Brook Snaketail Ophiogomphus Aspersus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olive Clubtail (Stylurus Olivaceus) in Canada, Prepared Under Contract with Environment Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olive Clubtail Stylurus olivaceus in Canada ENDANGERED 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olive Clubtail Stylurus olivaceus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 58 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Robert A. Cannings, Sydney G. Cannings, Leah R. Ramsay and Richard J. Cannings for writing the status report on Olive Clubtail (Stylurus olivaceus) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Paul Catling, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Arthropods Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le gomphe olive (Stylurus olivaceus) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Olive Clubtail — Photo by Jim Johnson. Permission granted for reproduction. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011. Catalogue No. CW69-14/637-2011E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-18707-5 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2011 Common name Olive Clubtail Scientific name Stylurus olivaceus Status Endangered Reason for designation This highly rare, stream-dwelling dragonfly with striking blue eyes is known from only 5 locations within three separate regions of British Columbia. -

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

Boreal Snaketail

Species Status Assessment Class: Insecta Family: Gomphidae Scientific Name: Ophiogomphus colubrinus Common Name: Boreal snaketail Species synopsis: As its name implies, the boreal snaketail (Ophiogomphus colubrinus) is a species of northern distribution, and it has the most northern range of any clubtail (Mead 2003). The range extends from the western provinces of British Columbia and Alberta, eastward across Canada, to Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick. In the United States, it occurs in Maine, New Hampshire, and New York, as well as in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Wyoming (Needham et al. 2000). O. colubrinus was first documented in New York in 1995, with a number of subsequent records in 1996. All of these records are from the Ausable River in the central Adirondacks, including both the East and West Branch. Some of the recorded locations were documented only by the collection of exuviae. Although the original New York location, the Ausable River along Riverside Drive near Lake Placid, and nearby stretches of the Ausable were searched on several occasions, presence was not documented during the New York State Dragonfly and Damselfly Survey (NYDDS). There is no evidence that changes have occurred in the Ausable River in the vicinity of the previously documented records, so additional surveys would be desirable to confirm the continued presence of this species in New York (White et al. 2010). Previously recorded locations for O. colubrinus in New York are on rivers, principally nearer to the headwaters where the rivers are rapid and shallow with sand, gravel, rock, and boulder substrate, and are primarily bordered by trees and shrubs (New York Natural Heritage Program 2010). -

Ecography ECOG-02578 Pinkert, S., Brandl, R

Ecography ECOG-02578 Pinkert, S., Brandl, R. and Zeuss, D. 2016. Colour lightness of dragonfly assemblages across North America and Europe. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ecog.02578 Supplementary material Appendix 1 Figures A1–A12, Table A1 and A2 1 Figure A1. Scatterplots between female and male colour lightness of 44 North American (Needham et al. 2000) and 19 European (Askew 1988) dragonfly species. Note that colour lightness of females and males is highly correlated. 2 Figure A2. Correlation of the average colour lightness of European dragonfly species illustrated in both Askew (1988) and Dijkstra and Lewington (2006). Average colour lightness ranges from 0 (absolute black) to 255 (pure white). Note that the extracted colour values of dorsal dragonfly drawings from both sources are highly correlated. 3 Figure A3. Frequency distribution of the average colour lightness of 152 North American and 74 European dragonfly species. Average colour lightness ranges from 0 (absolute black) to 255 (pure white). Rugs at the abscissa indicate the value of each species. Note that colour values are from different sources (North America: Needham et al. 2000, Europe: Askew 1988), and hence absolute values are not directly comparable. 4 Figure A4. Scatterplots of single ordinary least-squares regressions between average colour lightness of 8,127 North American dragonfly assemblages and mean temperature of the warmest quarter. Red dots represent assemblages that were excluded from the analysis because they contained less than five species. Note that those assemblages that were excluded scatter more than those with more than five species (c.f. the coefficients of determination) due to the inherent effect of very low sampling sizes. -

