The Postmodern Playground of Terry Pratchett's Discworld Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Annotated Pratchett File, V9.0

The Annotated Pratchett File, v9.0 Collected and edited by: Leo Breebaart <[email protected]> Assistant Editor: Mike Kew <[email protected]> Organisation: Unseen University Newsgroups: alt.fan.pratchett,alt.books.pratchett Archive name: apf–9.0.5 Last modified: 2 February 2008 Version number: 9.0.5 (The Pointless Albatross Release) The Annotated Pratchett File 2 CONTENTS 1 Preface to v9.0 5 The Last Hero . 135 The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents . 137 2 Introduction 7 Night Watch . 138 3 Discworld Annotations 9 The Wee Free Men . 140 The Colour of Magic . 9 Monstrous Regiment . 143 The Light Fantastic . 14 A Hat Full of Sky . 147 Equal Rites . 17 Once More, With Footnotes . 148 Mort . 19 Going Postal . 148 Sourcery . 22 Thud . 148 Wyrd Sisters . 26 Where’s My Cow? . 148 Pyramids . 31 Wintersmith . 148 Guards! Guards! . 37 Making Money . 148 Eric . 40 I Shall Wear Midnight . 149 Moving Pictures . 43 Unseen Academicals . 149 Reaper Man . 47 Scouting for Trolls . 149 Witches Abroad . 53 Raising Taxes . 149 Small Gods . 58 The Discworld Companion . 149 Lords and Ladies . 65 The Science of Discworld . 150 Men at Arms . 72 The Science of Discworld II: the Globe . 151 Soul Music . 80 The Science of Discworld III: Darwin’s Watch . 151 Interesting Times . 90 The Streets of Ankh-Morpork . 151 Maskerade . 93 The Discworld Mapp . 151 Feet of Clay . 95 A Tourist Guide to Lancre . 151 Hogfather . 103 Death’s Domain . 152 Jingo . 110 4 Other Annotations 153 The Last Continent . 116 Good Omens . 153 Carpe Jugulum . 123 Strata . 160 The Fifth Elephant . -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Terry Pratchett -A (Disc) World of Collecting

TERRY PRATCHETT -A (DISC) WORLD OF COLLECTING Colin Steele Background Terrence David John Pratchett - Terry Pratchett - is the author of the phenomenally successful Discworld series and is one of contemporary fiction’s most popular writers. Since Nielsen's records began in 1998, Pratchett has sold around 10 million books in the UK, generating more than £70 million in revenue. His agent and original publisher, Colin Smythe says Pratchett has either written, co-written or been creatively associated with 100-plus books, notably Discworld titles, Despite this prodigious output, Pratchett is one of the UK’s most collectable authors, particularly for his early books and special editions. Pratchett‘s first book, The Carpet People, was published in 1971, while his first Discworld novel, The Colour of Magic, appeared in 1983. 36 more Discworld books have followed, many of which have topped the UK hardback and paperback lists. Pratchett's novels have sold more than 60 million copies and have been translated into 33 languages Until Pratchett’s recent diagnosis of an early stage of a rare form of Alzheimer’s disease, he usually wrote two books a year, which reputedly earned him £1 million each. When asked “What do you love most about your job? “ Pratchett replied “Well, I get paid shitloads of cash...which is good”. Pratchett donated £500,000 towards Alzheimer’s research in March 2008. Pratchett anticipates dictating novels from 2009 onwards due to his illness. He recently told the BBC, that compared to his once rapid typing, that he now types “badly - if it wasn’t for my loss of typing ability, I might doubt the fact that I have Alzheimer’s. -

