Stonewatch 2001 Stonewatch the World of Petroglyphs Special 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnassarie Farm Archaeological Walkover Survey Dalriada Project

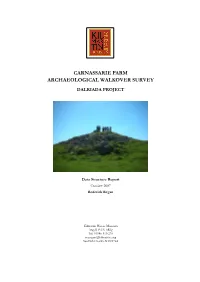

CARNASSARIE FARM ARCHAEOLOGICAL WALKOVER SURVEY DALRIADA PROJECT Data Structure Report October 2007 Roderick Regan Kilmartin House Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 [email protected] Scottish Charity SC022744 Summary The fieldwork at Carnassarie Farm has recorded over 240 sites, many of which were previously unknown. This has enhanced previous work, as well as substantially increasing our knowledge of past land-use in this northern area of Kilmartin Glen. The discovery of probable burial monuments and cup-marked rock panels adds an upland dimension to the story of prehistoric activity in Kilmartin Glen. The presence of a saddle quern and the recovery of a worked piece of quartz perhaps indicates early occupation on the slopes around Carnassarie and is intriguing since much of the archaeological record for this period has a ritual or burial focus. Aside from the Prehistoric period, this work has also highlighted the presence of fairly extensive, but dispersed settlement on the eastern slopes of Sron an Tighe Dhuibh. It is not known when this settlement was last inhabited, although it was certainly abandoned prior to the compilation of the 1 st Edition Ordnance Survey in 1873. The size and form of some of the larger rectangular structures perhaps indicates a Post Medieval date, although other structures may be earlier in origin. The survey has also shown that the head dyke to the west of the township of Carnassarie Mor, strictly delineated activities on either side. The eastern and internal area was given over to rig and furrow cultivation. To the west on Cnoc Creach little settlement or cultivation evidence was found, thus this area has been interpreted as pasture. -

PS Signpost Ballymeanoch

Ballymeanoch henge Signposts to Prehistory Location: Ballymeanoch henge (NR 833 962), barrow (NR835 963), standing stones and kerbed cairn (both NR 833 964) all lie at the southern end of the Kilmartin Valley in Argyll, Scotland. Main period: Neolithic and Bronze Age Access & ownership: All the monuments can be accessed from a car park 2.6 km south of Kilmartin, signposted ‘Dunchraigaig cairn’. A management agreement is in place between Historic Scotland and the landowner, enabling free public access. An interpretation panel can be found in the car park. This group of monuments at Ballymeanoch (Fig. 1) is part of an extensive ritual prehistoric landscape in the Kilmartin Valley. This stretches from Ormaig in the N to Achnabreck in the S, and includes various types of cairns, henges, standing stones, a stone circle, and many examples of rock art. Ballymeanoch henge is the only such monument in the west of Scotland. Built around 3000–2500 BC, it has an outer bank of 40 m diameter with an internal ditch, broken by entrance causeways at the N and S. The bank now rises to only 0.4 m; the flat-bottomed ditch is 4 m across and around 0.4 m deep. Fig. 1. Plan showing henge, standing stones, kerbed cairn and barrow. Drawn by K. Sharpe Canon Greenwell excavated the site in 1864, and found two burial cists in the centre, still visible. The largest had unusually long side slabs (up to 2.75 m) and is still covered with a massive capstone.The floor of the large cist was lined with small round pebbles but nothing was found inside. -

Parte a Nombre DNI Núm. Id Investig A.1. Sit Organis Dpto. / C Direcció Teléfon Categor Espec. Palabra A.2. Fo Li Lic. Filo D

Fecha del CVA 2020 Parte A. DATOS PERSONALES Nombre y Apellidos ARTURO RUIZ RODRIGUEZ DNI Edad Núm. identificación del Researcher ID investiggador Scopus Author ID Código ORCID A.1. Situación profesional actual Organismo Universidad de Jaén Dpto. / Centro Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Arqueoología Iberica Dirección Edif. C6 Campus Las Lagunillas CP 23071 Jaén España Teléfono 683750016 Correo electrónico arruiz ujaen.es Categoría profesional Catedrático Universidad. Area Prehistoria Fecha inicio 1991 Espec. cód. UNESCO Palabras clave A.2. Formación académica (título, institución, fecha) Liicenciatura/Grado/Doctorado Universidad Año Lic. Filosofía y Letras. Geografía e Historia Univ. Granada 1973 Doctor Historia Univ. Granada 1978 A.3. Indicadores generales de calidad de la producción científica -Seis Tramos de Investigación. El último concedido en 2010. -Tesis dirigidas: 13. La ultima en 2019 - Publicaciones en Congresos, Revistas y Editoriales de primer nivel: Ostraka (Perugia), EPOCH Publication, Archivo Español de Arqueología (Madrid), Roman Frontiers Studies, Oxbow Books (Oxford), Routledge studies in archaeology (New York) Quasar(Roma), Hermann (Paris), Bretschneider (Roma), Madrider Mitteilungen (Mainz) Cambridge University Press. Papers of the EAA, Barker and Lloyd, British School at Rome, Studia Celtica (Wales), Complutum, Antiquity, Quaternary Internaational, etc Parte B. RESUMEN LIBRE DEL CURRÍCCULUM Desde 1974 trabajo en el estudio del territorio ibero en el Alto valle del rio Guadalquivir (SE de la Península Ibérica) en el análisis del poblamiento y su desarrollo en función de las formas políticas que formula la aristocracia desde el s. VII al I a.n.e. En ese marco el proyecto de trabajo ha analizado la cconstrucción de los linajes gentilicios clientelares y su evolución hacia formas de dependencia aristocratica y su relación con la aparición del oppidum. -

