The World Bank for OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report, Which, with the Suggestions and Inputs of the Members of the Technical Committee of KEA and the Internal Assessor of KEA, Was Modified

PREFACE Karnataka is a State that has a long and diverse history exhibiting itself in the historic caves, forts, places of worship and palaces and through arts and artifacts preserved in museums. If history is to be conserved for the generations to come; historic places, monuments and museums need to be conserved. The conservation of historic structures and sites is guided by the tenet of minimum intervention and retention of original fabric, so that no information that it provides to the viewer/academician is lost. Funds provided under the 12th Finance Commission were utilized by the Department of Archeology, Museums and Heritage of the Government of Karnataka to conserve historic structures, sites and museums in Karnataka. An evaluation of this work was entrusted by the Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department of Government of Karnataka to Karnataka Evaluation Authority (KEA). The KEA outsourced this study to READI-INDIA, Dharwad. They completed the evaluation and presented their report, which, with the suggestions and inputs of the members of the Technical Committee of KEA and the Internal Assessor of KEA, was modified. The final report is before the reader. The most satisfying finding of the evaluation study has been that the work of conservation of historic monuments and sites has been done in an appropriate manner (least intervention) by the department. In the course of the study, from the findings and recommendations the following main points have emerged- (i) The declaration of any building as “heritage buildi ng” should be done by the Department of Archeology, Museums and Heritage and not by the local authority under the Karnataka Town and Country Planning Act, 1961. -

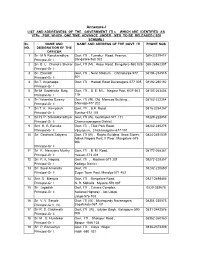

Annexure-I LIST and ADDRESSESS of the GOVERNMENT ITI S WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS Vtps for WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES to BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL

Annexure-I LIST AND ADDRESSESS OF THE GOVERNMENT ITI s WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS VTPs FOR WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES TO BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL. NAME AND NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE GOVT. ITI PHONE NOS NO. DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICER 1 Sri M N Renukaradhya Govt. ITI , Tumakur Road, Peenya, 080-23379417 Principal-Gr I Bangalore-560 022 2 Sri B. L. Chandra Shekar Govt. ITI (M) , Hosur Road, Bangalore-560 029 080-26562307 Principal-Gr I 3 Sri Ekanath Govt. ITI , Near Stadium , Chitradurga-577 08194-234515 Principal-Gr II 501 4 Sri T. Anjanappa Govt. ITI , Hadadi Road Davanagere-577 005 08192-260192 Principal-Gr I 5 Sri M Sadathulla Baig Govt. ITI , B. E. M.L. Nagara Post, KGF-563 08153-263404 Principal-Gr I 115 6 Sri Yekantha Swamy Govt. ITI (W), Old Momcos Building, , 08182-222254 Principal-Gr II Shimoga-577 202 7 Sri T. K. Kempaiah Govt. ITI , B.H. Road, 0816-2254257 Principal-Gr II Tumkur-572 101 8 Sri H. P. Srikanataradhya Govt. ITI (W), Gundlupet-571 111 08229-222853 Principal-Gr II Chamarajanagara District 9 Smt K. R. Renuka Govt. ITI , Tilak Park Road, 08262-235275 Principal-Gr II Vijayapura, Chickamagalur-577 101 10 Sri Giridhara Saliyana Govt. ITI (W) , Raghu Building Urwa Stores, 0824-2451539 Ashok Nagara Post, II Floor, Mangalore-575 006. Principal-Gr II 11 Sri K. Narayana Murthy Govt. ITI , B. M. Road, 08172-268361 Principal-Gr II Hassan-573 201 12 Sri P. K. Nagaraj Govt. ITI , Madikeri-571 201 08272-228357 Principal-Gr I Kodagu District 13 Sri Syed Amanulla Govt. -

