Arxiv:2104.14972V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 May 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual/Infrared Interferometry of Orion Trapezium Stars: Preliminary Dynamical Orbit and Aperture Synthesis Imaging of the Θ1 Orionis C System

A&A 466, 649–659 (2007) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20066965 & c ESO 2007 Astrophysics Visual/infrared interferometry of Orion Trapezium stars: preliminary dynamical orbit and aperture synthesis imaging of the θ1 Orionis C system S. Kraus1, Y. Y. Balega2, J.-P. Berger3, K.-H. Hofmann1, R. Millan-Gabet4, J. D. Monnier5, K. Ohnaka1, E. Pedretti5, Th. Preibisch1, D. Schertl1, F. P. Schloerb6, W. A. Traub7, and G. Weigelt1 1 Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Special Astrophysical Observatory, Russian Academy of Sciences, Nizhnij Arkhyz, Zelenchuk region, Karachai-Cherkesia 357147, Russia 3 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Grenoble, UMR 5571 Université Joseph Fourier/CNRS, BP 53, 38041 Grenoble Cedex 9, France 4 Michelson Science Center, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5 Astronomy Department, University of Michigan, 500 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104, USA 6 Department of Astronomy, University of Massachusetts, LGRT-B 619E, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02183, USA Received 19 December 2006 / Accepted 7 February 2007 ABSTRACT Context. Located in the Orion Trapezium cluster, θ1Ori C is one of the youngest and nearest high-mass stars (O5-O7) known. Besides its unique properties as a magnetic rotator, the system is also known to be a close binary. Aims. By tracing its orbital motion, we aim to determine the orbit and dynamical mass of the system, yielding a characterization of the individual components and, ultimately, also new constraints for stellar evolution models in the high-mass regime. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

The 10 Parsec Sample in the Gaia Era?,?? C

A&A 650, A201 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140985 & c C. Reylé et al. 2021 Astrophysics The 10 parsec sample in the Gaia era?,?? C. Reylé1 , K. Jardine2 , P. Fouqué3 , J. A. Caballero4 , R. L. Smart5 , and A. Sozzetti5 1 Institut UTINAM, CNRS UMR6213, Univ. Bourgogne Franche-Comté, OSU THETA Franche-Comté-Bourgogne, Observatoire de Besançon, BP 1615, 25010 Besançon Cedex, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Radagast Solutions, Simon Vestdijkpad 24, 2321 WD Leiden, The Netherlands 3 IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, 14 av. E. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 4 Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino bajo del castillo s/n, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 5 INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Via Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy Received 2 April 2021 / Accepted 23 April 2021 ABSTRACT Context. The nearest stars provide a fundamental constraint for our understanding of stellar physics and the Galaxy. The nearby sample serves as an anchor where all objects can be seen and understood with precise data. This work is triggered by the most recent data release of the astrometric space mission Gaia and uses its unprecedented high precision parallax measurements to review the census of objects within 10 pc. Aims. The first aim of this work was to compile all stars and brown dwarfs within 10 pc observable by Gaia and compare it with the Gaia Catalogue of Nearby Stars as a quality assurance test. We complement the list to get a full 10 pc census, including bright stars, brown dwarfs, and exoplanets. -

Manual for Visual Observing of Variable Stars

AAVSO Manual for Visual Observing of Variable Stars Revised Edition January 2001 The American Association of Variable Star Observers 25 Birch Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 U. S. A. Tel: 617-354-0484 Fax: 617-354-0665 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.aavso.org COPYRIGHT 2001 by the American Association of Variable Star Observers 25 Birch Street Cambridge, MA 02138 U. S. A. ISBN 1-878174-32-0 ii FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with great pleasure that we present this revised and improved edition of the Manual for Visual Observing of Variable Stars. This manual is intended to be a comprehensive guide to variable star observing. It incorporates a lot of the basic information in the Manual for Observing Variable Stars, published in 1970 by the former Director of the AAVSO, Margaret W. Mayall, as well as information from various AAVSO observing materials published since then. This manual provides up-to-date information for making variable star observations and reporting them to the AAVSO. For new observers, this manual is an essential tool—the one place from which one can gather all the information needed in order to start a variable star observing program. Long-time and experienced observers, and those returning to variable star observing, on the other hand, may find it useful as a ready-reference, quick-resource, or refresher text to help explore new aspects of variable star observing. This manual will familiarize you with the standardized processes and procedures of variable star observing—a very important part of making and submitting your observations to the AAVSO. -