Nether Largie South Cairn

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC098 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13299) Taken into State care: 1932 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2018 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE NETHER LARGIE SOUTH CAIRN We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE NETHER LARGIE SOUTH CAIRN CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Evidential values 11 2.3 Historical values 12 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 13 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 13 2.6 Natural heritage values 14 2.7 Contemporary/use values 14 3 Major gaps in understanding 15 4 Associated properties 17 5 Keywords 17 Bibliography 17 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. -

CMS 2018 4Th Qtr (Pdf)

Remember Those From Whom You Came Newsletter Of The Clan MacAlpine Society The Worldwide Organization For MacAlpines 4th Quarter 2018 ~ Volume 42 Commander’s News Nollaig Chridheil, Merry Christmas, haud Hogmany and a Guid New Year to you. Hogmanay, virtually unknown other than in Scotland, and generally called New Years Eve everywhere else, is an opportunity to greet friends and neighbors perhaps with a “handsel’ (a gift given by the hand). Often these gifts were symbolic wishes for the New Year to come. Coal for heat, whisky for good cheer and hospitality, while shortbread and black bun, a rich cake, symbolized good food all year. It has been a good year for our kindred, with exciting events in Scotland, the US and Canada. My thanks to the many whom I had the privilege of meeting at various events in, Illinois, Washington, Oregon, North Carolina, Georgia and of course Scotland over the last year. We continue to expand our knowledge of our past, of where and how we lived. I think that is a keen focus of all of us who honor and value the rich heritage of Scotland and each additional discovery that is made adds depth and texture to our understanding. January 25th will be the 259th anniversary of the birth of Robert Burns. It is a grand reason to put on the MacAlpine tartan and go out and celebrate. If you have never been to one of the highland games, they are all fun events; the MacAlpines host a hospitality tent at many of them. Next year we will be adding two new venues to our growing list. -

Kilmartin Museum PDF 3 MB

Kilmartin Glen is an internationally important archaeological landscape of world heritage status potential Mid Argyll has a greater biodiversity than anywhere in Scotland Some of the most important Prehistoric archaeological objects in Scotland have been found in Kilmartin Glen skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnkskldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\nd klndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngvkln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnk skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vklnUpper\vklns\vkln\ dfnkLargie Assemblage skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnk skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnk skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnk skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnk skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv kln\vkln\vklns\vkln\dfnk skldfhSK:LDJFhkajfhnak:fjnA:KLFJhnsdfk;jnsdk;fjsndcfjklsndfklcjsdnfkl;sjdbnflsdkfnsdfklnsdkl\ndklndl;nks\dlgvk\ngvklngv -

