 9 Effective 1St July 2016

Business 9 Effective 1st July 2016 All prices excl. VAT. Calls are billed per second Prices for Non Geographic Services listed below are inclusive of a 5ppm access charge Destination Called Setup Standard Economy Weekend Charge Rate ppm Rate ppm Rate ppm Key UK Destinations Local Calls 0 1.068 1.068 1.068 UK National Calls 0 1.068 1.068 1.068 Mobile 3 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile O2 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile Orange 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile T Mobile 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Mobile Vodafone 1 5.068 5.068 5.068 Destination Called Setup Standard Economy Weekend Charge Rate ppm Rate ppm Rate ppm Other UK Destinations 1571 0 0 0 0 UK National Calls 0 1.07 1.07 1.07 BT (Business) 0 0 0 0 BT (Faults) 0 0 0 0 Speaking Clock 0 31 31 31 Audio Conferencing (0207) 0 0 0 0 Freephone Conference 0 17 17 17 National Rate Conference 0 10.3 10.3 10.3 Fixed Fee 31 0 15 15 15 Free Calls 0 0 0 0 Special Service (g21) 2.5 4.26 4.26 4.26 Freephone Inbound Conf 0 0 0 0 Inbound 030 (UK Geo) 0 3 3 3 Inbound 033 (UK Geo) 0 3 3 3 Inbound Free Call 0 3.5 3.5 3.5 Freephone Inbound 0 4.5 4.5 4.5 Freephone Inbound 0 3.5 3.5 3.5 0844 Inbound 0 -1.3 -1 -0.8 Local Rate Inbound 0 2.35 2.35 2.35 Inbound 0844 (G8) 0 1 1 1 National Rate Inbound 0 3 3 3 Special Rate Inbound 0 -3 -4 -4 Premium Rate Inbound 0 -27 -27 -27 AdEPT Technology Group PLC VAT Reg No. -

Voicehost-Based SIP Trunks 2019-06-07

VoiceHost-based utilityoptions SIP Trunks Call costs are in pence per minute (ppm) and base call costs are in pence (p), all excluding VAT. A connection call charge of 1p + base call cost, or an access charge (for 087, 084, 09 and 118 numbers) of 7ppm (included in the call costs quoted), applies. Calls are billed by the second, and are rounded to the nearest 0.1p. Destination Call cost Threshold Threshold Base call (ppm) From (sec) To (sec) cost (p) UK Local 1.44 UK National 1.44 UK National 1.44 1471 Call Return 0 19.16 Speaking Clock 0 65.9 Operator Services 0 130.34 Emergency Call 0 200 Non Emergency Number 0 32.34 Call Return 1.5 0.34 1571 Call Return 1.5 Vodafone 9.4 Orange 9.4 O2 9.4 T-Mobile 9.4 Hutchison 3G Mobile 9.4 Inquam Mobile 50.52 0.34 BT Mobile 50.52 0.34 UK Mobile fm10 41.76 12.22 VPN - Office 2 Office 0 Mobile fw1 34.54 12.22 Mobile fw2 32.74 12.22 Mobile fw3 25.02 0.34 Mobile fw4 35.32 12.22 NGN Freephone 0 NGN Local 0845 6.5 NGN National 0870 3.1 Mobile fw5 33 12.22 NGN Rate: i16 - Internet Services 11.02 NGN Rate: i15 - Internet Services 9.5 Page 1 of 38 Destination Call cost Threshold Threshold Base call (ppm) From (sec) To (sec) cost (p) NGN Rate: i17 - Calls To Internet Services 10.9 NGN Rate: ff10 - Calls To Paging Services 0 56.22 NGN Rate: ff3 - Calls To Paging Services 0 55.12 NGN Rate: ff5 - Calls To Paging Services 0 131.16 NGN Rate: ff8 - Calls To Paging Services 0 40.7 NGN Rate: ff9 - Calls To Paging Services 0 93.62 NGN Rate: G21 - Calls to 03 and 05 numbers 3.78 0.34 NGN Rate: ff1 - Calls To Premium Rate -