Introduction to Odonata: Dragonflies & Damselflies

Introduction to Odonata: Dragonflies & Damselflies Ornate Pennant (Celithemis ornata), C. Mazzacano What are odonates? “toothed” fossil record >400 million years Proto-fossils from Permian with 27 in. (68 cm) wingspan Protolindenia wittei fossil; 155 million y.o.; www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/arthropoda/uniramia/odonatoida.html What are odonates? Diverse; 5952 species globally 463 species in North America (Schorr & Paulson, 2013) Blue Dasher (Pachydiplax longipennis), C. Mazzacano Anisoptera (dragonflies) Zygoptera (damselflies) Sierra Madre Dancer (Argia lacrimans), C. Mazzacano What are odonates? Colorful Double-striped Bluet (Enallagma basidens), C. Mazzacano Ebony Jewelwing, (Calopteryx maculata) John Wallace What are odonates? Aquatic Alexa Carleton Celeste Mazzacano What are odonates? Hunters… Dennis Paulson …and prey Larry Rea What are odonates? Symbolic Gila National Forest; USFS Alexa Carleton Petroglyph National Monument What are odonates? American Rubyspot (Hetaerina cruentata), C. Mazzacano Variable Darner (Aeshna interrupta), C. Mazzacano Beautiful! Eastern Amberwing (Perithemis tenera), John Abbott Carmine Skimmer (Orthemis discolor), C. Mazzacano Dragonfly or damselfly? Common Green Darner (Anax junius), Dennis Paulson Powdered Dancer (Argia moesta), C. Mazzacano Large body Smaller body Wider abdomen Slender abdomen Eyes touch or nearly so Eyes separated Hindwings broader than Equal-sized wings forewings stalked at base Wings held horizontal Wings folded above or along when perched body when perched Odonate habitats Bear Creek CA; C. Mazzacano Cache la Poudre River CO; C. Mazzacano Running water: rivers, streams, creeks, ditches Whychus Creek OR; C. Mazzacano Sandy River OR; C. Mazzacano Odonate habitats Deweys Mill Pond, Quechee VT; C. Mazzacano RAMSAR wetland, Xalapa Mexico; C. Mazzacano Still water: marsh, swamp, bog, seep, wet meadow, lake, pond Kristi Lake bog, Saskatchewan Canada; C. -

A Checklist of North American Odonata

A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009 Edition (updated 14 April 2009) A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution 2009 Edition (updated 14 April 2009) Dennis R. Paulson1 and Sidney W. Dunkle2 Originally published as Occasional Paper No. 56, Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, June 1999; completely revised March 2009. Copyright © 2009 Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009 edition published by Jim Johnson Cover photo: Tramea carolina (Carolina Saddlebags), Cabin Lake, Aiken Co., South Carolina, 13 May 2008, Dennis Paulson. 1 1724 NE 98 Street, Seattle, WA 98115 2 8030 Lakeside Parkway, Apt. 8208, Tucson, AZ 85730 ABSTRACT The checklist includes all 457 species of North American Odonata considered valid at this time. For each species the original citation, English name, type locality, etymology of both scientific and English names, and approxi- mate distribution are given. Literature citations for original descriptions of all species are given in the appended list of references. INTRODUCTION Before the first edition of this checklist there was no re- Table 1. The families of North American Odonata, cent checklist of North American Odonata. Muttkows- with number of species. ki (1910) and Needham and Heywood (1929) are long out of date. The Zygoptera and Anisoptera were cov- Family Genera Species ered by Westfall and May (2006) and Needham, West- fall, and May (2000), respectively, but some changes Calopterygidae 2 8 in nomenclature have been made subsequently. Davies Lestidae 2 19 and Tobin (1984, 1985) listed the world odonate fauna Coenagrionidae 15 103 but did not include type localities or details of distri- Platystictidae 1 1 bution. -

Pygmy Snaketail, Ophiogomphus Howei, Prepared Under Contract with Environment and Climate Change Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Pygmy Snaketail Ophiogomphus howei in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2018 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2018. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Pygmy Snaketail Ophiogomphus howei in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 46 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Pygmy Snaketail Ophiogomphus howei in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 34 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge John Klymko for writing the status report on Pygmy Snaketail, Ophiogomphus howei, prepared under contract with Environment and Climate Change Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Paul Grant, COSEWIC Arthropods Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment and Climate Change Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur L’ophiogomphe de Howe (Ophiogomphus howei) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Pygmy Snaketail — Cover photo by: Denis Doucet. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018. Catalogue No. CW69-14/542-2019E-PDF ISBN 978-0-660-31321-4 COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2018 Common name Pygmy Snaketail Scientific name Ophiogomphus howei Status Special Concern Reason for designation One of Canada’s smallest dragonflies, this globally-rare species is a habitat specialist, restricted to a few rivers in New Brunswick and a single river in northwestern Ontario. -