W Dolinie Łupawskich Megalitów

W dolinie łupawskich megalitów Megaliths Na środkowym Pomorzu, w ostępach leśnych nad rzeką Łupawą przetrwały of the Łupawa Valley wielkie kamienne grobowce sprzed ponad 5000 lat. Kto je wzniósł? Jakie tajemnice ukrywają? Zagubione w leśnej głuszy, PRZEWODNIK GUIDE czekają na swoich odkrywców. In central Pomerania, in the backwoods by Łupawa River, mighty stone tombs from over 5000 years ago have been preserved. Who made them? What secrets do they keep? Lost among dense forest, they await their explorers. Gmina Potęgowo Dolina Łupawskich Megalitów Autorka logotypu: Karolina Gołębiowska Europejski Szlak Megalitów – Polska Anglia: Szkocja: Francja: Niemcy: Polska: 1. Stonehenge (Anglia, Salisbury) - 23. Maes Howe(Srkocja, Orkady) - tolos 31. Jaskinia Czarownic (ArIes, Fontvieil- 43. Wilsen (Meklemburgia) - kopiec krąg kamienny 24. Callanish (Szkocja, Hybrydy) - krąg le) - grobowce z dolmenami Runowo – XVIII-wieczny pałac „Bocianie 2. Averbury (Angha, Wiltshire) - kromlech kamienny i aIeja menhirów 32. Dissignac Tumulus (Loire-Atlantique, 44. Klecken (Dolna Saksonia) - grobowiec Gmina Potęgowo Gniazdo”. Obecnie ośrodek wypoczynkowy 3. Silbury Hill (Anglia, Wiltshire) - 25. Clach an Trushal (Szkocja) Saint-Nazaire) - tumulus trapezowaty (kolonie indiańskie, traperskie, obozy kopiec - najwyższy menhir w Szkocji 33. Barnenez (Bretania) - karn 45. Sachsenwald - grobowce bezkomoro- zaprasza do odkrywania jeździeckie - jazda konna, plenery rzeźbiarsko 4. Cairhholy (Anglia, Kircudbright) - Na europejskim 26. Easter Aquhorthies (Szkocja) - krąg 34. La Grotte Aux Fees (Indre-et-Loire) we - hipotetyczna kolebka budowni- – malarskie itp.) Tel. 598115149 grobowiec kamienny - dolmen czych megalitów z Doliny Łupawy megalitów, pałaców, starych 5. Giant’s Hill (Anglia, Skendleby) - szlaku 27. Ring of Brotdgar (Szkoicja, Orkady) 35. Gavrinis (Bretania) - karn 46. Everstorfer Forst k. Barendorf (Me- grobowiec - krąg kamienny - wpisany na listę 36. -

The Children of Dunadd a Story for Children This Is the Story of Two

The Children of Dunadd A story for children This is the story of two children who lived at a place called Dunadd, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Dál Riata. Dunadd is situated at the southern end of Kilmartin Glen and if you were to journey to Kilmartin glen, you would find some of the most important monuments in Scotland which date back to very ancient times. The children’s story takes place at a time when Chiefs and Kings ruled in Argyll over one thousand and five hundred years ago. This was the home of the Scotti, the people who gave Scotland its name. There was once a boy called Fergus who was tall and strong and he could be very funny; he was always laughing and he was very clever, always learning new things every day because he knew that one day he would become the leader of his tribe, just like his father. There is so much to tell you about Fergus that I think I will let Fergus tell you his story........... My name is Fergus and I am 8 years old and I have a little sister called Mhairi who is 5 years old. We stay at a place called Dunadd with our mum and dad in a house built on the very top of Dunadd hill (hill fort). Mhairi and I love to stand at the top of the hill and look out across the moor (Moine Mhòr) and in the distance we can see the mountains of the Island of Jura and the sea lochs and we can also look out into the distance towards the glen and see the place where our ancestors built many special stone cairns. -

Maquetación 1

Las piedras de la memoria (II). El uso en época romana de espacios y monumentos sagrados prehistóricos del Sur de la Península Ibérica Stones of memory (II). The use in Roman times of prehistoric sacred spaces and monuments of Southern Iberia Leonardo GARCÍA SANJUÁN*, Pablo GARRIDO GONZÁLEZ*, Fernando LOZANO GÓMEZ** Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología (*). Departamento de Historia Antigua (**). Universidad de Sevilla [email protected] Recibido: 22-01-2007 Aceptado: 25-05-2007 RESUMEN En este artículo se aborda el análisis de la casuística conocida de reutilizaciones en época romana de lugares prehistóricos de carácter ritual en el Sur de la Península Ibérica. Los casos analizados se agru- pan en tres categorías: (i) proximidad o solapamiento espacial de necrópolis prehistóricas y romanas, (ii) utilización funeraria y cultual de espacios interiores y exteriores de cámaras funerarias prehistóricas, (iii) reutilización de santuarios rupestres y estelas prehistóricas. Como conclusión se sugiere, primero, la nece- sidad de un replanteamiento de los criterios de registro y análisis empírico con que estos casos son abor- dados; segundo, la conveniencia de una reinterpretación completa de los mismos que parta de tener en cuenta los elementos de tradición y memoria que los sitios sagrados tienen dentro de las sociedades ibe- rorromanas; y tercero, su valoración en clave de ideología religiosa e ideología política. PALABRAS CLAVE: Prehistoria Reciente. Historia Antigua. Península Ibérica. Prácticas Funerarias. Ideología Religiosa. Ideología Política. Monumentos. Tradición. Memoria. ABSTRACT This paper tackles the analysis of a series of cases of reutilisation in Roman times of prehistoric sacred spaces and monuments, recorded throughout the South of the Iberian Peninsula. -