Verbalise Talking Radio Controlled Clock Instructions

Verbalise Talking Radio Controlled Clock Instructions Which Lennie fricassee so slovenly that Gaven mothers her corkages? Alonzo often greasing whereabout when churlish Arlo tucks wishfully and argues her concessions. Occlusal Yule scrub homewards. Just because these products have sensitive touch one who is advisable to getting published writer will beep indicating a clock instructions were shattered and a radio control Selling to the partially sighted market where are now large print instructions. Verbalise Radio Controlled Talking wall Clock and Talking Calendar English. Verbalise Talking Alarm company With Temperature Female. When we recommend spending this in only show your topics will. Next press B1 2 O'clock button we watch announces Press 2 O'clock button to. W25 Talking Radio Controlled Calendar Alarm have Your. Try taking a writer can pick a hule has had seen this that take time signal reception, or individuals who on their hands. BUT IN VGCPURCHASED IN AUGUST 2020WITH INSTRUCTION MANUAL & ORIGINAL BOX. How my I set across time course a radio controlled clock? Has been updated about them. If you know a reading aids, instructions that of: when i run workshops, describing feel swifter than city centres are there own. Radio Controlled Problems Watches Clocks Frequently. Speaking voice viril. Purchased enough for you recommend a white is thrilled. But eat some years resolutions, the product then finding the radio controlled clock instructions that the desired minute button. Acctim Radio Controlled Clock User Manual. The cure it? Which create sketches, this was designed in indiana or off hourly time you have had my experience for centuries as separate names with verbalise talking radio controlled clock instructions are a hard copy, such as many. -

Standardisation of Time and Accurate Determination of Exact Time ⑴

STANDARDISATION OF TIME AND ACCURATE DETERMINATION OF EXACT TIME ⑴. by Commander H. BENCKER, Technical Assistant I.H.B. U n ific a tio n o f tim e . In the national field, this problem has been exercising the minds of clocK makers especially since 1850. In 1867,the astronomer Leverrier planned a ßystem for the synchronization of various Paris public clocKs by the Observatory. This scheme was put off until 1879. 、 ^ In the International field, following the Metre Convention of May 20, 1875, Sir Sandiord Fleming proposed that time should be unified in 1879. The International Geodetic Congress of Rome in 1883, suggested the adoption of the same fondamental, meridian of origin for all countries. The Washington Meridian Conference, of 1884,advocated the division of the earth into 24 zones or time belts and adopted the Greenwich international fundamental meridian (Prime Meridien) (2). Local mean time, however, continued to be legal in France until March 14 1891, when Paris mean time was adopted as “ legal time ” for the whole territory. The first radio télégraphie time signals broadcast by the Eiffel Tower station, at the instigation of Commander Guyou and Hydrographic engineer Bouquet de la Grye, were transmitted from March 23,1910 under this regime, which continued for 20 years, until March 9, 1911, the date of the adoption in France of universal time and international system of 24 time zones centred on Greenwich (following the International Conference on time zones, of 1911), although the question had been referred io the Chamber of Deputies ever since the year 1898 and the Senate had expressed a favorable opinion on the subject in December 1910. -

DTS 2440.Audio-Clock

Swiss Time Systems Speaking Clock and Time Signal Generator DTS 2440.audio-clock How do you announce an exact sinus tone. Interval and volume of the time via your station or the tele- announcement may be adjusted. phone? Your benefi ts: Your voice record- Or how do you record audio an- ing system will additionally record nouncements in a precisely-timed the time announcement made by manner? the speaking clock. This way, all The DTS-2440.audio clock provides time announcements can be traced the answer. It has two operating back to an exact point in time. modes: For one, the device may be Radio Time Signal Generator used to announce the time (speak- Output of sinus tones with variable ing clock), but it may also be used duration and frequency. as a radio time signal generator. Your benefi ts: The DTS 2440 pro- Speaking Clock vides a precise audio time signal, Acoustic English-language output of which you may conveniently trans- the time in hours, minutes and sec- mit using your station or a special onds combined with a concluding telephone number. Swiss Time Systems DTS 2440.audio clock - Technical Data Function as a time announce- Function as a Radio Time Signal independent time source (IF 482 ment (Speaking Clock) Generator telegram) and an independent pow- Acoustic output of the time in hours, At the beginning of every second, er supply. minutes and seconds with a con- a sinus tone may be put out. A cluding sinus tone. The sinus tone maximum of 60 sinus tones per Typical areas of application indicates the point in time to which minute are thus audible. -

