Surf Tour.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. ARTISANAL FISHERIES There Is No Universal Definition of “Artisanal Fisheries” but Common Criteria (SEAFDEC 1999) Include 1

ACIAR Project FIS/2001/079 5. ARTISANAL FISHERIES There is no universal definition of “artisanal fisheries” but common criteria (SEAFDEC 1999) include 1. Small scale and often decentralized operations, 2. A predominance of small vessels (often <10 GT), 3. A predominance of traditional fishing gears (but may include trawl, seine, gill-net, and longline vessels), 4. Fishing trips are generally short and inshore, and 5. The fisheries are often largely subsistence fisheries, but there may be some commercial component. The ports surveyed for the artisanal component of this report only meet these criteria to varying degrees, with some being home to many vessels >10 GT, and with centralized commercial operations. However, for the purposes of this study, “artisanal ports” includes not only the smallest scale of landing place at the fishing village level (i.e. what most readers would consider truly artisanal), but also these larger landing places where fishing vessels are primarily owned by fishing households, but not by fishing companies, and where the majority of vessels are smaller than 25 GT. A summary of key features of the artisanal landing places surveyed are shown in Table 5.0.1. More detailed descriptions are provided in the sections that follow. 5.1 Bungus – Padang, Pariaman, and Painan (West Sumatra) There are 5 provinces on the west coast of Sumatra – from north to south, the provinces of Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam (formerly Daerah Istimewa Aceh), North Sumatra (Sumatra Utara), West Sumatra (Sumatra Barat), Bengkulu, and Lampung. Numerous islands are located off this coast - Banyak Archipelago islands in the north, Nias Island, Tanahmasa and Tanahbala Islands, the Mentawai Islands (that include Siberut, Sipura and Pagai Islands), and Enggano Island in the south. -

Download This PDF File

Kemanan Dalam Wisata Bahari (Penyelaman dan Surfng) : Tinjauan Permen Pariwisata R.I. No. 3 Tahun 2018 KEAMANAN DALAM WISATA BAHARI (PENYELAMAN DAN SURFING): TINJAUAN PERMEN PARIWISATA R.I. NO.3 TAHUN 2018 Muhamad Ali Muchlis Staf Pengajar Akademi Pariwisata Jakarta [email protected] Abstract Indonesia has many places for diving and surfing. Indonesia is a paradise for tourists to do diving and surfing. The problem then is legal protection for these activities. In 2018 the Minister of Tourism Decree No.3 has accommodated tourism activities for diving and surfing, this will increase protection for tourists. With maximum tourism equipment and management in the field of diving tourism and surfing tourism, it is expected that an increase in the area of tourist visits or tourist destinations and can benefit the community and the country and ensure the preservation of nature. Keywords: marine tourism, diving, surfing, accommodation, legal protection. I. Pendahuluan Indonesia adalah nusa-antara wilayah dengan pulau-pulau besar dan kecil di antara Samudera Hindia dan Samudera Pasifik dengan wilayah darat sebagai rangkaian pegunungan api yang memiliki keragaman geografis dan kaya akan sumber daya alam. Keindahan alam Indonesia memang tiada tara. Sebagai bangsa bahari Indonesia mewarisi taman laut yang menakjubkan, antara lain: Bunaken, Wakatobi, dan Raja Ampat yang menyimpan kekayaan terumbu karang dunia. Di Kawasan Raja Ampat terdapat lebih dari 1.070 jenis spesies ikan, 600 jenis spesies terumbu karang, dan 66 jenis molusca. Selain Kawasan Raja Ampat, Indonesia juga memiliki Laut Sulawesi yang masih penuh misteri, karena ditemukannya ikan Coelacanth yang diduga sudah punah 65 juta tahun yang lalu. Indonesia mewarisi kekayaan pantai yang beragam, pantai dengan pasir putih, pasir coklat, pasir hitam, pantai berpasir pink seperti di Pink Beach Pulau Komodo. -