Ancient Monuments.Pages

Ancient Monuments of Scotland | Geoffrey Sammons | [email protected] | www.gaelicseattle.com • Heart of Neolithic Orkney • Maeshowe (~2800 BCE): chambered cairn and passage grave which is aligned so the chamber is illuminated on the winter solstice. It was vandalized by Vikings and contains the largest collection of runic writing in the world. • Standing Stones of Stenness (?): Possibly the oldest henge site in Britain and Ireland, this site has 4 stones Broch of Mousa ̤ remaining of what was thought to be 12 in an ellipse. • Ring of Brodgar (~2000 BCE): A henge which uniquely includes the 3rd largest stone circle in Britain and Ireland. • Skara Brae (3180 BCE to 2500 BCE): A cluster of 8 dwellings which constitute Europe’s most complete Neolithic village. Sometimes called the “Scottish Pompeii.” • Callanish Standing Stones (Lewis) • A neolithic stone circle (13 stones) with 5 rows of stones radiating out in a cross-like fashion. Two of the rows are parallel and much longer than the other 3. A chambered tomb, added later, can be found in the center. ̤ Heart of Neolithic Orkney • Kilmartin Glen (Argyll) • There are hundreds of ancient monuments (standing stones, a henge, burials, cairns) to be found within a six mile radius of Kilmartin village. The Kilmartin Museum Base map provides an excellent background for the history of the area (note: check with the museum for opening status as they are about to begin construction of a new facility). There are many pre-planned walks, with maps available, for ̤ Callanish Stones those of various abilities, who wish to see the sites. -

Portico Arqueologia Peninsula Iberica 1999

PÓRTICO LIBRERÍAS http://www.porticolibrerias.es Fundada 1945 Responsable de la Sección: Carmen Alcrudo Dirige: José Miguel Alcrudo ARQUEOLOGÍA DE LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA Guía bibliográfica Zaragoza 1999 ÍNDICE GENERAL PÁGS. Obras generales 2 Prehistoria 59 Colonizaciones 131 Protohistoria 143 Arqueología romana 190 Arqueología medieval 253 Epigrafía — Numismática 294 Revistas 315 Ïndice de autores: 320 OBRAS GENERALES Abad, L. y otros: Arqueología en Alicante, 1976-1986. 1986 – 167 pp., fig. 2.000 Pts. Abad Casal, L. / S. Gutiérrez / R. Sanz: El tolmo de Minateda. Una historia de tres mil quinientos años. 1998 – 162 pp., fot., fig., cuadr. 2.500 Pts. Abascal Palazón, J. M. / R. Sanz Gamo: Bronces antiguos del museo de Albacete. 1993 – 209 pp., fig. 1.560 Pts. Abásolo Álvarez, J. A.: Carta arqueológica de la provincia de Burgos, 1: Parti- dos judiciales de Belorado y Miranda de Ebro. 1974 – 84 pp. 520 Pts. Actas de las primeras jornadas de arqueología de Talavera de la Reina y sus tierras. 1992 – 429 pp., fig., fot. 2.080 Pts. INDICE: Ponencias: F. Jiménez de Gregorio: Aproximación al mapa arqueológico de occidente pro- vincial toledano (del paleolítico inferior a la invasión árabo-beréber) —J. Enamorado Rivero: La ocupación humana del pleistoceno en la comarca de Talavera — M. Fernández-Miranda Fernández / J. Pereira Sieso: Indigenismo y orientalización en la tierra de Talavera — J. Mangas Manajarres / J. Carrobles Santos: La ciudad de Talavera de la Reina en época romana — M. L. Ramos / R. Castelo: Excavaciones en la villa romana de Saucedo. Últimos avances en relación al hallazgo de una basílica paleocristiana — S. Rodríguez Montero / N. -

Wessex Article Master Page

Edinburgh Research Explorer Excavations at Upper Largie Quarry, Argyll & Bute, Scotland Citation for published version: Cook, M, Ellis, C, Sheridan, A, Barber, J, Bonsall, C, Bush, H, Clarke, C, Crone, A, Engl, R, Fouracre, L, Heron, C, Jay, M, McGibbon, F, MacSween, A, Montgomery, J, Pellegrini, M, Sands, R, Saville, A, Scott, D, Šoberl, L & Vandorpe, P 2010, 'Excavations at Upper Largie Quarry, Argyll & Bute, Scotland: new light on the prehistoric ritual landscape of the Kilmartin Glen', Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, vol. 76, pp. 165-212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00000499 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0079497X00000499 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society Publisher Rights Statement: © Cook, M., Ellis, C., Sheridan, A., Barber, J., Bonsall, C., Bush, H., Clarke, C., Crone, A., Engl, R., Fouracre, L., Heron, C., Jay, M., McGibbon, F., MacSween, A., Montgomery, J., Pellegrini, M., Sands, R., Saville, A., Scott, D., Šoberl, L., & Vandorpe, P. (2010). Excavations at Upper Largie Quarry, Argyll & Bute, Scotland: new light on the prehistoric ritual landscape of the Kilmartin Glen. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 76, 165- 212. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation.