GULBARGA (Karnataka)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employees Details (1).Xlsx

Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services, KALABURGI District Super Specialities ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Namdev Rathod Assistant Director 08472-226139 9480688435 Veterinary Hospital CompoundSedam Road Kalaburagi pin Cod- 585101 Veterinary Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. M.S. Gangnalli Assistant Director 08470-283012 9480688623 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 Assistant Director 2 Dr. Sanjay Reddy (Incharge) 08477-202355 94480688556 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Dhanaraj Bomma Assistant Director 08475-273066 9480688295 Veterinary Hospital Chincholi pincode: 585307 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi Assistant Director 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital opsite Railway Station Chittapur pincode: 585211 5 Dr. Raju B Deshmukh Assistant Director 08442-236048 9480688490 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Maruti Nayak Assistant Director 08441-276160 9449618724 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Mobile Veterinary Clinics ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Kimmappa Kote CVO 08470-283012 9449123571 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 2 Dr. sachin CVO 08477-202355 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Mallikarjun CVO 08475-273066 7022638132 Veterinary Hospital At post Chandaput Tq: chincholi pin code;585305 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi CVO 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital Chittapur 5 Dr. Subhaschandra Takkalaki CVO 08442-236048 9448636316 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Ashish Mahajan CVO 08441-276160 9663402730 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Veterinary Hospitals (Hobli) ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 3 | decembeR - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ “TOURISM IN HYDERABAD KARNATAKA REGION: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE” Dr. Aanjaneya Guest Faculty , Dept. of Economics , Government Womens Degree College , Old Jewargi Road Kalaburagi , Karnataka. ABSTRACT Tourism development is a priority for rural and regional areas of Hyderabad Karnataka Region. It’s considered to be economic bonanza for Hyderabad Karnataka districts because industrial development is very limited among six districts, being a labour –intensive industry the scope of employment is very vast. Hyderabad Karnataka is an area with great tourisms potential and provides immense business opportunity for backward region. The state is bestowed with beauty and rich of heritage monuments, ancient unidentified spots etc. Tourism is an industry capable of change the socio- cultural economic and environmental face of the world tourism is one of the largest and fastest growing industries in the world it has the potential to influence the living pattern of communities it is the collection of activities services and industries that deliver a travel experience including transportation, accommodation, eating and drinking establishments of retail shops, entertainment, business, and other hospitality services provided for individuals or groups of travelling from home. KEYWORDS: Potentiality, Tourist, Place, visitors, Development I. INTRODUCTION Tourism has become a phenomenon in both developed and developing economies across the globe, Tourism as a displacement activity, involves being away from home on a temporary short-term visit to and stay at places of interest outside one's domicile and work. United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) however put a time limit of within a year of stay outside the environment other than your home either for business, leisure or other purposes to the definition of tourism. -

Table of Content Page No's 1-5 6 6 7 8 9 10-12 13-50 51-52 53-82 83-93

Table of Content Executive summary Page No’s i. Introduction 1-5 ii. Background 6 iii. Vision 6 iv. Objective 7 V. Strategy /approach 8 VI. Rationale/ Justification Statement 9 Chapter-I: General Information of the District 1.1 District Profile 10-12 1.2 Demography 13-50 1.3 Biomass and Livestock 51-52 1.4 Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography 53-82 1.5 Soil Profile 83-93 1.6 Soil Erosion and Runoff Status 94 1.7 Land Use Pattern 95-139 Chapter II: District Water Profile: 2.1 Area Wise, Crop Wise irrigation Status 140-150 2.2 Production and Productivity of Major Crops 151-158 2.3 Irrigation based classification: gross irrigated area, net irrigated area, area under protective 159-160 irrigation, un irrigated or totally rain fed area Chapter III: Water Availability: 3.1: Status of Water Availability 161-163 3.2: Status of Ground Water Availability 164-169 3.3: Status of Command Area 170-194 3.4: Existing Type of Irrigation 195-198 Chapter IV: Water Requirement /Demand 4.1: Domestic Water Demand 199-200 4.2: Crop Water Demand 201-210 4.3: Livestock Water Demand 211-212 4.4: Industrial Water Demand 213-215 4.5: Water Demand for Power Generation 216 4.6: Total Water Demand of the District for Various sectors 217-218 4.7: Water Budget 219-220 Chapter V: Strategic Action Plan for Irrigation in District under PMKSY 221-338 List of Tables Table 1.1: District Profile Table 1.2: Demography Table 1.3: Biomass and Live stocks Table 1.4: Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography Table 1.5: Soil Profile Table 1.7: Land Use Pattern Table -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch ISSN: 2249-894X Impact Factor : 5.2331(UIF) Volume - 7 | Issue - 6 | March - 2018 ____________________________________________ THE GLORY THAT WAS CHITTAPUR IN KALBURGI DISTRICT Tea cher Education - Yesterday & Today Rajeshwari U. Ramteerth ABSTRACT : The District of Gulbarga is rich in ancient cultural traditions as also in historical associations with its ancient capital historic battle fields of architectural monuments it attracts the attention of any enlightened visitors & takes him back to those days of the glorious past when kingdoms after kingdoms more reigned & declined over this ancient land. KEYWORDS : ancient cultural traditions , historical associations. INTRODUCTION : For nearly fifteen hundred years or more the district of Gulbarga had its influence on the historical & cultural life of the Deccan plateau several of the important ruling dynasties of the Deccan had their capital in this district. The capital of the Rastrakutas was Malkhed which is 22 miles from Gulbarga towards the last in the same manner Kalyana the capital city of the later Chalukyas&Kalchuris formed part of the Gulbarga district. Gulbarga city was selected as capital by alludinBahman shah. It remained the seat of the Bahamani govt. from 1347 to 1424 A.D. when during the reign of Ahamad Shah wali (1424-1436) the capital was shifted to Bidar. The Bahmani sultan during this period ruled over the Deccan plateau from the to river Krishna to river Tapati& from the western Ghats to the Telanganaarea. These facts therefore, have naturally left their indelible impression on the history & cultural of three parts. LOCATION :- Chittapurtaluka which is 50 miles from Gulbarga District it liesbetween 76.52 & 77.12 northern longitude and 16.5 to 17.29 eastern latitude is bounded on the north by the Gulbarga district of Karnataka state. -

Original Research Paper Dr. C.P.S. Hungund Statistics Ashwini S.R*

VOLUME - 10, ISSUE - 07, JULY- 2021 • PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8160 • DOI : 10.36106/gjra Original Research Paper Statistics ANALYSIS OF DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS AND KNOWLEDGE FACTORS ABOUT MENSTRUATION AMONG THE GIRLS STUDENTS OF DIFFERENT TALUKA OF KALBURGI DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE, INDIA Professor, Department of Statistics, Gulbarga University Kalaburagi- Dr. C.P.S. Hungund 585106, India. Research Scholar, Department of Statistics, Gulbarga University Ashwini S.R* Kalaburagi-585106,India. *Corresponding Author ABSTRACT This paper highlights the personal prole of the respondents belonging to different taluka of Kalburgi district with respect to knowledge, area and type of school. The test of association between demographic factors and knowledge factors about menstruation with respect to talukas of respondents were identied through chi-square test. The purpose of this study is to analyze the selected demographic factors and knowledge factors with respect to the students of different taluka. The Chi-Square test analyze that there is a signicant association between the demographic factors and knowledge factors with their respective taluka of the respondents. KEYWORDS : Demographic factors, Knowledge factors, Adolescent girl students, descriptive Statistics, chi-square test. 1. INTRODUCTION adolescents in rural areas were. In addition, religion, grade The present paper is aimed to analysis a scio demographic level, and living area also made the adolescents' health prole of high school going girl students of ve talukas viz: behavior signicantly different. As the result suggested, Aland, Gulbarga, Chitapur, Sedam, Jevargi of Kalaburgi gender, religion, grade level, and region need to be District, Karnataka state. The test of association between considered when designing health promotion interventions selected demographic factors, knowledge factors about among Korean adolescents. -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume: 04, Issue: 04 "April 2019" CRAFTSMEN AND SOME POLITICAL AND RELIGIOUS ASPECTS IN THE GOA REGION (AD 1000 TO 1510) Christopher H. De Souza Ph. D Student, Department of History, Goa University ABSTRACT The craftsmen played an important role for the rulers and elites. They were involved in the minting of coins as well as during the time of making donations. They also produced items which were utilised by the elites as well as the common people. Besides this, they were also involved in various temple celebrations and activities. They also made various grants for the upkeep of the temples. This article attempts to study the contributions of the craftsmen in the political and religious domain. Keywords: Craftsmen, artisans, goldsmiths, inscriptions INTRODUCTION The craftsmen played an important role for the state and the elites. They were required at the time of donations and giving of gifts. They were also involved in donations to temples. V. R. Mitragotri has briefly mentioned about the craftsmen and their role in the society of Goa. G. M. Moraes has touched upon some aspects of guild activity. V. V. Mirashi, R. N. Gurav and S. L. Shantakumari have provided important details as well as inscriptions wherein the craftsmen and artisans have been mentioned. These inscriptions help gain an insight into the actions of the rulers and elites as well as the temples and how the craftsmen interacted to play a role in the political and religious sphere. Some of the inscriptions which show the role that the craftsmen played in the political and religious landscape will be seen. -