Near Infrared Spectroscopy of M Dwarfs. I. CO Molecule As an Abundance Indicator of Carbon ∗

PASJ: Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan , 1–??, c 2014. Astronomical Society of Japan. Near Infrared Spectroscopy of M Dwarfs. I. CO Molecule as an Abundance Indicator of Carbon ∗ Takashi Tsuji Institute of Astronomy, The University of Tokyo, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka-shi, Tokyo, 181-0015 [email protected] and Tadashi Nakajima National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka-shi, Tokyo, 181-8588 [email protected] (Received ; accepted ) Abstract Based on the near infrared spectra of 42 M dwarfs, carbon abundances are determined from the ro- vibrational lines of CO 2-0 band. We apply Teff values based on the angular diameters (15 objects) and on the infrared flux method (2 objects) or apply a simple new method using a log Teff (by the angular diameters and by the infrared flux method) – M3.4 (the absolute magnitude at 3.4 µm based on the WISE W 1 flux and the Hipparcos parallax) relation to estimate Teff values of objects for which angular diameters are unknown (25 objects). Also, we discuss briefly the HR diagram of low mass stars. On the observed spectrum of the M dwarf, the continuum is depressed by the numerous weak lines of H2O and only the depressed continuum or the pseudo-continuum can be seen. On the theoretical spectrum of the M dwarf, the true continuum can be evaluated easily but the pseudo-continuum can also be evaluated accurately thanks to the recent H2O line database. Then spectroscopic analysis of the M dwarf can be done by referring to the pseudo-continua both on the observed and theoretical spectra. -

![Arxiv:1207.6212V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 1 Aug 2012](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8507/arxiv-1207-6212v2-astro-ph-ga-1-aug-2012-3868507.webp)

Arxiv:1207.6212V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 1 Aug 2012

Draft: Submitted to ApJ Supp. A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 PRECISE RADIAL VELOCITIES OF 2046 NEARBY FGKM STARS AND 131 STANDARDS1 Carly Chubak2, Geoffrey W. Marcy2, Debra A. Fischer5, Andrew W. Howard2,3, Howard Isaacson2, John Asher Johnson4, Jason T. Wright6,7 (Received; Accepted) Draft: Submitted to ApJ Supp. ABSTRACT We present radial velocities with an accuracy of 0.1 km s−1 for 2046 stars of spectral type F,G,K, and M, based on ∼29000 spectra taken with the Keck I telescope. We also present 131 FGKM standard stars, all of which exhibit constant radial velocity for at least 10 years, with an RMS less than 0.03 km s−1. All velocities are measured relative to the solar system barycenter. Spectra of the Sun and of asteroids pin the zero-point of our velocities, yielding a velocity accuracy of 0.01 km s−1for G2V stars. This velocity zero-point agrees within 0.01 km s−1 with the zero-points carefully determined by Nidever et al. (2002) and Latham et al. (2002). For reference we compute the differences in velocity zero-points between our velocities and standard stars of the IAU, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and l’Observatoire de Geneve, finding agreement with all of them at the level of 0.1 km s−1. But our radial velocities (and those of all other groups) contain no corrections for convective blueshift or gravitational redshifts (except for G2V stars), leaving them vulnerable to systematic errors of ∼0.2 km s−1 for K dwarfs and ∼0.3 km s−1 for M dwarfs due to subphotospheric convection, for which we offer velocity corrections. -

Design of a Space-Based Laser Guide Star Mission to Enable Ground and Space Telescope Observations of Faint Objects