From Nias Island, Indonesia 173-174 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft Für Herpetologie E.V., Wien, Austria, Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2004 Band/Volume: 16_3_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kuch Ulrich, Tillack Frank Artikel/Article: Record of the Malayan Krait, Bungarus candidus (LINNAEUS, 1758), from Nias Island, Indonesia 173-174 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at SHORT NOTE HERPETOZOA 16 (3/4) Wien, 30. Jänner 2004 SHORT NOTE 173 KHAN, M. S. (1997): A report on an aberrant specimen candidus were also reported from the major of Punjab Krait Bungarus sindanus razai KHAN, 1985 sea ports Manado and Ujungpandang in (Ophidia: Elapidae) from Azad Kashmir.- Pakistan J. Zool., Lahore; 29 (3): 203-205. KHAN, M. S. (2002): A Sulawesi (BOULENGER 1896; DE ROOIJ guide to the snakes of Pakistan. Frankfurt (Edition 1917). It remains however doubtful whether Chimaira), 265 pp. KRÀL, B. (1969): Notes on the her- current populations of kraits exist on this petofauna of certain provinces of Afghanistan.- island, and it has been suggested that the Zoologické Listy, Brno; 18 (1): 55-66. MERTENS, R. (1969): Die Amphibien und Reptilien West-Pakistans.- records from Sulawesi were the result of Stuttgarter Beitr. Naturkunde, Stuttgart; 197: 1-96. accidental introductions by humans, or MINTON, S. A. JR. (1962): An annotated key to the am- based on incorrectly labeled specimens phibians and reptiles of Sind and Las Bela.- American Mus. Novit., New York City; 2081: 1-60. MINTON, S. (ISKANDAR & TJAN 1996). A. JR. (1966): A contribution to the herpetology of Here we report on a specimen of B. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

Seismic Tomographic Imaging of P Wave Velocity Perturbation Beneath Sumatra, Java, Malacca Strait, Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore

J. Earth Syst. Sci. (2021) 130:23 Ó Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-020-01530-w (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-vol V) Seismic tomographic imaging of P wave velocity perturbation beneath Sumatra, Java, Malacca Strait, Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore 1, 2 ABEL UYIMWEN OSAGIE * and ISMAIL AHMAD ABIR 1Department of Physics, University of Abuja, P.M.B 117, Abuja, Nigeria. 2School of Physics, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Pulau Penang, Malaysia. *Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] MS received 6 March 2020; revised 20 July 2020; accepted 24 October 2020 P wave tomographic imaging of the crust down to a depth of 90 km is performed beneath the region encompassing Sumatra, Java, Malacca Strait, peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Inversion is performed with 99,741 Brst-arrival p waves from 16,196 local and regional earthquakes occurred around the Sumatra Subduction Zone (SSZ) between 1964 and 2018. Tomographic results show low-velocity (low-V) anomalies that reCect both accretion and possibly, asthenospheric upwelling associated with subduction of the Australian Plate beneath Eurasia around the SSZ. The prominent low-V anomaly is thickest around the Conrad, extending beneath Straits of Malacca and parts of peninsular Malaysia, but disap- pears around the Moho in the region. Below the Moho, the subducting slab, represented by a high-velocity (high-V) anomaly, trends in the orientation of Sumatra. At these depths, the eastern shorelines of Sumatra, most parts of Malacca Strait and the west coast of peninsular Malaysia show varying degrees of positive velocity anomalies. We consider that asthenospheric upwelling around the SSZ may provide heat source for the 40 or more hot springs distributed north–south in peninsular Malaysia. -

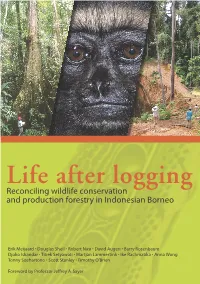

Life After Logging: Reconciling Wildlife Conservation and Production Forestry in Indonesian Borneo