Report, Which, with the Suggestions and Inputs of the Members of the Technical Committee of KEA and the Internal Assessor of KEA, Was Modified

PREFACE Karnataka is a State that has a long and diverse history exhibiting itself in the historic caves, forts, places of worship and palaces and through arts and artifacts preserved in museums. If history is to be conserved for the generations to come; historic places, monuments and museums need to be conserved. The conservation of historic structures and sites is guided by the tenet of minimum intervention and retention of original fabric, so that no information that it provides to the viewer/academician is lost. Funds provided under the 12th Finance Commission were utilized by the Department of Archeology, Museums and Heritage of the Government of Karnataka to conserve historic structures, sites and museums in Karnataka. An evaluation of this work was entrusted by the Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department of Government of Karnataka to Karnataka Evaluation Authority (KEA). The KEA outsourced this study to READI-INDIA, Dharwad. They completed the evaluation and presented their report, which, with the suggestions and inputs of the members of the Technical Committee of KEA and the Internal Assessor of KEA, was modified. The final report is before the reader. The most satisfying finding of the evaluation study has been that the work of conservation of historic monuments and sites has been done in an appropriate manner (least intervention) by the department. In the course of the study, from the findings and recommendations the following main points have emerged- (i) The declaration of any building as “heritage buildi ng” should be done by the Department of Archeology, Museums and Heritage and not by the local authority under the Karnataka Town and Country Planning Act, 1961. -

A Study of Buddhist Sites in Karnataka

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicjournal.in Volume 3; Issue 6; November 2018; Page No. 215-218 A study of Buddhist sites in Karnataka Dr. B Suresha Associate Professor, Department of History, Govt. Arts College (Autonomous), Chitradurga, Karnataka, India Abstract Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha wandered the country side teaching what he had learned. He organized a community of monks known as the ‘Sangha’ to continue his teachings ofter his death. They preached the world, known as the Dharma. Keywords: Buddhism, meditation, Aihole, Badami, Banavasi, Brahmagiri, Chandravalli, dermal, Haigunda, Hampi, kanaginahally, Rajaghatta, Sannati, Karnataka Introduction of Ashoka, mauryanemperor (273 to 232 B.C.) it gained royal Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the support and began to spread more widely reaching Karnataka history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was and most of the Indian subcontinent also. Ashokan edicts founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of which are discovered in Karnataka delineating the basic tents Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got of Buddhism constitute the first written evidence about the enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha presence of the Buddhism in Karnataka. -

In the High Court of Karnataka Circuit Bench at Gulbarga Dated This the 20Th Day of April 2012 Present the Hon'ble Mr.Justice

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA CIRCUIT BENCH AT GULBARGA DATED THIS THE 20TH DAY OF APRIL 2012 PRESENT THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE H.BILLAPPA AND THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE V.SURI APPA RAO WPHC NO.704 OF 2012 Between: Moulali S/o Nabisab Age:27 years Occ:Business R/o At Deval Ganagapur, Tq. Afzalpur Dist. Gulbarga. Petitioner (By Sri Sanjay Bannur, and Vinay Kolda, Advocates, Sri Avinash A Uploankar, Advocates) And: 1. The State of Karnataka Superintendent of Police Gulbarga-585 101. 2. The Deval Gangapur Police Station Tq. Afzalpur Dist. Gulbarga-585101. 3. Bheemashankar 7 S/o Dhamuniyappa Age:45 years Occ:Business R/o At Deval Ganagapur Tq. Afzalpur Dist. Gulbarga-585 101. 4. Kasturibai W/o Bheemashankar Age:35 years, Occ:Housewife R/o At Deval Ganagapur Tq. Afzalpur Dist. Gulbarga-585 101. Respondents (By Smt. Anuradha M.Desai, Addi. SPP for Ri and R2) This WPHC is filed under Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution of India praying to issue a writ of Habeas Corpus directing respondents 1 to 4 to immediately produce Roopa daughter of the respondents 3 and 4, before this Hon’ble Court. This WPHC coming on for Preliminary Hearing this day, H.BILLAPPA J., made the following: ORDER The girl Roopa is produced before the Court by the PSI Deval Ganagapura police Station. The girl states that she is a Graduate and she is aged about 23 years. She is not willing to marry the petitioner. The marriage between her and the 3 petitioner is not yet registered. -

Bidar District “Disaster Management Plan 2015-16” ©Ãzàgà F¯Áè

BIDAR DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2015-16 Government of Karnataka Bidar District “Disaster Management Plan 2015-16” ©ÃzÀgÀ f¯Áè “““«¥ÀvÀÄÛ“«¥ÀvÀÄÛ ¤ªÀðºÀuÁ AiÉÆÃd£É 20152015----16161616”””” fĒÁè¢üPÁjUÀ¼À PÁAiÀiÁð®AiÀÄ ©ÃzÀgÀ fĒÉè BIDAR DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OFFICE, BIDAR. BIDAR DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2015-16 CONTENTS SL NO TOPIC PAGE NO 1 Preface 03 2 Glossary 04 3 Chapter-1 :Introduction 05-13 4 Chapter-2 : Bidar District Profile 14-25 5 Chapter-3 : Hazard Risk Vulnerability and Capacity (HRVC) 26-41 Analyses 6 Chapter-4 : Institution Mechanism 42-57 7 Chapter-5: Mitigation Plan 58-73 8 Chapter-6: Response Plan 74-80 9 Chapter-7: Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 81-96 10 Chapter-8 : Resources and Contact Numbers 97-117 11 Chapter-9 : Standard Operating Processor (SOPs) 118-125 12 Chapter-10 : Maps 126-137 13 Conclusion 138 14 Bibliography 139 BIDAR DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OFFICE, BIDAR. Bidar District Disaster Management Pla n 2015-16 Office of the Deputy Commissioner Bidar District, Bidar Shri. Anurag Tewari I. A.S Chairman of Disaster Management & Deputy Commissioner Phone: 08482-225409 (O), 225262(Fax) Bidar District E-mail: [email protected] PREFACE “Disaster” means unforeseen and serious threat to public life with suddenness in terms of time. Declaration of disaster depends on gravity or magnitude of situ ation, number of victims involved, time factor i.e. suddenness of an event, non- availability of medical care in terms of space, equipment’s medical and pa ramedical staff, medicines and other basic human needs like food, shelter and clothing, weather conditions in the locali ty of incident etc., thus enhancing human sufferings and create human needs that the victim cann ot alleviate without assistance. -