Evolution Program Book

EVOLUTION INTUITION A Bid for the 1998 Eastercon Opening the Doors of the Mind creation, dreams, philosophy and game playing.. Opening the Doors into the Future near future, science & technology... Opening the Doors into the Past [line travel, origins of SF, myths and legend... Come and see us at our desk at Evolution: all your questions answered; programme philosophy; information about Manchester; floor plans of the hotel and more... Intuition is a bid to hold the 1998 British INTUITIVES National Science Fiction Convention in the Piccidilly Jarvis Hotel in city-centre Claire Brialey - Chair Manchester. Helen Steele - Programme & Publications Conceived over 15 months ago. Intuition has developed into a bid with a strong Fran Dowd - Finance committee, plenty of ideas, a Kathy Taylor - Memberships commitment to a strong, literate programme with elements for all Jenny Glover - Secretary sections of fandom and the opportunity for all levels of participation. Fiona Anderson - Ops The hotel is exceptional: ideally placed, Laura Wheatly - Site it has recently been refurbished with Alice Lawson - Extraveganzas excellent facilities, including a video room with built in screen, full Amanda Baker - Science & soundproofing in all rooms: three large WWW bars and much more social space. And all at a reasonable price! Contact: 43 Onslow Gdns, Wallington, Surrey SM6 9QF1, [email protected] INTRODUCTION Cripes, a talking chair..................................................................... 3 Welcome to Evolution! Our chair would like a quick word. GUESTS AND GAMBOLS On the Growth and Cultivation of Jute.......................................4 How does a character evolve out of the mind of her creator, onto paper and off into the world on her own? Colin Greenland deconstructs. -

A Close and Distant Reading of Shakespearean Intertextuality

OPEN PUBLISHING IN THE HUMANITIES JOHANNES MOLZ A Close and Distant Reading of Shakespearean Intertextuality Towards a mixed methods approach for literary studies Johannes Molz A Close and Distant Reading of Shakespearean Intertextuality. Towards a Mixed Methods Approach for Literary Studies Open Publishing in the Humanities The publication series Open Publishing in the Humanities (OPH) enables to support the publication of selected theses submitted in the humanities and social sciences. This support package from LMU is designed to strengthen the Open Access principle among young researchers in the humanities and social sciences and is aimed speci f - cally at those young scholars who have yet to publish their theses and who are also particularly research-oriented. The OPH publication series is under the editorial management of Prof. Dr Hubertus Kohle and Prof. Dr Thomas Krefeld. The University Library of the LMU will publish selected theses submitted by out - standing junior LMU researchers in the humanities and social sciences both on Open Access and in print. https://oph.ub.uni-muenchen.de A Close and Distant Reading of Shakespearean Intertextuality Towards a mixed methods approach for literary studies by Johannes Molz Published by University Library of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München Funded by Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Text © Johannes Molz 2020 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. -

Years 7 & 8 Hall Grove Reading List September 2013

Years 7 & 8 Hall Grove Reading List September 2013 By Years 7 and 8 the children are being prepared for life at Senior School and beyond, and should be engaging more with the world around them; in particular that means being exposed to other points of view and other cultures. Consequently this reading list, in some small way, is an attempt to highlight particular authors and texts that will help them in that journey. This list is revised annually to take account of changing tastes amongst year groups and to include more recently published or discovered books. The first section is a rough collection of recommendations in different genres – all books that I’ve particularly enjoyed. The remainder of the current list is based on what might be expected and suitable, and also on what Senior Schools suggest the children may have come across. I have tried to build in a sense of progression in subject matter and technical difficulties. Most of the list consists of fiction – some written for children, some for adults; as such, some of the topics and language are more mature in outlook and this needs to be taken into account when selecting books to read. The lists for younger children are also available on through the school web-site – www.hallgrove.co.uk – go to the Academic section, English, and there are links to all Reading Lists on the right of the page. Whilst not all of these books are in the school library, many of them are; the children should make good use of our library (and other libraries) to look for new authors, to dip into books and to recommend books. -

Iwacora G WEST the WOMBAT SPEAKETH I Take Great Pleasure in Welcoming You to NOVACON 9 WEST

iwacora g WEST THE WOMBAT SPEAKETH I take great pleasure in welcoming you to NOVACON 9 WEST. It has teen along and yet interesting 18 month haul. I do hope you’ll have a good time, I certainly plan to. endeavor I’ve had the help of countless millions, well not quite, but certainly a large number persons without whom we’d all have nothing to do this weekend. pj-iere VqH lots to do and see this weekend. The total programme is varied and it is to be hoped that you will find much of interest to you. at every con there will be mundanes around. Thus, please wear your name badges at all time. With exception of the video room no one will be admitted to any function area sans name tag. Sq let,s get Qn another family reunion. Oldtimers (those of you for whom this is at least your second con) know what I mean. For you bushy-eyed and bright-tailed neons, relax, don’t be shy about saying hi to what seem to be strangers, they won’t be very shortly, and use your good sense in intro ductions. a -beyovKi hope and the length of time we have for me to get to chat with each and everyone of you as I'd like. However, I shall be most often found sitting quietly in the con suite gibbering softly to mesel: Do come by and pat me on the head, while murmurring soft condolences for me breakdown. With some help from me friends I'll recover in time for next year. -