Educational Profile of Karnataka

Educational Profile of Karnataka : As of March 2013, Karnataka had 60036 elementary schools with 313008 teachers and 8.39 million students, and 14195 secondary schools with 114350 teachers and 2.09 million students. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnataka - cite_note-school-99 There are three kinds of schools in the state, viz., government-run, private aided (financial aid is provided by the government) and private unaided (no financial aid is provided). The primary languages of instruction in most schools are Kannada apart from English, Urdu and Other languages. The syllabus taught in the schools is by and large the state syllabus (SSLC) defined by the Department of Public Instruction of the Government of Karnataka, and the CBSE, ICSE in case of certain private unaided and KV schools. In order to provide supplementary nutrition and maximize attendance in schools, the Karnataka Government has launched a mid-day meal scheme in government and aided schools in which free lunch is provided to the students. A pair of uniforms and all text books is given to children; free bicycles are given to 8th standard children. Statewide board examinations are conducted at the end of the period of X standard and students who qualify are allowed to pursue a two-year pre-university course; after which students become eligible to pursue under-graduate degrees. There are two separate Boards of Examination for class X and class XII. There are 652 degree colleges (March 2011) affiliated with one of the universities in the state, viz. Bangalore University, Gulbarga University, Karnataka University, Kuvempu University, Mangalore University and University of Mysore . -

State Educational Profile. Karnataka.Pdf

STATE EDUCATIONAL PROFILE As of March 2013, Karnataka had 60036 elementary schools with 313008 teachers and 8.39 million students, and 14195 secondary schools with 114350 teachers and 2.09 million students. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnataka - cite_note-school-99 There are three kinds of schools in the state, viz., government-run, private aided (financial aid is provided by the government) and private unaided (no financial aid is provided). The primary languages of instruction in most schools are Kannada apart from English, Urdu and Other languages. The syllabus taught in the schools is by and large the state syllabus (SSLC) defined by the Department of Public Instruction of the Government of Karnataka, and the CBSE, ICSE in case of certain private unaided and KV schools. In order to provide supplementary nutrition and maximize attendance in schools, the Karnataka Government has launched a mid-day meal scheme in government and aided schools in which free lunch is provided to the students. A pair of uniforms and all text books is given to children; free bicycles are given to 8th standard children. Statewide board examinations are conducted at the end of the period of X standard and students who qualify are allowed to pursue a two-year pre-university course; after which students become eligible to pursue under-graduate degrees. There are two separate Boards of Examination for class X and class XII. There are 652 degree colleges (March 2011) affiliated with one of the universities in the state, viz. Bangalore University, Gulbarga University, Karnataka University, Kuvempu University, Mangalore University and University of Mysore . -

Sample 11361.Pdf

Strictly as per the latest syllabus prescribed by Department of Pre-University Education, Karnataka For 2018 Exam KARNATAKA II PUC CHAPTERWISE / TOPICWISE SOLVED pAPERS 2011 - 2017 With Topper’s A nswers of 2016 Exam CLASS 12 History To Buy These Books Visit Bangalore Division P:9742118458 • MirJamidar Book Depot P: 9449974186 • M.S. Gudedinni & Sons P .:(08352) 250970 BANGALORE • Shubham Book & Stationers P.: (080) 23638641 DHARWAD • Kulkarni Book Stall & Staioners P: (0836) 2748720, • Avenue Book Centre P. (080)22244753, 9341254836 9480083720 • Praksh Pustakalaya P: 8362435026 • Balaji Book Centre P.:(080) 23331259 • Book Palace • Ravi Praveen Pustakalaya P: 9945362492 • Bharat P. : ( 0 8 0 ) 2 2 4 4 0 9 7 2 • H e m a B o o k W o r l d Book Depot Ph.: 9445506375 • Akal Wadi Book Depot P.: 9945731121 • Karnataka Book Depot P.: (080) P: 09449826211 22291832, 9844350378 • Maharana Agencies GADAG • Sri Rajeshwari Vidya Niketan P. : (08372) 289057 P.: (080) 23472295, 9448253433 • Manasi Stationers P.: (080) 28560186, 9480019745 • Maruti Book Centre HONAVAR • Shivani Trade Corporation P.: 9448132155 P.: (080) 40124558, 9663777175 • Sapna Book House HUBLI • Ajay Agencies P.: (0836) 2216394, 9342136251 P.: (080) 40114455, 22266088 • Saraswati Book Centre • Pragati Books & Stationers P.: 9449419550 • V i j a y P.: (080)2315201, 9845351101 • Sri Balaji Books & Book Centre P.: (0836) 4258401, 9342905801 • Renuka Stationers P.: 8022117659 • Sri Balaji Store P.:(080) Book Depot P.: (0836) 4257624 • Prakash Book Agencies 28461970, 9845731754 • Sri -