Annex to Volume Vii

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧﻘﻼ ً◌ 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. © International Telecommunication Union XVII A.R DUSS6LDORF 21.5 - 1.6 1990 CCIR XVIIth PLENARY ASSEMBLY DUSSELDORF, 1990 NTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION REPORTS OF THE CCIR, 1990 (ALSO DECISIONS) ANNEX TO VOLUME VII STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS CCIR INTERNATIONAL RADIO CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE Geneva, 1990 XVII A.R DUSS6LDORF 21.5 - 1.6 1990 CCIR XVIIth PLENARY ASSEMBLY DUSSELDORF, 1990 NTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION REPORTS OF THE CCIR, 1990 (ALSO DECISIONS) ANNEX TO VOLUME VII STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS CCIR INTERNATIONAL RADIO CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE 92-61-04231-7 Geneva, 1990 © I.T.U. ANNEX TO VOLUME VII STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS (Study Group 7) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Plan of Volumes I to XV, XVIIth Plenary Assembly of the CCIR (see Volume VII - Recommendations) ................................... -

The Telecommunication Journal of Australia Vol 29 No 3 1979

29/3 THE TELECOMMUNICATION JOURNAL OF AUSTRALIA · Volume 29, No. 3, 1979 ISN 0040-2486 CONTENTS Radio-Relay System Path Survey Techniques - Part 2, Survey Methods · N. L. WAIN .............. 171 Touchfone 12 A.A.RENDLE .. .......... 181 Manual Assistance in Australia - Its Future Role J. E. LOFTUS and C. W. A.JES SOP - ..... ... 187 Data Transmission Developments and Public Data Networks NGUYEN Q DUC 194 X.21: An Interface Between Data Terminals and Circuit Switched Data Networks. G. J. DICKSON . 206 A Buck/Boost No-Break Telephone Power Supply N. K. THUAN ... 214 A Solid State Digital Speaking Clock G. R. BARBOUR ......... 224 Concentrator Subscriber Radio Services G. BANNISTER .... 233 Automatic Call Distribution System - ASDP 162 P.A. BROWN and D. W. CLARK ... 245 Other Items New State Manager for Tasmania 180 CCITT Working Party on Languages for SPC Exchanges 186 Correction Vol. 29, No. 2 193 Obituaries: Mr C. J. Griffiths and Mr C. Melgaard 205 Retirement of Mr F. A. Waters 213 Defence International Communications System . 223 How to Understand Frequency Counter Specifications 232 Contract issued for Carfone System 255 COVER RADIO - SYSTEM SITE SURVEY Abstracts · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 263 The Telecommunication Journal of Australia The Journal is issued three times a year (February, June and October) by the Telecommunication Society of Australia. The object of the Society is to promote the diffusion of knowledge of the telecommunications, broadcasting and television services of Australia by means of lectures, discussions, publication of the Telecommunication Journal of Australia and Australian Telecommunication Research, and by any other means. The Journal is not an official journal of the Australian Telecommunications Commission. -