Full Volume 50 Nos. 1&2

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 50 Numbers 1 & 2 -- Spring/Summer 2017 Article 12 Numbers 1 & 2 -- Spring/Summer 2017 September 2017 Full Volume 50 Nos. 1&2 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation 2017. "Full Volume 50 Nos. 1&2," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 50 (1) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol50/iss1/12 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. et al.: Full Volume 50 Nos. 1&2 Vol. 50, Nos. 1 & 2 Spring/Summer 2017 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST PUBLISHED BY THE MICHIGAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY Published by ValpoScholar, 2017 1 The Great Lakes Entomologist, Vol. 50, No. 1 [2017], Art. 12 THE MICHIGAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2016–17 OFFICERS President Robert Haack President Elect Matthew Douglas Immediate Pate President Angie Pytel Secretary Adrienne O’Brien Treasurer Angie Pytel Member-at-Large (2016-2018) John Douglass Member-at-Large (2016-2018) Martin Andree Member-at-Large (2015-2018) Bernice DeMarco Member-at-Large (2014-2017) Mark VanderWerp Lead Journal Scientific Editor Kristi Bugajski Lead Journal Production Editor Alicia Bray Associate Journal Editor Anthony Cognato Associate Journal Editor Julie Craves Associate Journal Editor David Houghton Associate Journal Editor William Ruesink Associate Journal Editor William Scharf Associate Journal Editor Daniel Swanson Newsletter Editor Matthew Douglas and Daniel Swanson Webmaster Mark O’Brien The Michigan Entomological Society traces its origins to the old Detroit Entomological Society and was organized on 4 November 1954 to “. -

2015-2025 Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species Assessments Appendix 1.1A – Birds A Comprehensive Status Assessment of Pennsylvania’s Avifauna for Application to the State Wildlife Action Plan Update 2015 (Jason Hill, PhD) Assessment of eBird data for the importance of Pennsylvania as a bird migratory corridor (Andy Wilson, PhD) Appendix 1.1B – Mammals A Comprehensive Status Assessment of Pennsylvania’s Mammals, Utilizing NatureServe Ranking Methodology and Rank Calculator Version 3.1 for Application to the State Wildlife Action Plan Update 2015 (Charlie Eichelberger and Joe Wisgo) Appendix 1.1C – Reptiles and Amphibians A Revision of the State Conservation Ranks of Pennsylvania’s Herpetofauna Appendix 1.1D – Fishes A Revision of the State Conservation Ranks of Pennsylvania’s Fishes Appendix 1.1E – Invertebrates Invertebrate Assessment for the 2015 Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan Revision 2015-2025 Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan Appendix 1.1A - Birds A Comprehensive Status Assessment of Pennsylvania’s Avifauna for Application to the State Wildlife Action Plan Update 2015 Jason M. Hill, PhD. Table of Contents Assessment ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Data Sources ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Species Selection ................................................................................................................................ -

Riffle Snaketail & Endangered Species Ophiogomphus Carolus Program

Natural Heritage Riffle Snaketail & Endangered Species Ophiogomphus carolus Program www.mass.gov/nhesp State Status: Threatened Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Federal Status: None DESCRIPTION: The Riffle Snaketail (Ophiogomphus dorsal abdominal markings differ between species and carolus) is a large, stocky insect belonging to the order may help to identify the various species of Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies). The Ophiogomphus. However, these markings can be clubtails (family Gomphidae), to which this species variable and should be used in combination with other belongs, are one of the most diverse families of factors to make definitive identifications. The most dragonflies in North America with nearly 100 species. reliable way to distinguish males of the genus Clubtails are unique among the dragonflies in having Ophiogomphus from each other is by examination of the eyes that are separated from each other. These insects, as terminal abdominal appendages and hamules (organs their name implies, have a lateral swelling near the end located on the underside of segment 2) (as shown in of the abdomen which gives it a club-like appearance. Walker (1958) and Needham et al.(2000)). Females may The Riffle Snaketail is a member of the genus be identified to species by the shape of their vulvar Ophiogomphus (the snaketails). These dragonflies are lamina (located underneath segments eight and nine) and characterized by their brilliant green thorax, eyes and by the shape of small spines and bumps located on top of face. The swelling in the abdomen of the Riffle Snaketail the head (as shown in Walker (1958) and Needham et al. -