Design of a Space-Based Laser Guide Star Mission to Enable Ground and Space Telescope Observations of Faint Objects Jim Clark ([email protected]), Greg Allan, Kerri Cahoy, Yinzi Xin Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ewan Douglas, Jennifer Lumbres, Jared Males University of Arizona 1 Overview ● Motivation: Imaging faint objects ● Background: Why satellite LGS? ● Approach and results: ○ Spacecraft design and L2 mission operations ○ Earth-orbiting pathfinder ○ Optical testbed ● Summary and future work 2 Motivation: imaging faint objects ● Seeing dim things near bright things: ○ Exoplanets ○ Asteroids ○ Space situational awareness ● Enabling technologies: coronography and adaptive optics ○ DeMi will demonstrate the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Deformable_mirror_correction.svg AO actuators, but still need a very bright reference star for faint objects 3 Background: why satellite LGS? ● LUVOIR segment stability must be ~picometers for exoplanet imaging ○ Hard/expensive/impossible(?) to build https://asd.gsfc.nasa.gov/luvoir/design/ 4 Background: Why satellite LGS? ● LUVOIR segment stability must be ~picometers for exoplanet imaging ○ Hard/expensive/impossible(?) to build ● Not many natural guide stars are bright enough to support segment control ○ And are not necessarily near targets 5 Background: Why satellite LGS? ● LUVOIR segment stability must be ~picometers for exoplanet imaging ○ Hard/expensive/impossible(?) to build ● Not many natural guide stars are bright enough to support segment control ○ And are not necessarily near targets ● A formation-flying CubeSat with laser transmitter is bright enough…optical requirements established in Douglas et al. 2019 [1]. 6 One possible architecture [1] 7 Approach: Spacecraft design fits in 12U Propulsion Power 34 cm Laser Avionics ADCS W Kammerer and 22 cm 22 cm J Clark (MIT) 8 Results: How many LGSs? ● Electric propulsion minimizes the needed LGS constellation size. -

How Astronomical Objects Are Named

How Astronomical Objects Are Named Jeanne E. Bishop Westlake Schools Planetarium 24525 Hilliard Road Westlake, Ohio 44145 U.S.A. bishop{at}@wlake.org Sept 2004 Introduction “What, I wonder, would the science of astrono- use of the sky by the societies of At the 1988 meeting in Rich- my be like, if we could not properly discrimi- the people that developed them. However, these different systems mond, Virginia, the Inter- nate among the stars themselves. Without the national Planetarium Society are beyond the scope of this arti- (IPS) released a statement ex- use of unique names, all observatories, both cle; the discussion will be limited plaining and opposing the sell- ancient and modern, would be useful to to the system of constellations ing of star names by private nobody, and the books describing these things used currently by astronomers in business groups. In this state- all countries. As we shall see, the ment I reviewed the official would seem to us to be more like enigmas history of the official constella- methods by which stars are rather than descriptions and explanations.” tions includes contributions and named. Later, at the IPS Exec- – Johannes Hevelius, 1611-1687 innovations of people from utive Council Meeting in 2000, many cultures and countries. there was a positive response to The IAU recognizes 88 constel- the suggestion that as continuing Chair of with the name registered in an ‘important’ lations, all originating in ancient times or the Committee for Astronomical Accuracy, I book “… is a scam. Astronomers don’t recog- during the European age of exploration and prepare a reference article that describes not nize those names. -

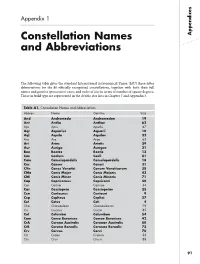

Constellation Names and Abbreviations Abbrev

09DMS_APP1(91-93).qxd 16/02/05 12:50 AM Page 91 Appendix 1 Constellation Names Appendices and Abbreviations The following table gives the standard International Astronomical Union (IAU) three-letter abbreviations for the 88 officially recognized constellations, together with both their full names and genitive (possessive) cases,and order of size in terms of number of square degrees. Those in bold type are represented in the double star lists in Chapter 7 and Appendix 3. Table A1. Constellation Names and Abbreviations Abbrev. Name Genitive Size And Andromeda Andromedae 19 Ant Antlia Antliae 62 Aps Apus Apodis 67 Aqr Aquarius Aquarii 10 Aql Aquila Aquilae 22 Ara Ara Arae 63 Ari Aries Arietis 39 Aur Auriga Aurigae 21 Boo Bootes Bootis 13 Cae Caelum Caeli 81 Cam Camelopardalis Camelopardalis 18 Cnc Cancer Cancri 31 CVn Canes Venatici Canum Venaticorum 38 CMa Canis Major Canis Majoris 43 CMi Canis Minor Canis Minoris 71 Cap Capricornus Capricorni 40 Car Carina Carinae 34 Cas Cassiopeia Cassiopeiae 25 Cen Centaurus Centauri 9 Cep Cepheus Cephei 27 Cet Cetus Ceti 4 Cha Chamaeleon Chamaeleontis 79 Cir Circinus Circini 85 Col Columba Columbae 54 Com Coma Berenices Comae Berenices 42 CrA Corona Australis Coronae Australis 80 CrB Corona Borealis Coronae Borealis 73 Crv Corvus Corvi 70 Crt Crater Crateris 53 Cru Crux Crucis 88 91 09DMS_APP1(91-93).qxd 16/02/05 12:50 AM Page 92 Table A1. Constellation Names and Abbreviations (continued) Abbrev. Name Genitive Size Cyg Cygnus Cygni 16 Appendices Del Delphinus Delphini 69 Dor Dorado Doradus 7 Dra Draco -