Life after logging Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard • Douglas Sheil • Robert Nasi • David Augeri • Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar • Titiek Setyawati • Martjan Lammertink • Ike Rachmatika • Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono • Scott Stanley • Timothy O’Brien Foreword by Professor Jeffrey A. Sayer Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard Douglas Sheil Robert Nasi David Augeri Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar Titiek Setyawati Martjan Lammertink Ike Rachmatika Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono Scott Stanley Timothy O’Brien With further contributions from Robert Inger, Muchamad Indrawan, Kuswata Kartawinata, Bas van Balen, Gabriella Fredriksson, Rona Dennis, Stephan Wulffraat, Will Duckworth and Tigga Kingston © 2005 by CIFOR and UNESCO All rights reserved. Published in 2005 Printed in Indonesia Printer, Jakarta Design and layout by Catur Wahyu and Gideon Suharyanto Cover photos (from left to right): Large mature trees found in primary forest provide various key habitat functions important for wildlife. (Photo by Herwasono Soedjito) An orphaned Bornean Gibbon (Hylobates muelleri), one of the victims of poor-logging and illegal hunting. (Photo by Kimabajo) Roads lead to various impacts such as the fragmentation of forest cover and the siltation of stream— other impacts are associated with improved accessibility for people. (Photo by Douglas Sheil) This book has been published with fi nancial support from UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio. The authors are responsible for the choice and presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of CIFOR, UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio and do not commit these organisations. -

Numerical Study of Tsunami Propagation in Mentawai Islands West Sumatra

Universal Journal of Geoscience 5(4): 112-116, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujg.2017.050404 Numerical Study of Tsunami Propagation in Mentawai Islands West Sumatra Noverina Alfiany*, Kazuhiro Yamamoto, Masaji Watanabe Graduate School of Environmental and Life Science, Okayama University, Japan Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Shallow water equations were analyzed available from U.S Geological website. Satake, et. al [2] numerically for simulation of tsunami propagation from the computed 25th, October 2010, Mentawai Islands coastal source area to coastal zone of Mentawai Islands along West tsunami heights from the tsunami source model which was Sumatra Island. A triangular mesh was set for spatial proposed from a field survey and waveform recording with discretization and a system of partial differential equation is linear equations. The slip distributions on the fault planes reduced to a system of ordinary differential equations. were estimated through the inversion of tsunami waveform, Initial displacement based on Okada model was applied. whereas the strikes and rakes were estimated from USGS W Our numerical techniques were demonstrated with a phase solution. simulation of tsunami generated from an earthquake with In this study the propagation of tsunami waves generated epicenter near South Pagai Island, Mentawai Islands, in Mentawai Islands segment were studied numerically. A Indonesia. triangular mesh was employed for discretization of the governing equations, a system of partial differential Keywords Tsunami Simulation, Okada Model, Finite equations, to a system of ordinary differential equations. -

M7.2 Offshore Padang, Sumatra, Indonesia Earthquake of 25 February 2008 Network

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR EARTHQUAKE SUMMARY MAP XXX U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with the Global Seismographic M7.2 offshore Padang, Sumatra, Indonesia Earthquake of 25 February 2008 Network Tectonic Setting Epicentral Region 90° 100° 110° 120° 94° 96° 98° 100° 102° 104° 1E99X0PLANATION T H A I L A N D 1935 Ipoh Mag ≥ 7.0 V I E T N A M P h i l i p p i n e F a u l t Kemaman Harbor C A M B O D I A 0 - 69 km Kuala Lipis B A Y O F 1916 B E N G A L 1941 P H I L I P P7I0N E- S299 4° 4° 1936 DiamondK uBaanrt aann Nd eCwh Pinoort Hills A N D A M A N 300 - 600 M a l a y s i a S E A Gulf 1948 10° of 10° 1976 Medan Thailand 25 February 2008 8:36:35 UTC BURMA 1881 Rupture Zones N PLATE A W H A G 1955 Kuala Lumpur 2.351° S., 100.018° E. S R I L A N K A L U Year of Earthquake A O Shah Alam P R Depth 35 km T 2005 Mw = 7.2 (USGS) SUNDA PLATE 2008 2004 Seremban B R U N E I Felt throughout the Los Angeles Basin area and in much M of southern California. Felt as far away as Las Vegas, A C e l e b e s 1941 2004 L Simeulue A S u m a t r a F a u l t B a s i n Nevada, and Yuma, Arizona. -