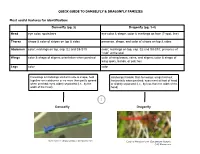

Dragonfly (Pg. 3-4) Head Eye Color

QUICK GUIDE TO DAMSELFLY & DRAGONFLY FAMILIES Most useful features for identification: Damselfly (pg. 2) Dragonfly (pg. 3-4) Head eye color; spots/bars eye color & shape; color & markings on face (T-spot, line) Thorax shape & color of stripes on top & sides presence, shape, and color of stripes on top & sides Abdomen color; markings on top, esp. S2 and S8-S10 color; markings on top, esp. S2 and S8-S10; presence of “club” at the end Wings color & shape of stigma; orientation when perched color of wing bases, veins, and stigma; color & shape of wing spots, bands, or patches Legs color color Forewings & hindwings similar in size & shape, held Hindwings broader than forewings; wings held out together over abdomen or no more than partly spread horizontally when perched; eyes meet at front of head when perched; eyes widely separated (i.e., by the or slightly separated (i.e., by less than the width of the width of the head) head) 1 Damselfly Dragonfly Vivid Dancer (Argia vivida); CAS Mazzacano Cardinal Meadowhawk (Sympetrum illotum); CAS Mazzacano DAMSELFLIES Wings narrow, stalked at base 2 Wings broad, colored, not stalked at base 3 Wings held askew Wings held together Broad-winged Damselfly when perched when perched (Calopterygidae); streams Spreadwing Pond Damsels (Coenagrionidae); (Lestidae); ponds ponds, streams Dancer (Argia); Wings held above abdomen; vivid colors streams 4 Wings held along Bluet (Enallagma); River Jewelwing (Calopteryx aequabilis); abdomen; mostly blue ponds CAS Mazzacano Dark abdomen with blue Forktail (Ischnura); tip; -

Agrion 22(2) - July 2018 AGRION NEWSLETTER of the WORLDWIDE DRAGONFLY ASSOCIATION

Agrion 22(2) - July 2018 AGRION NEWSLETTER OF THE WORLDWIDE DRAGONFLY ASSOCIATION PATRON: Professor Edward O. Wilson FRS, FRSE Volume 22, Number 2 July 2018 Secretary: Dr. Jessica I. Ware, Assistant Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, 206 Boyden Hall, Rutgers University, 195 University Avenue, Newark, NJ 07102, USA. Email: [email protected]. Editors: Keith D.P. Wilson. 18 Chatsworth Road, Brighton, BN1 5DB, UK. Email: [email protected]. Graham T. Reels. 31 St Anne’s Close, Badger Farm, Winchester, SO22 4LQ, Hants, UK. Email: [email protected]. ISSN 1476-2552 Agrion 22(2) - July 2018 AGRION NEWSLETTER OF THE WORLDWIDE DRAGONFLY ASSOCIATION AGRION is the Worldwide Dragonfly Association’s (WDA’s) newsletter, published twice a year, in January and July. The WDA aims to advance public education and awareness by the promotion of the study and conservation of dragonflies (Odonata) and their natural habitats in all parts of the world. AGRION covers all aspects of WDA’s activities; it communicates facts and knowledge related to the study and conservation of dragonflies and is a forum for news and information exchange for members. AGRION is freely available for downloading from the WDA website at [https://worlddragonfly.org/publications/]. WDA is a Registered Charity (Not-for-Profit Organization), Charity No. 1066039/0. A ‘pdf’ of the WDA’s Constitutionand and byelaws can be found at its website link at [https://worlddragonfly. org/wda/] ________________________________________________________________________________ Editor’s notes Keith Wilson [[email protected]] WDA Membership There are several kinds of WDA membership available either with or without the WDA’s journal (The International Journal of Odonatology).