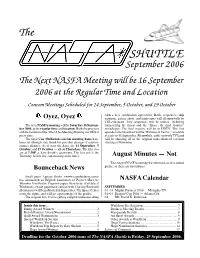

NASFA 'Shuttle' Sep 2006

The SHUTTLE September 2006 The Next NASFA Meeting will be 16 September 2006 at the Regular Time and Location Concom Meetings Scheduled for 14 September, 5 October, and 19 October { { with a new syndication agreement. Battle sequences, ship Oyez, Oyez exteriors, galaxy shots, and landscapes will all reportedly be CGI-enhanced. Title sequences will be redone, including The next NASFA meeting will be Saturday 16 Septem- remastering the music and the ÒSpace, the final frontierÓ ber 2006, at the regular time and location. Both the program monologue. The final masters will be in HDTV. The first and the location of the After-The-Meeting Meeting are TBD at episode to be broadcast will be ÒBalance of Terror,Ó available press time. as early as 16 September. Meanwhile, cable network TV Land The final Con Stellation concom meeting dates have will be showing all of the original non-enhanced versions been set (though stay tuned for possible changes if circum- starting in November. stances dictate). As of now the dates are 14 September, 5 October, and 19 October Ñ all on Thursdays. The first two are at 7:30P at Sam SmithÕs apartment. The last one is the Thursday-before-the-con meeting at the hotel. August Minutes Ñ Not The August NASFA meeting was the more-or-less annual Bounceback News picnic, so there are no minutes. Small press Apogee Books <www.cgpublishing.com> has announced an English translation of Project Mars by NASFA Calendar Wernher Von Braun. Preprint copies were to be available at Worldcon; a trade paperback edition with Chesley Bonestell SEPTEMBER illustrations will be published in September. -

Buberian Dialogue

Restoring Dialogue to Political Debate A Modest Proposal October 2005 Institute for the Study of Coherence and Emergence http://isce.edu 2338 Immokalee Rd. #292, Naples, FL 34110 239-254-9648 Summary ISCE proposes to hold two one day events in Washington DC, a one day event in Budapest Hungary, and a three day conference in Naples Florida to experiment with the technique known as Buberian Dialogue. The goal of these experiments is to see if the use of Buberian Dialogue can provide transformative experiences for prominent political commentators and therby transform the quantity or quality of political stridency demonstrated in the media. Stridency and polarization dominate the conduct of political debate in the media. Like the endless repetition of a bad song, the melody becomes stuck in the public’s consciousness and like a squeaky wheel attracts undue attention and energy. Many recognize this problem but as with the problem of drug addiction feel mostly powerless to contain it … never mind stop it. When the head of a political party can claim, “This is a struggle of good and evil. And we're the good." the visceral stridency is nearing crescendo. Something needs to be done. Attempts to promote “dialogue” have traditionally been conducted along one of two paths – the line promoted by the Nobel prize winning physicist David Bohm – participants in a dialogue must attempt to put aside their partisan differences and enter into a “cooperative space” open to the generation of new ideas or the line promoted by “political realists” where the goal is compromise and partial victories. -

Science of Discworld Terry Pratchett Ian Stewart Jack Cohen Bok PDF

Science Of Discworld Ladda ner boken PDF Terry Pratchett Ian Stewart Jack Cohen Science Of Discworld Terry Pratchett Ian Stewart Jack Cohen boken PDF In the 'fantasy' universe of the phenomenally bestselling Discworld series, everything runs on magic and common sense. The world is flat and million-to-one chances happen nine times out of ten. Our world seems different - it runs on rules, often rather strange ones. Science is our way of finding out what those rules are. The appeal of Discworld is that it mostly makes sense, in a way that particle physics does not. The Science of Discworld uses the magic of Discworld to illuminate the scientific rules that govern our world. When a wizardly experiment goes adrift, the wizards of Unseen University find themselves with a pocket universe on their hands: Roundworld, where neither magic nor common sense seems to stand a chance against logic. Roundworld is, of course, our own universe. With us inside it (eventually). Guided (if that's the word) by the wizards, we follow its story from the primal singularity of the Big Bang to the Internet and beyond. We discover how puny and insignificant individual lives are against a cosmic backdrop of creation and disaster. Yet, paradoxically, we see how the richness of a universe based on rules has led to a complex world and at least one species that tried to get a grip on what was going on. Download (Laste ned) pdf-boken, pdf boken, pdf E-böcker, epub, fb2 Alla böcker. 30 dagars gratis provperiod. -