Seminar Proceeding

SEMINAR PROCEEDING International Seminar and Workshop on Hydrography Roles of Hydrography in Marine Industry and Resources Management Batam Island, 27-29 August 2013 CCoommmmiitttteeee Steering Committee Head of Geospatial Information Agency, Dr. Asep Karsidi, MSc Head of National Land Agency, Hendarman Supandji, S.H., M.H., C.N. Head of Hydro-Oceanographic Office, Laksma TNI Aan Kurnia, SSos Head of Indonesian Surveyor Association, Ir. Budhy Andono Soenhadi, MCP Head of Indonesian Hydrographic Society, Prof. Dr.-Ing. Sjamsir Mira Reviewer and Scientific Committee Prof. Dr. Widyo Nugroho SULASDI (Bandung Institute of Technology) Prof. Dr. Hasanuddin Z. Abidin (Bandung Institute of Technology) Prof. Dr. Razali Mahmud (University of Technology Malaysia-Malaysia) Prof. Dr.-Ing. Delf Egge (Hafen City University, Hamburg, Germany) Organizing Committee Chair : Dr. Ir. Samsul Bachri, M.Eng Co-chair : Ir. Tri Patmasari, MSi Finance : Sylvia Nayoan Secretary : Ir. Nanang Henky Suharto Co-secretary : Wiria Indraswari, SE Sponsorship : Ir. Fuad Fachrudin Publication : Ir. Syartoni Kamaruddin Security and Permit : Kol. Laut Daryanto : Letkol. Laut Nurriyadi Coordinator of Seminar : Dr.rer.nat. Wiwin Windupranata, ST., MSi Publication : Agung Pandi Nugroho, ST. Sella Lestari, ST, MT Design : Auzan Kasyfu Ambara Registration : Intan Hayatiningsih, ST, MSc Alifiya Ikhsani Apriliyana Coordinator of Exhibition : Renny Rachmalia, ST. Coordinator of Workshop : Kol. Laut. Trismadi Co-coordinator : Drs. Win Islamudin Bale Class Coordinator : Fajar Triady -

Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Myanmar, Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali

S An easy-to-use photographic identification guide covering 245 N snake species found in Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Myanmar, AK Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali. • Authoritative text describes identifying features, distribution, E habits and habitat with boxed features introducing snake families S • Length, common and scientific names plus vernacular names listed O • Introduction includes venom data, snake topography to permit F rapid field identification of each species covered and glossary T • Includes an up-to-date checklist of the snakes of Southeast Asia, HA with their current global conservation status I LA ND & S & O U T nd H 2 EDITION E A NATURALIST’S GUIDE TO THE AS T AS SNAKES Indraneil Das is Professor of Herpetology at Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. He has a DPhil from Oxford University and was a Fulbright Postdoctoral OF I Fellow at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. He has A authored many books on snakes. I ndraneil THAILAND & SOUTHEAST ASIA Indraneil Das D as NATURAL HISTORY/HERPETOLOGY ISBN 978-1-912081-92-9 NEPAL BHUTAN CHINA Ryukyu INDIA BANGLADESH Islands Taipei MYANMAR TAIWAN VIETNAM (BURMA) Hong Kong Bay LAOS of Hainan PHILIPPINE Bengal Yangon Luzon THAILAND SEA SOUTH PACIFIC Andaman Bangkok Manila PHILIPPINES Islands CAMBODIA CHINA Mindoro OCEAN SEA Samar Phnom Ho Chi Panay Leyte Penh Minh Palawan Nicobar Negros Islands Mindanao Palau Mantanani Banggi Davao Malay MALAYSIA BRUNEI Peninsula Sabah Natuna CELEBESTalaud Islands Medan Kuala Lumpur Islands Sarawak SEA Singapore Halmahera Kalimantan Sula -