(Admn) DVO, Commercial Tax Department, Behind Old Bus Stand, Near Railway Station, Gulbarga.-585 102

GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA COMMERCIAL TAXES DEPARTMENT Joint Commissioner of Commercial Taxes. (Admn) DVO, Commercial Tax Department, Behind Old Bus stand, Near Railway Station, Gulbarga.-585 102 No. JCCT/(Admn)/GLB/EST/10-11/ Dated: 07-09-2010 TENDER NOTIFICATION Tenders are invited under two cover system, for providing services of Eight(08) Data Entry Operators for making entries of cheques, VAT returns and other works in the offices of the Commercial Taxes Department (CTD) located in Gulbarga Division. The prescribed tender forms and the Request for Proposal (RFP) showing terms and conditions and other relevant details can be obtained from the office of the undersigned during office hours on all working days on payment of Rs.200/-+13.5% VAT i.e., total Rs. 227/-(not refundable).Last date for issue of tender forms is 15-09-2010 up to 5.30 p.m. The bidder should satisfy all the terms and conditions laid down in the RFP in relation to providing the said Data Entry Operators. The first cover in respect of the technical bid should contain : 1. The Technical / Pre-qualification bid with all the required details in the prescribed format (Annexure-I) appended to the RFP 2. PAN details under the Indian Income Tax Act, 1961 3. Proof to show that the bidder has its Head Office in Karnataka and has been operating for the last 3 years in the State of Karnataka in providing Data Entry Operators. The 1st sealed cover should be super scribed with the words" Technical / Pre-qualification bid for providing Data Entry Operators at Gulbarga. -

Issn: 2278-6236 Multi Dimension Strategy for the Development of the Hyderabad Karnataka Region Introduction

` International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 MULTI DIMENSION STRATEGY FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HYDERABAD KARNATAKA REGION Dr. Ravindranath N. Kadam, Associate Professor, Dept. of Studies & Research in Economics, Kuvempu University, Shankaraghatta, Shivamogga Dist, Karnataka State, India Abstract: The sub continent, India has diversity in many respects. No doubt all the states in the country are not even in all respects. No all regions are similar and equally developed. The different Finance Commissions and the Planning commission laid stress on the objective of achieving evenhanded regional development. In Karnataka state also all the regions are not equally treated and developed. It is quite essential to maintain the equality in most of the aspects. Recently the government of Karnataka has opened eyes and showing interest in the development of backward regions of Karnataka. The development of Hyderabad Karnataka (Gulbarga Division) is to be achieved on priority base as it has been neglected by the earlier rulers (Hyderabad Nizam). The present Hyderabad Karnataka region includes Bellary, Bidar, Gulbarga, Koppal and Raichur districts. The Hyderabad Karnataka region is situated in the North-Eastern part of Karnataka and bonded with Maharashtra on the North and Andhra Pradesh on the East and South. The climate of the Hyderabad Karnataka region comprised with dryness for the major part of the year and has very hot summer and scanty rain fall. In this paper attempt is made to highlight the resources available in the Hyderabad Karnataka region and the new avenues possible for the development of the region. -

GULBARGA (Karnataka)