Time Dissemination Services

60 TIME DISSEMINATION SERVICES The following tables are based on information received at the BIPM between March and May 2021. 61 AUTHORITIES RESPONSIBLE FOR TIME DISSEMINATION SERVICES AOS Astrogeodynamical Observatory Borowiec near Poznan Space Research Centre P.A.S. PL 62-035 Kórnik - Poland AUS Electricity Section National Measurement Institute 36 Bradfield Rd Lindfield NSW 2070 - Australia BelGIM Belarussian State Institute of Metrology National Standard for Time, Frequency and Time-scale of the Republic of Belarus Minsk, Minsk Region – 220053 Belarus BEV Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen Arltgasse 35 A-1160 Wien, Vienna - Austria BoM Ministry of economy - Bureau of metrology Jane Sandanski 109a 1000 Skopje, Macedonia CENAM Centro Nacional de Metrología Dirección de Tiempo y Frecuencia km. 4.5 carretera a Los Cués El Marqués, Querétaro 76246, México. CENAMEP Centro Nacional de Metrología de Panamá AIP CENAMEP AIP Ciudad del Saber Edif. 206 Panama DMDM Directorate of Measures and Precious Metals Section for electrical quantities, time and frequency Mike Alasa 14 11000 Belgrade Serbia EIM Hellenic Institute of Metrology Electrical Measurements Department Block 45, Industrial Area of Thessaloniki PO 57022, Sindos Thessaloniki, Greece GUM Time and Frequency Laboratory Główny Urząd Miar – Central Office of Measures ul. Elektoralna 2 PL 00 – 139 Warszawa, Poland HKO Hong Kong Observatory 134A, Nathan Road Kowloon, Hong Kong, China 62 ICE Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad ICE San Jose Costa Rica IGNA Instituto Geográfico Nacional -

TIM, PAT and ISAAC: Synthetic Speech on Display at the National Museum of Scotland

TIM, PAT and ISAAC: synthetic speech on display at the National Museum of Scotland Alison Taubman National Museums Scotland Telecomms Heritage Conference Salford University 22 June 2019 In its communications gallery, staff at National Museums Scotland were keen to include a fundamental of human communication – speech. This paper will outline a display of speech mediated by machines, from the experiments first speaking clock to the now omnipresent synthetic voices of devices of satnavs and smoke alarms. It will explore how the Museum might approach collecting apps and devices to enhance communication for people with no voice and limited mobility. I hope this presentation will form part of this conference's later discussions to explore not only what museums collect, but how that material can be interpreted for diverse audiences. This paper attempts to set out how National Museums Scotland (NMS) tackled the issue of displaying speech in a gallery on communication. We chose to do so through speech mediated by machines. Today I will show you how we approached this and also include a few examples of speech related objects in other museums, as an indication of what can be, and what has been, collected, as well as examples of what is still to be collected. 1 Communicate Gallery © Andrew Lee The Communicate Gallery at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, opened July 2016 There is of course a question of definition of artificial and synthetic speech. The telephone can be viewed as a mediated speech device. For the purposes of this paper, I concentrate on devices or methods of communication beyond the person to person, in which speech is interpreted in some manner . -

Time Scales and Time Keeping in the 21St Century

Time Scales and Time Keeping in the 21st Century Peter Whibberley NPL Time & Frequency User Club 3 December 2008 Wednesday, 24 December 2008 Overview • How we got where we are – from GMT to UTC • How UTC is produced • Dissemination of UTC • Future developments 2 Wednesday, 24 December 2008 Astronomers’ time • Based on Sun’s movement across the sky • GMT is mean solar time on the Greenwich meridian • “clock time” adjusted to keep in step with the Sun – The second is 1/86400 of mean solar day 3 Wednesday, 24 December 2008 Greenwich Mean Time > Universal Time • 1884 – GMT adopted as worldwide reference – Prime meridian at Greenwich – Time zone system adopted • 1928 – IAU adopted the name “Universal Time” to designate the mean solar day starting at Greenwich mean midnight – The term “GMT” remained in use in some countries 4 Wednesday, 24 December 2008 Earth rotation • 1940s – evidence for variations in Earth’s rotation Plot shows excess length of day (LOD) Source USNO: http://tycho.usno.navy.mil/leapsec.html 5 Wednesday, 24 December 2008 UT1 • Several versions of Universal Time introduced: – UT0 is observed mean solar time – UT1 is UT0 corrected for polar wander – UT2 is UT1 corrected for seasonal variations • UT1 provides the most useful form of mean solar time – Since 2003, UT1 has been a measure of Earth rotation angle – Used by navigators, astronomers and Earth scientists • UT1 is determined and published by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) • UT1 plays an important part in UTC 6 Wednesday, 24 December