Magnitude 7.7 Earthquake Generates Local Tsunami Off Western Sumatra

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State [email protected] Indonesia: Magnitude 7.7 Earthquake Generates Local Tsunami http://hiu.state.gov HUMANITARIAN INFORMATION UNIT off Western Sumatra (October 25, 2010, 14:42 UTC) \! Kuala Lumpur \ National capital Earthquake - Tsunami Simeulue « Provincial capital On October 25, 2010, at 14:42 UTC, a magnitude 7.7 earthquake Province boundary MALAYSIA hit the Kepulauan Mentawai Region in western Sumatra, Earthquake epicenter (M 7.7) generating a tsunami; as of 22:30 UTC there had been twelve D Sumatra aftershocks,including two greater than magnitude 6.0. The Utara epicenter of the Pulau Pagai Selatan earthquake was: # Aftershocks greater than M 4.0 tLN NJMFT XFTUPGQSPWJODJBMDBQJUBM Expected Shaking Intensity Nias \! Bengkulu (309,700 people); Strong SINGAPORE tLN NJMFT TPVUIPGQSPWJODJBMDBQJUBM1BEBOH Moderate (860,000 people). Light Estimated Population Density !«Pekanbaru Seven minutes after the earthquake, the Pacific Tsunami (persons per sq. km) Warning Center at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Fewer than 5 Administration issued a local tsunami warning. The Mentawai Riau 5 - 50 Sumatra Islands experienced 10-foot waves as far as 2,000 feet inland. 51 - 500 Barat One year ago, in September 2009, Western Sumatra was hit by a 501 - 50,000 powerful earthquake of 7.9 magnitude, which killed more than Greater than 50,000 1,000 people and caused massive infrastructure damage. !«Padang Siberut Current Situation (as of October 27, 15:30 UTC) Jambi!« Jambi t0WFSEFBUITBSFDPOöSNFECZUIF8FTU4VNBUSB KEPALUAN provincial disaster management office. MENTAWAI Sipura t"QQSPYJNBUFMZGBNJMJFTFWBDVBUFEUPIJHIFSHSPVOEBOE ISLANDS 412 people are reported still missing. # t0WFS QFPQMFJOUIFBSFBSFQPSUFEMZTPVHIUTIFMUFSJO Pagi Utara emergency camps. # # M 6.2 t)FBWZSBJOJTQSFWFOUJOHIFMJDPQUFSTGSPNSFBDIJOHUIFBSFB # Pagi # # Selatan Sumatra t-PDBMMZTJUVBUFEOPOHPWFSONFOUBMPSHBOJ[BUJPO4VSGBJE # # Bengkulu Selatan reported public telecommunications are down. -

Odonata: Chlorocyphidae)

Zootaxa 4079 (4): 495–500 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4079.4.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:18895002-F0ED-45EE-A01A-919A7529C6D8 Description of Heliocypha vantoli spec. nov. from Siberut in the Mentawai Islands (Odonata: Chlorocyphidae) MATTI HÄMÄLÄINEN Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA, Leiden, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Heliocypha vantoli Hämäläinen, spec. nov. [holotype ♂ from Indonesia, Mentawai Islands (off Sumatra), Siberut Island, 29-31 January 2013, deposited at RMNH, Leiden, The Netherlands] is described and illustrated for both sexes and compared with the Heliocypha species found in Sumatra and adjacent small islands. Notes on the Odonata fauna of the Mentawai Islands are also provided. Euphaea aspasia Selys, 1853 (Euphaeidae) is recorded as new to these islands; dif- ferences in the colour pattern of the Siberut and mainland Sumatran specimens are briefly discussed. Key words: Odonata, Chlorocyphidae, Heliocypha, new species, Siberut, Mentawai, Sumatra Introduction Surprisingly little has been published on the dragonflies of Sumatra and its satellite islands since the mid 1950’s. Previously, numerous important papers had been published by various authors, starting with those by Albarda (1887) and Selys Longchamps (1889). The most recent synopsis of the Sumatran fauna is to be found in Lieftinck’s (1954) handlist of the Sundaland Odonata, which lists a total of 15 species and one subspecies of Chlorocyphidae from the mainland Sumatra and the adjacent small islands off its western coast.