A BASELINE SURVEY OF MINORITY CONCENTRATION DISTRICTS OF INDIA GULBARGA (Karnataka) Sponsored by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India and Indian Council of Social Science Research INSTITUTE FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT NIDM Building, IIPA Campus, I.P. Estate Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110002 Tel: 23358166, 23321610 / Fax: 23765410 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www. ihdindia.org 2008 A BASELINE SURVEY OF MINORITY CONCENTRATION DISTRICTS OF INDIA GULBARGA (Karnataka) Sponsored by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India and Indian Council of Social Science Research INSTITUTE FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT NIDM Building, IIPA Campus, I.P. Estate Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110002 Tel: 23358166, 23321610 / Fax: 23765410 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www. ihdindia.org RESEARCH TEAM Principal Researchers Alakh N. Sharma Ashok K. Pankaj Data Processing and Tabulation Balwant Singh Mehta Sunil Kumar Mishra Abhay Kumar Research Associates/Field Supervisors Ramashray Singh Ashwani Kumar Subodh Kumar M. Poornima Research Assistant P.K. Mishra Secretarial Assistance Shri Prakash Sharma Nidhi Sharma Sindhu Joshi GULBARGA Principal Author of the Report Chaya Deogankar Senior Visiting Fellow Institute for Human Development CONTENTS Executive Summary......................................................................................................i-v Chapter I: Introduction ............................................................................................1-13 An Overview of Gulbarga District..................................................................................... -

State Forest Service DCF's

State Forest Service DCF's 1 Sri.Sabakath Hussain H C 2 Sri.Raju S P Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Dharwad Division, Dharwad. Yadgir Division, Yadgir. 3 Sri.Balachandra T 4 Dr.Dr. Shankara P Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Hunsur Division, Hunsur. Virajpet Division, Virajpet. 5 Sri.Yatish Kumar D 6 Sri.Dhananjaya S Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Yellapur Division, Yellapur. Bidar Division, Bidar. 7 Sri.Basavaraj V Patil 8 Dr.Rajashekaran P Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Belgaum Division, Belgaum. Davanagere Division, Davanagere. 9 Sri.Raghavendra K L 10 Sri. Narayana Murthy D C Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Ghataprabha Division, Gokak. Gulbarga Division, Gulbarga. 11 Sri. Aghore D N 12 Sri. Jagadish Deputy Conservator of Forests Deputy Conservator of Forests, Kolar Gadag Division, Gadag Division, Kolar. 13 Sri. Rajendra H J 14 Sri. Ganapathi D L Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Haveri Division, Haveri. Forest Mobile Squad, Shimoga. 15 Sri. Daulat Hussain P 16 Sri. Basavarajaiah Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Social Forestry, Gulbarga Wildlife Division, Shimoga. 17 Sri. Amaranath M V 18 Sri. Rajanna R Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests & Regional Tumkur Division, Tumkur. Director (Environment) Gulbarga. 19 Sri. Agnihotri G V 20 Sri. Prasanna Kumar T S Deputy Conservator of Forests Deputy Conservator of Forests & Technical Social Forestry, Dharwad. Assistant to Conservator of Forests, Working Plan, Chickmagalur. 21 Sri. Lakshman R N 22 Sri. Javed Mumtaz Deputy Conservator of Forests, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Social Forestry (Forest Research) Bangalore. -