Historical Background and Distribution of Tourist Destinations in Kalaburgi Districts

Historical Background and Distribution of Tourist Destinations in Kalaburgi Districts Dr. Atik-ur-rahaman S.M. Principal, Paras MSW College, Jayanagar Cross, Sedam Road, Kalaburgi Introduction :- “History should be studied Arabic. The annual festival of Urs is celebrated at geographically and geography should be studied this dargah. historically”. The above definition rightly justifies the importance of both the fields. Because as it is Aiwane-Shahi building is situated within said, “if you know the geography then you can the premises of the dargah and is believed to be create history”. the residence of the Nizams. A circuit house that lies in the vicinity of the dargah, can also be visited Gulbarga District (Kalaburagi) :- Gulbarga district by tourists. is also Called Kalaburgi nad noted for its long history and its cultural heritage. There are many Sharana Basaveshwara Temple :- Sharana holy places are noticed in the district, noted for Basaveshwara Temple is located in the ancient their significant historical relevance. Many myths town of Kalburgi. This temple is believed to be and legends are associated with this holy district. devoted to the Hindu philosopher and religious Another interesting fact is that the district has teacher, Shri Sharana Basaveshwara. He was a 12th and 14th major rock Edicts (of Ashoka) that Lingayat saint and was known for Dasoha and were excavated by the Archaeologist at Sannati. Kayaka philosophy of ‘giving is earning’. Because of this discovery the name of the The temple has the samadhi of Sharana Gulbarga district occupies an important position in Basaveshwara, which is known as Garbha Gudi. the study of the early history. -

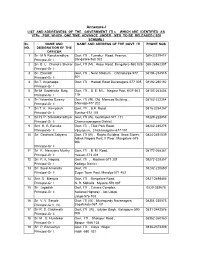

Annexure-I LIST and ADDRESSESS of the GOVERNMENT ITI S WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS Vtps for WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES to BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL

Annexure-I LIST AND ADDRESSESS OF THE GOVERNMENT ITI s WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS VTPs FOR WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES TO BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL. NAME AND NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE GOVT. ITI PHONE NOS NO. DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICER 1 Sri M N Renukaradhya Govt. ITI , Tumakur Road, Peenya, 080-23379417 Principal-Gr I Bangalore-560 022 2 Sri B. L. Chandra Shekar Govt. ITI (M) , Hosur Road, Bangalore-560 029 080-26562307 Principal-Gr I 3 Sri Ekanath Govt. ITI , Near Stadium , Chitradurga-577 08194-234515 Principal-Gr II 501 4 Sri T. Anjanappa Govt. ITI , Hadadi Road Davanagere-577 005 08192-260192 Principal-Gr I 5 Sri M Sadathulla Baig Govt. ITI , B. E. M.L. Nagara Post, KGF-563 08153-263404 Principal-Gr I 115 6 Sri Yekantha Swamy Govt. ITI (W), Old Momcos Building, , 08182-222254 Principal-Gr II Shimoga-577 202 7 Sri T. K. Kempaiah Govt. ITI , B.H. Road, 0816-2254257 Principal-Gr II Tumkur-572 101 8 Sri H. P. Srikanataradhya Govt. ITI (W), Gundlupet-571 111 08229-222853 Principal-Gr II Chamarajanagara District 9 Smt K. R. Renuka Govt. ITI , Tilak Park Road, 08262-235275 Principal-Gr II Vijayapura, Chickamagalur-577 101 10 Sri Giridhara Saliyana Govt. ITI (W) , Raghu Building Urwa Stores, 0824-2451539 Ashok Nagara Post, II Floor, Mangalore-575 006. Principal-Gr II 11 Sri K. Narayana Murthy Govt. ITI , B. M. Road, 08172-268361 Principal-Gr II Hassan-573 201 12 Sri P. K. Nagaraj Govt. ITI , Madikeri-571 201 08272-228357 Principal-Gr I Kodagu District 13 Sri Syed Amanulla Govt.