Science Communication @ Europlex

“Lies-to-Children” in Science Communication Ernesto Lozano Tellechea Physics editor of Investigación y Ciencia Spanish edition of Scientific American EuroPLEX partner Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 What are lies to children? = BAD Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 What are lies to children? NOT THAT BAD AFTER ALL… Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 What are lies-to-children? • Concept in science education. • Simplified versions of a subject. • The purpose is NOT to fool, rather – give the main idea, – give the tools to move beyond. This is actually what I just did with the Calvin strip Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 What are lies-to-children? • Examples in physics: – Ideal gases, – Newtonian gravity, – Geometrical optics, – Bohr atomic model, – … Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 Outlook of this talk • Why lies-to-children is also a very useful analytical tool in science communication. • Lies-to-children pros & cons. • Why QCD needs lies. • Take it as a challenge: QuarkBits. Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 Origins of the concept • First popularized in the sci-fi novel The Science of Discworld (1999) Terry Pratchett, Ian Stewart, Jack Cohen Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 Origins of the concept • First popularized in the sci-fi novel The Science of Discworld (1999) "A lie-to-children is a statement that is false, but which nevertheless leads the child's mind towards a more accurate explanation, one that the child will only be able to appreciate if it has been primed with the lie" Dublin 2020 – EuroPLEx Progress Workshop Nov 30 – Dec 3, 2020 In science communication • Sci-comm: Popular accounts of a complex scientific subject aimed to a lay audience. -

The Annotated Pratchett File, V7a.5

The Annotated Pratchett File, v7a.5 Collected and edited by: Leo Breebaart <[email protected]> Assistant Editor: Mike Kew <[email protected]> Organisation: Unseen University Newsgroups: alt.fan.pratchett,alt.books.pratchett Archive name: apf–7a.5.3.5 Last modified: 25 July 2002 Version number: 7a.5.3.5 Contents 1 Preface to v7a.5 5 2 Introduction 7 3 Editorial Comments for v7a.5 9 PAGE NUMBERS . 9 OTHER ANNOTATIONS . 10 4 Discworld Annotations 11 THE COLOUR OF MAGIC . 11 THE LIGHT FANTASTIC . 22 EQUAL RITES . 28 MORT.................................... 32 SOURCERY . 39 WYRD SISTERS . 48 PYRAMIDS . 59 GUARDS! GUARDS! . 71 ERIC . 79 MOVING PICTURES . 84 REAPER MAN . 94 WITCHES ABROAD . 106 SMALL GODS . 118 LORDS AND LADIES . 132 MEN AT ARMS . 148 SOUL MUSIC . 164 INTERESTING TIMES . 187 2 APF v7a.5.3.4, April 2002 MASKERADE . 193 FEET OF CLAY . 199 HOGFATHER . 215 JINGO . 231 THE LAST CONTINENT . 244 CARPE JUGULUM . 258 THE FIFTH ELEPHANT . 271 THE TRUTH . 271 THIEF OF TIME . 271 THE LAST HERO . 271 THE AMAZING MAURICE AND HIS EDUCATED RODENTS . 272 NIGHT WATCH . 272 THE WEE FREE MEN . 272 THE 2003 DISCWORLD NOVEL . 272 THE 2004 DISCWORLD NOVEL . 273 THE DISCWORLD COMPANION . 273 THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD . 276 THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD II: THE GLOBE . 276 THE STREETS OF ANKH-MORPORK . 276 THE DISCWORLD MAPP . 276 A TOURIST GUIDE TO LANCRE . 276 DEATH’S DOMAIN . 277 5 Other Annotations 279 GOOD OMENS . 279 STRATA . 295 THE DARK SIDE OF THE SUN . 296 TRUCKERS . 298 DIGGERS . 300 WINGS . 301 ONLY YOU CAN SAVE MANKIND . 302 JOHNNY AND THE DEAD .