Karnataka Department of Commercial Taxes

Government of Karnataka Department of Commercial Taxes PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMISSIONER OF COMMERCIAL TAXES (KARNATAKA), BANGALORE Present: Ritvik Pandey, IAS Commissioner of Commercial Taxes (Karnataka) Bangalore, Subject: Issue of territorial jurisdiction and jurisdiction of powers and functions under the Karnataka Goods and service Tax Act (Karnataka Act 27 of 2017) to the officers working at Intelligence and Vigilance Divisions in the State. Ref: 1) Order No. Adcom (I&C)JDN/CR-192/2015-16.dated: 02.04.2016. 2) Order No. Adcom (I&C)/JDN/Registration/CR-15/2017-18 dated 29.06.2017 Preamble: With reference to the subject above, a nationwide uniform tax is brought into effect from 01.07.2017 by Goods and Service Tax Act. In the State of Karnataka, the Karnataka Goods and Service Tax Act, 2017(Karnataka Act 27 of 2017) is in force. In order to verify whether the taxable persons have accounted the turnovers in their books of accounts, to prevent the evasion of tax on goods and services, to take up inspections of the business premises of taxable persons, conduct test purchases, checking of goods vehicles, checking of stocks, physical verification, to confiscate goods vehicles and goods and to enforce other statutory functions is necessary in the interest of collection of revenue under the Karnataka Goods and Service Act 2017 by all officers working in the Enforcement and Vigilance divisions in the State. Therefore, it is essential to assign the geographical jurisdiction and statutory powers to all the officers working in the Enforcement and Vigilance Divisions of the Department. 2. Accordingly, all pending cases of inspection of business premises under the presently repealed Acts prior to the introduction of Goods and Service Tax Act, 2017, by the enforcement and vigilance wing are required to be finalized exercising the powers provided under section 174 of the Karnataka Goods and Services Tax Act 2017. -

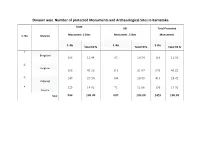

Division Wise Number of Protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka

Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka State ASI Total Protected S. No Division Monument / Sites Monument / Sites Monuments S. No S. No S. No Total TO % Total TO % Total TO % 1 Bangalore 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 2 Belgaum 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 3 249 29.50 164 26.93 413 28.42 Kalgurugi 4 125 14.81 71 11.66 196 13.51 Mysore Total 844 100.00 609 100.00 1453 100.00 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Bangalore Division Serial Per Total No. of Overall pre- Name of the District Number Total No. of cent Per protected protected ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected Monument / Sites % Sites monuments 1 Bangalore City 7 2 9 2 Bangalore Rural 9 5 14 3 Chitradurga 8 6 14 4 Davangere 8 9 17 5 Kolara 15 6 21 6 Shimoga 12 26 38 7 Tumkur 29 6 35 8 Chikkaballapur 4 2 6 9 Ramanagara 13 1 14 Total 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Belgaum Division Total No. of Overall pre- Serial Per Name of the District Total No. of Per protected protected Number cent ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected % Monument / Sites Sites monuments 10 Bagalkot 22 110 132 11 Belgaum 58 38 96 12 Vijayapura 45 96 141 13 Dharwad 27 6 33 14 Gadag 44 14 58 15 Haveri 118 12 130 16 Uttara Kannada 51 35 86 Total 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Kalburagi Division Serial Per Total protected -

Structural Growth and Development of Livestock Sector in North-Eastern Karnataka – an Economic Analysis§

Agricultural Economics Research Review Vol. 27 (No.2) July-December 2014 pp 319-325 DOI: 10.5958/0974-0279.2014.00036.6 Research Note Structural Growth and Development of Livestock Sector in North-Eastern Karnataka – An Economic Analysis§ B. Sserunjogi* and H. Lokesha Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, University of Agricultural Sciences, Raichur-584 104, Karnataka Abstract The growth trends in the livestock sector have been analyzed for Karnataka’s four divisions, viz. Gulbarga, Belgaum, Mysore and Bangalore, by using livestock census data of the state for the years 1977, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2003 and 2007. To explore the factors determining the growth of livestock sector, the Cobb Douglas function has been fitted. To study production of milk, meat and eggs in the state, data have been collected for the period 1995-96 to 2011-12. The cattle and buffalo population has depicted a declining trend, which in turn has affected production of milk, beef and carabeef in the state. The study has observed that poultry population and adoption of improved hen for egg production have tremendously increased across all the divisions in the state. The growth in the population of goat and sheep has been meagre. The production of pork has been highest, while mutton and chevon production has registered a dismal growth. The factors identified to limit the growth of livestock sector in the state include shortage of feed and fodder, inadequate breeding and reproduction, inadequate healthcare centres, poor public expenditure, poor flow of credit and lack of livestock insurance. The study has suggested some policy implications also.