Space-Based Laser Guide Star Mission to Enable Ground and Space Telescope Observations of Faint Objects

Space-Based Laser Guide Star Mission to Enable Ground and Space Telescope Observations of Faint Objects Kerri Cahoy, James Clark, Gregory Allan, Yinzi Xin Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139; (617) 253-8541 [email protected], [email protected] Ewan Douglas, Jennifer Lumbres, Jared Males University of Arizona [email protected] ABSTRACT We present the detailed design of a Laser Guide Star small satellite that would formation fly with a large space observatory or fly with respect to a ground telescope that use adaptive optics (AO) for wavefront sensing and control. Using the CubeSat form factor for the Laser Guide Star small satellite, we develop a 12U system to accommodate a propulsion system. The propulsion system enables the LGS satellite to formation fly near the targets in the telescope boresight and to meet mission requirements on number of targets and duration. We simulate the formation flight at L2 to assess the precision required to enable the wavefront sensing and control during observation. We describe a design reference mission (DRM) for deploying 18 Laser Guide Stars to L2 to assist the Large Ultraviolet, Optical, Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR). The L2 LGS DRM covers over 250 exoplanet target systems with 5 or more revisits to each system over a 5-year mission using eighteen 12U CubeSats. We present a design reference mission for a laser guide star satellite to geostationary orbit for use with 6.5+ meter ground telescopes with AO to look at HD 50281, HD 180617, and other near-equatorial targets. -

Visual/Infrared Interferometry of Orion Trapezium Stars: Preliminary

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 6965 c ESO 2018 October 5, 2018 Visual/infrared interferometry of Orion Trapezium stars: Preliminary dynamical orbit and aperture synthesis imaging of the θ1Orionis C system S. Kraus1, Y. Y. Balega2, J.-P. Berger3, K.-H. Hofmann1, R. Millan-Gabet4, J. D. Monnier5, K. Ohnaka1, E. Pedretti5, Th. Preibisch1, D. Schertl1, F. P. Schloerb6, W. A. Traub7, and G. Weigelt1 1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, D-53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Special Astrophysical Observatory, Russian Academy of Sciences, Nizhnij Arkhyz, Zelenchuk region, Karachai-Cherkesia, 357147, Russia 3 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Grenoble, UMR 5571 Universit´eJoseph Fourier/CNRS, BP 53, F-38041 Grenoble Cedex 9, France 4 Michelson Science Center, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5 Astronomy Department, University of Michigan, 500 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104, USA 6 Department of Astronomy, University of Massachusetts, LGRT-B 619E, 710 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02183, USA Received December 19, 2006; accepted February 7, 2007 ABSTRACT Context. Located in the Orion Trapezium cluster, θ1Ori C is one of the youngest and nearest high-mass stars (O5-O7) and known to be a close binary. Aims. By tracing its orbital motion, we aim to determine the orbit and dynamical mass of the system, yielding a characterization of the individual components and, ultimately, also new constraints for stellar evolution models in the high-mass regime. Methods. Using new multi-epoch visual and near-infrared bispectrum speckle interferometric observations obtained at the BTA 6 m telescope, and IOTA near-infrared long-baseline interferometry, we traced the orbital motion of the θ1Ori C components over the interval 1997.8 to 2005.9, covering a significant arc of the orbit. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism.